Reichweiler

| Reichweiler | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

Reichweiler | ||

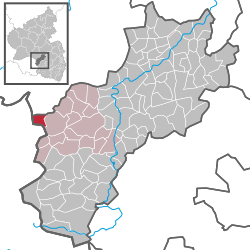

Location of Reichweiler within Kusel district  | ||

| Coordinates: 49°32′31.41″N 7°17′23.88″E / 49.5420583°N 7.2899667°ECoordinates: 49°32′31.41″N 7°17′23.88″E / 49.5420583°N 7.2899667°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | Rhineland-Palatinate | |

| District | Kusel | |

| Municipal assoc. | Kusel | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Bernd Hoffmann | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 3.87 km2 (1.49 sq mi) | |

| Population (2015-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 539 | |

| • Density | 140/km2 (360/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 66871 | |

| Dialling codes | 06384 | |

| Vehicle registration | KUS | |

Reichweiler is an Ortsgemeinde – a municipality belonging to a Verbandsgemeinde, a kind of collective municipality – in the Kusel district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the Verbandsgemeinde of Kusel, whose seat is in the like-named town.

Geography

Location

The municipality lies in the Westrich – an historic region that encompasses areas in both Germany and France – at the boundary with the Saarland. Reichweiler, once in the southeast of the Birkenfeld district but today in the westernmost Kusel district, stretches out at the southern foot of the Karrenberg, itself part of the Preußische Berge (Prussian Mountains), a mighty mountain chain that looms up northwest of the Pfeffelbach valley, reaching an average elevation of almost 600 m above sea level. The district’s highest peak is the Herzerberg (585 m), which lies within Reichweiler’s limits. A very important Roman road running from Metz to Mainz seems to have only run along what are now the village’s outskirts, since it was not founded until Frankish times. Today, Reichweiler has a connection to the Autobahn A 62 (Kaiserslautern–Trier), although this is not economically important to the village. Landesstraße 349, which comes from the Saarland and leads to Thallichtenberg, and which links to Bundesstraße 420, is only of importance to through traffic, as is also Kreisstraße 61 – or beyond the district boundary Kreisstraße 57 – to Berschweiler bei Baumholder. From the heights one has an outstanding view. Far to the north, the heights of the Hunsrück can be seen along their full length. To the east lies Germany’s biggest castle ruin, Castle Lichtenberg, while to the southeast, the Potzberg and the Donnersberg can be seen. To the west is a broad view into the Saarland. Almost everywhere on the south slopes of this ridge, which falls off by up to 250 m, and in places at an angle of up to 40°, are beech and spruce forests. Here and there grow gnarled oaks, birches, larches and pines. Growing on the moister brook banks are alders, willows and poplars. The plateaux, the north slope and the Pfeffelbach valley are almost wholly given over to cropraising. On the south slope, this is not possible because of the steep slope and the strong runoff that comes whenever it rains. The valleys of the south slope are heavily worn with ravines. The brooks are still wearing the hills away now, which can be observed particularly during the wintertime rainy period. The mountain crest forms the watershed between the Nahe and the Glan. The municipal area measures 386 ha, of which 177 ha is wooded.[2]

Neighbouring municipalities

Reichweiler borders in the north on the municipality of Eckersweiler, in the east on the municipality of Pfeffelbach and in the south and west on the municipality of Freisen in the Saarland.

Municipality’s layout

Reichweiler is today, like most of the other villages in the area, a typical residential bedroom community. Major commercial enterprises are not to be found in Reichweiler, nor are independent farmers. Agriculture is nowadays only ever pursued as a secondary occupation, or simply for the farmer’s own needs. Formerly, the village was purely a farming village, later growing, particularly after the Second World War, into a “worker-farmer” village, the result of an economic and social restructuring that was not without consequences for the appearance of the village’s buildings and houses. The old, former village core may be described as a typical clump village suited to its municipal area, a tight, built-up village with an irregular footprint and farms of various sizes. Most of the shorter streets, owing to the slopes, run parallel to either side of Hauptstraße (“Main Street”), which winds its way from north to south. The village’s typical building form was the Einfirsthaus (“house with single roof ridge”, typical of farmhouses in the Westrich). In one of these, the dwelling, the stable and the barn were all found under one roof. Sometimes the gables were set at the front and back, and other times at each side. This resulted in a living streetscape. The farmhouses, though, have mostly lost their agricultural function. The now unneeded commercial spaces in them have now been given over to other functions. The conversions thus brought about often left the beauty and originality that had once been typical of the region by the wayside, which adversely affected the village’s appearance. This became all the more so when in the early 1950s, in Reichweiler too, the uniform private-home building style set in. Diversity gave way to simplicity, harmony to monotony, curves to right angles. Besides the single-family houses built haphazardly in the old village core, Reichweiler has a new building zone, begun in 1965, with three phases, named Bruchwasem. A new building plan, called “Bangertstraße Südwest” is currently being considered.[3]

