Ratha

Ratha (Sanskrit: रथ, rátha, Avestan raθa) is the Indo-Iranian term for a spoked-wheel chariot or a cart of antiquity.

The Rigvedic word rá-tha does not denote a war-chariot like those of Andronovo, Egypt, Greece, and Rome. The word is from √ṛ ‘go’ giving primary rá-tha ‘a goer, car, vehicle’. Similar formations exist with the suffix -tha: ártha ‘goal’, ukthá ‘saying’, ǵāthā ‘song’ etc. The rigvedic ratha is described as pṛthu ‘broad’ 1.123.1; bṛhat ‘tall, big’ 6.61.13; variṣṭha ‘widest’ 6.47.9. It has space not for 1 only or 2 (i.e. the driver and the warrior with his spear and bow) but for 3: it is said to be trivandhurá (1.41.2; 7.71.4) and then to carry 8 aṣṭāvandhurá (10.53.7)[1]

Textual evidence

Chariots figure prominently in the Rigveda, evidencing their presence in India in the 2nd millennium BCE. Notably, the Rigveda differentiates between the Ratha (chariot) and the Anas (often translated as "cart").[2] Rigvedic chariots are described as made of the wood of Salmali (RV 10.85.20), Khadira and Simsapa (RV 3.53.19) trees. While the number of wheels varies, chariot measurements for each configuration are found in the Shulba Sutras.

Chariots also feature prominently in later texts, including the other Vedas, the Puranas and the great Hindu epics (Ramayana and Mahabharata). Indeed, most of the deities in the Hindu pantheon are portrayed as riding them. Among Rigvedic deities, notably Ushas (the dawn) rides in a chariot, as well as Agni in his function as a messenger between gods and men. In RV 6.61.13, the Sarasvati river is described as being wide and speedy, like a (Rigvedic) chariot.

History

Indus Valley Civilization

At Harappa in modern-day Pakistan we find evidence for the use of terracotta model carts as early as 3500 BC during the Ravi Phase at Harappa.

During the Harappan Period (Harappa Phase, 2600...1900 BC) there was a dramatic increase in terracotta cart and wheel types at Harappa and other sites throughout the Indus region. The diversity in carts and wheels, including depictions of what may be spoked wheels, during this period of urban expansion and trade may reflect different functional needs, as well as stylistic and cultural preferences. The unique fonns and the early appearance of carts in the Indus valley region suggest that they are the result of indigenous technological development and not diffusion from West Asia or Central Asia as proposed by earlier scholars.[3]

Proto-Indo-Iranians

Development of the spoke-wheeled chariot is associated with the Proto-Indo-Iranians. The earliest fully developed war chariots known are from the chariot burials of the Andronovo (Timber-Grave) sites of the Sintashta-Petrovka culture in modern Russia and Kazakhstan dating from around 2000 BCE.

The chariot must not necessarily be regarded as a marker for Indo-European or Indo-Iranian presence.[4] According to Raulwing, it is an undeniable fact that only comparative Indo-European linguistics is able to furnish the methodological basics of the hypothesis of a "PIE chariot", in other words: "Ausserhalb der Sprachwissenschaft winkt keine Rettung![5]"[6][7]

The earliest evidence for chariots in southern Central Asia (on the Oxus) dates to the Achaemenid period (apart from chariots harnessed by oxen, as seen on petroglyphs).[8] No Andronovian chariot burial has been found south of the Oxus.[9]

Remains

There are a few depictions of chariots among the petroglyphs in the sandstone of the Vindhya range. Two depictions of chariots are found in Morhana Pahar, Mirzapur district. One shows a team of two horses, with the head of a single driver visible. The other one is drawn by four horses, has six-spoked wheels, and shows a driver standing up in a large chariot-box. This chariot is being attacked, with a figure wielding a shield and a mace standing at its path, and another figure armed with bow and arrow threatening its right flank. It has been suggested (Sparreboom 1985:87) that the drawings record a story, most probably dating to the early centuries BC, from some center in the area of the Ganges–Yamuna plain into the territory of still neolithic hunting tribes. The drawings would then be a representation of foreign technology, comparable to the Arnhem Land Aboriginal rock paintings depicting Westerners. The very realistic chariots carved into the Sanchi stupas are dated to roughly the 1st century.

