Paul Touvier

Paul Claude Marie Touvier (April 3, 1915 – July 17, 1996) was a Nazi collaborator in Occupied France during World War II. In 1994, Touvier became the first Frenchman to be convicted of crimes against humanity.

Early life

Paul Touvier was born in Saint-Vincent-sur-Jabron, Alpes de Haute-Provence, in southeastern France. His family was devoutly Roman Catholic, lower middle class and extremely conservative.[1][2] He was one of 11 children,[2] and the oldest of the five boys.[1] Serving as an altar boy when young, he attended a seminary for a year, intending to become a priest.[1]

Touvier's mother, Eugenie, was an orphan who was raised by nuns. As an adult, she was very religious and went to Mass every day.[1] She died when Touvier was an adolescent.[2] His father, François Touvier, was a tax collector in Chambéry, after serving 19 years in the French Army.[1] Touvier's father was vehemently opposed to the anti-clerical legislation promulgated by the Third Republic and was a supporter of Charles Maurras and L'Action Française, both of which advocated a monarchist restoration in France.[1]

Paul Touvier graduated from the Institute St. Francis de Sales in Chambéry at the age of 16. When he turned 21, his father got him a job as a clerk at the local railroad station, where he continued to work as World War II began.[2] Widowed on the eve of the war, he continued to reside in Chambéry. Touvier was mobilized for the war effort in 1939. After the Vichy government was created, Touvier and his family were firm supporters of Maréchal Petain. They both joined the Vichy veterans' group when it was founded in 1941.[1]

War years

Joining the French Army's 8th Infantry Division, Touvier fought against the German Wehrmacht until, following the bombing of Château-Thierry, he deserted. Touvier returned in 1940 to Chambéry, which was then occupied by the Kingdom of Italy. His life took a new course after the Milice was established.

According to Ted Morgan,

Paul Touvier was assigned to expedite packages for prisoners of war, which got him into a spot of trouble, for he was caught removing the chocolate and the cigarettes from some of the packages. With these rationed articles he could impress girls. It should also be noted that Touvier was unusually good-looking, almost pretty, with wavy blond hair, delicate features and deep-set, intense blue eyes. He got a girl pregnant; the baby was turned over to a Catholic orphanage. All this did not sit well with Touvier pere. When Vichy Premier Pierre Laval formed the Milice, an armed pro-German militia, in February 1943, the father told his son to join, hoping it would put some backbone into him.[1]

According to Morgan,

Touvier went into the 2d Section in Chambery, which gathered intelligence. He found he was good at organizing files and recruiting informants and tailing suspects. He was so good, in fact, that he came to the attention of the inspectors from Vichy, who in September 1943 sent him to Lyons to be regional director. Lyons was a hub for both the Resistance and the Gestapo, whose Section 4, under Klaus Barbie, and Section 6, under August Moritz, were models of application in their pursuit of Resistance members and Jews. Both these offices made ample use of the Milice in carrying out their operations. Paul Touvier found that his job was not only collecting intelligence but taking part in arrests and other actions. In December 1943, at the instigation of the Gestapo, Touvier and his men raided a synagogue where some Jewish refugees were reportedly hiding. They found only a caretaker couple, and arrested them in front of their young daughter, who years later identified Touvier. The parents were deported to Auschwitz and did not return. Touvier may also have been connected, through the chain of command, to the murders of Victor Basch and his wife, on Jan. 11, 1944, although documents show that he was not present when the crime was committed. Basch, who today has a street in Lyons named after him, was president of the League of the Rights of Man, the most important French civil rights group. In 1944, he was 80, and his wife was 75. The two were arrested in their home in a combined Milice-Gestapo operation, taken to a spot on the banks of the Rhone river and shot. In April 1944, Touvier led a raid outside Lyons, on the fairgrounds in the town of Montmelian, five miles from Chambery, and rounded up 57 Spanish refugees, who were deported to the camps. Only nine returned, three of whom later identified him.[1]

Also according to Morgan,

He was notorious for his racketeering among the Jews, to whom he would promise protection at a price. He was notorious for taking the apartments and the property of those he arrested. In tape-recorded reminiscences he made in 1969 to a priest, Msgr. Charles Duquaire, Touvier said, "For me, what I did was legal. I was told, 'You will requisition the apartments of Jews.' I did it. 'You need cars, you'll requisition them.' I therefore requisitioned cars ... You could call that theft. For me it was requisitioning."[1]

Touvier carried out the murder of seven Jewish hostages at Rillieux-la-Pape near Lyon, on 29 June 1944. This was in retaliation for the assassination the previous evening of Philippe Henriot, the Vichy Government's Secretary of State for Information and Propaganda. Following his arrest in 1989, Touvier admitted his involvement in the massacre. He alleged, however, that Klaus Barbie had originally demanded the shooting of 30 Jews in retaliation for Henriot's murder. Touvier claimed to have negotiated the number down to 7.

