Pit of despair

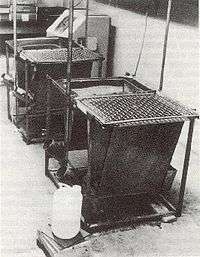

The pit of despair was a name used by American comparative psychologist Harry Harlow for a device he designed, technically called a vertical chamber apparatus, that he used in experiments on rhesus macaque monkeys at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the 1970s.[1] The aim of the research was to produce an animal model of clinical depression. Researcher Stephen Suomi described the device as "little more than a stainless-steel trough with sides that sloped to a rounded bottom":

A 3/8 in. wire mesh floor 1 in. above the bottom of the chamber allowed waste material to drop through the drain and out of holes drilled in the stainless-steel. The chamber was equipped with a food box and a water-bottle holder, and was covered with a pyramid top [removed in the accompanying photograph], designed to discourage incarcerated subjects from hanging from the upper part of the chamber.[2]

Harlow had already placed newly born monkeys in isolation chambers for up to one year. With the pit of despair, he placed monkeys between three months and three years old in the chamber alone, after they had bonded with their mothers, for up to ten weeks.[3] Within a few days, they had stopped moving about and remained huddled in a corner.

Background

Much of Harlow's scientific career was spent studying maternal bonding, what he described as the "nature of love". These experiments involved rearing newborn "total isolates" and monkeys with surrogate mothers, ranging from toweling-covered cones to a machine that modeled abusive mothers by assaulting the baby monkeys with cold air or spikes.[5] The point of the experiments was to pinpoint the basis of the mother-child relationship, namely whether the infant primarily sought food or affection. Harlow concluded it was the latter.

In 1971, Harlow's wife died of cancer and he began to suffer from depression. He was treated and returned to work but, as Lauren Slater writes, his colleagues noticed a difference in his demeanor.[6] He abandoned his research into maternal attachment and developed an interest in isolation and depression.

Harlow's first experiments involved isolating a monkey in a cage surrounded by steel walls with a small one-way mirror, so the experimenters could look in, but the monkey could not look out. The only connection the monkey had with the world was when the experimenters' hands changed his bedding or delivered fresh water and food. Baby monkeys were placed in these boxes soon after birth; four were left for 30 days, four for six months, and four for a year.

After 30 days, the "total isolates", as they were called, were found to be "enormously disturbed". After being isolated for a year, they barely moved, did not explore or play, and were incapable of having sexual relations. When placed with other monkeys for a daily play session, they were badly bullied. Two of them refused to eat and starved themselves to death.[7]

Harlow also wanted to test how isolation would affect parenting skills, but the isolates were unable to mate. Artificial insemination had not then been developed; instead, Harlow devised what he called a "rape rack", to which the female isolates were tied in normal monkey mating posture. He found that, just as they were incapable of having sexual relations, they were also unable to parent their offspring, either abusing or neglecting them. "Not even in our most devious dreams could we have designed a surrogate as evil as these real monkey mothers were", he wrote.[8] Having no social experience themselves, they were incapable of appropriate social interaction. One mother held her baby's face to the floor and chewed off his feet and fingers. Another crushed her baby's head. Most of them simply ignored their offspring.[8]

These experiments showed Harlow what total and partial isolation did to developing monkeys, but he felt he had not captured the essence of depression, which he believed was characterized by feelings of loneliness, helplessness, and a sense of being trapped, or being "sunk in a well of despair", he said.[8]

Vertical chamber apparatus

The technical name for the new depression chamber was "vertical chamber apparatus", though Harlow himself insisted on calling it the "pit of despair". He had at first wanted to call it the "dungeon of despair", and also used terms like "well of despair", and "well of loneliness". Blum writes that his colleagues tried to persuade him not to use such descriptive terms, that a less visual name would be easier, politically speaking. Gene Sackett of the University of Washington in Seattle, one of Harlow's doctoral students who went on to conduct additional deprivation studies, said, "He first wanted to call it a dungeon of despair. Can you imagine the reaction to that?"[9]

Most of the monkeys placed inside it were at least three months old and had already bonded with others. The point of the experiment was to break those bonds in order to create the symptoms of depression. The chamber was a small, metal, inverted pyramid, with slippery sides, slanting down to a point. The monkey was placed in the point. The opening was covered with mesh. The monkeys would spend the first day or two trying to climb up the slippery sides. After a few days, they gave up. Harlow wrote, "most subjects typically assume a hunched position in a corner of the bottom of the apparatus. One might presume at this point that they find their situation to be hopeless."[10] Stephen J. Suomi, another of Harlow's doctoral students, placed some monkeys in the chamber in 1970 for his PhD. He wrote that he could find no monkey who had any defense against it. Even the happiest monkeys came out damaged. He concluded that even a happy, normal childhood was no defense against depression.

