Northwestern Consolidated Milling Company

Northwestern Consolidated Milling Company was an American flour milling company that operated about one quarter of the mills in Minneapolis when the city was the flour milling capital of the world.[1] Formed as a business entity, Northwestern produced flour for the half century between 1891 and 1953, when its A Mill was converted to storage and light manufacturing.[2] At its founding, Northwestern was the city's and the world's second largest flour milling company after Pillsbury, with what is today General Mills a close third. The company was touched by an attempt at U.S. monopoly and became part of a Minneapolis oligopoly that valued in 1905 owned almost 9% of the country's flour and grist products.[2][3]

History

| Consolidation of Minneapolis Flour Mills[4] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Companies | Market Share |

| 1882 | 2 | 51% |

| 16 | about 49% | |

| 1890 | 4 | 87% |

| 1900 | 3 | 97% |

| 1891 Capacity in Barrels[5] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Company | Mills | Daily |

| Pillsbury-Washburn | 5 | 14,500 |

| Northwestern Consol. | 6 | 10,500 |

| Washburn-Crosby | 3 | 9,500 |

| Minneapolis Flour Mfg. Co. | 4 | 3,500 |

Technological advances in flour milling were already in place by the 1880s, when 18 different millers operated in Minneapolis. From that point on and for the next 50 years, mergers and changes in business administration were the primary developments in the industry.[2]

Northwestern and their new Ceresota[6] flour brand name were established in July 1891 by a group of businessmen led by former lumberman John Martin at six independent existing mills—the Crown Roller (2,500 barrels/day), Columbia (2,000), Northwestern (1,600), Pettit (1,600, to be an elevator), Galaxy (1,500) and Zenith (1,100). Martin became president, Joel B. Bassett was vice president, C. T. Fox was secretary and treasurer, and Fred C. Pillsbury, E. Zeidler and Albert C. Loring were the managers.[5] The company grew to nine mills and several elevator and storage facilities.[2] Loring's father Charles M. Loring was one of the directors.[5]

Northwestern's first decade was marked by financial instability because its founders paid too much for its properties and suffered from lack of capital. A reorganization followed in 1895 that somewhat alleviated the company's problems. In 1889-1990 the United States Milling Company formed at the Hecker-Jones-Jewell mills in New York City with the goal of becoming a flour monopoly by owning nearly all of the country's spring wheat mills. Northwestern, though, was the only company they acquired. Financially troubled, U.S. Milling in 1900 reorganized and became the Standard Milling Company with Northwestern as a subsidiary.[2]

By combining six mills, Northwestern's capacity was the second largest in the world at the time of its founding, after the giant Pillsbury-Washburn, and slightly more than Washburn, Crosby. By 1900, these three companies were an oligopoly holding 97% of the Minneapolis market.[2] In 1928 Washburn, Crosby became General Mills in a merger of U.S. millers and surpassed Pillsbury to become the world's largest flour milling company. In recent years General Mills acquired Pillsbury.[7]

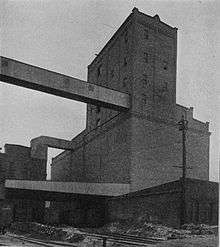

In January 1909, Northwestern opened its state of the art Elevator A, possibly the largest grain elevator ever built of brick. The elevator could hold 1,000,000 bushels of grain and its conveyors could each move 10,000 bushels per hour to the Crown Roller and Standard mills.[2] Along with Elevator B known as the Pettit Mill of which only the foundation remains, Elevator A is a contributing property of the Saint Anthony Falls History District listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1971.[8]

Today

After the center of U.S. flour milling moved to the east coast, the company's A and F Mills closed during the 1940s and 1950s. Of the 34 Minneapolis flour mills, only four are still standing on the Mississippi's west bank.[9] Of the four, the Crown Roller Mill and the Standard Mill were Northwestern mills (the A and F mills). Of concern to preservationists, Omni Investment had plans to build a condominium development on top of the remains of the Northwestern B mill and adjacent archaeological sites but the plan is stopped and is now in the court system.[10] Elevator A, now known as the Ceresota Building, and the Crown Roller Mill are in use today as office buildings. The Standard Mill became the Whitney Hotel but is closed. Ceresota is now a brand name of The Uhlmann Company and American Home Foods.[6]

