Octavian (romance)

Octavian is a 14th-century Middle English verse translation and abridgement of a mid-13th century Old French romance of the same name.[1] This Middle English version exists in three manuscript copies and in two separate compositions, one of which may have been written by the 14th-century poet Thomas Chestre who also composed Libeaus Desconus and Sir Launfal.[2] The other two copies are not by Chestre and preserve a version of the poem in regular twelve-line tail rhyme stanzas, a verse structure that was popular in the 14th century in England.[3] Both poetic compositions condense the Old French romance to about 1800 lines, a third of its original length, and relate “incidents and motifs common in legend, romance and chanson de geste.”[4] The story describes a trauma that unfolds in the household of Octavian, later the Roman Emperor Augustus, whose own mother deceives him into sending his wife and his two newborn sons into exile and likely death. After many adventures, the family are at last reunited and the guilty mother-in-law appropriately punished.[5][6]

Manuscripts

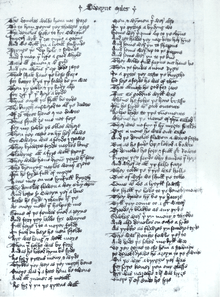

Copies of the Middle English version of Octavian are found in:[7]

- British Museum MS Cotton Caligula A.ii. (Southern Octavian, possibly by Thomas Chestre), mid-15th century.

- Lincoln Cathedral Library MS 91, the Lincoln Thornton Manuscript (Northern Octavian), mid-15th century.

- Cambridge University Library MS Ff. 2.38 (Northern Octavian), mid-15th century.

An incomplete printed copy by Wynkyn de Worde of the Northern Octavian, is found in Huntington Library 14615, early-16th century.

Two Middle English versions

There are two Middle English versions of this romance represented by these surviving manuscripts, both of which condense the plot of the Old French original to about a third of its length.[8] One of these is known from only one copy, British Museum MS Cotton Caligula A.ii, a manuscript copied sometime between 1446 and 1460[9] In this manuscript, Octavian precedes two Arthurian romances, Sir Launfal and Libeaus Desconus.[10] Sir Launfal is known only from this one manuscript and is signed with the name Thomas Chestre. On grounds of style, mode of composition and dialect it is believed that the two romances flanking Sir Launfal, including Octavian, may be by the same author.[11][12] This version of Octavian is known as the Southern Octavian.

The Southern Octavian is written in a Middle English dialect close to that of the southeast Midlands of England, as is Sir Launfal, although the problem of the direct borrowing of lines by Thomas Chestre in order to steal rhymes in other dialects, part of his “eclectic mode of composition”, is common to all three of these poems.[13] The verses of the Southern Octavian are of six lines, rhyming aaabab.[14]

The other version of this Middle English romance is found in two copies, Cambridge University Library MS Ff. 2.38, dating to about 1450 and Lincoln Cathedral Library MS 91, the Lincoln Thornton Manuscript, dated to about 1430–1440.[15] Of similar length and degree of condensation as the romance found in British Museum MS Cotton Caligula A. ii, this version differs in the structure of its verses and in the way the Old French story is made to unfold in “a more linear sequence.”[16] It is known as the Northern Octavian.

The verses of the Northern Octavian are of twelve lines each, following the more usual tail rhyme scheme found in other Middle English verse romances of the 14th century[17][18] “The dialect of the Lincoln Thornton text, copied by Robert Thornton of Yorkshire, is more northern than that of the Cambridge.”[19]

Plot summary

(This summary is based upon the copy of the Northern Octavian found in Lincoln Cathedral Library MS 91, the Thornton Manuscript.)

The Roman Emperor Octavian, upset that, after seven years of marriage, his wife has born him no child, weeps to himself in bed. Octavian's wife hears this and tries to comfort him with the suggestion that they build an abbey and dedicate it to the Virgin Mary. In thanks the Virgin will provide them with a child, she is sure (Octavian became the Roman Emperor Augustus in 27 BC, nearly thirty years before the birth of Christ. Geoffrey Chaucer also transports us back to the age of Augustus in his Book of the Duchess[20]).

Soon, the empress is pregnant with twins! When her time comes, she gives birth to two healthy boys. Octavian is delighted. His mother, however, tells him that the children are not his, a malicious lie that she tries to corroborate by bribing a male kitchen servant to enter the empress's bed while she is asleep. Octavian is taken to the room, sees the boy, kills him at once and holds his severed head in stark accusation before his terrified wife as she wakes from sleep.

