Protectorate General to Pacify the West

| Protectorate General to Pacify the West | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 安西都護府 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 安西都护府 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Xinjiang |

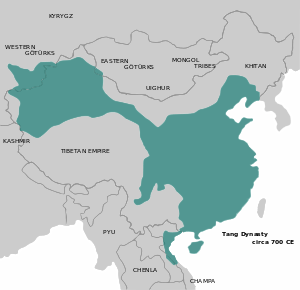

The Protectorate General to Pacify the West, Grand Protectorate General to Pacify the West, or Anxi Protectorate (640–790) was a Chinese outpost established by the Tang Dynasty in 640 to control the Tarim Basin.[1] The head office was first established at the Chinese prefecture of Xizhou, but was later shifted to Kucha and situated there for most of the period.[2] The Four Garrisons of Anxi, Kucha, Khotan, Kashgar, and Karashahr were later installed between 648 and 658 as garrisons under the western protectorate's command. In 659 Soghd and Ferghana along with cities like Tashkent, Samarkand, Balkh, Herat, and Kabul became part of the protectorate under Emperor Gaozong.[3] Afghanistan's Herat and Uzbekistan's Bukhara and Samarkand became part of the Tang protectorate.[4][5] The defeat of the Western Turks and the defeat of the Sassanids by the Arabs had facilitated the Chinese expansion under Emperor Gaozong into Herat, northeastern Iran and Afghanistan (Tukharistan), Bukhara, Samarkand, Tashkent, and Soghdiana which previously belonged to the western Turks.[6] Kashmir, Kabul, Tokharistan, Pamir, and Tashkent came under the Chinese protectorate.[7] After the Anshi Rebellion the office of Protector General was given to Guo Xin who defended the area and the four garrisons even after communication had been cut off from Chang'an by the Tibetan Empire. The last five years of the protectorate are regarded as an uncertain period in its history, but most sources agree that the last vestiges of the protectorate and its garrisons were defeated by Tibetan forces by the year 791, ending nearly 150 years of Tang influence in central Asia.

Legacy

Coins with both Chinese and Karoshthi inscriptions have been found in the southern Tarim Basin.[8]

It was the An Lushan Rebellion and not the defeat at Talas that ended the Tang Chinese presence in Central Asia and forced them to withdraw from Xinjiang- the significance of Talas was overblown, because the Arabs did not proceed any further after the battle.[9] Because the Arabs did not proceed to Xinjiang at all, the battle was of no importance strategically, it was An Lushan's rebellion which ended up forcing the Tang Chinese out of Central Asia.[10] Despite the conversion of some Karluk Turks after the Battle of Talas, the majority of Karluks did not convert to Islam until the mid 10th century under Sultan Satuq Bughra Khan when they established the Kara-Khanid Khanate.[11][12][13][14][15][16] This was long after the Tang dynasty was gone from Central Asia.

The military victories of the Tang in the western regions and Central Asia have been offered as explanations as to why western peoples referred to China by the name "House of Tang" (Tangjia) and another theory was suggested that China was called "Han" because of the Han dynasty military victories against peoples in the north, and the Turkic word for China, "Tamghaj" has been possibly derived from Tangjia instead of Tabgatch (Tuoba).[17]

In the Chu valley in Central Asia Tang dynasty era Chinese coins continued to be copied and minted after the Chinese left the area.[18]

An indelible impression was left on eastern Xinjiang's administration and culture in Turfan by the Chinese Tang rule which consisted of settlements, and military farms in addition to the spread of Chinese influence such as the sancai three colour glaze in Central Asia and Western Eurasia, in Xinjiang there was continued circulation of Chinese coins.[19]

The Buddhist Khitan Kara-Khitan Khanate conquered a large part of Central Asia from the Muslim Karluk Kara-Khanid Khanate in the 12th century. The Kara-Khitans also reintroduced the Chinese system of Imperial government, since China was still held in respect and esteem in the region among even the Muslim population,[20][21] and the Kara-Khitans used Chinese as their main official language.[22] The Kara-Khitan rulers were called "the Chinese" by the Muslims.[23]

