Adipocyte

| Adipocyte | |

|---|---|

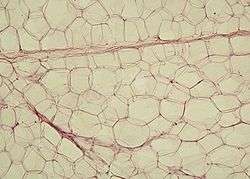

Yellow adipose tissue in paraffin section | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | adipocytus |

| Code | TH H2.00.03.0.01005 |

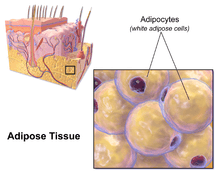

Adipocytes, also known as lipocytes and fat cells, are the cells that primarily compose adipose tissue, specialized in storing energy as fat.[1]

There are two types of adipose tissue, white adipose tissue (WAT) and brown adipose tissue (BAT), which are also known as white fat and brown fat, respectively, and comprise two types of fat cells. Most recently, the presence of beige adipocytes with a gene expression pattern distinct from either white or brown adipocytes has been described.

White fat cells (unilocular cells)

White fat cells or monovacuolar cells contain a large lipid droplet surrounded by a layer of cytoplasm. The nucleus is flattened and located on the periphery. A typical fat cell is 0.1 mm in diameter with some being twice that size and others half that size. The fat stored is in a semi-liquid state, and is composed primarily of triglycerides and cholesteryl ester. White fat cells secrete many proteins acting as adipokines such as resistin, adiponectin, leptin and apelin. An average human adult has 30 billion fat cells with a weight of 30 lbs or 13.5 kg. If excess weight is gained as an adult, fat cells increase in size about fourfold before dividing and increasing the absolute number of fat cells present.[2]

Brown fat cells (multilocular cells)

Brown fat cells or plurivacuolar cells are polygonal in shape. Unlike white fat cells, these cells have considerable cytoplasm, with lipid droplets scattered throughout. The nucleus is round, and, although eccentrically located, it is not in the periphery of the cell. The brown color comes from the large quantity of mitochondria. Brown fat, also known as "baby fat," is used to generate heat.

Lineage

Pre-adipocytes are undifferentiated fibroblasts that can be stimulated to form adipocytes. Recent studies shed light into potential molecular mechanisms in the fate determination of pre-adipocytes although the exact lineage of adipocyte is still unclear.[3][4] The variation of body fat distribution resulting from normal growth is influenced by nutritional and hormonal status in dependence on intrinsic differences in cells found in each adipose depot.[5]

Mesenchymal stem cells can differentiate into adipocytes, connective tissue, muscle or bone.[1]

The term "lipoblast" is used to describe the precursor of the adult cell. The term "lipoblastoma" is used to describe a tumor of this cell type.[6]

Cell turnover

Even after marked weight loss, the body never loses adipocytes.As a rule, to facilitate changes in weight, the adipocytes in the body merely gain or lose fat content. However, if the adipocytes in the body reach their maximum capacity of fat, they may replicate to allow additional fat storage.

Adult rats of various strains became obese when they were fed a highly palatable diet for several months. Analysis of their adipose tissue morphology revealed increases in both adipocyte size and number in most depots. Reintroduction of an ordinary chow diet to such animals precipitated a period of weight loss during which only mean adipocyte size returned to normal. Adipocyte number remained at the elevated level achieved during the period of weight gain.[7]

In some reports and textbooks, the number of adipocytes can increase in childhood and adolescence, though the amount is usually constant in adults. Interestingly, individuals who become obese as adults, rather than as adolescents, have no more adipocytes than they had before.[8]

People who have been fat since childhood generally have an inflated number of fat cells. People who become fat as adults may have no more fat cells than their lean peers, but their fat cells are larger. In general, people with an excess of fat cells find it harder to lose weight and keep it off than the obese who simply have enlarged fat cells.[9]

According to research by Tchoukalova et al., 2010, body fat cells could have regional responses to the overfeeding that was studied in adult subjects. In the upper body, an increase of adipocyte size correlated with upper-body fat gain; however, the number of fat cells was not significantly changed. In contrast to the upper body fat cell response, the number of lower-body adipocytes did significantly increase during the course of experiment. Notably, there was no change in the size of the lower-body adipocytes.[10]