On the day of an important Church service soon afterwards, Octavian's father-in-law is deceived into giving a verdict upon his daughter's alleged crime, not knowing that it is his own daughter whom he is passing judgement upon. She should be burned alive, with both her children, for doing such a thing, he insists. Octavian announces that this shall be done at once! They all gather outside the walls of Rome where huge branches are blackening in the flames. Her father cannot bear to attend. But at the last moment the emperor relents and banishes his wife and her two children into exile, instead.

Wandering alone in the forest, the empress (she is given no name in this romance) lies tired and exhausted at a spring one evening and falls asleep. In the morning, as the dawn chorus begins, an ape suddenly emerges from the forest and steals away one of her babies. Then a lioness appears and takes away the other in its mouth. The woman is distraught! She assumes that she is being punished for her sins and undertakes to journey to the Holy Land, so she travels to the Aegean Sea and takes a ship bound for Jerusalem. On the way, the crew stop at an island to take on fresh water and encounter a lioness suckling a human baby. The empress goes ashore and finds her own baby being treated by the lioness as her cub (a griffin – we already know – had snatched away the lioness shortly after it stole the child and took it to this island, where the lioness had killed it). The empress returns to the ship with her child and the lioness follows. They all arrive in Jerusalem where the King recognises the lady for who she is, names her little boy Octavian and allows her to stay, with her child and her lioness, in wealth and comfort.

The story now turns to the fate of the other child, the one who was taken by the ape, and it is this branch of the story that occupies the greater part of the romance. This child is soon rescued from the ape's clutches by a knight, who then loses the baby to a gang of outlaws who take the infant to the coast to sell. The baby is bought by a travelling merchant, Clement the villain (villain in a feudal sense, as a type of farmhand, not a moral sense; Clement, in fact, earns the listener's sympathy as the story unfolds). Clement does his best for the baby, finds it a wet-nurse, brings it back to his home in Paris and gives it to his wife. They rear the little boy as their own child, naming him Florent. As he grows up, however, Florent's noble blood manifests itself when he prefers to buy a falcon rather than two oxen. On another occasion he shows an inclination to be over-generous rather than drive a hard bargain and Clement despairs, leading to some comical scenes which culminate in Florent's insistence that he should borrow his father's rusty armour to go out to fight against a giant.

The Saracens have invaded France and are laying siege to Paris. The Saracen king has a giant to whom he has promised the hand of his beautiful daughter Marsabelle if he can bring to her the head of the French king, Dagobert. At this moment, the giant is leaning over the city wall of Paris, taunting the population and threatening to destroy them all. Everyone is terrified. Six knights have already sallied out and been slaughtered by this giant. Now he is leaning over the wall again and taunting them all once more.

Florent persuades his father to lend him the rusty armour, laughs as his parents fall over backwards when they try to pull the rusty sword from its scabbard, mounts his horse and rides to the outer wall where the waiting population burst out laughing in anxious derision and shout abuse. 'Here comes a mighty bachelor, magnificent in his saddle!' they cry. 'You can see by his shining armour that he is going to save us from this giant!'

- "Ilk a man sayde to his fere,

- 'Here commes a doghety bachelere,

- Hym semes full wele to ryde:

- Men may see by hys brene bryghte

- That he es a nobylle knyghte

- The geaunt for to habyde!'”[21]

Florent, of course, defeats the giant and immediately rides off to present the head to Marsabelle, explaining that the giant was unable to get the head of the King of France for her so he has brought his own instead! Then he tries to abduct her, but he is immediately set upon by all those in the castle, fights his way to safety and returns alone to Paris to a hero's welcome. Florent is knighted and the listener is treated to another comic scene as Clement worries that he might have to pay for the feast that the King of France and the Emperor of Rome have put on in Florent's honour. Yes, the Emperor of Rome, Florent's real father, has arrived in Paris to help life the siege.

The emperor is astounded at the noble bearing of this merchant's son and asks the boy if Clement is his real father. Florent replies equivocally. Clement explains truthfully how he came by the child and the Emperor realises that Florent is his long-lost son. The next morning, Florent rides out to the pavilion of the Saracen king, provoking, by his confident boasts, a military engagement the very next day. He rides back to Paris to warn everybody of the impending battle. The next day the forces engage and the fighting is long and hard. Sir Florent performs magnificently, wearing Marsabelle's sleeve on his lance, and saves the Christian forces from defeat. As night falls and the armies fall back, Florent rides to where Marsabelle is staying, where she vows to marry him and become a Christian, and warns him about her father's invincible horse.