Turkic Empires after the Tang gained prestige by connecting themselves with north Chinese states with the Qara-Khitay and Qara-Khanid khans using the title of "Chinese emperor", Khitay was used by the Qara-Khitay and Tabghach was used by the Qarakhanids.[24] The entry into the previously Indo-European Soghdian and Tokharian speaking Central Eurasia and Xinjiang of tribes of Turkic speaking origin and the started of Turkicisation originate in the 7th century with the disintegration of the Turkic Khaganate, resulting in Eurasia being populated by many peoples who consider themselves Turks..

Two different branches, the junior Bughra (bull camel) and the Arslan (lion) formed the Qarakhanid royal family. The title "Khan of China" (Tamghaj Khan) (تمغاج خان) was used by the Qarakhanid rulers.[25] The Qarakhanids were the ones who are responsible for the modern Uyghur population being Muslim and the Qarakhanids were converted when Satuq Bughra Khan converted to Islam after contacts with the Muslim Samanids.

Bughra Khan was overthrown by his nephew Satuq when Satuq converted to Islam, the Arslan Khans were also toppled and Balasaghun taken by Satuq, with the conversion of the Qarakhanid Turk population to Islam following Satuq's accession to power and the spread of Islam among the Qarakhanid Turks led to the conquest of Transoxiana and the Samanids by the Qarakhanids and the Qarakhanids were the people who bequeathed the Islamic religion to the modern Uyghurs while the modern Uyghurs adopted the modern name of their ethnic group from the Uyghur Qocho Kingdom and Uyghur Empire.[26]

The Turkic Qarakhanid and Uyghur Qocho Kingdoms were both states founded by invaders while the native populations of the region were Iranic and Tocharian peoples along with some Chinese in Qocho and Indians, who married and mixed with the Turkic invaders, and prominent Qarakhanid people such as Mahmud Kashghari hold a high position among modern Uyghurs.[27]

Kashghari viewed the least Persian mixed Turkic dialects as the "purest" and "the most elegant".[28]

Persian, Arab and other western Asian writers called China by the name "Tamghaj".[29]

The Qarakhanid ruler of Kashgar was called Tamghaj Khan, while the Khitan ruler was called the Khan of Chīn, some Khitans migrated into western areas like the Qarakhanid state even before the establishment of the Kara-Khitan state.[30]

During the Liao dynasty Han Chinese lived in Kedun, situated in present-day Mongolia.[31]

In 1124 the migration of the Khitan under Yelü Dashi included a big part of the Kedun population, which consisted of Han Chinese, Bohai, Jurchen, Mongol tribes, Khitan, in addition to the Xiao consort clan and the Yelü royal family on the march to establish the Qara-Khitan.[32]

The Kara-Khitai had among its court languages, the Chinese language.[33]

The Khitan Qara-Khitai empire in Central Asia kept Chinese characteristics in their state since the Chinese characteristics appealed to the Muslim Central Asians and helped validate Qara Khita rule over them, despite the fact that Han Chinese were to be found among the population of the Qara Khitan because it was comparatively small so it is clear that the Chinese characteristics were not kept to appease them, the Mongols later moved more Han Chinese into Besh Baliq, Almaliq and Samarqand in Central Asia to work as aristans and farmers.[34]

The Qara Khitai used the "image of China" to legitimize their ruler to the Central Asian Muslims since China had a good reputation at the time among Central Asian Muslims before the Mongol invasions, it was viewed as extremely civilized, known for its unique script, its expert artisans were well known, justice and religious tolerance were among the virtues attributed to Chinese despite their idol worship and the Turk, Arab, Byzantium, Indian rulers, and the Chinese emperor were known as the world's "five great kings", the memory of Tang China was engraved into the Muslim perception so their continued to view China through the lens of the Tang dynasty and anachronisms appeared in Muslim writings due to this even after the end of the Tang, China was known as chīn (چين) in Persian and as ṣīn (صين) in Arabic while the Tang dynasty capital Changan was known as Ḥumdān (خُمدان).[35]