Approximately 10% of fat cells are renewed annually at all adult ages and levels of body mass index without a significant increase in the overall number of adipocytes in adulthood.[8]

Adipocyte adaptation

Obesity is characterized by the expansion of fat mass, through adipocyte size increase (hypertrophy) and, to a lesser extent, cell proliferation (hyperplasia).[11] In the fat cells of obese individuals, there is increased production of metabolism modulators, such as glycerol, hormones, and pro-inflammatory cytokines, leading to the development of insulin resistance.[12]

Fat production in adipocytes is strongly stimulated by insulin. By controlling the activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase and the acetyl-CoA carboxylase enzymes, insulin promotes unsaturated fatty acid synthesis. It also promotes glucose uptake and induces SREBF1, which activates the transcription of genes that stimulate lipogenesis.[13]

SREBF1 (sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factor 1) is a transcription factor synthesized as an inactive precursor protein inserted into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane by two membrane-spanning helices. Also anchored in the ER membrane is SCAP (SREBF-cleavage activating protein), which binds SREBF1. The SREBF1-SCAP complex is retained in the ER membrane by INSIG1 (insulin-induced gene 1 protein). When sterol levels are depleted, INSIG1 releases SCAP and the SREBF1-SCAP complex can be sorted into COPII-coated transport vesicles that are exported to the Golgi. In the Golgi, SREBF1 is cleaved and released as a transcriptionally active mature protein. It is then free to translocate to the nucleus and activate the expression of its target genes.

Clinical studies have repeatedly shown that even though insulin resistance is usually associated with obesity, the membrane phospholipids of the adipocytes of obese patients generally still show an increased degree of fatty acid unsaturation.[15] This seems to point to an adaptive mechanism that allows the adipocyte to maintain its functionality, despite the increased storage demands associated with obesity and insulin resistance.

A study conducted in 2013[15] found that, while INSIG1 and SREBF1 mRNA expression was decreased in the adipose tissue of obese mice and humans, the amount of active SREBF1 was increased in comparison with normal mice and non-obese patients. This downregulation of INSIG1 expression combined with the increase of mature SREBF1 was also correlated with the maintenance of SREBF1-target gene expression. Hence, it appears that, by downregulating INSIG1, there is a resetting of the INSIG1/SREBF1 loop, allowing for the maintenance of active SREBF1 levels. This seems to help compensate for the anti-lipogenic effects of insulin resistance and thus preserve adipocyte fat storage abilities and availability of appropriate levels of fatty acid unsaturation in face of the nutritional pressures of obesity.

Endocrine functions

Adipocytes can synthesize estrogens from androgens,[16] potentially being the reason why being underweight or overweight are risk factors for infertility.[17] Additionally, adipocytes are responsible for the production of the hormone leptin. Leptin is important in regulation of appetite and acts as a satiety factor.[18]

References

- 1 2 Birbrair, Alexander; Zhang, Tan; Wang, Zhong-Min; Messi, Maria Laura; Enikolopov, Grigori N.; Mintz, Akiva; Delbono, Osvaldo (2013-03-21). "Role of Pericytes in Skeletal Muscle Regeneration and Fat Accumulation". Stem Cells and Development. 22 (16): 2298–2314. doi:10.1089/scd.2012.0647. ISSN 1547-3287. PMC 3730538

. PMID 23517218.

. PMID 23517218. - ↑ Pool, Robert (2001). Fat: fighting the obesity epidemic. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511853-7.Template:Incorrect citation

- ↑ "Scientists closer to finding what causes the birth of a fat cell". ScienceDaily.

- ↑ Coskun, Huseyin; Summerfield, Taryn LS; Kniss, Douglas A; Friedman, Avner (2010). "Mathematical modeling of preadipocyte fate determination". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 265 (1): 87–94. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.03.047. PMID 20385145..