History

Antiquity

The area around Reichweiler has been settled since ancient times. Archaeological finds from prehistoric times bear witness to this. A ploughshare from the New Stone Age, some 4,000 years old, found within neighbouring Schwarzerden’s limits, is a particularly fine example. Frequent finds from early La Tène times and the time of the Treveri (a people of mixed Celtic and Germanic stock, from whom the Latin name for the city of Trier, Augusta Treverorum, is also derived) within Schwarzerden’s or Reichweiler’s limits behind the Mithraic monument, mainly in the shape of urns, human remains and wartime equipment such as sword tips, shield bosses and items for daily needs, even if they are not well preserved, show that the land was settled by more or less sedentary people in those days. More light is shed into the shadows of the past by the many finds from Roman times that have been unearthed in the same lands as the prehistoric finds. A stone figure depicting the Roman smith god Vulcan can now be found in the Saarländisches Landesmuseum (State Museum) in Saarbrücken. Terra sigillata vessels, clay jars, a wine ladle and the like were found during digging work in the 1920s and 1930s. Given that the cult was never thoroughly widespread in Roman times (about the 1st century AD), even though soldiers in Roman legions adopted it and spread it far into the west from its eastern origins, the Mithraic monument (Mithrasdenkmal) represents a peculiarity. It is a religious icon that was originally part of a temple in a Roman settlement. Riding on a fleeing bull is the Persian god and personification of heavenly light, Mithra, stabbing the bull in the neck, accompanied by a lion, a dog, a snake and a scorpion. Above in a semicircular arch are the sun god and the moon goddess. The youngling killing the bull stands between the god of everlasting light, Ahuramazda (the figure with the upraised torch), and the god of darkness, Ahriman (the figure with the lowered torch), at least according to Mithraic researchers and interpreters of this cult. Similarities to Christianity are unmistakable. Further, it should be mentioned that these rich finds have come from both Celtic and Roman times, and that they, along with the Mithraic monument, were originally grouped into the municipality of Schwarzerden, but owing to an arbitrary boundary adjustment, perhaps in the Middle Ages, they have found themselves within Reichweiler. The current boundary between the two is the river formerly known as the Weißwieserbach, now known as the Pfeffelbach.[4]