Muslim Muslim writers like Marwazī and Mahmud Kashghārī had more up to date information about China in their writings, Kashgari viewed Kashgar as part of China. Ṣīn [i.e., China] is originally three fold; Upper, in the east which is called Tawjāch; middle which is Khitāy, lower which is Barkhān in the vicinity of Kashgar. But know Tawjāch is known as Maṣīn and Khitai as Ṣīn" China was called after the Toba rulers of the Northern Wei by the Turks, pronounced by them as Tamghāj, Tabghāj, Tafghāj or Tawjāch. India introduced the name Maha Chin (greater China) which caused the two different names for China in Persian as chīn and māchīn (چين ماچين) and Arabic ṣīn and māṣīn (صين ماصين), Southern China at Canton was known as Chin while Northern China's Changan was known as Machin, but the definition switched and the south was referred to as Machin and the north as Chin after the Tang dynasty, Tang China had controlled Kashgar since of the Tang's Anxi protectorate's "Four Garrisons" seats, Kashgar was among them, and this was what led writers like Kashghārī to place Kashgar within the definition of China, Ṣīn, whose emperor was titled as Tafghāj or Tamghāj, Yugur (yellow Uighurs or Western Yugur) and Khitai or Qitai were all classified as "China" by Marwazī while he wrote that Ṣīnwas bordered by placed SNQU and Maṣīn.[36] Machin, Mahachin, Chin, and Sin were all names of China.[37]

Muslim writers like Marwazī wrote that Transoxania was a former part of China, retaining the legacy of Tang Chinese rule over Transoxania in Muslim writings, In ancient times all the districts of Transoxania had belonged to the kingdom of China [Ṣīn], with the district of Samarqand as its centre. When Islam appeared and God delivered the said district to the Muslims, the Chinese migrated to their [original] centers, but there remained in Samarqand, as a vestige of them, the art of making paper of high quality. And when they migrated to Eastern parts their lands became disjoined and their provinces divided, and there was a king in China and a king in Qitai and a king in Yugur., Muslim writers viewed the Khitai, the Gansu Uighur Kingdom and Kashgar as all part of "China" culturally and geographically with the Muslim Central Asians retaining the legacy of Chinese rule in Central Asia by using titles such as "Khan of China" (تمغاج خان) (Tamghaj Khan or Tawgach) in Turkic and "the King of the East and China" (ملك المشرق (أو الشرق) والصين) (malik al-mashriq (or al-sharq) wa'l-ṣīn) in Arabic which were titles of the Muslim Qarakhanid rulers and their Qarluq ancestors.[38][39] After Yusuf Qadir Khan's conquest of new land in Altishahr towards the east, he adopted the title "King of the East and China".[40]

The title Malik al-Mashriq wa'l-Ṣīn was bestowed by the 'Abbāsid Caliph upon the Tamghaj Khan, the Samarqand Khaqan Yūsuf b. Ḥasan and after that coins and literature had the title Tamghaj Khan appear on them and were continued to be used by the Qarakhanids and the Transoxania-based Western Qarakhanids and some Eastern Qarakhanid monarchs, so therefore the Kara-Khitan (Western Liao)'s usage of Chinese things such as Chinese coins, the Chinese writing system, tablets, seals, Chinese art products like porcelein, mirrors, jade and other Chinese customs were designed to appearl to the local Central Asian Muslim population since the Muslims in the area regarded Central Asia as former Chinese territories and viewed links with China as prestigious and Western Liao's rule over Muslim Central Asia caused the view that Central Asia was a Chinese territory to reinforce upon the Muslims; "Turkestan" and Chīn (China) were identified with each other by Fakhr al-Dīn Mubārak Shāh with China being identified as the country where the cities of Balāsāghūn and Kashghar were located.[41]

