Private currency

A private currency is a currency issued by a private organization, be it a commercial business or a nonprofit enterprise. It is often contrasted with fiat currency issued by governments or central banks. In many countries, the issuance of private paper currencies is severely restricted by law.

Today, there are over four-thousand privately issued currencies in more than 35 countries. These include commercial trade exchanges that use barter credits as units of exchange, private gold and silver exchanges, local paper money, computerized systems of credits and debits, and digital currencies in circulation, such as digital gold currency.

History

United States

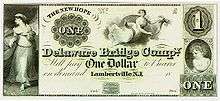

In the United States, the Free Banking Era lasted between 1837 and 1866, when almost anyone could issue paper money. States, municipalities, private banks, railroad and construction companies, stores, restaurants, churches and individuals printed an estimated 8,000 different types of money by 1860. If an issuer went bankrupt, closed, left town, or otherwise went out of business the note would be worthless. Such organizations earned the nickname of "wildcat banks" for a reputation of unreliability; they were often situated in remote, unpopulated locales said to be inhabited more by wildcats than by people. The National Bank Act of 1863 ended the "wildcat bank" period.

Ithaca hours

Since 1991, residents of and around the city of Ithaca in Western New York State have been using a private currency in which participating workers either earn or purchase Ithaca Hours, which may be used to buy goods and services locally. The system has been ruled legal provided all Hours-derived revenues are reported to the IRS as income.

BerkShares

BerkShares is a local currency that circulates in The Berkshires region of Massachusetts. It was launched on September 29, 2006 by BerkShares Inc., with research and development assistance from the E. F. Schumacher Society. The BerkShares website lists over 370 businesses in Berkshire County that accept the currency. In 30 months, 2.2 million BerkShares have been issued from 12 branch offices of five local banks.

United States Private Dollars

In 2007, Angel Cruz, founder of The United Cities Corporation (TUC), announced he was establishing an alternative "asset based" currency named "United States Private Dollars".[1] Cruz claimed his "United States Private Dollars" were "backed by the total net worth of the assets of its members" and had printed $6,127,379,895 worth of the private currency.[2] According to a press release, these assets were $357,170,993,418.[3] The currency featured the slogan "In Jehovah We Trust".[4]

Several of Cruz's employees stated that they had been promised a 30-year contract, a new car, health insurance and payment of their debts. The workers received compensation in the form of checks from United Cities. Those checks were rejected as fraudulent by local banks after the employees deposited them because they lacked standard routing numbers.[5]

The U.S. Treasury Department's Office of the Comptroller of the Currency issued an alert warning banks that United Cities' checks were "valueless instruments" and should not be cashed.[4]

On July 8, 2007, Cruz attempted to evict employees of a Palmetto Bay, Florida branch of the Bank of America. He was accompanied by 30 of his followers, 10 of whom were dressed as armed guards, and he presented a "court order" supposedly issued by "The United Cities Private Court." The "court order" referenced a pending $15.25 billion lawsuit against the Bank of America filed by Cruz in Miami-Dade County Court the month before. Cruz had claimed the bank had wronged him because an Orlando branch of Bank of America refused to cash $14.3 million in United Cities "bank drafts."[6]

On August 6, 2008, Cruz was indicted by a Federal grand jury in Florida on one count of conspiracy to defraud the United States under 18 U.S.C. § 1344 and 18 U.S.C. § 371 and six counts of bank fraud under 18 U.S.C. § 1344 and 18 U.S.C. § 2 in connection with his dealings with Bank of America with the United Cities bank drafts.[7] If convicted, Cruz would face a maximum possible sentence of up to 185 years in federal prison.[8]

As of late October 2010, the Assistant United States Attorney in Orlando, Florida filed a report with the U.S. District Court to the effect that Angel Cruz was still a fugitive, and that the United States Secret Service was continuing its efforts to apprehend Cruz.[9] A co-defendant in the case, Harry William Marrero, was sentenced on September 1, 2009 to eight years and one month in prison.[10] Marrero is incarcerated at the United States Penitentiary at Atlanta, Georgia, and with time off for good behavior would be scheduled for release on September 7, 2015.[11]

Liberty Dollars

The Liberty Dollar was a commodity-backed private currency created by Bernard von NotHaus and issued between 1998 and 2009, when von NotHaus and others were indicted on federal charges related to its issue. In 2011 von NotHaus was pronounced guilty of "making, possessing, and selling his own currency".[12][13]

In other countries

In Australia, the Bank Notes Tax Act of 1910 practically shut down the circulation of private currencies by imposing a prohibitive tax on the practice. It was later repealed and a fine imposed for private currencies (Commonwealth Bank Act 1945).

