Picket (punishment)

The picket, picquet or piquet was a form of military punishment in vogue in the 16th and 17th centuries in Europe. It consisted of the offender being forced to stand on the narrow flat top of a peg for a period of time. The punishment died out in the 18th century and was so unfamiliar by 1800 that when the then governor of Trinidad, Sir Thomas Picton, ordered Luisa Calderon, a woman of European and African ancestry to be so punished, he was accused by public opinion in England of inflicting a torture akin to impalement. It was thought erroneously that the prisoner was forced to stand on the head of a pointed stake, and this error was repeated in the New English Dictionary.[1][2]

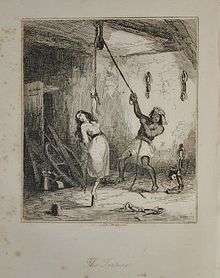

The punishment required placing a wooden peg (for the sort used for tents or for a line for cavalry horses — "picket" etc. were originally alternative names for such pegs) in the ground with the exposed end facing upward. The malefactor was typically a private soldier who had disobeyed orders. One wrist was suspended from a tree by a rope, while the sole or heel of the opposite bare foot was balanced atop the peg, a piece of wood about four inches long by two inches wide and rounded at the top to about half an inch to meet the legal requirements. The top of the peg was narrow enough to cause considerable discomfort, but not sharp enough to draw blood.[2] To relieve pressure upon a foot, the prisoner relegated all his weight to the wrist, which could only be relieved by shifting weight back onto the other foot.

The procedure could be continued for a few hours, to as much as a day or two. The punishment generally did not cause lasting physical harm.[2] A much more severe and physically damaging suspension torture is known as Strappado.

Notes

- ↑ Chisholm 1911, p. 583.

- 1 2 3 Kissoon 2008.

References

- Kissoon, Freddie (19 July 2008). "The torture of Louisa Calderon". Trinidad and Tobago's NewsDay.

Attribution:

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Picket". Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 584.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Picket". Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 584.