The Liao Chinese traditions and the Qara Khitai's clinging helped the Qara Khitai avoid Islamization and conversion to Islam, the Qara Khitai used Chinese and Inner Asian features in their administrative system.[42]

Muslim writers wrote that "Tamghājī silver coins" (sawmhā-yi ṭamghājī) were present in Balkh while tafghājī was used by the writer Ḥabībī, the Qarakhānid leader Böri Tigin (Ibrāhīm Tamghāj Khān) was possibly the one who minted the coins.[43]

| Duhu Tang dynasty |

|---|

The relationship to China was used by the Qara-Khanids to enhace their standing since Central Asian Muslims associated prestige and grandeur with China so the Arabic title "the king of the East and China" (malek al-mašreq wa’l-Ṣin) and the Turkic title "Khan of China" Ṭamḡāj Khan was extensively employed by Khans of the Qara-khanids.[44]

The following account of the country of Yaghma and its towns is given in the tenth century text Hudud al-'alam:

East of the Toquz-Oghuz country; south of it, the river Khuland-ghun which flows into the Kucha river, west of it are the Qarluq borders. In this country there is little agriculture, (yet) it produces many furs and in it much game is found.Their wealth is in horses and sheep. The people are hardy, strong, and warlike, and have plenty of arms. Their king is from the family of the Toquz-Oghuz kings. These Yaghma have numerous tribes; some say that among them 1,700 known tribes are counted. Both the low and the nobles among them venerate their king ...and in their region there are a few villages.

1. Kashghar belongs to Chinistan but is situated on the frontier between the Yaghma, Tibet, the Qïrghïz, and China. The chiefs of Kashghar in the days of old were from the Qarluq, or from the Yaghma...

— Hudud al-'alam[45]

Although in modern Urdu Chin means China, Chin referred to Central Asia in Muhammad Iqbal's time, which is why Iqbal wrote that "Chin is ours" (referring to the Muslims) in his song Tarana-e-Milli.[46]

Aladdin, an Arabic Islamic story which is set in China, may have been referring to Central Asia.[47]

In the Persian epic Shahnameh the Chin and Turkestan are regarded as the same, the Khan of Turkestan is called the Khan of Chin.[48][49][50]

The Tang Chinese reign over Qocho and Turfan and the Buddhist religion left a lasting legacy upon the Buddhist Uyghur Kingdom of Qocho with the Tang presented names remaining on the more than 50 Buddhist temples with Emperor Tang Taizong's edicts stored in the "Imperial Writings Tower " and Chinese dictionaries like Jingyun, Yuian, Tang yun, and da zang jing (Buddhist scriptures) stored inside the Buddhist temples and Persian monks also maintained a Manichaean temple in the Kingdom., the Persian Hudud al-'Alam uses the name "Chinese town" to call Qocho, the capital of the Uyghur kingdom.[51]

The Turfan Buddhist Uighurs of the Kingdom of Qocho continued to produce the Chinese Qieyun rime dictionary and developed their own pronunciations of Chinese characters, left over from the Tang influence over the area.[52]

The modern Uyghur linguist Abdurishid Yakup pointed out that the Turfan Uyghur Buddhists studied the Chinese language and used Chines books like Qianziwen (the thousand character classic) and Qieyun *(a rime dictionary) and it was written that "In Qocho city were more than fifty monasteries, all titles of which are granted by the emperors of the Tang dynasty, which keep many Buddhist exts as Tripitaka, Tangyun, Yupuan, Jingyin etc." [53]

In Central Asia the Uighurs viewed the Chinese script as "very prestigious" so when they developed the Old Uyghur alphabet, based on the Syriac script, they deliberately switched it to vertical like Chinese writing from its original horizontal position in Syriac.[54]

List of protector generals

List of Chinese grand and assistant protectors of Pacify the West:[56]