- ↑ Fried SK, Lee MJ, Karastergiou K (2015). "Shaping fat distribution: New insights into the molecular determinants of depot- and sex-dependent adipose biology". Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) (Review). 23 (7): 1345–52. doi:10.1002/oby.21133. PMC 4687449

. PMID 26054752.

. PMID 26054752. - ↑ Hong, Ran; Choi, Dong-Youl; Do, Nam-Yong; Lim, Sung-Chul (2008). "Fine-needle aspiration cytology of a lipoblastoma: A case report". Diagnostic Cytopathology. 36 (7): 508–11. doi:10.1002/dc.20826. PMID 18528880.

- ↑ Faust, IM.; Johnson, PR; Stern, JR; Hirsch, J (1978). "Diet-induced adipocyte number increase in adult rats: a new model of obesity". Am J Physiol. 235 (3): 279–96. PMID 696822.

- 1 2 Spalding, K. L.; Arner, E.; Westermark, P. L. O.; Bernard, S.; Buchholz, B. A.; Bergmann, O.; Blomqvist, L.; Hoffstedt, J.; Näslund, E.; Britton, T.; Concha, H.; Hassan, M.; Rydén, M.; Frisén, J.; Arner, P. (2008). "Dynamics of fat cell turnover in humans". Nature. 453 (7196): 783–787. doi:10.1038/nature06902. PMID 18454136.

- ↑ Pool, Robert (2001). Fat: fighting the obesity epidemic. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-19-511853-7.

- ↑ Tchoukalova, YD.; Votruba, SB; Tchkonia, T.; Giorgadze, N.; Kirkland, JL.; Jensen, MD. (2010). "Regional differences in cellular mechanisms of adipose tissue gain with overfeeding". PNAS. 107 (42): 18226–31. doi:10.1073/pnas.1005259107. PMC 2964201

. PMID 20921416.

. PMID 20921416. - ↑ Blüher, M (2009). "Adipose Tissue Dysfunction in Obesity". Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 117 (6): 241–50. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1192044. PMID 19358089.

- ↑ Kahn, SE; Hull, RL; Utzschneider, KM (2006). "Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes". Nature. 444 (7121): 840–46. doi:10.1038/nature05482. PMID 17167471.

- ↑ Kahn, BB; Flier, JS (2000). "Obesity and insulin resistance.". J Clin Invest. 106 (4): 473–81. doi:10.1172/JCI10842. PMC 380258

. PMID 10953022.

. PMID 10953022. - ↑ Rawson, RB (2003). "The SREBP pathway—insights from Insigs and insects". Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 4 (8): 631–40. doi:10.1038/nrm1174. PMID 12923525.

- 1 2 Carobbio, S; Hagen, RM; Lelliot, CJ; Slawik, M; Medina-Gomez, G; Tan, CY (2013). "Adaptive changes of the Insig1/SREBP1/SCD1 set point help adipose tissue to cope with increased storage demands of obesity". Diabetes. 62 (11): 3697–708. doi:10.2337/db12-1748. PMID 23919961.

- ↑ Nelson, Linda R.; Bulun, Serdar E. (2001). "Estrogen production and action☆". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 45 (3): S116–24. doi:10.1067/mjd.2001.117432. PMID 11511861.

- ↑ http://www.protectyourfertility.com/femalerisks.html Archived September 22, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. FERTILITY FACT > Female Risks By the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). Retrieved on Jan 4, 2009

- ↑ Klok, M.D.; Jakobsdottir, S.; Drent, M.L. (2006). "The role of leptin and ghrelin in the regulation of food intake and body weight in humans: a review". The International Association for the Study of Obesity. obesity reviews. 8 (1): 12–34. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00270.x. PMID 17212793.

External links

- Histology image: 08201loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University – "Connective Tissue: unilocular (white) adipocytes "

- Histology image: 04901lob – Histology Learning System at Boston University – "Connective Tissue: multilocular (brown) adipocytes"