Middle Ages

The Frankish kings divided their empire into Gaue (roughly “shires”), and each Gau was headed by a Gaugraf, or Gau count. Several Gaue would be united into a province or a duchy. The village of Reichweiler lay right at the borders of two duchies and four Gaue. It belonged to the Nahegau in the Duchy of Franconia. It might therefore be assumed that Reichweiler belonged to the County of Veldenz. However, one of the earliest first documentary mentions, from 1273, witnesses that the local lords were the Counts of Blieskastel. How this came about is not witnessed in any document, but perhaps it might be explained in the following way: Once the Roman money-based economy had been replaced by the Germanic subsistence economy, the only thing that promised wealth and power was landholds. Land, however, was wanted not only by secular lords, but also by the now blossoming Church. It is thus no wonder that the local area had both ecclesiastical and secular territories. Most of it belonged to ecclesiastical lordships, which nevertheless ceded their holdings as fiefs or Vogteien to secular lords. The ecclesiastical lordships that earned the greatest importance in the Reichweiler area were the Archbishopric of Reims (particularly the Remigiusland) and the Bishopric of Verdun. Belonging to the latter was Tholey Abbey, which had landholds over a broad area. One of the oldest documents from early Frankish times is one from 20 December 634. Paulus, the Abbot of Tholey Abbey and Saint Wendelin’s successor, became Bishop of Verdun in 631. Bequeathed to him by the Frankish nobleman Adalgisel Grimo were great landholds around Tholey and the broader area (Sankt Wendel, Baumholder), which were entrusted to the Episcopal Church of Verdun. It may well be that these landholds contained the village of Reichweiler with its municipal area. Besides the ecclesiastical territories, a great many secular lordly territories formed over the centuries. The most important two for Reichweiler were the County of Veldenz and the County of Blieskastel. After the partitions of 843 and 870 grouped the ecclesiastical territories of Reims and Verdun in the Westrich into the German Empire, secular lords in the neighbouring lands tried to take over the episcopal land. By sale and partition (Nahegau Count Emich V’s two sons, Emich VI and Gerlach divided the Verdun fief and the Remigiusland between themselves between 1112 and 1146), the Remigiusland passed as a fief to Count Gerlach I of Veldenz. Reichweiler, which lay in the border area with the old Verdun holding, may well have been ceded to the Counts of Blieskastel. This would be the only way to explain how in 1273, Countess Elisabeth of Blieskastel and Bitsch donated the village of Reichweiler (and likewise Bubenhausen, nowadays a constituent community of Zweibrücken) along with its appurtenances to the Wörschweiler Monastery. An important day for Reichweiler was 26 May 1462 (“the day after Saint Urban’s Day”). It was then that the lord of the court, “Herr Niclassen, Apten zu Werßweiller (Wörschweiler), zu Reichwiller (Reichweiler)” handed down at a session of his court a Weistum (cognate with English wisdom, this was a legal pronouncement issued by men learned in law in the Middle Ages and early modern times). It dealt with, among other things, the court district’s boundaries, the court lord’s rights and authority, misdeeds and their penalties. Even after Countess Elisabeth of Blieskastel had donated ownership of Reichweiler to the monastery, transfers of goods to the Wörschweiler Monastery were still taking place. One such transfer was made by an association of heirs on 16 May 1303 (18 persons were named, total area 50 Fuß, price 45 shillings in Hellers) and another was made in 1421 by a married couple. The occupants of the monastery, which lay at least 35 km away (as the crow flies) could not work all their holdings in Reichweiler by themselves; so they enfeoffed others with them. Thus, on 29 August 1431, “Henichin Wolf von Spanheim vom Grafen Friederich v. Veldentzen” received, among other things, “half the holdings, the inheritance and the people at Richwilr”, only to pledge this landhold back to the monastery only two days later. Seven years later, on 2 October 1438, it was sold to the Counts of Veldenz. Even common (that is, not noble) fiefholders are named, for example the Amtmann from Sankt Wendel Peter Glock (1500), Georg Trompeter (1527) and Urban Zol (1541).[5]

Modern times

Tholey Abbey, too, had landholds in Reichweiler. On 29 May 1700, Tholey Abbey acquired certain tithes at Reichweiler from a Lord of Günderode, a Palatinate-Zweibrücken Amtmann who lived at Castle Lichtenberg. After the seemingly thoroughly confusing ownership arrangements discussed above, the arrangements in the time that followed were rather less tangled. After the Werschweiler Monastery (today known as Wörschweiler) was dissolved, Reichweiler was grouped into the Oberamt of Lichtenberg in the Duchy of Palatinate-Zweibrücken, within which it formed part of the Niederamt or Schultheißenamt of Konken.[6]

