Peter Mollica

Peter Mollica (born 1941) is an American stained glass artist.

| Peter Mollica | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1941 Newton, Massachusetts |

| Nationality | American |

| Field | Artist, stained glass |

| Education | Apprenticeship, Somerville, MA 1964–68 |

| Books | Stained Glass Primer, 1971 Stained Glass Primer, Vol. 2, 1977 |

| Website | official website |

Biography

Peter Mollica received his formal training making traditional Gothic Style stained glass windows during an apprenticeship to the Chris Rufo Studio in Somerville, MA (1964-1968).[1] In 1968 he relocated to Berkeley, California and opened his own studio. In 1979 the studio moved to Oakland. He has fabricated windows for the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. and The Oakland Federal Building and both designed and fabricated works for west coast libraries, churches and homes. His free hanging glass panels have been widely exhibited and collected.[2] He is the author of Stained Glass Primer, an authoritative how-to guide to stained glass technique, used widely by hobbyists and professionals since first published in 1971.[3] Mollica has regularly taught design workshops in the San Francisco Bay Area, Mendocino, CA, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada and Nagano City, Japan.

Peter Mollica was a central figure, perhaps the earliest, of a generation of West Coast stained glass artists who emerged in the late 1960s and early ’70s. During his Massachusetts apprenticeship, Mollica was inspired by the contemporary German architectural glass he discovered when reading Robert Sowers’ Stained Glass: An Architectural Art.[4] At age 23 he committed to what would become a lifelong passion: stained glass. His success was such that Sowers included Mollica’s work in a later book.[5]

In 1975, after moving to the West Coast, Mollica studied in England with designers Ludwig Schaffrath and Patrick Reyntiens, then visited Germany to see first hand early 20th century windows of Johan Thorn Prikker and Heinrich Campendonk together with those of contemporary artists Ludwig Schaffrath, Wilhelm Buschulte, Johannes Schreiter and Georg Meistermann.[6]

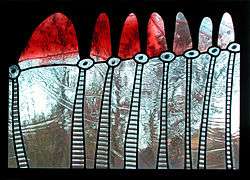

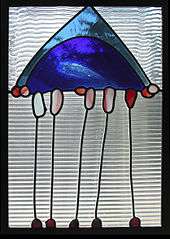

Mollica’s unique style is rooted in 20th Century German stained glass design. His works are generally based upon “a grid pattern” that is “interrupted by lyrical passages.”[7] Like German glass design, his lead lines play a graphic role, and he is inclined to restrict or eliminate color.[8] Mollica’s work, whether in public buildings or private residences, grows from the surrounding architecture making use of the colors, textures, ripples and bubbles in hand blown glass to enhance the full environment.[1] His public commissions are inclined to rely more heavily on “gridded structures,” whereas windows for private residences flow with more “flexible structure.”[7] Mollica says of his windows in buildings: “Stained glass should respect the intentions of the architect—whether the building has been designed as a meditative space or a container for exuberant celebration. It should also assist, in some aesthetic or spiritual way, the people who use it.”[9]

Mollica has also been part of a West Coast group of artists who designed and fabricated their own independent stained glass panels. Many of them worked closely with one another and often exhibited their work together during the 1970s and ’80s. In the introductory statement to the “New Stained Glass Exhibition” in which Mollica showed his work with fellow West Coast artists Robert Kehlmann, Sanford Barnett, Garth Edwards, Casey Lewis, Paul Marioni, Richard Posner, and Narcissus Quagliata, Kehlmann points out how the work of these artists has an affinity with twentieth century drawing and painting. In Mollica’s autonomous panels, as in those of the others, “the texture and relief of glass, lead and solder assume a significance” that is all but lost in a large window far away from the viewer’s eye.[10] Mollica’s panels, often whimsical and lighthearted, are inclined to be far more personal and expressive than his larger architectural works. “Throughout the ’80s, Mollica manipulated transparency in panels that interact ever more fluently with their visual surroundings.”[11]

Gallery

Peter Mollica, Untitled (1969), Private Collection, El Cerrito, CA |

Peter Mollica, Untitled (1993), Mollica Studio Archive |

Peter Mollica, Untitled (2011), Mollica Studio Archive |

Peter Mollica, Untitled (2006), Private Collection, Oakland, CA |

Peter Mollica, Untitled (2000), Mollica Studio Archive |

Peter Mollica, Untitled (2010), Mollica Studio Archive |

Notable commissions

- 1978 The Brentwood CA Public Library.

- 1978 The Christian Science Reading Room in Berkeley, CA

- 1978 St. Mary's College High School Chapel, Berkeley, CA.

