Nude photography (art)

Fine art nude photography is a genre of fine-art photography which depicts the nude human body with an emphasis on form, composition, emotional content, and other aesthetic qualities. The nude has been a prominent subject of photography since its invention, and played an important role in establishing photography as a fine art medium. The distinction between fine art photography and other subgenres is not absolute, but there are certain defining characteristics. Erotic interest, although often present, is secondary,[1] which distinguishes art photography from both glamour photography, which focuses on showing the subject of the photograph in the most attractive way, and pornographic photography, which has the primary purpose of sexually arousing the viewer. Fine art photographs are also not taken to serve any journalistic, scientific, or other practical purpose. The distinction between these is not always clear, and photographers, as with other artists, tend to make their own case in characterizing their work,[2][3][4] though the viewer may have a different assessment.

The nude remains a controversial subject in all media, but more so with photography due to its inherent realism.[5] The male nude has been less common than the female, and more rarely exhibited or published.[6] The use of children as subjects in nude photography is especially controversial.

History

19th century

- Photography and the Traditional Arts

-

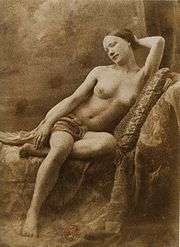

Photograph by Jean Louis Marie Eugène Durieu, Part of a series made with Eugène Delacroix

-

Odalisque (1857) by Eugène Delacroix (Oil on panel), a painting with similar pose

-

Gaudenzio Marconi made his living supplying académies to students at the École des beaux-arts in Paris

-

Adam and Eve by Frank Eugene, taken 1898, published in Camera Work no. 30, 1910

-

_-_Nudo_accademico.jpg)

Nude by Gaudenzio Marconi, 1841–1885

-

Guglielmo Plüschow Male nude

-

_-_n._1189_(other_version).jpg)

Wilhelm von Gloeden, Two male nudes outdoors c1900

Those early photographers in Western cultures who sought to establish photography as a fine art medium, frequently chose women as the subjects for their nude photographs, in poses that accorded with traditional nudes in other media. Before nude photography, art nudes usually used allusions to classical antiquity; gods and warriors, goddesses and nymphs. Depictions of male and female nudes in traditional art mediums had been mostly limited to portrayals as an ideal warrior or athlete (for men) or that emphasized divinity and reproduction (for women),[7] and early photographic art first engaged these archetypes as well. Poses, lighting, soft focus, vignetting and hand retouching were employed to create photographic images that rose to the level of art comparable to the other arts at that time.[5] The main limitation was that early photographs were monochrome. Although 19th century artists in other media often used photographs as substitutes for live models, the best of these photographs were also intended as works of art in their own right.

Nude photography was more controversial than painted nude works, and in order to avoid censorship some early nude photographs were described as "studies for artists",[5] while others were used as references by artists to do drawings and paintings as a supplement to live models. Eugène Delacroix was an early adopter of the practice of using photographs taken specifically for him by his friend, Eugène Durieu.[8] Edgar Degas made his own photographs that he used for painting references.[9]

Modern

- Modern photography

-

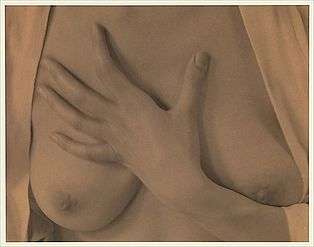

Georgia O’Keeffe, Hands and Breasts (1919) by Alfred Stieglitz

-

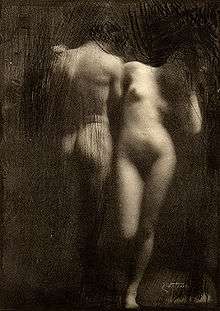

Nude study by Rudolf Koppitz (1927)

-

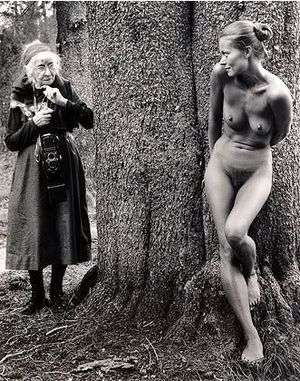

Imogen and Twinka, Photographed by Judy Dater (1974), it was the first adult full frontal nude photograph published in Life magazine

As fine art photography first embraced and then moved passed classical allegorical imagery, both male and female photographers began to use the male nude as another medium to examine issues of representation and identity, sexuality and voyeurism.[10] Photographing nudes (and particularly male nudes) became a way for women artists to engage the subject of “the nude” from the position of power traditionally reserved for male artists;[11] alternatively, nude self-portraiture allowed men to begin to re-evaluate accepted definitions of sensuality and masculinity by photographing themselves.[12]

