Philip Spratt

Philip Spratt (26 September 1902 – 8 March 1971) was a British writer and intellectual. Initially a communist sent by the British arm of the Communist International (Comintern), based in Moscow, to spread Communism in India, he subsequently became a friend and colleague of M.N. Roy, founder of the Communist parties in Mexico and India, and along with him became an anti-communist activist.[1]

He was among the first architects, and a founding-member of the Communist Party of India, and was among the chief accused in the Meerut Conspiracy Case; he was arrested on 20 March 1929 and imprisoned.[2][3]

As a result of his reading during his time in jail, and also his observation of political developments in Russia and Western Europe at the time, Philip Spratt renounced Communism in the early 1930s. After India gained independence from the British, he was among the lone voices – such as Sita Ram Goel – against the well-intentioned and fashionable leftist policies of Nehru and the Indian government.[4][5]

He was the Editor of MysIndia, a pro-American weekly, and later of Swarajya, a newspaper run by C. Rajagopalachari. He was also a prolific writer of books, articles and pamphlets on a variety of subjects, and translated books in French, German, Tamil, Sanskrit and Hindi, into English.

Early life

Philip Spratt was born in Camberwell on 26 September 1902 to Herbert Spratt, a schoolmaster, and Norah Spratt. He was one of five boys. His elder brother David Spratt, left boarding school to join the British army during World War I, and was killed at Passchendaele in 1917. Although raised a Baptist, Herbert Spratt later joined the Church of England. Philip Spratt's own rejection of religion came early on:

"By the age of 17 I had a fair knowledge of nineteenth-century physical science, and I read a little on my own in biology. On Sunday evenings after church I used to take a fast walk round the neighbourhood, and for some months on these walks I argued with myself about science and religion. I decided quite definitely that the religious theory of things was unsound. But I remember no 'conflict' or emotion over my rejection of religion. I kept it entirely to myself, and I still attended church, and continued to do so till I went to the university."[6]

University and early Communist activity

Philip Spratt got a university scholarship in 1921 for Downing College, Cambridge, to study Mathematics. He writes in his memoirs: "But I was in no mood to devote myself to my proper studies, or to associate with the dull dogs who stuck to theirs. I dabbled in literature and philosophy and psychology and anthropology." [7] He was awarded a First-class degree on completing the Mathematics tripos. He joined the Union Society, the University Labour Club and a private discussion society called the Heretics, of which Charles Kay Ogden was President; Frank P. Ramsey, I.A. Richards and Patrick Blackett, Baron Blackett often attended. Philip Spratt, Maurice Dobb, John Desmond Bernal, Ivor Montagu, the historian Allen Hutt, A.L Bacharach, Barnet Woolf and Michael Roberts (writer) comprised the tiny handful of Communist Party members at the university at that time. Spratt, Woolf and Roberts would sell the Worker's Weekly to railwaymen at the town railway station or canvass the working-class areas of Cambridge. Spratt worked, for a while, at the Labour Research Department in the Metropolitan Borough of Deptford, and was a member of the London University Labour Party.

In 1926, at the age of 24, he was asked by Clemens Dutt (the elder brother of Rajani Palme Dutt) to journey to India as a Comintern agent to organise the working of the then nascent Communist Party of India, and in particular to launch a Workers and Peasants' Party as a legal cover for their activities. He was expected to arrange for the infiltration of CPI members into the Congress party, trade unions and youth leagues to obtain leadership of them. Spratt was also asked to write a pamphlet on China, urging India to follow the example of the Kuomintang. He was accompanied to India by Ben Bradley and Lester Hutchinson.

Move to India

Spratt was arrested in 1927, on account of some cryptic letters written to and by him that were seized by the Police. He was, however, charged with sedition, on account of the pamphlet entitled India and China that he had written on Clemens Dutt's instructions. He was tried by jury and – the judge, Mr. Justice Fawcett, having summed up very leniently – they found in his favour.

Hansard records show that on 28 November 1927, Shapurji Saklatvala, the MP for Battersea North, questions Earl Winterton (then Under-Secretary of State for India in Baldwin's government) about the wrongful detention of Philip Spratt for six weeks prior to his trial.

- HC Deb 28 November 1927 vol 211 cc15-6

- § 32. Mr. SAKLATVALA asked the Under-Secretary of State for India if, in view of the fact that a Mr. Philip Spratt has recently been found not guilty by a jury in India of a charge of sedition in relation to the publication of a pamphlet entitled India and China, he will cause inquiries to be made as to the reason why he was in the first instance refused bail and thus kept in prison for six weeks prior to trial; and whether he will make representations for compensation to be paid to the said British national?