- 1989 Eight windows for cloister of House of Hope Presbyterian Church in St. Paul, MN.

- 1995 Designed and fabricated 12 windows at St. Theresa Church in Oakland, CA.

- 1998 Clerestory and Bimah windows for Congregation Shir Hadash, Los Gatos, CA.

- 1999 Clerestory windows for University of Oregon Knight Law Center, Eugene, OR.

- 2000 St.Catherine of Siena Chapel windows at St. Rose Dominican Hospital, Henderson, NV.

- 2001 Entry and Library windows for Christ the King Catholic School (Pleasant Hill, California)

- 2002 Vestibule window for St. Theresa Church, Oakland, CA.

- 2002 Reading Room windows Hollywood Branch Library, Portland, OR.

- 2003 Northside Community Center, San Jose, CA.

- 2003 Clerestory windows, Dublin Public Library, Dublin, CA.

- 2004 Reading Room windows, Millbrae Public Library, Millbrae, CA.

- 2006 San Martín Chapel at St. Rose Dominican Hospital, Las Vegas, NV.

- Throughout his career Mollica has designed numerous windows for private residences in the San Francisco Bay Area and along the west coast.

Collaborations

- 1988 Fabricated two clerestory windows designed by Rowan LeCompte for the Washington National Cathedral, Washington, D.C.

- 1993 Fabricated 64 laminated glass panels designed by Ed Carpenter for the Oakland Federal Building, Oakland, CA.

- 2006 Fabricated a residence window designed by Robert Kehlmann, Stinson Beach, CA.

Notable exhibitions

- 1968 Judah Magnes Museum, “California Crafts Exhibit,” Berkeley, CA.

- 1969 “California Crafts,” Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, CA.

- 1969 “Peter Mollica/Stained Glass,” American Institute of Architects, Oakland, CA.

- 1972 “Peter Mollica/Stained Glass,” Richmond Art Center, Richmond, CA.

- 1974 “Peter Mollica & Paul Marioni,” Phillips-Allen Gallery, San Francisco, CA.

- 1974 “California Ceramics & Glass,” Oakland Museum, Oakland, CA. (catalog)

- 1976 “New Directions in Leaded Glass: Six Bay Area Artists,” Berkeley Arts Center, Berkeley, CA.

- 1978 “New Stained Glass,” Museum of Contemporary Crafts, NY and The Renwick Gallery of The Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. (catalog)

- 1979 “Das Bild in Glas,” Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt, Germany. (catalog)

- 1979 “New Glass,” Corning Museum of Glass, Corning, NY. Traveled to The Toledo Museum, Toledo, OH, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris, Seibu Museum, Tokyo, The Decorative, Applied and Folk Art Museum, Moscow and The Hermitage Museum, Leningrad. (catalog)

- 1982 Museum fur Zeitgenössische Glasmalerei, Langen, Germany.

- 1987 “Thirty Years of Glass, 1957-1987,” Corning Museum, Corning, NY

- 1988 “World Glass Now ’88,’ Hokkaido Museum of Modern Art, Sapporo, Japan (catalog)

- 1989 “History of American Glass,” Corning Museum, Corning, NY. Traveled as a cultural exchange with the USSR:

- 1994 “Bay Area Artists Working with Glass,” Cecile Moochnek Gallery, Berkeley, CA.

References

- 1 2 Otto B. Rigan and Charles Frizzell, New Glass, San Francisco Book Company, San Francisco, 1976.

- ↑ “50 Years of Studio Glass”, California Glass Exchange: www.californiastudioglass.org

- ↑ Peter Mollica, Charles Frizzell and Norm Fogel, Stained Glass Primer: The Basic Skills, 1971 and Stained Glass Primer: Advanced Skills & Annotated Bibliography, 1977, Mollica Stained Glass Press, Oakland, CA

- ↑ Robert Sowers, Stained Glass: An Architectural Art, Universe Books, Inc. New York, 1965

- ↑ Robert Sowers, The Language of Stained Glass, Timber Press, Forest Grove, Oregon 1981.

- ↑ RK Burleighfield House article, Glass Art

- 1 2 Lindsay Stamm Shapiro, “American Stained Glass Now,” Craft Horizons, February, 1978.

- ↑ Beverly Edna Johnson, “Graphics in Glass,” Los Angeles Times Home Magazine, September 14, 1975.

- ↑ Quote from Kate Baden Fuller's book: Contemporary Stained Glass Artists, 2006.

- ↑ New Stained Glass (catalog), The Museum of Contemporary Crafts of the American Crafts Council (1978).

- ↑ Geoffrey Wichert, “Whatever Happened to Stained Glass?,” Glass; The Urban Glass Quarterly, Spring 2002.

|