Pyramid of Senusret III

The pyramid of Senusret III in the 1890s | |

| Senusret III, 12th Dynasty | |

| Coordinates | 29°49′8″N 31°13′32″E / 29.81889°N 31.22556°ECoordinates: 29°49′8″N 31°13′32″E / 29.81889°N 31.22556°E |

| Constructed | 19th century BCE |

| Type | True pyramid (now ruined) |

| Material |

Mudbrick (core) Tura limestone (casing) |

| Height | 78 m (256 ft) |

| Base | 105 m (344 ft) |

| Volume | 288,488 m3 (10,187,900 cu ft) |

| Slope | 56° 18' 35" |

The Pyramid of Senusret III (Lepsius XLVII) is an ancient Egyptian pyramid located at Dahshur and built for pharaoh Senusret III of the 12th Dynasty (19th century BCE).

The pyramid is the northernmost among those of Dahshur, and stands around 1.5 km northeast of Sneferu's Red Pyramid. It was erected on leveled ground and composed of a mudbricks core covered with a casing of white Tura limestone blocks resting on foundations. It was first excavated in 1894 by the French Egyptologist Jacques de Morgan, who managed to reach the burial chamber after discovering a tunnel dug by ancient tomb robbers.[1] A more recent campaign was led by Dieter Arnold during the 1990s.

Pyramid complex

The original project included the main pyramid along with a northern chapel and a small eastern mortuary temple, all surrounded by an enclosure wall. Outside this enclosure were seven tombs belonging to Senusret's queens and princesses, and the whole complex was again surrounded by an outer wall; this wall was enlarged during the works on order to accommodate a large temple on the southern side and a causeway.[1] The remains of six sacred barques were excavated outside the outer enclosure on the southern side.[2]

The now-demolished eastern temple was very small in size, perhaps a sign of the decline of the traditional funerary cult, as Arnold suggested. On the remaining reliefs were depicted conventional scenes of offerings to the enthroned Senusret III. The southern temple was likely demolished during the New Kingdom and according to its foundations it consisted in a colonnaded courtyard and an inner shrine. The valley temple has not been discovered.[3]

Many shaft tombs belonged to the royal women were discovered on the northern and southern sides of the main pyramid; it was believed that these shafts were topped by mastabas until Arnold in 1997 demonstrated that these consisted in the intricated rock-cut hypogea of seven small pyramids. Explorations of the northern tombs led to the discovery of the treasures of princesses Sithathor and Mereret (among these objects, the famous pectorals with the names of Senusret II, Senusret III and Amenemhat III now exhibited at the Cairo Museum), as well as the sarcophagi of princesses Menet and Senetsenebtisi and of queen Neferthenut.[2][4] Among the southern tombs, the easternmost was discovered in 1994 and its hypogeum led to a burial chamber located under the main pyramid. Here, a granite sarcophagus was found, along with some objects bearing the name of Khenemetneferhedjet I Weret, Senusret III's royal mother.[2]

Hypogeum

De Morgan struggled for months to find the original entrance; after digging several tunnels directed towards the center of the monument, he finally found the thieves' tunnel. One of the passages was covered by graffiti which were rather alien to the Egyptian canons, the most famous among these represents a human head with a striking hairstyle. De Morgan argued that the tunnels and the graffiti were made by Semitic grave robbers during the Hyksos occupation. From the thieves' tunnels, de Morgan was able to trace the original entrance.[5]

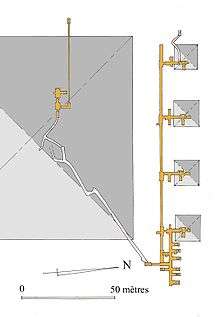

From the entrance, located on the western side of the pyramid, a long descending hallway led to an antechamber which connects a storeroom on the west wall to the king's chamber on the east wall, the latter made from granite and provided with a granite sarcophagus on the western side, and a niche for the canopic chest on the southern one. The granite walls of the burial chamber were whiten with gypsum. Above the chamber Arnold found three relieving vaults made from granite (the bottom one), limestone (the middle one) and mudbricks (the top one) which were meant to discharge the weight on the underlying chamber's walls in order to prevent a roof collapse. The king's chamber contained pottery and a dagger, while the granite sarcophagus was empty. It is possible that Senusret III was never buried there and that he might have preferred his Abydene tomb as his final resting place, as suggested by the lack of a blocking system within this hypogeum.[1]

Sources

- Cimmino, Franco (1996). Storia delle Piramidi. Milano: Rusconi. ISBN 88-18-70143-6.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Blackwell Books. ISBN 9780631174721.

- Lehner, Mark (1997). The Complete Pyramids. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05084-8.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pyramid of Senusret III. |

- Arnold, Dieter (2002). The Pyramid Complex of Senwosret III at Dahshur, Architectural Studies. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0-87099-956-7.

- de Morgan, Jacques (1895). Fouilles à Dahchour: Mars–Juin 1894. Vienne: Adolphe Holzhausen.