At his 1994 trial, Touvier testified,

Right to the end, I tried to find another solution. We tried to reduce the number of victims from 30. I said we would do seven at a time. We could not avoid the catastrophe. But I did, even so, save 23 human lives.[3]

Post liberation

After the liberation of France by the Allied forces, Touvier went into hiding; he escaped the summary execution suffered by many suspected collaborators. On September 10, 1946, the French State sentenced him to death in absentia for treason and collusion with the Nazis.

According to Ted Morgan,

He knew he couldn't stay in the Lyons area, so he went to Montpellier, in the south of France, and bought a boarding house. He remained there until 1946, when, for reasons as yet unexplained, he sold the property and went to Paris, where he joined a gang of other wanted collaborators involved in various illegal activities. They made bootleg chocolate, which they sold out of suitcases to candy stores. They passed counterfeit bills. "Sometimes we spent days folding and unfolding bills so they didn't look new," Touvier said later. They stole a car. They held up a tax office in the middle of Paris. "I went to a priest," said Touvier, "who told me I had a right to take the state's money to feed my family. That was the psychology of the period." By family he meant Monique Berthet, a young woman with whom he was living. She worked in a bakery that Touvier was planning to rob. "It was an easy job," he said. "We'd have not only the money but the bread tickets," for rationing was still in force. But there was a police informer in Touvier's gang, and before he could hold up the bakery, he was arrested, in July 1947. By this time, Touvier had twice been tried in absentia for war crimes and twice been sentenced to death - in Lyons on Sept. 10, 1946, and in Chambery on March 4, 1947. Touvier knew that the Paris police would transfer him to Lyons, where his sentence would, in all likelihood, be carried out. On July 9, he escaped. Wandering in the streets of Paris, not knowing where to go, Touvier stopped at the first church he saw, Saint-Francois-Xavier, and told the parish priest he was a hunted man. The priest, Pierre Duben, was sympathetic. A few days later, Monique Berthet joined him and Father Duben married them, although they did not obtain a civil marriage license, and passed them on to a convent for shelter.[1]

Fugitive

Beginning in 1957, Monsignor Charles Duquaire, secretary to the Archbishop of Lyons, began gathering information and advocating a pardon for Paul Touvier.

By 1967, Touvier's death sentence was barred based on a 20-year statute of limitations. According to Morgan,

Touvier could now have surfaced, but preferred to stay in hiding, awaiting his hoped-for pardon. For the statute of limitations did not affect les peines accessoires, or secondary sentences, imposed by the law, which can include the loss of rights as a citizen, the confiscation of property and lifetime banishment from the area where the crimes were committed. For Touvier, les peines accessoires meant that he could not live with his wife and children in Chambery, which he considered home; he could not inherit property from his father; he could not legally marry his wife or give his children his name. He had gotten away with his life, but he was still a nonperson.[1]

In December 1969, Monsignor Duquaire's dossier, which included a five-hour taped interview with a fugitive Touvier, was handed over to the pardons commission. According to Morgan,

In January 1970, Jacques Delarue, an expert on the Occupation and a commissioner of the Police Judiciaire, a sort of French Federal Bureau of Investigation, was asked by the Minister of Justice to investigate the pardon request and talk to the people who had written testimonial letters. Now a youthful-looking 70 and living in a Paris suburb, Delarue recalls that Monsignor Duquaire came from Rome to see him and said, "You must understand that Touvier is one of the wounded who has been left on the battlefield." Delarue responded, "Monsignor, you have been duped. Touvier has blood on his hands." But, he said, Duquaire "wouldn't listen". He said, "I don't want to know what he did during the Occupation." Delarue's report concluded that a pardon for Touvier would provoke public outrage. In November 1971, however, to Delarue's consternation, Pompidou went ahead and granted the pardon, keeping the news out of the papers. Pompidou is said to have remarked: "This is an old story. I'll sign."[1]

President Pompidou's pardon caused a public outcry, especially among veterans of the French Resistance and the nation's Jewish community. On July 3, 1973, Georges Glaeser filed a complaint against Touvier in the Lyon Court, charging him with crimes against humanity. There was no statute of limitations for such charges. Glaeser accused Touvier of the 1944 massacre at Rillieux-la-Pape. After being indicted, Touvier disappeared again.

According to Morgan,

During the 10 years between the pardon and the indictment, while the suits filed by the victims' families moved through the courts, Touvier returned to the monastery circuit. Documents found by the gendarmes who later arrested him showed that he had stayed in more than 20 religious communities. While Touvier plugged into the remains of the old Catholic right, he also was aided by a number of credulous, apolitical priests. He would carefully tailor his story to suit his audience. To the unreconstructed old guard, he presented himself as the victim of a social order that persecuted him because he was a Catholic anti-Communist. His line was, "I was in the Milice to defend Christianity against Communism." To the others, he came across as a breast-beating, repentant sinner, hounded by the State and asking for compassion. So some of the priests who helped him were politically motivated; others acted from the belief in the right to asylum and the possibility of redemption. But once he was indicted for crimes against humanity, Touvier became an embarrassment to the Church, which was suddenly seen as the accomplice of a war criminal. The publicity was so damaging that the Diocese of Lyons released a statement saying that Monsignor Duquaire had been "acting on his own initiative."[1]

Years of legal maneuvering ensued until an arrest warrant for Touvier was issued on November 27, 1981.

