Old Burmese

| Old Burmese | |

|---|---|

|

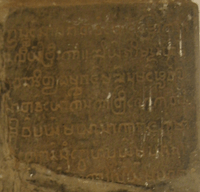

Detail of the Myazedi inscription | |

| Region | Pagan |

| Era | 12th–16th centuries |

|

Sino-Tibetan

| |

| Burmese script | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 |

obr |

Linguist list |

obr |

| Glottolog |

oldb1235[1] |

Old Burmese was an early form of the Burmese language, as attested in the stone inscriptions of Pagan, and is the oldest phase of Burmese linguistic history. The transition to Middle Burmese occurred in the 16th century.[2] The transition to Middle Burmese included phonological changes (e.g. mergers of sound pairs that were distinct in Old Burmese) as well as accompanying changes in the underlying orthography.[2] Word order, grammatical structure and vocabulary have remained markedly comparable, well into Modern Burmese, with the exception of lexical content (e.g. function words).[2][3]

Phonology

Unlike most Tibeto-Burman languages, Burmese has a phonological system with two-way aspiration: preaspiration (e.g. မှ hma. vs. မ ma.) and postaspiration (e.g. ခ kha. vs. က ka.).[4] In Burmese, this distinction serves to differentiate causative and non-causative verbs of Sino-Tibetan etymology.[4]

In Old Burmese, postaspiration can be reconstructed to the proto-Burmese language, whereas preaspiration is comparatively newer, having derived from proto-prefixes.[4] The merging of proto-prefixes (i.e., ဟ as an independent consonant used as a prefix) to preaspirated consonants was nearly complete by the 12th century.[4]

Orthography

Old Burmese maintains a number of distinctions which are no longer present in the orthography of standard Burmese.

Diacritics

Whereas Modern Standard Burmese uses 3 written medials (/-y-/, /-w-/, and /-r-/), Old Burmese had a fourth written medial /-l-/, which was typically written as a stacked consonant ္လ underneath the letter being modified.[3]

Old Burmese orthography treated the preaspirated consonant as a separate segment, since a special diacritic (ha hto, ှ) had not yet been innovated.[4] As such, the letter ha (ဟ) was stacked above the consonant being modified (e.g. ဟ္မ where Modern Burmese uses မှ).[4]

Gloss

Examples of such differences include the consonant yh- and the lateral clusters kl- and khl-. The earliest Old Burmese documents, in particular the Myazedi and Lokatheikpan inscriptions frequently have -o- where later Burmese has -wa.[5] Old Burmese also had a final -at and -an distinct from -ac and -any as shown by Nishi (1974).

| Old Burmese | Written Burmese |

|---|---|

| yh- | rh- |

| pl- | pr- |

| kl- | ky- |

| -uy | -we |

| -iy | -e |

| -o (early OB) | -wa |

Vocabulary

Aside from Pali, the Mon language had significant influence on Old Burmese orthography and vocabulary, as Old Burmese borrowed many lexical items (especially relating to handicrafts, administration, flora and fauna, navigation and architecture), although grammatical influence was minimal.[6] Many Mon loan words are present in Old Burmese inscriptions, including words that were absent in the Burmese vocabulary and those that substituted original Burmese words. Examples include:[6]

- "widow" - Mon ကၟဲာ > Burmese kamay

- "excrement" - Mon > Burmese haruk

- "sun" - Mon တ္ၚဲ > Burmese taŋuy

Moreover, Mon influenced Old Burmese orthography, particularly with regard to preference for certain spelling conventions:

- use of -E- (-ဧ-) instead of -Y- (ျ) (e.g. "destroy" ဖဧက်, not ဖျက် as in modern Burmese)[6]

- use of RH- (ဟြ > ရှ) instead of HR- as done with other preaspirated consonants (e.g. "monk" ရှင်, not ဟြင်)[6] - attributed to the fact that Old Mon did not have preaspirated consonants

Grammar

Two grammatical markers presently found in Modern Burmese are extant to Old Burmese:

- ၏ - finite predicate (placed at the end of a sentence)[6]

- ၍ - nonfinite predicate (conjunction that connects two clauses)[6]

In Old Burmese, ၍ was spelt ruy-e, following the pattern in Pali, whose inflected verbs can express the main predicate.[6]

Pali also had an influence in the construction of written Old Burmese verbal modifiers. Whereas in Modern Burmese, the verb + သော (sau:) construction can only modify the succeeding noun (e.g. ချစ်သောလူ, "man who loves") and သူ (su) can only modify the preceding verb (e.g. ချစ်သူ, "lover"), in Old Burmese, both constructions, verb + သော and verb + သူ were interchangeable.[6] This was a consequence of Pali grammar, which dictates that participles can be used in noun functions.[6]

Pali grammar also influenced negation in written Old Burmese, as many Old Burmese inscriptions adopt the Pali method of negation.[6] In Burmese, negation is accomplished by prefixing a negative particle မ (ma.) to the verb being negated. In Pali, အ (a.) is used instead.