Early the next morning, Clement earns his own moment of glory when he rides into the Saracen camp and, through a brave deception, comes away with this horse to give to his son Florent. Florent, however, in keeping with his true nobility, asks Clement to give it instead to the Emperor of Rome as a gift from himself.

Later that day, battle resumes and Florent brings Marsabelle into Paris by boat. However, things go badly for the Christian army during Florent's absence and it is defeated. They are all led away captive, including Florent, the Emperor of Rome and King Dagobert of France. Suddenly and unexpectedly, however, another Christian army arrives, raised by the King of Jerusalem and headed by Florent's brother Octavian. It vanquishes the Saracen host and when the fighting is over they all retire to a nearby castle where Octavian reveals his true identity to the Emperor of Rome and presents his mother to him. Then the lady notices Florent and recognises him as her own son. “Then was thore full mekill gamen, with halsynge and with kyssyngez samen”[22] Then there was hugging and kissing!

Florent and Marsabelle are married and return to Rome. The emperor explains what was told to him on that fateful day so long ago, and his mother is sentenced to be burned to death in a brass tub, but conveniently, she takes her own life instead. And so ends the story of Octavian.

Sources and analogues

Octavian has similarities with the Middle English Breton lays and is imbued, like much of medieval romance, with the characteristics of folktale and myth.[23] It is also a family romance, and “nurture is a particularly important theme in Octavian's treatment of the family.”[24] But like many other Middle English verse romances, its displays a flexible style during the course of its story,[25] beginning in this case as a tale of suffering and endurance in a similar vein to the 12th-century Latin “Constance saga” from which the 14th century Middle English tale of Emaré and Geoffrey Chaucer's story of Constance derive,[26] but ending in the more heroic vein of a chanson de geste.[27] The middle of the romance is almost a burlesque comedy between Florent and his father Clement who, “obsessed with merchandise, is the great comic character of the romance, and he fights a long and losing battle against the boy's inability to extract the smallest financial advantage from any commercial transaction entrusted to him."[28] It is not common for the mercantile classes to be given a major role in medieval romance and “its treatment of social class distinguishes Octavian from other similar Middle English romances.”[29]

The tale of Octavian uses a number of story elements found in other Middle English verse romances of the 14th century.

Queen falsely accused

The opening sequences of many Middle English romances feature a queen or princess or other noble lady who has been unjustly accused of a crime and who narrowly escapes death by being sent into exile, often known as the “calumniated queen”.[30] Octavian's queen is snatched away from execution at the last minute and sent into exile.[31] Geoffrey Chaucer's heroine Constance, in his Canterbury Tale from the Man of Law, is married to a heathen king and then bundled into a small boat and set adrift on the orders of her mother-in-law, when all about her have been brutally murdered.[32] Emaré, daughter of the Emperor of Germany, is bundled into a similar boat following her father's vow to kill her.[33] Crescentia is accused by her brother-in-law of infidelity.[34]

Cristobel, daughter of the Earl of Artois, in a 14th-century English verse romance Sir Eglamour of Artois, is bundled into a boat and set adrift, following the birth of her illegitimate son.[35] Margaret, wife of the king of Aragon in a 14th-century English verse romance Sir Tryamour, is sent into exile, which is intended by the evil steward of her husband's kingdom to end swiftly in death.[36] The wife of Sir Isumbras is captured by a Saracen king in a popular early-14th-century Middle English verse romance Sir Isumbras and sent to live in his land.[37] The daughter of the Emperor of Rome in the early-13th-century Old French romance William of Palerne sends herself into exile and is hunted mercilessly following an elopement with her lover William, during which adventure they don bearskins and are protected by a werewolf.[38]

Significant involvement of animals

Octavian's two young sons are snatched away by a lion and an ape during their journey into exile with their mother.[39] Margaret in the verse romance Sir Tryamour has her cause aided by Sir Roger's intelligent dog.[40] Cristobel, in the English romance Sir Eglamour of Artois, has her baby son snatched away by a griffin and delivered stork-like to the King of Israel.[41] William and Emelior, in the mid-14th century Middle English version of William of Palerne, dress themselves in deerskins as another disguise, when the bearskins they are wearing have become a handicap to them.[42]