Now, s44(1) of the Reserve Bank Act 1959[14] prohibits this practice. In 1976, Wickrema Weerasooria published an article which suggested that the issuing of bank cheques violated this section, though some banks responded that since bank cheques were printed with the words "not negotiable" on them, the cheques were not intended for circulation and thus did not violate the statute.[15] Many other nations have similar such policies to eliminate private sector competition.

One example of a currency that lost government support but retained use in a community is the Iraqi Swiss dinar.

England has had the Totnes pound since it was launched by Transition Towns Totnes Economics and Livelihoods group in March 2007; A Totnes Pound is equal to one pound sterling and is backed by sterling held in a bank account. As at September 2008, about 70 businesses in Totnes were accepting the Totnes Pound. Other local currencies launched since then include the Lewes Pound (2008), the Brixton Pound (2009),[16] the Stroud Pound (2009)[17] and the Bristol Pound, which also allows for electronic payments [18]

Austria had the Wörgl Experiment from July 1932 to September 1933.

Bavaria, Germany, has had the Chiemgauer since 2003. As of 2011 there were over 550,000 in circulation[18]

Since starting in 2006, the "City Initiative Karlsruhe" has issued the Karlsruher which has no nominal value. Every coin has the value of 50 Eurocents and is primarily used in parking garages. As of 2009, 120 companies in Karlsruhe accept the Karlsruher and usually grant a discount when paid with it.[19]

In Hong Kong, although the government issues currency, bank issued private currency is the dominant medium of exchange. Most automated teller machines dispense private Hong Kong bank notes.[20]

In Canada, private currencies cannot be referred to as being legal tender (e.g. Calgary Dollar and Toronto dollar), or use alternate names like coupon or bucks (such as Canadian Tire money and Pioneer Energy's Bonus Bucks).

In August 2013, the German Finance Ministry characterized Bitcoin as a unit of account,[21][22] usable in multilateral clearing circles and subject to capital gains tax if held less than one year.[22]

In Thailand, lack of existing law leads many to believe Bitcoin is banned.[23]

Cryptocurrencies

A cryptocurrency is a form of digital currency where cryptography to secure the transactions and to control the creation of additional units of the currency.[24] The cryptographic systems used allow for decentralisation; a decentralised cryptocurrency is fiat money but one without a central banking system.

Bitcoin

In terms of total market value, Bitcoin is the largest cryptocurrency.[25]

On 6 August 2013, Federal Judge Amos Mazzant of the Eastern District of Texas of the Fifth Circuit ruled that bitcoins are "a currency or a form of money" (specifically securities as defined by Federal Securities Laws), and as such were subject to the court's jurisdiction,[26][27] and Germany's Finance Ministry subsumed Bitcoins under the term "unit of account"—a financial instrument—though not as e-money or a functional currency, a classification nonetheless having legal and tax implications.[21]

Currency backing

Today many private currencies are backed by a commodity to increase asset security and nullify inflation, which can be caused by an issuer increasing money supply. For a currency to be said to be backed by something, it must be redeemable for a specific amount of that which backs it. Some use established and historic forms of money, such as silver or gold, as in the case of digital gold currencies or the Liberty dollar.

It is possible for privately issued money to be backed by any commodity, although some people argue that perishable goods can never be used as currency, other than in bartering. One criterion that is regarded as critical for any currency backing material is its fungibility. Alternative views suggest paper money backed by energy (measured for example in "joules of electricity" or "joules of oil"), transport (measured in kg·km/h), hours of labor or food for instance, may be used in the future.