Such grammatical influences from Pali on written Old Burmese had disappeared by the 15th century.[6]

Pronouns

| Pronoun | Old Burmese c. 12th century | Modern Burmese (informal form) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| I (first person) | ငါ | ငါ | |

| we (first person) | အတိုဝ့် | ငါတို့ or တို့ | Old Burmese တိုဝ့် was a plural marker, now Modern Burmese တို့. |

| you (second person) | နင် | နင် | |

| he/she (third person) | အယင် | သူ |

Surviving inscriptions

The earliest evidence of Burmese script (inscription at the Mahabodhi Temple in India) is dated to 1035, while an 18th-century recast stone inscription points to 984.[8] Perhaps the most well known inscription is the Old Burmese face of the Myazedi inscription. The most complete set of Old Burmese inscriptions, called She-haung Myanma Kyauksa Mya (ရှေးဟောင်း မြန်မာ ကျောက်စာများ; lit. "Ancient Stone Inscriptions of Myanmar") was published by Yangon University's Department of Archaeology in five volumes from 1972 to 1987.[9]

Notes

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Old Burmese". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- 1 2 3 Herbert, Patricia; Anthony Crothers Milner (1989). South-East Asia: Languages and Literatures: a Select Guide. University of Hawaii Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780824812676.

- 1 2 Wheatley, Julian (2013). "12. Burmese". In Randy J. LaPolla, Graham Thurgood. Sino-Tibetan Languages. Routledge. ISBN 9781135797171.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Yanson, Rudolf A. (2012). Nathan W. Hill, ed. Aspiration in the Burmese Phonological System: A Diachronic Account. Medieval Tibeto-Burman Languages IV. BRILL. pp. 17–29. ISBN 9789004232020.

- ↑ Hill, Nathan W. (2013). "Three notes on Laufer's law". Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. 36 (1): 57–72.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Uta Gärtner, Jens Lorenz, ed. (1994). "3". Tradition and Modernity in Myanmar. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 366–426. ISBN 9783825821869. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Bradley, David (Spring 1993). "Pronouns in Burmese-Lolo" (PDF). Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. Melbourne: La Trobe University. 16 (1).

- ↑ Aung-Thwin (2005): 167–178, 197–200

- ↑ Aung-Thwin 1996: 900

References

- Aung-Thwin, Michael A. (November 1996). "The Myth of the "Three Shan Brothers" and the Ava Period in Burmese History". The Journal of Asian Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 55 (4): 881–901. doi:10.2307/2646527.

- Aung-Thwin, Michael A. (2005). The Mists of Rāmañña: The Legend that was Lower Burma (illustrated ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2886-8.

- Dempsey, Jakob (2001). “Remarks on the vowel system of old Burmese.” Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 24.2: 205-34. Errata 26.1 183.

- Nishi Yoshio 西 義郎 (1974) "ビルマ文語の-acについて Birumabungo-no-ac-ni tsuite" [On -ac in Burmese] 東洋学報 Tōyō gakuhō. The Journal of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko 56.1: 01-43

- Nishi Yoshio (1999). Four Papers on Burmese: Toward the history of Burmese (the Myanmar language). Tokyo: Institute for the study of languages and cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies.

- Nishida Tatsuo 西田龍雄 (1955) "Myazedi 碑文における中古ビルマ語の研究 Myazedi hibu ni okeru chūko biruma go no kenkyū. Studies in the later ancient Burmese Language through Myazedi Inscriptions." 古代學 Kodaigaku Palaeologia 4.1:17-31 and 5.1: 22-40.

- Pān Wùyún 潘悟雲 (2000). "緬甸文元音的轉寫 Miǎndiàn wényuán yīn de zhuǎn xiě. [The Transliteration of Vowels of Burman Script].” 民族語文 Mínzú Yǔwén 2000.2: 17-21.

- Wāng Dànián 汪大年 (1983). "缅甸语中辅音韵尾的历史演变 Miǎndiànyǔ fǔyīn yùnwěi de lìshǐ yǎnbiàn [Historical evolution of Burmese finals." 民族语文 Mínzú Yǔwén 2: 41-50.

- Wun, Maung (1975). "Development of the Burmese language in the medieval period." 大阪外国語大学学報 Ōsaka gaikokugo daigaku gakuhō 36: 63-119.

- Yanson, Rudolf (1990). Вопросы фонологии древнебирманского языка. Voprosy fonologii drevnebirmanskogo jazyka. Moscow: Nauk.

- Yanson, Rudolf (2006). 'Notes on the evolution of the Burmese Phonological System.' Medieval Tibeto-Burman Languages II. Christopher I. Beckwith, ed. Leiden: Brill. 103-20.