Alfred Stieglitz is a major figure in bringing modern art to America by exhibiting the new genre of art in his New York galleries at the beginning of the 20th century. He is known to the public perhaps more for his relationship with Georgia O'Keeffe, whose nude photos he exhibited in 1921 while married to someone else.[13] "Stieglitz used the camera as a kind of mirror. 'My photographs,' he wrote in 1925, 'are ever born of an inner need--an Experience of Spirit. I do not make pictures . . . I have a vision of life and I try to find equivalents for it sometimes in the form of photographs.' Often he would write of true seeing and of inness. As O'Keeffe noted rightly, the man she knew so well was 'always photographing himself.'" [14]

Imogen Cunningham began taking photographs in Seattle in 1905, in the soft-focused pictorialist style popular at that time; but is best known for the sharp-focused modern style she developed later. She is also attributed as the first woman photographer to take a nude photo of a man (her husband, Roi Partridge).[15] In the work of Judy Dater, one particular photo, Imogen and Twinka, became one of the most recognizable images caught by an American photographer. It features a 91 year old Imogen Cunningham and a nude Twinka Thiebaud.[16] The photo was the first adult full frontal nude photograph published in Life magazine, in 1976.[17]

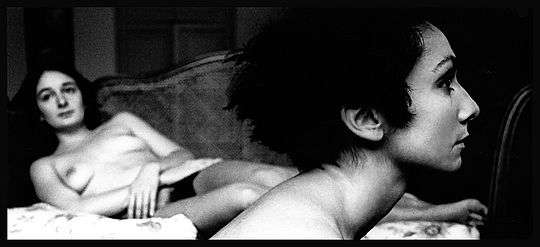

After World War I, avant-garde photographers became more experimental in their portrayal of nudity, using reflective distortions and printing techniques to create abstractions or depicting real life rather than classical allusions.

Beginning in the late 1920s Man Ray experimented with the Sabattier, or solarization process, a technique that won him critical esteem, especially from the Surrealists. Many of the central figures of Surrealism—Breton, Magritte, Dalí—followed his example in using photography in addition to other media. Other photographers, such as Maurice Tabard and Raoul Ubac, were directly inspired by Man Ray’s techniques, while photographers such as André Kertész and Brassaï were indirectly influenced by his innovative approach to the medium.

Edward Weston evolved a particularly American aesthetic, using a large format camera to capture images of nature and landscapes as well as nudes, establishing photography as a fine arts medium.[18] In 1937 Weston became the first photographer to be awarded a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellowship.[19] For a famous example of Weston's work see: Charis Wilson.[20]

Bill Brandt is best known for a series of nudes developed primarily between 1945 and 1961, that are both personal and universal, sensual and strange, collectively exemplifying the “sense of wonder” that is paramount in his photographs. Brandt’s work is unpredictable not only in the range of his subjects but also in his printing style, which varied widely throughout his career. This exhibition is the first to emphasize the beauty of Brandt’s finest prints, and to trace the arc of their evolution.[21]

Many fine art photographers have a variety of subjects in their work, the nude being one. Diane Arbus was attracted to unusual people in unusual settings, including a nudist camp. Lee Friedlander had more conventional subjects, one being Madonna as a young model.[22]

Contemporary

- Contemporary photography

-

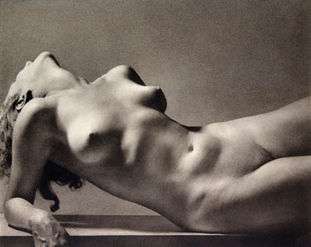

Nudes (1980) by Augusto De Luca

The distinction between fine art and glamour is often one of marketing, with fine art being sold through galleries or dealers in limited editions signed by the artist, and glamour photos being distributed through mass media. For some, the difference is in the gaze of the model, with glamour models looking into the camera, while art models do not.[23]

Glamour and fashion photographers have aspired to fine art status in some of their work. One of the first was Irving Penn, who progressed from Vogue magazine to photographing fashion models such as Kate Moss nude. Richard Avedon, Helmut Newton and Annie Leibovitz[24] have followed a similar path with portraits of the famous, many of them nude.[25] or partially clothed.[26] In the post-modern era, where fame is often the subject of fine art,[27] Avedon's photo of Nastassja Kinski with a python, and Leibovitz's magazine covers of Demi Moore pregnant and in body paint, have become iconic. The work of Joyce Tenneson has gone the other way, from fine art with a unique, soft-focus style showing woman at all stages of life to portraiture of famous people and fashion photography.[28]

Although nude photographers have largely worked within established forms that show bodies as sculptural abstractions, some, such as Robert Mapplethorpe, have created works that deliberately blur the boundaries between erotica and art.

