Paecilomyces variotii

| Paecilomyces variotii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Phylum: | Ascomycota |

| Subphylum: | Pezizomycotina |

| Class: | Eurotiomycetes |

| Subclass: | Eurotiomycetidae |

| Order: | Eurotiales |

| Family: | Trichocomaceae |

| Genus: | Paecilomyces |

| Species: | P. variotii |

| Binomial name | |

| Penicillium aureocinnamomeum Biourge & Bainier | |

Paecilomyces variotii is a common environmental mold that is widespread in composts, soils and food products. It is known from substrates including food, indoor air, wood, soil and carpet dust.[1][2][3] Paecilomyces variotii is the asexual state of Byssochlamys spectabilis, a member of the Phylum Ascomycota (Family Trichocomaceae).[4] However, the Byssochlamys state is rarely observed in culture due to the heterothallic nature of this species (i.e., it requires culturing of positive and negative strains in co-culture to produce the teleomorph). Paecilomyces variotii is fast growing, producing powdery to suede-like in colonies that are yellow-brown or sand-colored.[5] It is distinguishable from microscopically from similar microfungi, such as the biverticillate members of the genus Penicillium (affiliated with the genus Talaromyces) by its broadly ellipsoidal to lemon-shaped conidia, loosely branched conidiophores and phialides with pointed tips. Ascospores of the sexual state, B. spectabilis, are strongly heat-resistant. As such, the fungus is a common contaminant of heat-treated foods and juices.[4] It is also known from decaying wood and creosote-treated wood utility poles.[4][5] Paecilomyces variotii has been associated with a number of infective diseases of humans and animals.[6] It is also an important indoor environmental contaminant.[7]

Morphology

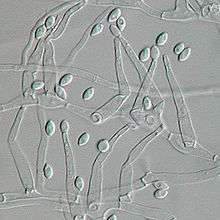

The colonies are usually flat, powdery to suede-like and funiculose or tufted.[8] The color is initially white, and becomes yellow, yellow-brown, or sand-colored as they mature. A sweet aromatic odor may be associated with older cultures.[9] Colonies of P. variotii are fast growing and mature within 3 days. Colonies grown on Sabouraud's dextrose agar reach about 7–8 mm after one week. Colonies on CYA are flat, floccose in texture, produce brown or olive brown from conidia, and range in diameter from 30-79 mmn in one week.[10] Colonies on malt extract agar reach 70 mm diameter or more, otherwise very similar in appearance to those on CYA. Colonies on G25N media reach 8–16 mm diameter, similar to on CYA but with predominantly white mycelium. Microscopically, the spore-bearing structures of P. variotii consist of a loosely branched,[11] irregularly brush-like conidiophores with phialides at the tips.[4][8] The phialides are swollen at the base, and gradually taper to a sharp point at the tip.[11] Conidia are single-celled, hyaline, and are borne in chains with the youngest at the base.[4] Chlamydospores (thick-walled vegetative resting structures) are occasionally produced singly or in short chains.[12]

Genetics

This fungus is heterothallic, and mating experiments have shown that P. variotii can form ascomata and ascospores in culture when compatible mating types are present.[1][4] Because of this, the teleomorph of P. variotii, Byssochlamys spectabilis, is rarely observed in cultures from environmental or clinical specimens which tend to be colonized by a single mating type.[4]

Ecology

This species is thermophilic, able to grow at high temperatures as high as 50–60 °C.[4][9] It can withstand brief exposures of up to 15 min at 80–100 °C.[13] Accordingly, it typically causes spoilage of food products following pasteurization or other heat-treatments (e.g., curry sauces, fruit juices).[14][15] It also has been reported as a contaminant in salami and margarine.[7] The fungus is known from a number of non-food items including compost, rubber, glue, urea-formaldehyde foam insulation and creosote-treated wooden poles.[7][14] The combination of its ability to survive significant heat stress and its ability to break-down aromatic hydrocarbons has led to interest in P. variotii as a potential candidate organism to assist in bioremediation.