Recent times

In 1792, a French Revolutionary army, led by Adam Philippe, Comte de Custine, thrust its way into the Palatinate. Later that same year, the French also occupied the Oberamt of Lichtenberg. On 23 January 1798, the lands on the Rhine’s left bank were newly subdivided on the French model. Thereafter, Reichweiler belonged to the Mairie (“Mayoralty”) of Bourglichtenberg, the Canton of Coussel (Kusel), the Arrondissement of Birkenfeld and the Department of Sarre. The Revolutionary, later Napoleonic, French were eventually driven out. On 12 January 1814, under the Basel Resolution, the victorious powers established a joint administration under which Reichweiler belonged to the General Government of Middle Rhine (Mittelrhein) and the Department of Saar, whose seat was at Trier, and later Koblenz. This was changed on 30 May 1814 under the terms of the Treaty of Paris. Reichweiler, along with the whole of the area on the Moselle’s right bank, was made subject to the Austrian-Bavarian State Administration Commission, whose seat was at Kreuznach, and later Worms. With the Congress of Vienna came a new territorial order. For a short time (16 June 1815 to 3 November 1815), Reichweiler, among other places, was assigned to the Kingdom of Prussia, but on the condition that an area containing 69,000 souls be ceded from the former Department of Saar to leaders of lesser states. On 11 September 1816, Reichweiler thus passed to the Principality of Lichtenberg (which was given this name on 6 March 1819), a newly created exclave of the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, which as of 1826 became the Duchy of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Reichweiler belonged to the Amt of Burglichtenberg, which was united with the Amt of Berschweiler on 1 October 1822, in the Canton of Baumholder. As part of this state, it passed by sale under the terms of a treaty – the price received by the little loved ruler, Duke Ernst, was 2,100,000 Thaler – on 31 May 1834 (with effect from 22 September 1834) to the Kingdom of Prussia, which made this area into the Sankt Wendel district within the Rhine Province. This district was grouped into the Regierungsbezirk of Trier. Later, after the First World War, the Treaty of Versailles stipulated, among other things, that 26 of the Sankt Wendel district’s 94 municipalities had to be ceded to the British- and French-occupied Saar in 1919. The remaining 68 municipalities then bore the designation “Restkreis St. Wendel-Baumholder”, with the first syllable of Restkreis having the same meaning as in English, in the sense of “left over”. The district seat was at Baumholder. Reichweiler belonged to the Restkreis until 1 April 1937, when it was transferred to the Birkenfeld district. This was created by uniting the Restkreis with a hitherto Oldenburg district of that same name. The new, bigger district was grouped into the Prussian Regierungsbezirk of Koblenz. Its seat was at Birkenfeld. In the course of administrative restructuring in Rhineland-Palatinate in 1969, Reichweiler was transferred, this time to the Kusel district, in which it remains today. It also lies within the Verbandsgemeinde of Kusel, and until its abolition in 2000, it also lay in the Regierungsbezirk of Rheinhessen-Pfalz.[7]

Population development

In 1609, Reichweiler had 68 inhabitants, 13 men, 16 women, 2 menservants, 3 maidservants and 34 children. In 1675 there were five families, and in 1772 there were 28. In 1816 there were 227 inhabitants, and beginning in this time, a steady rise in population could be noted. Between 1945 and 1958, Reichweiler absorbed 15 refugees and 11 evacuees.

The following table shows Reichweiler’s population statistics since 1830:[8]

| Year | Total | Male | Female | Evangelical | Catholic | Irreligious | No answer |

| 1830 | 283 | 141 | 142 | 189 | 94 | – | – |

| 1843 | 291 | 134 | 157 | 202 | 89 | – | – |

| 1965 | 507 | 247 | 260 | 359 | 148 | – | – |

| 1999 | 602 | 295 | 307 | 412 | 163 | 11 | 16 |

The following table shows population development over the centuries for Reichweiler (“F” denotes number of families):[9]

| Year | 1608 | 1675 | 1772 | 1816 | 1830 | 1861 | 1871 | 1895 | 1939 | 1950 | 1965 | 1999 |

| Total | 68 | 5F | 28F | 227 | 283 | 337 | 360 | 376 | 392 | 423 | 507 | 602 |

Municipality’s name and vanished villages

The village’s name, Reichweiler, has the common German placename ending —weiler, which as a standalone word means “hamlet” (originally “homestead”), to which is prefixed a syllable Reich—, believed to have arisen from a personal name, Richo, suggesting that the village arose from a homestead founded by an early Frankish settler named Richo, thus “Richo’s Homestead”. The village’s founding did take place sometime during the Frankish takeover of the land. The ending —weiler arose from the old Roman country estates, known in Latin as villae rusticae, but in fact it is derived from the Late Latin word villare, a verb meaning “to dwell”. Such villae rusticae are known to have existed in the immediate vicinity (in Freisen and Thallichtenberg, both neighbouring villages), while another neighbour, Schwarzerden, was a major Roman settlement. Further bolstering this interpretation are the great many —weiler villages in the immediate area. Even the vanished villages that once stood within Reichweiler’s limits were both examples. They were called Gerweiler, which lay at the municipal limits with Oberkirchen and Freisen, and Würzweiler, on whose site now lies a new building area. Rural cadastral toponyms still recall these places.[10]

