Teide

| Teide | |

|---|---|

Teide seen from the north | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 3,718 m (12,198 ft) [1] |

| Prominence |

3,718 m (12,198 ft) [1] Ranked 40th |

| Isolation | 895 kilometres (556 mi) |

| Listing |

Country high point Ultra |

| Coordinates | 28°16′23″N 16°38′22″W / 28.27306°N 16.63944°WCoordinates: 28°16′23″N 16°38′22″W / 28.27306°N 16.63944°W [1] |

| Geography | |

Teide Location of Teide in the Canary Islands | |

| Location | Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano atop basalt shield volcano |

| Last eruption | November 1909 |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 1582 |

| Easiest route | Scramble |

Mount Teide (Spanish: Pico del Teide, pronounced: [ˈpiko ðel ˈtei̯ðe], "Teide Peak") is a volcano on Tenerife in the Canary Islands, Spain. Its 3,718-metre (12,198 ft) summit is the highest point in Spain and the highest point above sea level in the islands of the Atlantic.

If measured from its base on the ocean floor, it is at 7,500 m (24,600 ft) the third highest volcano on a volcanic ocean island in the world after Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa in Hawaii.[2] Its elevation makes Tenerife the tenth highest island in the world. It remains active: its most recent eruption occurred in 1909 from the El Chinyero vent on the northwestern Santiago rift. The United Nations Committee for Disaster Mitigation designated Teide a Decade Volcano[3] because of its history of destructive eruptions and its proximity to several large towns, of which the closest are Garachico, Icod de los Vinos and Puerto de la Cruz. Teide, Pico Viejo and Montaña Blanca form the Central Volcanic Complex of Tenerife.

The volcano and its surroundings comprise Teide National Park, which has an area of 18,900 hectares (47,000 acres) and was named a World Heritage Site by UNESCO on June 28, 2007.[4] Teide is the most visited natural wonder of Spain, the most visited national park in Spain and Europe and – by 2015 – the eighth most visited in the world,[5] with some 3 million visitors yearly.[6] A major international astronomical observatory is located on the slopes of the mountain.

Name

Before the 1495 Spanish colonization of Tenerife, the native Guanches called the volcano Echeyde, which in their legends referred to a powerful figure leaving the volcano, which could turn into hell. El Pico del Teide is the modern Spanish name.

Legends

Teide was a sacred mountain for the aboriginal Guanches, so it was considered a mythological mountain, as Mount Olympus was to the ancient Greeks. According to legend, Guayota (the devil) kidnapped Magec (the god of light and the sun) and imprisoned him inside the volcano, plunging the world into darkness. The Guanches asked their supreme god Achamán for clemency, so Achamán fought Guayota, freed Magec from the bowels of the mountain, and plugged the crater with Guayota. It is said that since then, Guayota has remained locked inside Teide. When going on to Teide during an eruption, it was customary for the Guanches to light bonfires to scare Guayota. Guayota is often represented as a black dog, accompanied by his host of demons (Tibicenas).

The Guanches also believed that Teide held up the sky. Many hiding places found in the mountains contain the remains of stone tools and pottery. These have been interpreted as being ritual deposits to counter the influence of evil spirits, like those made by the Berbers of Kabylie. The Guanches believed the mountain to be the place that housed the forces of evil and the most evil figure, Guayota.[7]

Guayota shares features similar to other powerful deities inhabiting volcanoes, such as the goddess Pele of Hawaiian mythology, who lived in the Kīlauea volcano and was regarded by the native Hawaiians as responsible for the eruptions of the volcano.[8]

Formation

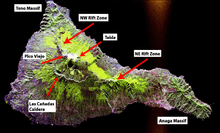

The stratovolcanoes Teide and Pico Viejo (Old Peak, although it is in fact younger than Teide) are the most recent centres of activity on the volcanic island of Tenerife, which is the largest (2,058 km2 or 795 sq mi) and highest (3,718 m or 12,198 ft) island in the Canaries. It has a complex volcanic history. The formation of the island and the development of the current Teide volcano took place in the five stages shown in the diagram on the right.