Mills

| Northwestern Consol. Mills[11] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mill | Owners | Architect/Construction | Extant | Northwestern | Remains | Image |

| Crown Roller Mill | Charles Morgan Hardenbergh, John A. Christian, Llewellyn Christian, Charles Everett French | William F. Gunn | 1879- | A Mill | office building |  |

| Columbia Mill | Columbia Mill Company | 1882-1941 | B Mill aka Ceresota Mill | under Fuji-Ya, visible from Mississippi | ||

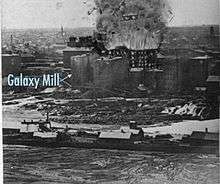

| Galaxy Mill | W.P. Ankeny, W. F. Cahill, Loren Fletcher, Charles M. Loring, Albert C. Loring[12] | 1874-1931 | C Mill | foundation visible, Mill Ruins Park |  | |

| Northwestern Mill | Siddle, Loren Fletcher and Holmes, John Martin[13] | 1879-1931 | D Mill | foundation visible, Mill Ruins Park | image | |

| Zenith Mill | Leonard Day and M.B. Rollins | 1871-1931 | E Mill | foundation visible, Mill Ruins Park | image | |

| Standard Mill | Ebenezer White and Dorilus Morrison, Whitney Hotel | Otis Arkwright Pray and William Dixon Gray | 1879- | F Mill | standing |  |

| Arctic/St. Anthony Mill | Perkins, Crocker, and Co., Hineline, Plenk and Wheeler | 1866-1919 | H Mill | foundation visible |  | |

| Elevator A | Northwestern | George T. Honstain, Fred W. Cooley | 1908- | Elevator A | office building |  |

| Pettit Mill | Pettit, Robinson, and Company | 1875-1931 | Elevator B | visible, Mill Ruins Park | image | |

| New City Waterworks | City of Minneapolis | 1883-ca.1931 | storage | foundation remains | ||

| Union Mill | Henry Gibson | 1863-ca. 1919/29 | storage | foundation visible |  | |

| Minneapolis Boiler Works | M.W. Glenn, unknown | ca. 1878 - 1985 | storage | foundation probably destroyed |  | |

| Phoenix Iron Works | D. Douglas and J.M. Schultz, Wilford and Northway | ca.1881-1985 | storage | foundation probably destroyed | ||

See also

Notes

- ↑ Mill City Museum. "History". Archived from the original on 2007-02-18. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Frame, Robert M. III, Jeffrey Hess (January 1990). "West Side Milling District" (PDF). U.S. National Park Service, Historic American Engineering Record MN-16. Retrieved 2016-10-17.

- ↑ Salisbury, Rollin D., Harlan Harland Barrows, Walter Sheldon Tower (1912). The Elements of Geography. University of Michigan, reprinted by H. Holt and company. p. 441.

- 1 2 3 Atwater, Isaac (1893). History of the City of Minneapolis, Minnesota. pp. 408, 630–631 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 American Home Foods / The Uhlmann Company (n.d.). "About Us". Retrieved 2007-04-14.

- ↑ "General Mills history of innovation" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-12-11. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ↑ "St. Anthony Falls Historic District". Minnesota Historical Society. 2001. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ↑ Hess, Demain, Jeffrey A. Hess (January 1990). "U.S. National Park Service, Historic American Engineering Record MN-12 p. 17". Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ↑ Bruch, Michelle (September 18, 2006). "Riding the Wave". Downtown Journal. and "Debate over the Wave condo project rolls on". February 2, 2007. and "Development roundup: Wave developers file lawsuit against Park Board". March 29, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ↑ Anfinson, Scott F. (1989). "Archaeology of the Central Minneapolis Riverfront, Part 1". The Minnesota Archaeologist 48 (1-2). Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ↑ Shutter, Marion Daniel (1923). History of Minneapolis, Gateway to the Northwest, via Rootsweb.com. The S J Clarke Publishing Co. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- ↑ Atwater, Isaac (1893). History of the City of Minneapolis, Minnesota via Google Books. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

Further reading

- Minneapolis Public Library (2001). "A History of Minneapolis: Milling". Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- Anfinson, Scott F. (1989). Archaeology of the Central Minneapolis Riverfront, Part 1 and Part 2. Retrieved on April 14, 2007.