Religion

The Reichweiler dwellers’ ecclesiastical life might have been defined by either Tholey Abbey’s or the Wörschweiler Monastery’s ownership. Very early on, certainly before 1559, Reichweiler had a chapel. Bearing witness to its location now is only a rural cadastral toponym, “hinter der Kirch” (“Behind the church”). In 1570, the village council at Reichweiler wrote to the Prince at Zweibrücken telling him that their chapel had already been in disrepair for many years. Likewise very early on, the Reformation was introduced into the Duchy of Palatinate-Zweibrücken. The Protestants found a keen champion for their cause in Duke Wolfgang. It was he who brought about the ecclesiastical visitations. One such event took place in Reichweiler in 1565. Hitherto, Reichweiler had still been parochially united with Ketternostern (now part of Oberkirchen, itself now part of Freisen). In May 1566, a circular came forth from the councillors at Zweibrücken to the state scrivener at Lichtenberg in which the subjects were ordered henceforth to belong to the parish of Pfeffelbach. Since this time, Reichweiler’s Evangelical inhabitants have belonged to Pfeffelbach, while the Catholic ones have belonged to Oberkirchen. Only since 1851 has Reichweiler had its own graveyard. Before this, the dead were taken over the so-called Leichenweg (literally “Dead Body Way”; now a rural cadastral toponym) to Pfeffelbach to be buried at the graveyard there.[11]

Politics

Municipal council

The council is made up of 12 council members, who were elected by majority vote at the municipal election held on 7 June 2009, and the honorary mayor as chairman.[12]

Mayor

Reichweiler’s mayor is Bernd Hoffmann, and his deputies are Arnold Schmitt and Stefan Becker.[13]

Coat of arms

The German blazon reads: Von Silber und Rot geteilt, oben ein wachsender, rotbewehrter und -bezungter, blauer Löwe, unten eine runde, goldene Scheibe, darin ein schwarzer Dolch über einem Paar schwarzer Stierhörner.

The municipality’s arms might in English heraldic language be described thus: Per fess argent a demilion azure armed and langued gules and gules a bezant surmounted by a dagger palewise over a bull’s attires, both sable.

The charge in the upper field is the Veldenz lion. Reichweiler, if it ever did belong to the County of Veldenz, only did so for a short time, but this charge was nonetheless included in the coat of arms because every municipality in the Amt Burglichtenberg in Berschweiler (Birkenfeld district), to which Reichweiler belonged at the time, assumed this same charge, and because the Veldenz lion also appeared in the arms borne by the Dukes of Palatinate-Zweibrücken (Reichweiler belonged to Palatinate-Zweibrücken from 1559 to 1793). The combination of charges in the lower field is meant to represent the sun god’s symbol found at the Mithraic monument (Mithrasdenkmal) in the municipality. The arms have been borne since 13 January 1964 when they were approved by the Rhineland-Palatinate Ministry of the Interior.[14]

Culture and sightseeing

Buildings

The following are listed buildings or sites in Rhineland-Palatinate’s Directory of Cultural Monuments:[15]

- Schulstraße 7 – former school; corner building on rusticated-block pedestal, half-hipped roof, about 1910

- Near Schulstraße 7 – warriors’ memorial for the fallen of the First World War; expanded for the fallen of the Second World War, heroes’ grove with soldier, possibly from the 1930s, name plaques from the 1950s

- Mithras cult icon, near Schwarzerden on Landesstraße 349 – high relief, possibly from the 3rd century, protective building from 1874

Regular events

Wannerschdag

Still observed among old customs in Reichweiler is the Wannerschdag (in standard German, Wanderstag, or “Hiking Day”). This is done on Boxing Day (26 December), when young and old alike hike in groups at various compass headings, mostly arriving in a neighbouring village, where they visit an inn to refresh themselves with food and drink. In the evening, they all meet at Reichweiler’s last remaining public house. Here, the mayor then lays down his accounting report, accompanied for a time with a meal of mutton, which is (or was) laid on by the Jagdpächter (a hunter who holds/held hunting rights as a tenancy). The custom goes back to an older one in which menservants and maidservants changed employers on this day.[16]

Shrovetide Carnival

Fastnacht (Shrovetide Carnival) is celebrated as it is in the surrounding villages, and no Shrovetide lunchtime table in Reichweiler would be complete without Fastnachtskiechelcher, a pastry made of flour, vanilla sugar, sugar, yeast, milk, butter, salt and eggs.[17] There are also dancing events held on various evenings during Shrovetide.[18]