Stage one

Like the other Canary Islands, and volcanic ocean islands in general, Tenerife was built by accretion of three large shield volcanoes, which developed in a relatively short period of time.[9] This early shield stage volcanism formed the bulk of the emerged part of Tenerife. The shield volcanoes date back to the Miocene and early Pliocene[10] and are preserved in three isolated and deeply eroded massifs: Anaga (to the northeast), Teno (to the northwest) and Roque del Conde (to the south).[11] Each individual shield was apparently constructed in less than three million years, and the entire island in about eight million years.[12]

Stages two and three

The initial juvenile stage was followed by a period of 2–3 million years of eruptive quiescence and erosion. This cessation of activity is typical of the Canaries; La Gomera, for example, is currently at this stage.[13] After this period of quiescence, the volcanic activity became concentrated within two large edifices: the central volcano of Las Cañadas, and the Anaga massif. The Las Cañadas volcano developed over the Miocene shield volcanoes and may have reached 40 km (25 mi) in diameter and 4,500 m (14,800 ft) in height.[14]

Stage four

Around 160–220 thousand years ago the summit of the Las Cañadas I volcano collapsed, creating the Las Cañadas (Ucanca) caldera.[12] Later a fresh stratovolcano, Las Cañadas II, re-formed and underwent catastrophic collapse. Detailed mapping indicates that the site of this volcano was in the vicinity of Guajara. The Las Cañadas III volcano formed in the Diego Hernandez sector of the caldera. Detailed mapping indicates that all the Las Cañadas volcanoes attained a maximum altitude similar to that of Teide (which is also referred to as the Las Cañadas IV volcano).

Two theories on the formation of the 16 km × 9 km (9.9 mi × 5.6 mi) caldera exist.[15] The first states that the depression is the result of a vertical collapse of the volcano triggered by the emptying of shallow magma chambers at around sea level under the Las Cañadas volcano after large-volume explosive eruptions.[12][16][17] The second theory is that the caldera was formed by a series of lateral gravitational collapses similar to those described in Hawaii.[18] Evidence for the latter theory has been found in both onshore observations[19][20][21] and marine geology studies.[12][22]

Stage five

From around 160 thousand years ago until the present day, the stratovolcanoes of Teide and Pico Viejo formed within the Las Cañadas caldera.

Historical eruptions

Teide last erupted in 1909 from the El Chinyero vent,[12] on the Santiago Ridge. Historical volcanic activity on the island is associated with vents on the Santiago or northwest rift (Boca Cangrejo in 1492, Montañas Negras in 1706,[12] Narices del Teide or Chahorra in 1798 and El Chinyero in 1909) and the Cordillera Dorsal or northeast rift (Fasnia in 1704, Siete Fuentes and Arafo in 1705). The 1706 Montañas Negras eruption destroyed the town and principal port of Garachico, as well as several smaller villages.

Historical activity associated with the Teide and Pico Viejo stratovolcanoes [12] occurred in 1798 from the Narices del Teide on the western flank of Pico Viejo. Eruptive material from Pico Viejo, Montaña Teide and Montaña Blanca partially fills the Las Cañadas caldera.[11] The last explosive eruption involving the central volcanic centre was from Montaña Blanca around 2000 years ago. The last eruption within the Las Cañadas caldera occurred in 1798 from the Narices del Teide or Chahorra (Teide's Nostrils) on the western flank of Pico Viejo. The eruption was predominantly strombolian in style and most of the lava was ʻAʻā. This lava is visible beside the Vilaflor–Chio road.

Christopher Columbus reported seeing "a great fire in the Orotava Valley" as he sailed past Tenerife on his voyage to discover the New World in 1492. This was interpreted as indicating that he had witnessed an eruption there. Radiometric dating of possible lavas indicates that in 1492 no eruption occurred in the Orotava Valley, but one did occur from the Boca Cangrejo vent.[12]

The last summit eruption from Teide occurred about the year 850 CE, and this eruption produced the "Lavas Negras" or "Black Lavas" that cover much of the flanks of the volcano.[12]

About 150,000 years ago, a much larger explosive eruption occurred, probably of Volcanic Explosivity Index 5. It created the Las Cañadas caldera, a large caldera at about 2,000 m above sea level, around 16 km (9.9 mi) from east to west and 9 km (5.6 mi) from north to south. At Guajara, on the south side of the structure, the internal walls rise as almost sheer cliffs from 2,100 to 2,715 m (6,890 to 8,907 ft). The 3,718 m (12,198 ft) summit of Teide itself, and its sister stratovolcano Pico Viejo (3,134 m (10,282 ft)), are both situated in the northern half of the caldera and are derived from eruptions later than this prehistoric explosion.