Health significance

Although frequently encountered as a contaminant in clinical specimens, P. variotii is an uncommon causative agent of human and animal infections, but is considered to be an emerging agent of opportunistic disease, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. It has been suggested that the extremotolerant nature of the fungus contributes to the its pathogenic potential. Pneumonia due to P. variotii has been reported, albeit rarely, in the medical literature.[16][17] Most cases are known from diabetics or individuals subject to long-term corticosteroid treatment for other diseases.[18][19] Paecilomyces variotii has also been reported as a causative agent of sinusitis,[20][21][22] endophthalmitis,[23][24][25] wound infection following tissue transplant,[26] cutaneous hyalohyphomycosis,[27][28][29] onychomycosis,[30] osteomyelitis,[31] otitis media[32] and dialysis-related peritonitis.[6] It has also been reported from mastitis in a goat, and as an agent of mycotic infections of dogs and horses.[33] Besides clinical samples, the fungus is a common contaminant of moisture-damaged materials in the indoor environment including carpet, plaster and wood.[7] It is commonly found in indoor air samples and may contribute to indoor allergy.[7] This species produces the mycotoxin, viriditoxin.[7]

References

- 1 2 Houbraken, J; J. Varga; E. Rico-Munoz; S. Johnson; R. A. Samson (2008). "Sexual Reproduction as the Cause of Heat Resistance in the Food Spoilage Fungus Byssochlamys Spectabilis (Anamorph Paecilomyces Variotii).". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 74 (5): 1613–619. doi:10.1128/aem.01761-07.

- ↑ Pitt, J.L; A. D. Hocking (2009). Fungi and food spoilage, 3rd ed. ).

- ↑ Steiner, Bruna; Valerio R. A.,1 Alessandra A. P.,2 Lucia Mariano da Rocha Silla,2 Alexandre Z.,1 and Luciano Z. G. (January 2011). "Apophysomyces variabilis as an Emergent Pathogenic Agent of Pneumonia". Hindawi Diseases. 17 (1): 134–135. doi:10.3201/eid1701.101139. PMC 3204648

. PMID 21192877. Cite uses deprecated parameter

. PMID 21192877. Cite uses deprecated parameter |coauthors=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Houbraken, J; P. E. Verweij; A. J. M. M. Rijs; A. M. Borman; R. A. Samson (2010). "Identification of Paecilomyces variotii in Clinical Samples and Settings.". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 48: 2754–761. doi:10.1128/jcm.00764-10.

- 1 2 Ellis, David (May 2001). "Paecilomyces variotii." Mycology Online". The University of Adelaide.

- 1 2 59-61, S; E. Fiscarelli; G. Rizzoni (2000). "Paecilomyces variotii peritonitis in an infant on automated peritoneal dialysis". Pediatr. Nephrol. 14: 365–366. doi:10.1007/s004670050775.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Samson, R. A.; J. Houbraken; R. C. Summerbell; B. Flannigan; J. D. Miller (2001). "Common and important species of fungi and actinomycetes in indoor environment,". Microorganisms in home and indoor work environments: 287–474.

- 1 2 Bainier, D (Nov 2013). "Paecilomyces Species.". Paecilomyces Species.

- 1 2 de Hoog, G.S.; J. Guarro; J. Gene; M. J. Figueras. Atlas of Clinical Fungi, 2nd ed, vol. 1. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures.

- ↑ Pitt, John; Ailsa D. Hocking (1985). "Fungi and Food Spoilage". Sydney: Academic: 186–96.

- 1 2 Samson, R. A (1974). "Paecilomyces and some allied hyphomycetes.Stud. Mycol". 6: 1–119.

- ↑ "Paecilomyces and Some Allied HyphomycetesBy R. A. Sampson". Transactions of the British Mycological Society. 64: 174. 1975. doi:10.1016/s0007-1536(75)80098-2.

- ↑ Pieckov, E; R. A. Samson (2000). "Heat Resistance of Paecilomyces Variotii in Sauce and Juice". Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology. 24: 227–30. doi:10.1038/sj.jim.2900794.

- 1 2 Samson, R.A; E. S. Hoekstra; J. C. Frisvad (2004). Introduction to food- and airborne fungi, 7th ed. Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures.

- ↑ Piecková, ES; Samson RA (2000). ". Heat resistance of Paecilomyces variotii in sauce and juice". Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology. 24: 227–230. doi:10.1038/sj.jim.2900794.

- ↑ Saddad, N.; H. Shigemitsu; A. Christianson (2007). "Pneumonia from Paecilomyces in a 67-year-old immunocompetent man". Chest. 132: 710. doi:10.1378/chest.132.4_meetingabstracts.710.

- ↑ Grossman, C. E; A. Fowler (2005). "Paecilomyces: emerging fungal pathogen". Chest. 128: 425S. doi:10.1378/chest.128.4_meetingabstracts.425s.