- § Earl WINTERTON It appears from the newspapers that bail was refused by Mr. Justice Davar in the High Court of Bombay, and it would not be proper to make inquiries as to the reasons for a decision which was within the competence of the Court. The answer to the second part of the question is in the negative.

- § Mr. SAKLATVALA Does the Noble Lord agree that this prosecution was launched by the Government and that the Judge of the High Court refused bail on certain representations which were made by the Government's prosecutor, which representations proved in the end to be untrue?

- § Earl WINTERTON The hon. Member is bringing a most serious charge against a Judge of the High Court, which I can-not accept for a moment. Judges of the High Court in India, as in this country, judge a question on its merits. Representations were doubtless made by prosecuting counsel, but the Judge is the sole interpreter as to whether they are correct, and I must respectfully decline to discuss on the Floor of the House the conduct of a Judge of the High Court.

- § Mr. SAKLATVALA Will the Noble Lord allow me to dispel his dramatic performance? Does the Noble Lord understand my question, which does not put any blame or comment or criticism on the Judge at all? My question is that the Judge, who gave a right decision upon the case presented to him by the Government prosecutor, afterwards, by his judgment, said it was a wrong presentation.

- § Earl WINTERTON I do not quite understand the hon. Member's question now. He has asked me whether I will cause inquiry to be made as to the reason why bail was refused. I have informed the hon. Member that I cannot do so because it would be committing a totally improper act, as criticising the action of the Judge. It rests solely with the Judge as to whether bail is granted or not.

- § Mr. SPEAKER Clearly, it is a matter for the Court of Justice.[8]

Meerut Conspiracy Trial

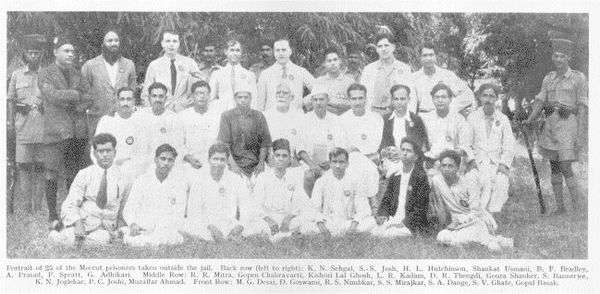

Middle Row: K.R. Mitra, Gopan Chakravarthy, Kishore Lal Ghosh, K.L. Kadam, D.R. Thengdi, Goura Shanker, S. Banerjee, K.N. Joglekar, P.C. Joshi, and Muzaffar Ahmed

Front Row: M.G. Desai, G. Goswami, R.S. Nimkar, S.S. Mirajkar, S.A. Dange, G.V. Ghate and Gopal Basak.

In March 1929, almost all the members of the Communist Party of India and about an equal number of trade unionists, congressmen and others who were working alongside them – 30 people in all – were arrested simultaneously in half a dozen different towns and taken to Meerut jail. Meerut Conspiracy Case

They were charged under Section 121A: conspiring to deprive the King Emperor of his sovereignty of British India. The body of conspirators was the Comintern and its associated organisations, and in particular the Indian party.

Spratt was sentenced to 12 years imprisonment, which on appeal, was reduced to 2; he was released from jail in October 1934. He discusses the psychology of imprisonment in an article which appeared in the Modern Review (Calcutta) in 1937.

It is his time in Meerut – Spratt records in his memoirs – that marked the beginning of his emotional turn away from communism: “When we had been in jail a year or two, the significance of the new Comintern line which we had accepted so uncomprehendingly at Calcutta began to show itself. It compelled the renovated party to split the central trade union body twice within two years, and to direct fierce criticism at the Congress, whose great Civil Disobedience campaigns made our activities look rather silly. We found fault with what was being done, but we did not direct our attack at the persons really responsible, viz. the Comintern authorities in Moscow… My own feelings were not of doubt or criticism but of boredom. I was closely involved in the preparation of the defence case, an immense and tedious job, and in the politics of the jail and the party outside. I gradually lost interest in all three, and became absorbed in reading and writing on other subjects… I have no doubt that here was the beginning of an emotional turn away from communism.” [9]

In December 1934 he was arrested again and interned under the emergency legislation passed to suppress Civil Disobedience. He spent 18 months in the Fort at Belgaum, and was released finally in June 1936.