The earliest chariot remains that have been found in India (at Atranjikhera) has been dated to between 350 and 50 BCE.[10] There is evidence of wheeled vehicles (especially miniature models) in the Indus Valley Civilization, but not of chariots.[11]

Indus valley sites have offered several instances of evidence of spoked wheels. Archaeologist B. B. Lal[12] argues that finds of terracotta wheels painted lines (or low relief lines) and similar seals indicate the existence and use of spoked wheel chariots in Harappan Civilization, as showed in the Bhirrana excavations in 2005-06.[13] Bhagwan Singh[14] had made a similar assertion and S.R.Rao had presented evidence of chariots in bronze models from Daimabad (Late Harappan). The archaeologists at Daimabad are not unanimous about the date of the bronzes discovered there. On the basis of the circumstantial evidence, M. N. Deshpande, S. R. Rao and S. A. Sali are of view that these objects belong to the Late Harappan period. Looking at the analysis of the elemental composition of these artifacts, D. P. Agarwal concluded that these objects may belong to the historical period. His conclusion is based on the fact these objects contain more than 1% Arsenic, while no arsenical alloying has been found in any other Chalcolithic artifacts.[15]

In Hindu temple festivals

Ratha or Rath means a chariot or car made from wood with wheels. The Ratha may be driven manually by rope, pulled by horses or elephants. Rathas are used mostly by the Hindu temples of South India for Rathoutsava (Car festival). During the festival, the temple deities are driven through the streets, accompanied by the chanting of mantra, hymns, shloka or bhajan.

Ratha Yatra is a huge Hindu festival associated with Lord Jagannath held at Puri in the state of Orissa, India during the months of June or July.

- Ratha or chariots

The Towering Rajagopuram with one of the Temple Rathas

The Towering Rajagopuram with one of the Temple Rathas The Great Thear (ஆழித் தேர்) of Sri Thyagarajaswami, Tiruvarur

The Great Thear (ஆழித் தேர்) of Sri Thyagarajaswami, Tiruvarur The Rath Yatra in Puri in modern times showing the three chariots of the deities with the Temple in the background

The Rath Yatra in Puri in modern times showing the three chariots of the deities with the Temple in the background Picture of Tirunelveli Nellaiappar Temple Golden Ratha

Picture of Tirunelveli Nellaiappar Temple Golden Ratha

Temple chariot (decorated), Udupi, Karnataka, India

Temple chariot (decorated), Udupi, Karnataka, India- ISKCON Rath Yatra at Thiruvananthapuram, India.

Tiruvarur The largest Temple Ratha car in Tamil Nadu

Tiruvarur The largest Temple Ratha car in Tamil Nadu Srivilliputtur Andal Ther - 2nd largest Temple Rath in Tamil Nadu

Srivilliputtur Andal Ther - 2nd largest Temple Rath in Tamil Nadu Tirunelveli Nellaiappar Temple Car - 3rd largest Temple Ratha in Tamil Nadu - Picture taken on July 5, 2009 on 505th Car festival of Tirunelveli

Tirunelveli Nellaiappar Temple Car - 3rd largest Temple Ratha in Tamil Nadu - Picture taken on July 5, 2009 on 505th Car festival of Tirunelveli

Rath Yatra festival in New York City organized by ISKCON

Rath Yatra festival in New York City organized by ISKCON Construction of ratha

Construction of ratha Banashankari Amma Temple's wooden Ratha, Badami, Karnataka (1855 photo)

Banashankari Amma Temple's wooden Ratha, Badami, Karnataka (1855 photo)- Decorated Ratha, Mundkur, Udupi District, Karnataka.