Protectorate:

- Qiao Shiwang (喬師望) 640–642

- Guo Xiaoke (郭孝恪) 642–649

- Chai Zhewei (柴哲威) 649–651

- Qu Zhizhan (麴智湛) 651–658

Grand Protectorate:

- Yang Zhou (楊胄) 658–662

- Su Haizheng (蘇海政) 662

- Gao Xian (高賢) 663

- Pilou Shiche (匹婁武徹) 664

- Pei Xingjian (裴行儉) 665–667

Protectorate:

- Tao Dayou (陶大有) 667–669

- Dong Baoliang (董寶亮) 669–671

- Yuan Gongyu (袁公瑜) 671–677

- Du Huanbao (杜懷寶) 677–679,

- Wang Fangyi (王方翼) 679–681

- Du Huanbao (杜懷寶) 681–682

- Li Zulong (李祖隆) 683–685

Grand Protectorate:

- Wang Shiguo (王世果) 686–687

- Yan Wengu (閻溫古) 687–689

Protectorate:

- Jiu Bin (咎斌) 689–690

- Tang Xiujing (唐休璟) 690–693

Grand Protectorate:

- Xu Qinming (許欽明) 693–695

- Gongsun Yajing (公孫雅靖) 696–698

- Tian Yangming (田揚名) 698–704

- Guo Yuanzhen (郭元振) 705–708,

- Zhou Yiti (周以悌) 708–709

- Guo Yuanzhen (郭元振) 709–710

- Zhang Xuanbiao (張玄表) 710–711

- Lu Xuanjing (呂玄璟) 712–716

- Guo Qianguan (郭虔瓘) 715–717,

- Li Cong (李琮) 716

- Tang Jiahui (湯嘉惠) 717–719,

- Guo Qianguan (郭虔瓘) 720–721

- Zhang Xiaosong (張孝嵩) 721–724

- Du Xian (杜暹) 724–726

- Zhao Yizhen (趙頤貞) 726–728

- Xie Zhixin (謝知信) 728

- Li Fen (李玢) 727–735

- Zhao Hanzhang (趙含章) 728–729

- Lu Xiulin (吕休琳) 729–730

- Tang Jiahui (湯嘉惠) 730

- Lai Yao (萊曜) 730–731

- Xu Qinshi (徐欽識) 731–733

- Wang Husi (王斛斯) 733–738

- Ge Jiayun (蓋嘉運) 738–739

- Tian Renwan (田仁琬) 740–741

- Fumeng Lingcha (夫蒙靈詧) 741–747

- Gao Xianzhi (高仙芝) 747–751

- Wang Zhengjian (王正見) 751–752

Protectorate:

- Feng Changqing (封常清) 752–755

- Liang Zai (梁宰) 755–756

- Li Siye (李嗣業) 756–759

- Lifei Yuanli (荔非元禮) 759–761

- Bai Xiaode (白孝德) 761–762

- Sun Zhizhi (孫志直) 762–765

- Guo Xin (郭昕) 762–787 (uncertain as to what actually happened after the An Lushan Rebellion)

See also

- Protectorate General to Pacify the North

- Protectorate General to Pacify the East

- Chinese military history

- Horses in East Asian warfare

- Tang dynasty in Inner Asia

- Four Garrisons of Anxi

- Protectorate of the Western Regions

References

Citations

- ↑ Michael Robert Drompp (2005). Tang China and the collapse of the Uighur Empire: a documentary history. Volume 13 of Brill's Inner Asian library (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 103. ISBN 90-04-14129-4. Retrieved February 2012 8.

19 The Protectorate-General (duhufu) of Anxi ("Pacified West") was established in 640 by the Tang emperor Taizong as the Chinese administrative unit for the control of various city-states of the Tarim Basin. Its administrative center was based

Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ↑ Michael Robert Drompp (2005). Tang China and the collapse of the Uighur Empire: a documentary history. Volume 13 of Brill's Inner Asian library (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 104. ISBN 90-04-14129-4. Retrieved February 2012 8.