.svg.png)

Potential eruptions

Future eruptions may include pyroclastic flows and surges similar to those that occurred at Mount Pelée, Merapi, Vesuvius, Etna, Soufrière Hills, Mount Unzen and elsewhere. During 2003, there was an increase in seismic activity at the volcano and a rift opened on the north-east flank. No eruptive activity occurred but a volume of material - possibly liquid, was emplaced into the edifice and is estimated to have a volume of ~1011 m3. Such activity can indicate that magma is rising into the edifice, but is not always a precursor to an eruption.

Teide additionally is considered structurally unstable and its northern flank has a distinctive bulge. The summit of the volcano has a number of small active fumaroles emitting sulfur dioxide and other gases, including low levels of hydrogen sulfide.

A recent study showed that Teide will probably erupt violently in the future, and that its structure is similar to that of Vesuvius and Etna.[23]

Major climbs

In a publication of 1626, Sir Edmund Scory, who probably stayed on the island in the first decades of the 17th century, gives a description of Teide, in which he notes the suitable paths to the top and the effects the considerable height causes to the travellers, indicating that the volcano had been accessed via different routes before the 17th century.[24] In 1715 the English traveler J. Edens and his party made the ascent and reported their observations in the journal of the Royal Society in London.[25]

After the Enlightenment, most of the expeditions that went to East Africa and the Pacific had Teide as one of the most rewarding targets. The expedition of Lord George Macartney, George Staunton and John Barrow in 1792 almost ended in tragedy, as a major snowstorm and rain swept over them and they failed to reach the peak of Teide, just barely getting past Montaña Blanca.[25]

During an expedition to Kilimanjaro, the German adventurer Hans Heinrich Joseph Meyer visited Teide in 1894 to observe ice conditions on the volcano. He described the two mountains as "two kings, one rising in the ocean and the other in the desert and steppes".[25]

Flora and fauna

The lava flows on the flanks of Teide weather to a very thin but nutrient- and mineral-rich soil that supports a wide variety of plant species. Vascular flora consists of 168 plant species, 33 of which are endemic to Tenerife.[26]

Forests of Canary Island Pine (Pinus canariensis) with Canary Island juniper (Juniperus cedrus) occur from 1,000 to 2,100 metres (3,300–6,900 ft), covering the middle slopes of the volcano and reaching an alpine tree line 1,000 m (3,300 ft) lower than that of continental mountains at similar latitudes.[27][28] Within the Las Cañadas caldera and at higher altitudes, plant species endemic to the Teide National Park include: the Teide white broom (Spartocytisus supranubius), which has white flowers; Descurainia bourgaeana, a shrubby crucifer with yellow flowers; the Canary Island wallflower (Erysimum scoparium), which has violet flowers; and the Teide bugloss (Echium wildpretii), whose red flowers form a pyramid up to 3 m (9.8 ft) in height.[29] The Teide daisy (Argyranthemum teneriffae) can be found at altitudes close to 3,600 m (11,800 ft) above sea level, and the Teide violet (Viola cheiranthifolia) can be found right up to the summit, making it the highest flowering plant in Spain.[30]

These plants are adapted to the tough environmental conditions on the volcano, such as high altitude, intense sunlight, extreme temperature variations, and lack of moisture. Adaptations include hemispherical forms, a downy or waxy cover, a reduction of the exposed leaf area, and a high flower production.[28][31] Flowering takes place in the late spring or early summer, in May and June.[26]

Teide National Park contains a large number of invertebrate species, over 40% of which are endemic species, and 70 of which are found only in the National Park. The invertebrate fauna includes spiders, beetles, dipterans, hemipterans, and hymenopterae.[32]