Several photographers have become controversial because of their nude photographs of underage subjects.[29] David Hamilton often used erotic themes,[30] but Jock Sturges celebrates the beauty of people in naturist settings without emphasis on sexuality.[31][32] Sally Mann was raised in rural Virginia, in a locale were skinny-dipping in a river was common, so many of her most famous photographs are of her own children swimming in the nude.[33] Less well-known photographers have been charged as criminals for photos of their own children.[34]

Body image has become a topic explored by many photographers working with models whose bodies do not conform to conventional prejudices about beauty.[35]

Issues

Public perception

At the beginning of the 21st century, it has become difficult to make an artistic statement in nude photography, given the proliferation of non-artistic and pornographic images which taints the subject in the perception of most viewers, limiting the opportunities to exhibit or publish the images. When they appear in mainstream consumer magazines such as Popular Photography, PC Photo, and Shutterbug; the editors receive sufficient negative response that they tend to reject the work of serious nude-image photographers.[36]

Children as subjects

Several photographers have become controversial because of their nude photographs of underage subjects.[29] David Hamilton often used erotic themes in books such as The Age of Innocence,[37] which have caused controversy in both the US and the UK. Jock Sturges celebrates the beauty of people in naturist settings[31][32] and states that his work is not exploitative; however in 1990 the FBI raided his studio and made charges that were later dismissed.[38][39] However, due to the local nature of US laws on the issue, books of both Hamilton's and Sturges' photos have been ruled obscene in the states of Alabama, South Carolina, and Colorado.[40]

Sally Mann was raised in rural Virginia, in a locale where skinny-dipping in a river was common, so many of her most famous photographs are of her own children swimming in the nude.[41] Less well-known photographers have been charged as criminals for photos of their own children.[34] Some writers characterize many of these images as sexualizing children regardless of artistic merit.[42]

Body image

Body image has become a topic explored by many photographers working with models who do not conform to conventional ideas about beauty. Leonard Nimoy, after many years photographing conventionally beautiful professional models, realized that he was not capturing individual personalities, so he created a series with women interested in "Fat Liberation".[35] Sally Mann's more recent nudes have been of her husband, whose body shows the effects of muscular dystrophy.[43]

Erotic art

Many contemporary artists push the boundaries by having work with both aesthetic qualities and explicit sexuality. Late in his life Robert Mapplethorpe created work that was controversial in part by being on display in Washington, DC in a gallery receiving public funds.[44] When a Robert Mapplethorpe retrospective opened at the Cincinnati Contemporary Arts Center in 1990, Dennis Barrie became the first American museum director to be criminally prosecuted for the contents of an exhibition. Charged with "pandering obscenity" and showing minors in a state of nudity, a jury acquitted Barrie and the Arts Center of all charges.[45]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Clark, Kenneth (1956). "1. The Naked and the Nude". The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01788-3.

- ↑ Rosenthal,Karin. "About My Work". Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- ↑ Schiesser, Jody. "Silverbeauty - Artist Statement". Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- ↑ Mok, Marcus. "Artist's Statement". Retrieved 2012-11-12.

- 1 2 3 "Naked before the Camera". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ Weiermair, Peter & Nielander, Claus. Hidden Image: Photographs of the Male Nude in the 19th and 20th Centuries. MIT Press, 1988. ISBN 0262231379.

- ↑ "Sorabella, Jean. January 2008. The nude in western art and its beginnings in antiquity. In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–.".

- ↑ Van Deren Coke (Spring 1962). "Two Delacroix Drawings Made from Photographs". Art Journal. College Art Association. 21 (3): 172–174. doi:10.2307/774417. JSTOR 774417.

- ↑ "After the Bath, Woman Drying Her Back". The J. Paul Getty Museum. Retrieved 2013-05-18.

- ↑ Weiermair, Peter (Ed.). (1994). The male nude: A male view: An anthology. Zurich: Edition Stemmle.

- ↑ Weiermair, Peter (Ed.). (1995). Male nudes by women: An anthology. Zurich: Edition Stemmle.

- ↑ Massengill, Reed. (2005). Self-exposure : the male nude self portrait. New York: Universe.

- ↑ KIMMELMAN, MICHAEL (February 2, 2001). "ART REVIEW: Proselytizing for Modernism". The New York Times.

- ↑ Paul Richard (February 6, 1983). "Looking Back at the Seer of the New - Alfred Stieglitz: The Man, The Battle, The Art". The Washington Post.

- ↑ CHARLES HAGEN (13 Oct 1995). "Sampling Imogen Cunningham's Vibrant Diversity". New York Times. p. C27.

- ↑ Fallis, Greg. Judy Dater, Sunday Salon with Greg Fallis, UTATA.org

- ↑ Life magazine, Bicentennial Special Issue (1976) called: Remarkable American Women 1776-1976.

- ↑ "Edward Weston". University of Arizona, Center for Creative Photography. Retrieved 2013-05-18.