In Qocho (Chinese Gaochang, later Xizhou) from 640 to 649, and then in Kucha from 649 until 670, when it was moved back to Qocho due to Tibetan conquests in the Tarim region. . . . In 791, Anxi fell to the Tibetans and was abandoned by the Chinese. . . The Uighurs, who were defeated along with the Chinese, soon recovered and reestablished control over both Qocho and Kucha, which became important centers of Western Uighur power after the collapse of the Uighur empire.

Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - ↑ Haywood, John; Jotischky, Andrew; McGlynn, Sean (1998). Historical Atlas of the Medieval World, AD 600-1492. Barnes & Noble. p. 3.20. ISBN 978-0-7607-1976-3.

- ↑ Harold Miles Tanner (13 March 2009). China: A History. Hackett Publishing. pp. 167–. ISBN 0-87220-915-6.

- ↑ Harold Miles Tanner (12 March 2010). China: A History: Volume 1: From Neolithic cultures through the Great Qing Empire 10,000 BCE–1799 CE. Hackett Publishing Company. pp. 167–. ISBN 978-1-60384-202-0.

- ↑ H. J. Van Derven (1 January 2000). Warfare in Chinese History. BRILL. pp. 122–. ISBN 90-04-11774-1.

- ↑ René Grousset (January 1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Rutgers University Press. pp. 119–. ISBN 978-0-8135-1304-1.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ S. Frederick Starr (15 March 2004). Xinjiang: China's Muslim Borderland. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-0-7656-3192-3.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 36–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ André Wink (2002). Al-Hind: The Slavic Kings and the Islamic conquest, 11th-13th centuries. BRILL. pp. 68–. ISBN 0-391-04174-6.

- ↑ André Wink (1997). Al-Hind the Making of the Indo-Islamic World: The Slave Kings and the Islamic Conquest : 11Th-13th Centuries. BRILL. pp. 68–. ISBN 90-04-10236-1.

- ↑ Ira M. Lapidus (29 October 2012). Islamic Societies to the Nineteenth Century: A Global History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 230–. ISBN 978-0-521-51441-5.

- ↑ John L. Esposito (1999). The Oxford History of Islam. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 351–. ISBN 978-0-19-510799-9.

- ↑ Ayla Esen Algar (1992). The Dervish Lodge: Architecture, Art, and Sufism in Ottoman Turkey. University of California Press. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-0-520-07060-8.

- ↑ Svat Soucek (17 February 2000). A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84–. ISBN 978-0-521-65704-4.

- ↑ Yang, Shao-yun (2014). "Fan and Han: The Origins and Uses of a Conceptual Dichotomy in Mid-Imperial China, ca. 500-1200". In Fiaschetti, Francesca; Schneider, Julia. Political Strategies of Identity Building in Non-Han Empires in China. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 27–28.

- ↑ Belyaev, Vladimir; Nastich, Vladimir; Sidorovich, Sergey (2014). "Fan and Han: The Origins and Uses of a Conceptual Dichotomy in Mid-Imperial China, ca. 500-1200". The coinage of Qara Khitay: a new evidence (on the reign title of the Western Liao Emperor Yelü Yilie). Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences. p. 3.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 41–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ Michal Biran. "Michal Biran. "Khitan Migrations in Inner Asia," Central Eurasian Studies, 3 (2012), 85-108. - Michal Biran – Academia.edu".

- ↑ Biran 2012, p. 90.

- ↑ Tumen Jalafun Jecen Aku.

- ↑ Biran 2005, p. 93.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 52–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ Sir Henry Yule (1915). Cathay and the Way Thither, Being a Collection of Medieval Notices of China. Asian Educational Services. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-81-206-1966-1.

- ↑ Michal Biran (15 September 2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-0-521-84226-6.

- ↑ Michal Biran (15 September 2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-0-521-84226-6.