In contrast, Teide National Park has only a limited variety of vertebrate fauna.[33] Ten species of bird nest there, including the blue chaffinch (Fringilla teydea teydea), Berthelot's pipit (Anthus berthelotii berthelotii), the Atlantic canary (Serinus canaria) and a subspecies of kestrel (Falco tinnunculus canariensis).[34][35]

Three endemic reptile species are found in the park: the Canary Island lizard (Gallotia galloti galloti), the Canary Island wall gecko (Tarentola delalandii), and the Canary Island skink (Chalcides viridanus viridanus).[33][36] The only mammals native to the park are bats, the most common of which is Leisler’s bat (Nyctalus leisleri). Other mammals, such as the mouflon, the rabbit, the house mouse, the black rat, the feral cat, and the North African hedgehog, have all been introduced to the park.[37]

Scientific use

Teide National Park is a useful volcanic reference point for studies related to Mars because of the similarities in their environmental conditions and geological formations.[38] In 2010 a research team tested the Raman instrument at Las Cañadas del Teide in anticipation of its use in the 2016–2018 ESA-NASA ExoMars expedition.[38] In June 2011 a team of researchers from the UK visited the park to test a method for looking for life on Mars and to search for suitable places to test new robotic vehicles in 2012.[39]

Access

The volcano and its surroundings, including the whole of the Las Cañadas caldera, are protected in the Teide National Park. Access is by a public road running from northeast to southwest across the caldera. TITSA runs a return service to Teide once a day from both Puerto de la Cruz and Playa de las Americas. The park has a parador (hotel) and a small chapel. A cable car goes from the roadside at 2,356 m (7,730 ft) most of the way to the summit, reaching 3,555 m (11,663 ft), carrying up to 38 passengers (34 in a high wind) and taking eight minutes to reach the summit. Queues can exceed two hours in peak season. Access to the summit itself is restricted; a free permit is required to climb the last 200 m (660 ft). Numbers are normally restricted to 200 per day.

Several footpaths take hikers to the upper cable car terminal, and then onto the summit (with the permit). The most popular route is via the Refugio de Altavista, however these are demanding hikes requiring at least 4–5 hours of ascent.

Because of the altitude, the air is significantly thinner than at sea level. This can cause people (especially with heart or lung conditions) to become light-headed or dizzy, to develop altitude sickness, and in extreme cases to lose consciousness. The only treatment is to return to lower altitudes and acclimatise.

Astronomical observatory

An astronomical observatory is located on the slopes of the mountain, taking advantage of the altitude (above most clouds), good weather and stable seeing from the site. The Teide Observatory is operated by the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias. It includes solar, radio and microwave telescopes, in addition to traditional optical night-time telescopes.

Symbol

Teide is the main symbol of Tenerife and the most emblematic natural monument of the Canary Islands. An image of Teide appears gushing flames at the centre of Tenerife's coat of arms. Above the volcano appears St. Michael, the patron saint of Tenerife. The flag colors of the island are dark blue, traditionally identified with the sea that surrounds the island, and white for the whiteness of the snow-covered peaks of Mount Teide during winter.

Teide has been depicted frequently throughout history, from the earliest engravings made by European conquerors to typical Canarian craft objects, on the back of 1000-peseta notes, in oil paintings and on postcards.

Coat of arms of Tenerife

Coat of arms of Tenerife

Mountain of the Moon

Mons Pico, one of the Montes Teneriffe range of lunar mountains in the inner ring of the Mare Imbrium, was named by Johann Hieronymus Schröter after the Pico von Teneriffe, an 18th-century name for Teide.[7][40]

Gallery

Teide from Llano de Ucanca

Teide from Llano de Ucanca Teide and Pico Viejo

Teide and Pico Viejo.jpg) Teide from Llano de Ucanca

Teide from Llano de Ucanca.jpg) The snow-capped summit of Teide in December 2004

The snow-capped summit of Teide in December 2004 Snow-capped Teide from the north, March 2006