- ↑ "Edward Weston Photographs". Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona Libraries.

- ↑ Conger, Amy (2006). Edward Weston: The Form of Nude. Phaidon Press. ISBN 0714845736.

- ↑ "Bill Brandt: Shadow and Light". THe Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2013-05-18.

- ↑ "Nude photo of Madonna goes for $37,500". CNN. February 12, 2009.

- ↑ Conrad,Donna (2000), "A Conversation with Ruth Bernhard", Vol. 1 No. 3, PhotoVision

- ↑ "Exhibitions: Annie Leibovitz: A Photographer's Life, 1990–2005". The Brooklyn Museum. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ↑ Jones, Jonathan (2006-02-08). "Not naked but nude". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ↑ "Miley Knows Best". Vanity Fair. 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ↑ Needham, Alex (2012-02-22). "Andy Warhol's legacy lives on in the factory of fame". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ↑ "Joyce Tenneson". Retrieved 2013-05-18.

- 1 2 "Photo Flap". Reason. 1998. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ↑ Hamilton

- 1 2 Sturges, Jock & Phillips, Jayne Anne (1991). The Last Day of Summer. Aperture.

- 1 2 Sturges, Jock (1994). Radiant Identities: Photographs by Jock Sturges. Aperture. ISBN 0893815950.

- ↑ Mann, Sally and Price,Reynolds (1992). Immediate family. Aperture. ISBN 0893815233.

- 1 2 Powell, Lynn (2010). Framing Innocence: A Mother's Photographs, a Prosecutor's Zeal, and a Small Town's Response. The New Press. ISBN 1595585516.

- 1 2 "Leonard Nimoy: The Full Body Project". R.Michelson Galleries. Retrieved 11 November 2012.

- ↑ Deitcher, Kenneth (2008). "A Figure Study Workshop". PSA Journal. 74 (3): 36–37.

- ↑ Hamilton, David (1995). The Age of Innocence. Aurum Press. ISBN 1854103040.

- ↑ "Jock Sturges Biography".

- ↑ HAROLD MAASS (July 5, 1990). "Photo Lab Sets Off FBI Probe : Art: Jock Sturges' photographs of nude families are at issue". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ J.R. MOEHRINGER (March 8, 1998). "Child Porn Fight Focuses on 2 Photographers' Books". LA Times. Retrieved 2013-05-18.

- ↑ Mann, Sally and Price,Reynolds (1992). Immediate Family. Aperture. ISBN 0893815233.

- ↑ GORDON, MARY (1996). "Sexualizing Children: Thoughts on Sally Mann". Salmagundi. Skidmore College (111): 144–145. JSTOR 40535995.

- ↑ Kuspit, Donald (Jan 2010). "Sally Mann at Gagosian Gallery". Artforum. 48 (5): 198–199.

- ↑ Bernays, Anne (Jan 20, 1993). "Art and the morality of the artist". The Chronicle of Higher Education. 39 (20): B1.

- ↑ "Exhibiting Controversy: From Mapplethorpe to "Body Worlds" and Beyond". University of Michigan. Retrieved 2013-05-18.

Further reading

- Benjamin, Louis (2009). The Naked and the Lens: A Guide to Nude Photography. Focal Press. ISBN 0240811593.

- Bertolotti, Alessandro, Books of nudes, Abrams, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8109-9444-7

- Booth, Alvin; Cotton, Charlotte, eds. (1999). Corpus: Beyond the Body. Edition Stemmle. ISBN 3908161940.

- Cooper, Emmanuel (1995). Fully Exposed: The Male Nude in Photography. Routledge. ISBN 0415032806.

- Cooper, Emmanuel (2004). Male Bodies: A Photographic History of the Nude. Pestel. ISBN 3791330543.

- Cunningham, Imogen and Lorenz, Richard (1998). Imogen Cunningham: On the Body. Bullfinch Press. ISBN 0821224387.

- Davis, Melody D. (1991). The Male Nude in Contemporary Photography. Temple University Press. ASIN B000M43NLC.

- Dawes, Richard, ed. (1984). John Hedgecoe's Nude Phtotgraphy. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- De Dienes, André (2005). Studies of the Female Nude. Twin Palms Publishers. ISBN 1931885443.

- Dennis, Kelly (2009). Art/Porn: A History of Seeing and Touching. Berg. ISBN 1847880673.

- Leddick, David (1997). Naked Men: Pioneering Male Nudes, 1935-1955. Universe. ISBN 0789300796.

- Leddick, David (2000). Naked Men Too: Liberating the Male Nude 1950-2000. Universe. ISBN 078930497X.

- Lewinski, Jorge (1987). The naked and the nude: a history of the nude in photographs, 1839 to the present. Harmony Books. ISBN 0517566834.