Sir Isumbras's three sons are snatched away by a lion, a leopard and a unicorn and with the departure of his wife as well, he is left all alone. But his children appear again at the end of this romance, riding the animals who stole them away.[43] The motif of the theft of young children by animals who do them no harm occurs in the legend of Saint Eustace, found in the Guilte Legende of the mid-13th century.[44] It occurs also in the 13th-century romance William of Palerne, or William and the Werewolf, when the young boy William is taken by a wolf who crosses the sea with him and cares for the child in its den.[45]

Sir Yvain, in Chrétien de Troyes' romance The Knight of the Lion, retold in the 14th century Middle English romance Yvain and Gawain,[46] adopts a lion halfway through the story, a lion that helps him subsequently to win a number of battles.[47]

Young man who does not know his origins

Florent is taken as a small baby and brought up as the son of a Paris merchant, knowing nothing of his true heritage.[48] In the Middle English Breton Lay Sir Degaré, the eponymous hero is taken as a baby to the door of a hermitage and brought up by the hermit's sister and her husband, knowing nothing of his royal mother.[49]

Cristobel's little boy in the romance Sir Eglamour of Artois is similarly delivered into a new family at the very start of his life and only knows his real mother when, like Sir Degaré, he wins her hand in marriage in a tournament near the end of the tale.[50][51] Neither Perceval, in the Middle English Arthurian romance Sir Perceval of Galles, nor the Fair Unknown in Thomas Chestre's Lybeaus Desconus, has any idea who his father is when he arrives at King Arthur's court.[52][53]

Giants

Giants abound in Middle English romance. Octavian defeats the Saracen giant who is menacing Paris.[54] Sir Eglamour of Artois fights with one in a forest far to the west.[55] The Fair Unknown kills three.[56] King Arthur kills one on his journey to meet the Roman army in battle in the Alliterative Morte Arthure,[57] as does Sir Yvain in the Middle English Yvain and Gawain[58] and Perceval in the Middle English Sir Perceval of Galles.[59]

Unawareness of relatives

Following the battle with the giant, Florent speaks with the Emperor of Rome who, in the original Old French romance and in the Southern Octavian, despite feelings of natural affinity for the boy, does not learn who his son is until the very end of the romance.[60] Sir Degaré jousts for his mother's hand in marriage, unaware of who she is.[61] Sir Tryamour jousts with his real father in a tournament, neither of them knowing who the other is.[62] Sir Eglamour jousts with his son who does not recognise him.[63]

Fighting to rescue a maiden

Sir Florent performs great feats of heroism in order to woo and finally to seize Marsabelle from the clutches of her father, the Saracen king.[64] Tryamour concludes his romance with a series of battles to rescue a maiden.[65] Ipomadon proves himself endlessly in battle and tournament before rescuing his true love from the clutches of his rival at the very end of the romance Ipomadon.[66] The Fair Unknown travels on a quest to rescue a damsel in distress in Thomas Chestre's Libeaus Desconus.[67]

Heritage rediscovered

At the end of this romance Octavian, Florent is reunited with his mother and brother and recognises that the Emperor of Rome is his father.[68] Likewise, Sir Degaré is reunited with his mother and his father,[69] Sir Tryamour with his father,[70] Sir Eglamour of Artois with his true love Cristobel[71] and Sir Isumbras with his entire family.[72] Unlike the Greek tragedies Oedipus the King and Ion, whose plots also involve a young man brought up without any knowledge of his true origins, these Medieval romances are at heart comedies. All turns out well in the end.

Notes

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Four Middle English Romances. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Western Michigan University for TEAMS.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (Ed). 1969. Lybeaus Desconus. Oxford University Press for the Early English Text Society.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (Ed). 1972. Six Middle English Romances. Everyman's Library.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (Ed). 1972.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (Ed). 1969.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (Ed). 1969.

- ↑ Lupack, Alan. 2005. Oxford Guide to Arthurian Literature and Legend. Oxford University Press, p 320.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (Ed). 1969. pp 34–35.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Octavian: Introduction.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Octavian: Introduction.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (Ed). 1972.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Octavian: Introduction.

- ↑ eChaucer – texts: http://www.umm.maine.edu/faculty/necastro/chaucer/texts/bd/bd07.txt line 368.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Octavian, lines 983–994.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Octavian, lines 1795–1796.