Snow-capped Teide from the north, March 2006 Teide from the air

Teide from the air- The small church at the foot of the mountain

The cable car on Teide

The cable car on Teide Teide from Cañada de los Guancheros at 2050 m

Teide from Cañada de los Guancheros at 2050 m Astronaut photograph of Teide

Astronaut photograph of Teide%2C_Mount_Teide_(right_side_of_the_image)._Tenerife%2C_Canary_Islands%2C_Spain%2C_Southwestern_Europe.jpg) View overlooking Teide National Park (World Heritage Site), Mount Teide on the left

View overlooking Teide National Park (World Heritage Site), Mount Teide on the left

See also

- Teide National Park

- Roque Cinchado

- Mount Guajara

- Pico Viejo

- Tenerife

- List of tallest mountains in the Solar System

References

- 1 2 3 "Europe: Atlantic Islands – Ultra Prominences" on peaklist.org as "Pico de Teide". Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ↑ "Tenerife: El Parque Nacional del Teide". Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ↑ http://vulcan.wr.usgs.gov/Volcanoes/DecadeVolcanoes/ Decade Volcanoes – USGS

- ↑ "Teide National Park". World Heritage List. UNESCO. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- ↑ En las entrañas del volcán|El Español

- ↑ "Parque Nacional del Teide. Ascenso, Fauna, Flora...". Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- 1 2 Sheehan, William & Baum, Richard, Observation and inference: Johann Hieronymous Schroeter, 1745–1816, JBAA 105 (1995), 171

- ↑ "Ethnografia y anales de la conquista de las Islas Canarias". Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ↑ Guillou, H., Carracedo, J. C., Paris R. and Pérez Torrado, F.J., 2004a. K/Ar ages and magnetic stratigraphy of the Miocene-Pliocene shield volcanoes of Tenerife, Canary Islands: Implications for the early evolution of Tenerife and the Canarian Hotspot age progression. Earth & Planet. Sci. Letts., 222, 599–614.

- ↑ Fúster, J.M., Araña, V., Brandle, J.L., Navarro, J.M., Alonso, U., Aparicio, A., 1968. Geology and volcanology of the Canary Islands: Tenerife. Instituto Lucas Mallada, CSIC, Madrid, 218 pp

- 1 2 Carracedo, Juan Carlos; Day, Simon (2002). Canary Islands (Classic Geology in Europe 4). Terra Publishing, 208 pp. ISBN 1-903544-07-6

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Carracedo, J. C., Rodríguez Badioloa, E., Guillou, H., Paterne, M., Scaillet, S., Pérez Torrado, F. J., Paris, R., Fra-Paleo, U., Hansen, A., 2007. "Eruptive and structural history of Teide Volcano and rift zones of Tenerife, Canary Islands." Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, 119(9–10). 1027–1051

- ↑ Paris, R, Guillou, H., Carracedo, JC and Perez Torrado, F.J., Volcanic and morphological evolution of La Gomera (Canary Islands), based on new K-Ar ages and magnetic stratigraphy:implications for oceanic island evolution, Journal of the Geological Society, May 2005, v.162; no.3; p.501-512

- ↑ Carracedo, J.C., Pérez Torrado, F.J., Ancochea, E., Meco, J., Hernán, F., Cubas, C.R., Casillas, R., Rodríguez Badiola, E. and Ahijado, A., 2002. In: Cenozoic Volcanism II: the Canary Islands. The Geology of Spain (W. Gibbons and T. Moreno, eds), pp. 439–472. Geological Society, London

- ↑ "Tenerife". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- ↑ Martí, J., Mitjavila, J., Araña, V., 1994. Stratigraphy, structure and geochronology of the Las Cañadas Caldera (Tenerife, Canary Islands). Geol. Mag. 131: 715–727

- ↑ Martí. J. and Gudmudsson, A., 2000. The Las Cañadas caldera (Tenerife, Canary Islands): an overlapping collapse caldera generated by magma-chamber migration. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 103: 167–173

- ↑ Moore, J. G., 1964. Giant submarine landslides on the Hawaiian Ridge. U.S. Geol. Surv. Prof. Pap., 501-D, D95-D98

- ↑ Carracedo, J.C., 1994. The Canary Islands: an example of structural control on the growth of large oceanic island volcanoes. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 60: 225–242