- ↑ Byrd,, R. P.; Jr., T. M. Roy, C. L. Fields, and J. A. Lynch (1992). "Paecilomyces variotii pneumonia in a patient with diabetes mellitus. J.". Diabetes Complicat. 6: 150–153. doi:10.1016/1056-8727(92)90027-i. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Steiner, Bruna; Valerio R. Aquino, Alessandra A. Paz, Lucia Mariano da Rocha Silla, Alexandre Zavascki, and Luciano Z. Goldani (2013). "Valerio R. Aquino, Alessandra A. Paz, Lucia Mariano da Rocha Silla, Alexandre Zavascki, and Luciano Z. Goldani". Case Reports in Infectious Diseases. 2013. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ Eloy, P.; B. Bertrand; P. Rombeaux; M. Delos; J. P. Trigaux (1997). "Mycotic sinusitis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol". Belg. 51: 339–352.

- ↑ Otcenasek, M; Z. Jirousek; Z. Nozicka; K. Mencl (1984). "Paecilomycosis of the maxillary sinus". Mykosen. 27: 242–251.

- ↑ 12. Thompson, R. F; R. B. Bode; J. C. Rhodes; J. L. Gluckman (1988). "Paecilomyces variotii. An unusual cause of isolated sphenoid sinusitis.". Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 114: 567–569. doi:10.1001/archotol.1988.01860170097028. horizontal tab character in

|last=at position 4 (help) - ↑ Lam, D. S; A. P. Koehler; D. S. Fan; W. Cheuk; A. T. Leung; J. S. Ng (1999). "Endogenous fungal endophthalmitis caused by Paecilomyces variotii.". Eye. 13: 113–116. doi:10.1038/eye.1999.23.

- ↑ Tarkkanen, A; V. Raivio; V. J. Anttila; P. Tommila; R. Ralli; L. Merenmies; I. Immonen (2004). "Fungal endophthalmitis caused by Paecilomyces variotii following cataract surgery: a presumed operating room air-conditioning system contamination.". Acta Ophthalmol. 82: 232–235. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0420.2004.00235.x.

- ↑ Anita, KB.V; V. Fernandez; R. Rao (2010). "Fungal Endophthalmitis Caused by Paecilomyces Variotii, in an Immunocompetent Patient, following Intraocular Lens Implantation.". Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology. 28 (3): 253. doi:10.4103/0255-0857.66491.

- ↑ Lee, J; W. W. Yew; C. S. Chiu; P. C. Wong; C. F. Wong; E. P. J. Wang (2002). "Delayed sternotomy wound infection due to Paecilomyces variotii in a lung transplant recipient". Heart Lung Transplant. 21: 1131–1134. doi:10.1016/s1053-2498(02)00404-7.

- ↑ Athar, M. A.; A. S. Sekhon; J. V. Mcgrath; R. M. Malone (1996). "Hyalohyphomycosis caused by Paecilomyces variotii in an obstetrical patient". Eur. J. Epidemiol. 12: 33–35. doi:10.1007/bf00144425.

- ↑ Naidu, J; S. M. Singh (1992). "Hyalohyphomycosis caused by Paecilomyces variotii: a case report, animal pathogenicity and 'in vitro' sensitivity". Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 62: 225–230. doi:10.1007/bf00582583.

- ↑ Vasudevan, B; Hazra, N.; Verma, R.; Srinivas, V.; Vijendran, P.; Badad, A. (2013). "First reported case of subcutaneous hyalohyphomycosis caused by Paecilomyces variotii.". International Journal of Dermatology. 52: 711–713. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2012.05761.x.

- ↑ Arenas, R; M. Arce; H. Munoz; J. Ruiz-Esmenjaud (1998). "Onychomycosis due to Paecilomyces variotii. Case report and review". J. Mycol. Med. 8: 32–33.

- ↑ Cohen-Abbo, A; K. M. Edwards (1995). ". Multifocal osteomyelitis caused by Paecilomyces variotii in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease". Infection. 23: 55–57. doi:10.1007/bf01710060.

- ↑ Dhindsa, M. K.; J. Naidu; S. M. Singh; S. K. Jain (1995). "Chronic suppurative otitis media caused by Paecilomyces variotii.". J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 33: 59–61. doi:10.1080/02681219580000121.

- ↑ Marzec, A; Heron L G; Pritchard R.C; Butcher R.H; Powell H.R.; Disney A.P; Tosolini F.A. (September 1993). "Paecilomyces variotii in peritoneal dialysate.". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 31: 2392–2395.