During his time in Meerut, Spratt learnt to read Hindi and one of the first books he read was Atmakatha by Mahatma Gandhi. On doing so, he resolved to write a study of Gandhi and while in Belgaum wrote his book on the Mahatma entitled Gandhism: An Analysis. While in confinement, Spratt also wrote the foreword for Peshawar to Moscow: Leaves from an Indian Muhajireen's Diary by Shaukat Usmani.

Personal life

Soon after his release in 1934, he became engaged to Seetha, the grand-niece of Malayapuram Singaravelu Chettiar, who was a barrister and a founding member of the Communist Party in the south of India. Philip and Seetha married in 1939, and had four children: Herbert Mohan Spratt, Arjun Spratt, Radha Norah Spratt and Robert Spratt.

Post-Meerut life in India

Spratt began to write strongly in criticism of Soviet policy after the Russian invasion of Finland in 1939. In 1943, he joined M. N. Roy’s Radical Democratic Party, and remained a fairly active member until the party ceased to exist in 1948. In 1951, Spratt became secretary of the newly formed Indian Congress for Cultural Freedom, and a frequent contributor to its bulletin, Freedom First. He settled in Bangalore, and was the Chief Editor of a pro-American and pro-Capitalist weekly named MysIndia, until 1964.[10] In its columns, he criticised the policies of the government which he believed, 'treated the entrepreneur as a criminal who has dared to use his brains independently of the state to create wealth and give employment'. He further believed that the result would be 'the smothering of free enterprise, a famine of consumer goods, and the tying down of millions of workers to soul deadening techniques'.[10]

Spratt believed that the Kashmir valley should be granted independence. In 1952, he stated that India must abandon its claim to the valley and allow the National Conference leader Sheikh Abdullah to 'dream of independence'. It should withdraw its armies and write off its loans to the state government.[11] He stated:[11]

"Let Kashmir go ahead, alone and adventurously, in her explorations of a secular state. We shall watch the act of faith with due sympathy but at a safe distance, our honour, our resources and our future free from the enervating entaglements which write a lie in our soul."

He argued that Indian policy was based on a 'mistaken belief in the one-nation theory and greed to own the beautiful and strategic valley of Srinagar'.[11] He further stated that the costs of this policy, present and future, were incalculable, and that rather than give Kashmir special privileges and create resentment elsewhere in India, it was best to let the state secede.[11]

Spratt later moved to Madras, and edited the Swarajya, which was a newspaper run by C. Rajagopalachari, and a mouthpiece of the Swatantra Party. During these years he also wrote several books on diverse subjects, numerous pamphlets and also translated books from French, German, Tamil, Sanskrit and Hindi, into English. He died of cancer on 8 March 1971, in Madras.

Citations

- ↑ M N Roy Mainstream, Vol XLV, No 35.

- ↑ "Working Class Movement Library" Meerut Conspiracy Trial

- ↑ ROLE OF THE COMMUNISTS 60 Years of Our Independence and the Left: Some Thoughts – Jyoti Basu, Communist Party of India official website."We should remember the contribution of communists Rajani Palme Dutt (RPD), Clemens Dutt, Philip Spratt and Ben Bradley."

- ↑ Renounced communism.. Jawaharlal Nehru:A Biography, by Sankar Ghose, Allied Publishers, 1993, ISBN 81-7023-369-0. page 280.

- ↑ Foreword by Philip Spratt of the Sita Ram Goel's Genesis and Growth of Nehruism.

- ↑ Philip Spratt. Blowing Up India: Reminiscences and Reflections of a Comintern Emissary. Calcutta: Prachi Prakashan, 1955. p. 8

- ↑ Philip Spratt. Blowing Up India: Reminiscences and Reflections of a Comintern Emissary. Calcutta: Prachi Prakashan, 1955. p. 10

- ↑ MR. PHILIP SPRATT (PROSECUTION)

- ↑ Philip Spratt. Blowing Up India: Reminiscences and Reflections of a Comintern Emissary. Calcutta: Prachi Prakashan, 1955. p. 53-54

- 1 2 Guha 2008, pp. 692–693

- 1 2 3 4 Guha 2008, pp. 259–260

References

- Guha, Ramachandra (2008). India After Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy. Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-330-39611-0.

Further reading

- Foreword by Philip Spratt New Orientation: Lectures Delivered at the Political Study Camp Held at Dehra Dun from 8 to 18 May 1946.Calcutta, Renaissance Publishers. 1946.