- ↑ Brewer, Derek. 1983. History of Literature Series: English Gothic Literature. Schocken Books, New York, pp 81–82.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Octavian: Introduction.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (Ed). 1972, p i.

- ↑ Laskaya, Anne and Salisbury, Eve (Eds). 1995. The Middle English Breton Lays. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Western Michigan University for TEAMS.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (Ed). 1972. pp i, xv.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (Ed). 1972. p xvi.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Octavian: Introduction.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet. (Ed) 1996.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Octavian, http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/octavfrm.htm lines 256–279.

- ↑ eChaucer – texts: http://www.umm.maine.edu/faculty/necastro/chaucer/texts/ct/06mlt07.txt lines 428–448.

- ↑ Laskaya, Anne and Salisbury, Eve (Eds). 1995. Emaré http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/emare.htm lines 265–280.

- ↑ "OCTAVIAN: NOTES"

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Sir Eglamour of Artois, http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/eglafrm.htm lines 778–810.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Sir Tryamour http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/tryafrm.htm lines 199–222.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Sir Isumbras http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/isumfrm.htm lines 304–339.

- ↑ Skeat, Walter W (Ed). 1867, reprinted 1996. The Romance of William of Palerne. Boydell and Brewer Limited, for the Early English Text Society.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Octavian, lines 328–345.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Sir Tryamour, lines 565–576.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Sir Eglamour of Artois, lines 808–831.

- ↑ Skeat, Walter W (Ed). 1867, reprinted 1996. The Romance of William of Palerne, lines 2568–2596.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Sir Isumbras lines 724–735.

- ↑ Hamer, Richard. 2007 (Ed). Guilte Legende Oxford University Press for the Early English Text Society. 153. Saint Eustace, pp 789–798.

- ↑ Skeat, Walter W (Ed). 1867, reprinted 1996. The Romance of William of Palerne, p 6.

- ↑ Braswell, Mary Flowers. 1995.

- ↑ Kibler, William W., and Carroll, Carleton W., 1991. Chrétien de Troyes: Arthurian Romances. Translated from Old French with an introduction. Penguin Books Limited.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Octavian, lines 592–615.

- ↑ Laskaya, Anne and Salisbury, Eve (Eds). 1995. Sir Degaré lines 247–270.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Sir Eglamour of Artois, lines 1093–1119.

- ↑ Laskaya, Anne and Salisbury, Eve (Eds). 1995. Sir Degaré lines 575–592.

- ↑ Braswell, Mary Flowers. 1995 (Ed). Sir Perceval of Galles and Yvain and Gawain. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Western Michigan University for TEAMS. Sir Perceval of Galles, http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/percfrm.htm lines 497–512.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (Ed). 1969. Lybeaus Desconus. Oxford University Press for the Early English Text Society. Lambeth Palace MS 306, lines 49–72.

- ↑ Hudson. Harriet (Ed). 1996. Octavian lines 1016–1039.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Sir Eglamour of Artois, lines 283–333.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (Ed). 1969.

- ↑ Benson, Larry D, revised Foster, Edward E (Eds). 1994. King Arthur's Death: the Middle English Stanzaic Morte Arthur and Alliterative Morte Arthure. Kalamazoo, Michigan: Western Michigan University for TEAMS. http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/alstint.htm Alliterative Morte Arthure, lines 840–1224.

- ↑ Braswell, Mary Flowers (Ed). 1995. Yvain and Gawain, lines 2429–2485.

- ↑ Braswell, Mary Flowers (Ed). 1995. Sir Perceval of Galles, lines 2005–2099.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Octavian: Introduction.

- ↑ Laskaya, Anne and Salisbury, Eve (Eds). 1995. Sir Degaré lines 510–575.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Sir Tryamour, lines 775–783.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Sir Eglamour of Artois, lines 1174–1239.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Octavian, lines 1050–1638.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Sir Tryamour,

- ↑ Purdie, Rhiannon (Ed). 2001. Ipomadon. Oxford University Press for the Early English Text Society. 366 pp.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (Ed). 1969.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Octavian, lines 1770–1800.

- ↑ Laskaya, Anne and Salisbury, Eve (Eds). 1995. Sir Degaré, lines 1045–1085.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Sir Tryamour. lines 1138–1161.

- ↑ Hudson, Harriet (Ed). 1996. Sir Eglamour of Artois. lines 1240–1257.

- ↑ Mills, Maldwyn (Ed). 1972. Sir Isumbras. lines 757–774.