The experiments delivered what science writer Deborah Blum has called "common sense results", namely, that monkeys, normally very social animals in nature, emerge from isolation badly damaged, and that some recover while others do not.[11]

Reaction

The experiments were condemned, both at the time and later, from within the scientific community and elsewhere in academia. In 1974, American literary critic Wayne C. Booth wrote that, "Harry Harlow and his colleagues go on torturing their nonhuman primates decade after decade, invariably proving what we all knew in advance—that social creatures can be destroyed by destroying their social ties." He writes that Harlow made no mention of the criticism of the morality of his work.[12]

Charles Snowdon, a junior member of the faculty at the time, who became head of psychology at Wisconsin, said that Harlow had himself been very depressed by his wife's cancer. Snowdon was appalled by the design of the vertical chambers. He asked Suomi why they were using them, and Harlow replied, "Because that's how it feels when you're depressed."[13] Leonard Rosenblum, who studied under Harlow, told Lauren Slater that Harlow enjoyed using shocking terms for his apparatus because "he always wanted to get a rise out of people." [14]

Another of Harlow's students, William Mason, who also conducted deprivation experiments elsewhere,[15] said that Harlow "kept this going to the point where it was clear to many people that the work was really violating ordinary sensibilities, that anybody with respect for life or people would find this offensive. It's as if he sat down and said, 'I'm only going to be around another ten years. What I'd like to do, then, is leave a great big mess behind.' If that was his aim, he did a perfect job."[16]

See also

- Animal testing

- Britches (monkey)

- Silver Spring monkeys

- Flowerpot technique, a method of sleep deprivation in laboratory animals

- Unnecessary Fuss (video showing brain damage experiments on baboons)

- Refrigerator mother theory

Notes

- ↑ Blum 1994, p. 95, Blum 2002, pp. 218-219. Blum 1994, p. 95: "... the most controversial experiment to come out of the Wisconsin laboratory, a device that Harlow insisted on calling the "pit of despair."

- ↑ Suomi 1971, p. 33.

- ↑ McKinney, Suomi, and Harlow 1972.

- ↑ Stephens 1986, p. 17.

- ↑ Slater, Lauren. Opening Skinner's box: great psychological experiments of the twentieth century, W. W. Norton & Company, 2005, ISBN 0-393-32655-1, pp.136-40.

- ↑ Slater 2005, pp. 251-2

- ↑ Blum 2002, p. 216.

- 1 2 3 Blum 2002, p. 217.

- ↑ Blum 1994, p. 95; Blum 2002, p. 219.

- ↑ Blum 1994, p. 218.

- ↑ Blum 2002, p. 225.

- ↑ Booth, Wayne C. Modern Dogma and the Rhetoric of Assent, Volume 5, of University of Notre Dame, Ward-Phillips lectures in English language and literature, University of Chicago Press, 1974, p. 114. Booth is explicitly discussing this experiment. His next sentence is, "His most recent outrage consists of placing monkeys in "solitary" for twenty days—what he calls a "vertical chamber apparatus ... designed on an intuitive basis" to produce "a state of helplessness and hopelessness, sunken in a well of despair."

- ↑ Blum 2002, p. 220.

- ↑ Slater 2005, p. 148

- ↑ Capitanio and Mason 2000.

- ↑ Blum 1994, p. 96.

References

- Blum, Deborah (1994). The Monkey Wars. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-510109-X.

- Blum, Deborah (2002). Love at Goon Park: Harry Harlow and the Science of Affection. Perseus Publishing. ISBN 0-7382-0278-9.

- Capitanio J.P.; Mason W.A. (June 2000). "Cognitive style: problem solving by rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) reared with living or inanimate substitute mothers". J Comp Psychol. 114 (2): 115–25. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.114.2.115. PMID 10890583.

- McKinney W.T. Jr.; Suomi S.J.; Harlow H.F. (March 1972). "Vertical-chamber confinement of juvenile-age rhesus monkeys. A study in experimental psychopathology". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 26 (3): 223–8. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750210031006. PMID 4621802.

- Stephens, M.L. Maternal Deprivation Experiments in Psychology: A Critique of Animal Models. AAVS, NAVS, NEAVS, 1986.

- Suomi, Stephen John. "Experimental Production of Depressive Behavior in Young Rhesus Monkeys: Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Psychology) at the University of Wisconsin," University of Wisconsin, 1971, p. 33.