- ↑ Guillou, H., Carracedo, J.C., Pérez Torrado, F. and Rodríguez Badiola, E., 1996. K-Ar ages and magnetic stratigraphy of a hotspot-induced, fast grown oceanic island : El Hierro, Canary Islands. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 73: 141–155

- ↑ Stillman, C.J., 1999. Giant Miocene Landslides and the evolution of Fuerteventura, Canary Islands J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 94, pp. 89–104

- ↑ Masson, D.G., Watts, A.B., Gee, M.J.R., Urgelés, R., Mitchell, N.C., Le Bas, T.P., Canals, M., 2002. Slope failures on the flanks of the western Canaested in the embayment itself.

- ↑ Un estudio prevé que el Teide sufriría erupciones violentas (La Opinión.es)

- ↑ Francisco Javier Castillo, The English Renaissance and the Canary Islands: Thomas Nichols and Edmund Scory, Proceedings of the II Conference of SEDERI: 1992: 57-69

- 1 2 3 "El Parque Nacional del Teide: patrimonio mundial de la UNESCO, con Juan Carlos Carracedo y Manuel Durbán - Nicolás González Lemus". Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- 1 2 Dupont, Yoko L., Dennis M., Olesen, Jens M., Structure of a plant-flower-visitor network in the high altitude sub-alpine desert of Tenerife, Canary Islands, Ecography. 26(3), 2003, pp. 301–310.

- ↑ Gieger, Thomas and Leuschner, Christoph. Altitudinal change in needle water relations of the Canary pine (Pinus Canariensis) and possible evidence of a drought-induced alpine timberline on Mt. Teide, Tenerife, Flora – Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants, 199(2), 2004, Pages 100-109y

- 1 2 J.M. Fernandez-Palacios, Climatic response of plant species on Tenerife, the Canary islands, J. Veg. Sci. 3, 1992, pp. 595–602

- ↑ "Tenerife National Park – Flora". Tenerife Tourism Corporation. Archived from the original on June 14, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2007.

- ↑ J.M. Fernandez-Palacios and J.P. de Nicolas, Altitudinal pattern of vegetation variation on Tenerife, J. Veg. Sci. 6, 1995, pp. 183–190

- ↑ C. Leuschner, Timberline and alpine vegetation on the tropical and warm-temperate oceanic islands of the world: elevation, structure and floristics, Vegetatio 123, 1996, pp. 193–206.

- ↑ Ashmole, M. and Ashmole, P. (1989) Natural History Excursions in Tenerife. Kidston Mill Press, Scotland. ISBN 0 9514544 0 4.

- 1 2 Thorpe, R.S., McGregor, D.P., Cumming, A.M., and Jordan, W.C., DNA evolution and colonisation sequence of island lizards in relation to geological history: mtDNA RFLP, cytochrome B, cytochrome oxidase, 12s rRNA sequence, and nuclear RAPD analysis, Evolution, 48(2), 1994, pp. 230–240

- ↑ Lack, D., and H.N. Southern. 1949. Birds of Tenerife. Ibis, 91:607–626

- ↑ P.R. Grant, "Ecological compatibility of bird species on islands", Amer. Nat., 100(914), 1966, pp. 451–462.

- ↑ Lever, Christopher (2003). Naturalized Reptiles and Amphibians of the World (First ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850771-0.

- ↑ Nogales, M., Rodríguez-Luengo, J.L. & Marrero, P. (2006) "Ecological effects and distribution of invasive non-native mammals on the Canary Islands" Mammal Review, 36, 49–65

- 1 2 Unidad Editorial Internet (November 3, 2010). "Tenerife se convierte en un laboratorio marciano - Ciencia - elmundo.es". Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ↑ Buscando "marcianos" en el Teide

- ↑ Schroeter, Johann Hieronymous, Selenotopographische Fragmente sur genauern Kenntniss der Mondfläche [vol. 1]. – Lilienthal: auf Kosten des Verfassers, 1791

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Teide. |

- UNESCO World Heritage Site datasheet

- Teide National Park—Official Website

- Teide Webcam

- Cable car

- (Spanish) Description of the ascent of Mount Teide

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Geminid Meteors over Teide Volcano (December 17, 2013)