See also

- Commodity money

- Disney Dollar

- Dogecoin

- Gold standard

- History of the United States dollar

- Kirtland Safety Society

- Local Exchange Trading Systems

- Monero

- Nxt

- Peercoin

- Prison commissary

- Scrip

- Store of value

- Ven (currency)

References

- ↑ "Florida man launches 'United States Private Dollar'", Daily Kos, August 25, 2007.

- ↑ "TUC Currencies", United Cities website, via Internet Archive

- ↑ "TUC Improving the US Economy by the Circulation of Their Private Currency Today", OpenPR.com August 2, 2007

- 1 2 "Kissimmee nonprofit 'concerned' over checks", Orlando Sentinel, August 25, 2007

- ↑ "Embattled company ups the ante", Orlando Sentinel, September 1, 2007

- ↑ Casey Sanchez, "Return of the Sovereigns," Spring 2009, Issue 133, Southern Poverty Law Center, at .

- ↑ Indictment, United States v. Cruz, case no. 6:08-cr-00177-UA-DAB, docket entry 1, Aug. 6, 2008, U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida (Orlando Div.).

- ↑ News Release, Aug. 22, 2008, "Orlando and Miami Men Indicted for Bank Fraud," U.S. Dep't of Justice, at .

- ↑ Status Report, United States v. Cruz, case no. 6:08-cr-00177-UA-DAB, docket entry 88, Oct. 28, 2010, U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida (Orlando Div.).

- ↑ Judgment, United States v. Marrero, case no. 6:08-cr-00177-UA-DAB, docket entry 75, Sept. 1, 2009, U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida (Orlando Div.).

- ↑ Harry William Marrero, inmate # 17525-018, Federal Bureau of Prisons, U.S. Dep't of Justice, at .

- ↑ "Defendant Convicted of Minting His Own Currency" (Press release). United States District Court for the Western District of North Carolina: U.S. Attorney's Office. March 18, 2011. Archived from the original on December 17, 2012.

- ↑ Lovett, Tom (March 19, 2011). "Local Liberty Dollar 'Architect' Bernard von NotHaus convicted". Evansville Courier & Press.

- ↑ Reserve Bank Act 1959 (Cth)

- ↑ Weerasooria, Wickrema (1976). "The Australian Bank Cheque - Some Legal Aspects". Monash University Law Review. 2 (2): 189–190. ISSN 0311-3140.

- ↑ Leo Hickman (16 September 2009). "Will the Brixton pound buy a brighter future?". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ↑ Kelly, Tom (6 February 2012). "We don't want to be part of 'clone town Britain': City launches its own currency to keep money local". Daily Mail. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- 1 2 Harvey, Dave (19 September 2012). "Bristol Pound launched to keep trade in the city". BBC West News. Retrieved 21 September 2012.

- ↑ "Karlsruhe (bonus system)" (in German). Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ↑ International Bank Note Society. "Hong Kong's 1,000 (HSBC) dollar note".

- 1 2 Vaishampayan, Saumya (19 August 2013). "Bitcoins are private money in Germany". Marketwatch. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013.

- 1 2 Nestler, Franz (16 August 2013). "Deutschland erkennt Bitcoins als privates Geld an (Germany recognizes Bitcoin as private money)". Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.

- ↑ Watts, Jake Maxwell. "Thailand's Bitcoin ban is not quite what it seems". Quartz. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ↑ Andy Greenberg (20 April 2011). "Crypto Currency". Forbes.com. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ Espinoza, Javier (22 September 2014). "Is It Time to Invest in Bitcoin? Cryptocurrencies Are Highly Volatile, but Some Say They Are Worth It". Journal Reports. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ↑ Farivar, Cyrus (2013-08-07). "Federal judge: Bitcoin, "a currency," can be regulated under American law". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2013-08-15.

- ↑ "Securities and Exchange Commission v. Shavers et al, 4:13-cv-00416 (E.D.Tex.)". Docket Alarm, Inc. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

Further reading

- Hayek, Friedrich A. Denationalization of Money: An Analysis of the Theory and Practice of Concurrent Currencies 1977. ISBN 978-0-255-36087-6