Rathas buildings

In some Hindu temples, there are shrines or buildings named rathas because they have the shape of a huge chariot. Or because they contains a divinity like does a temple chariot.

The most known are the Pancha Rathas (=5 rathas) in Mahabalipuram, although not with the shape of a chariot.

Another example is the Jaga mohan of the Konark Sun Temple in Konarâk, built on a platform with twelve sculptures of wheels, as a symbol of the chariot of the Sun.

- Buildings

'Five Rathas' at Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu.

'Five Rathas' at Mamallapuram, Tamil Nadu.

- Temple chariot of the Airavatesvara Temple in Darasuram, Tamil Nadu

- Konark Sun Temple Ratha wheel

Rathas in architecture

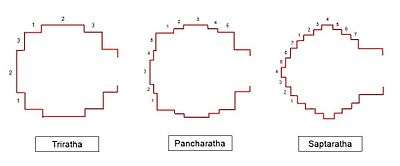

In Hindu temple architecture, a ratha is a facet or vertical offset projections on the tower (generally a Shikhara).

Rathas in popular culture

Artist's pseoudonym of Tori J. O'Shea, photographer and graphic novelist.[16]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Kazanas, Nicholas. "The Collapse of the AIT and the prevalence of Indigenism: archaeological, genetic, linguistic and literary evidences." (PDF). http://www.omilosmeleton.gr/. Retrieved 23 January 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ A discussion of the difference between ratha and anas is found e.g. in Kazanas, Nicholas. 2001. The AIT and Scholarship

- ↑ Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark. "Wheeled Vehicles of the Indus Valley Civilization of Pakistan and India." (PDF). http://a.harappa.com. Retrieved 23 January 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Cf. Raulwing 2000

- ↑ I. e., "Outside of linguistics there's no hope."

- ↑ Raulwing 2000:83

- ↑ Cf. Henri Paul Francfort in Fussman, G.; Kellens, J.; Francfort, H.-P.; Tremblay, X. (2005), p. 272-276

- ↑ They were not used for warfare. H. P. Francfort, Fouilles de Shortugai, Recherches sur L'Asie Centrale Protohistorique Paris: Diffusion de Boccard, 1989, p. 452. Cf. Henri Paul Francfort in Fussman, G.; Kellens, J.; Francfort, H.-P.; Tremblay, X. (2005), p.272

- ↑ H. P. Francfort in Fussman, G.; Kellens, J.; Francfort, H.-P.; Tremblay, X. (2005), p. 220 - 272; H.-P. Francfort, Fouilles de Shortugai

- ↑ (Bryant 2001)

- ↑ Bryant 2001

- ↑ The Sarasvati Flows on, 2002, pp.74-75, Figs 3.28 to 331

- ↑ L.S.Rao, Harappan Spoked Wheels Rattled Down the Streets of Bhirrana, Dist. Fatehabad, Haryana

- ↑ Harappan Civilization and the Vedic Literature, in Hindi, 1987

- ↑ Dhavalikar, M. K. (1982). Daimabad Bronzes (PDF). in Gregory L. Possehl. ed. Harappan Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Warminster: Aris and Phillips. pp. 361–66. ISBN 0-85668-211-X. C1 control character in

|pages=at position 5 (help) - ↑ http://blytzkrieg.deviantart.com

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ratha. |

- Bryant, Edwin (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513777-9.

- Fussman, G.; Kellens, J.; Francfort, H.-P.; Tremblay, X. (2005). Aryas, Aryens et Iraniens en Asie Centrale. Institut Civilisation Indienne ISBN 2-86803-072-6

- Kazanas, Nicholas (2001). The AIT and Scholarship. Omilos Meleton, Athens.

- Peter Raulwing (2000). Horses, Chariots and Indo-Europeans, Foundations and Methods of Chariotry Research from the Viewpoint of Comparative Indo-European Linguistics. Archaeolingua, Series Minor 13, Budapest.