- ↑ Michal Biran (15 September 2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-0-521-84226-6.

- ↑ Frederick W. Mote (2003). Imperial China 900-1800. Harvard University Press. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.

- ↑ Michal Biran (15 September 2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 96–. ISBN 978-0-521-84226-6.

- ↑ Michal Biran (15 September 2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 97–. ISBN 978-0-521-84226-6.

- ↑ Michal Biran (15 September 2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 98–. ISBN 978-0-521-84226-6.

- ↑ Cordier, Henri. "China." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 14 Sept. 2015 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/03663b.htm>.

- ↑ Michal Biran (15 September 2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-0-521-84226-6.

- ↑ Schluessel, Eric T. (2014). "The World as Seen from Yarkand: Ghulām Muḥammad Khān's 1920s Chronicle Mā Tīṭayniŋ wā qiʿasi" (PDF). TIAS Central Eurasian Research Series (9). NIHU Program Islamic Area Studies: 13. ISBN 978-4-904039-83-0. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ↑ Thum, Rian (6 August 2012). "Modular History: Identity Maintenance before Uyghur Nationalism". The Journal of Asian Studies. The Association for Asian Studies, Inc. 2012. 71 (03): 633. doi:10.1017/S0021911812000629. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ Michal Biran (15 September 2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-0-521-84226-6.

- ↑ Michal Biran (15 September 2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. Cambridge University Press. pp. 102–. ISBN 978-0-521-84226-6.

- ↑ "ILAK-KHANIDS". Encyclopædia Iranica. Bibliotheca Persica Press. XII (Fasc. 6): 621–628. Originally Published: December 15, 2004 Last Updated: March 27, 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2015. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Arezou Azad (November 2013). Sacred Landscape in Medieval Afghanistan: Revisiting the Faḍāʾil-i Balkh. OUP Oxford. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-0-19-968705-3.

- ↑ Scott Cameron Levi, Ron Sela (2010). "Chapter 4, Discourse on the Country of the Yaghma and its Towns". Islamic Central Asia: An Anthology of Historical Sources. Indiana University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-253-35385-6.

- ↑ Although "Chin" refers to China in modern Urdu, in Iqbal's day it referred to Central Asia, coextensive with historical Turkestan. See also, Iqbal: Tarana-e-Milli, 1910. Columbia University, Department of South Asian Studies.

- ↑ Moon, Krystyn (2005). Yellowface. Rutgers University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-8135-3507-7.

- ↑ Bapsy Pavry (19 February 2015). The Heroines of Ancient Persia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-1-107-48744-4.

- ↑ the heroines of ancient persia. CUP Archive. pp. 86–. ISBN 978-1-00-128789-8.

- ↑ Bapsy Pavry Paulet Marchioness of Winchester (1930). The Heroines of Ancient Persia: Stories Retold from the Shāhnāma of Firdausi. With Fourteen Illustrations. The University Press. p. 86.

- ↑ James A. Millward (2007). Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang. Columbia University Press. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3.

- ↑ TAKATA, Tokio. "The Chinese Language in Turfan with a special focus on the Qieyun fragments" (PDF). Institute for Research in Humanities, Kyoto University: 7–9. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ↑ Abdurishid Yakup (2005). The Turfan Dialect of Uyghur. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 180–. ISBN 978-3-447-05233-7.

- ↑ Liliya M. Gorelova (1 January 2002). Manchu Grammar. Brill. p. 49. ISBN 978-90-04-12307-6.

- ↑ Lee Lawrence. (3 September 2011). "A Mysterious Stranger in China". The Wall Street Journal. Accessed on 31 August 2016.

- ↑ Xue, p. 589-593

Sources

- Xue, Zongzheng (薛宗正). (1992). Turkic peoples (突厥史). Beijing: 中国社会科学出版社. ISBN 978-7-5004-0432-3; OCLC 28622013

Coordinates: 41°39′N 82°54′E / 41.650°N 82.900°E