Arrest and trial

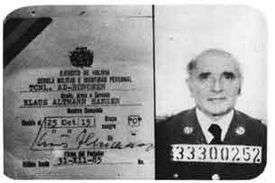

In 1988, examining magistrate Claude Grellier assigned 48-year-old Lieut. Col. Jean-Louis Recordon to track down and arrest Paul Touvier. After a series of wiretaps and raids on Traditionalist Catholic religious communities and sympathisers, Recordon was tipped off that Touvier was hiding in a Society of Saint Pius X Priory in Nice.

On May 24, 1989, Recordon's team served a search warrant on the Priory. According to Ted Morgan,

Shortly after 8 A.M., with gendarmes stationed around the priory walls, Recordon knocked and showed his search warrant. He bounded up the stairs to the second floor, where monks' rooms opened onto a long hall. He started opening doors, and he had not opened many when he saw, standing in the middle of a room in cotton pajamas, a short elderly man with a lined face and thinning gray-blond hair. "I suppose it's me you want," the man said. "I am Paul Touvier." From other rooms emerged his wife, in a bathrobe, and his two children, Pierre and Chantal, now 39 and 40. They could have lived normal lives under assumed names, but had chosen to follow their father into hiding.[1]

In response, the SSPX announced,

Despite the fact that most newspapers made a link between Mr. Touvier and the Society, there was in fact no connection. It is true he was taken prisoner at our priory, but he was merely let in by the prior as an act of charity to a homeless man. Since Archbishop Lefebvre's father died at the hands of the Nazis in a prison camp, that should be evidence enough that the Society does not and has not ever condoned the practices of the Nazis.[4]

Touvier retained the services of the monarchist lawyer Jacques Trémollet de Villers, who later became president of the Traditionalist Catholic organization Cité catholique.

Paul Touvier was granted provisional release in July 1991. His trial for crimes against humanity did not begin until March 17, 1994. A Traditionalist Catholic priest of the Society of Saint Pius X sat beside Touvier at the defense table, acting as his spiritual adviser. Touvier expressed remorse for his actions, saying, before the jury began deliberations, "I have never forgotten the victims of Rillieux. I think about them every day, every night."[5]

On April 20, a nine-person jury found him guilty.[6] Despite his attorney's promises to appeal, Touvier was sentenced to life imprisonment.[5]

In 1995, Pierre and Chantal Touvier appealed to French President Jacques Chirac, asking for their father's release for reasons of ill health. The appeal was rejected.

Death

On July 17, 1996, Paul Touvier died at age 81 of prostate cancer in Fresnes Prison, near Paris. Shortly before his death, Touvier was allowed to marry his wife Monique in a civil ceremony, allowing her to become his legal heir.[7]

A Tridentine Requiem Mass was offered for the repose of his soul by Father Philippe Laguérie at St Nicolas du Chardonnet, the Society of St. Pius X chapel, in Paris.

In popular culture

The Irish-Canadian novelist Brian Moore's 1995 novel, The Statement, is loosely based on Touvier's life. It was adapted as a film, also titled The Statement (2003), directed by Norman Jewison. Michael Caine appeared as Pierre Brossard, a character inspired by Touvier.

The 1989 efforts by French authorities to find and arrest Touvier are documented in an episode of the History Television series, Nazi Hunters, first broadcast November 1, 2010.[8]

Brel connection

For several years, the Belgian singer Jacques Brel worked with Touvier, apparently unaware of his identity.[9]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Morgan, Ted (October 1, 1989), L'Affaire Touvier: Opening Old Wounds, The New York Times, retrieved February 12, 2011

- 1 2 3 4 Biography of Paul Touvier, Centre d'Histoire de la Résistance et de la Déportation, Lyon, France. Retrieved February 13, 2011 (French)

- ↑ "Paul Touvier; Convicted of War Crimes", Los Angeles Times, July 19, 1996

- ↑ Angelus Press, June 1989

- 1 2 "Frenchman Gets Life Term for WWII Killings : War crimes: The Vichy regime's militia chief ordered the execution of seven Jews in 1944." Los Angeles Times, April 20, 1994

- ↑ Some Old Crimes Never Die, Los Angeles Times, April 24, 1994

- ↑ Obituary: Paul Touvier

- ↑ HistoryTelevision.ca

- ↑ Jacques Cordy, "Jacques Brel Berné par « Monsier Paul »" Le Soir, Brussels, Belgium. (March 25, 1994). Retrieved February 13, 2011 (French)

External links

- Simon Kitson, "Bousquet, Touvier and Papon: Three Vichy personalities" University of Portsmouth French History Interview series

- Resistance and Deportation History Centre

Resources

Brian Busby, Character Parts: Who's Really Who in CanLit (2003) - ISBN 0-676-97579-8