Whitsun

Worth mentioning here is the old custom of the Pfingstquack on the second day of Whitsun (this is still practised, with variations, in some of the district’s villages; see Henschtal for more). Whitsun is called Pfingsten in German, partly explaining the custom’s name; the —quack part of the name refers to a rhyme that the children recite as they go door to door begging for money with their gorse-decked wagon. The rhyme generally begins with the line “Quack, Quack, Quack”.[19][20]

Kermis

Reichweiler holds its kermis (church consecration festival, locally known as the Kerwe) on the second Sunday after Michaelmas (29 September).[21]

Martinmas

Reichweiler celebrates the festivities of Martinmas or Saint Martin’s Day (11 November) together with the municipality of Pfeffelbach.[22]

May Day

May Day is celebrated with a May Fire on the eve of 1 May (Walpurgis Night) at the Fuzzy Ranch (so-called even in German, this is actually a cabin built by the village youth at the foot of the Karrenberg, similar to ones built by the Pfälzerwaldverein, a Palatine hiking club, but meant foremost for Reichweiler locals). Open-air festivals have also been held here for the general public for some years now.[23]

Clubs

Reichweiler’s clubs are quite lively in the amount of activity in which they engage. Among the village’s other clubs are the following:[24]

- Angelsportverein Reichweiler-Schwarzerden – angling club

- Ev. Frauenhilfe – Evangelical Women’s Aid

- Landfrauenverein – countrywomen’s club

- Sängergruppe – singers’ group

- Sportverein mit Sportplatz und Tennisanlage – sport club with sporting ground and tennis facility

- Teufelskopf-Wanderer – hiking club

Economy and infrastructure

Education

It was only beginning in the Reformation that serious thought was devoted to schools. The funds earned from the dissolution of monasteries, among them Wörschweiler in 1559, were used by Duke Wolfgang to found schools and to better pastoral posts. The children’s first schooling as a rule came from the pastor. Protestant teaching was to come to them through the Bible, the hymnal and the Catechism. Thus, the first parochial schools arose at clergymen’s seats. In 1592, the clergyman in Pfeffelbach received an order from the Duke to hold school for children from not only Pfeffelbach, but also Reichweiler and Schwarzerden, which likewise belonged to his parish. It may make for curious reading that a village councillor named Simon Brill was suspended from school service (this after his predecessor Pastor Pfeil had decided in 1651 that he was tired of school work) because it turned out that he himself could neither read nor write, or that Johann Fischer Barthel had to leave his post in 1663 because the village’s elderly inhabitants feared that the children were becoming cleverer than they were. Oftentimes, the teaching post at the winter school (a school geared towards an agricultural community’s practical needs, held in the winter, when farm families had a bit more time to spare) was left vacant. Among other reasons for this were a teacher’s failure to secure a guarantee of freedom from compulsory labour, overdue wages, the need to pay a herdsman’s fee, and so on. In November 1749, a new phase in schooling began for Reichweiler’s schoolchildren. It was then that two municipalities within the parish of Pfeffelbach, namely Reichweiler and Schwarzerden, were granted leave to set up their own winter school. The classes were held at private houses, alternating each year between the two villages. The move to the other venue, which involved transferring some equipment, was done each year at Candlemas (2 February). The schoolteacher Johann Adam Decker was teaching 23 schoolchildren in 1792 at the Reichweiler/Schwarzerden winter school. The subjects that were taught were religion, reading, writing, spelling, grammar, organ playing, keeping school and silkworm raising. Later, geometry was added. Another schoolteacher named Decker, who had been appointed by the Ducal Saxe-Coburg and Gotha government in 1833, received as remuneration 110 Thaler in 1851, 140 Thaler in 1855 and 160 Thaler in 1866. His pension in 1871 was 60 Thaler. On 1 May 1871, the Reichweiler-Schwarzerden school association was dissolved and each municipality got its own school. Reichweiler’s Catholic schoolchildren had until 1814 attended the school in Oberkirchen. Work on the Reichweiler elementary school (Volksschule) began in 1908. It had one class, sometimes with as many as 90 pupils. It was split into two classes from 1 February 1931 to 30 November 1938 and again as of 1 April 1957. The following table shows the number of schoolchildren in Reichweiler at various times, broken down by religious denomination:

| Year | Evangelical | Catholic | Total |

| 1898 | 34 | 23 | 57 |

| 1910 | 45 | 21 | 66 |

| 1966 | 41 | 23 | 64 |

At the beginning of the 1970/1971 school year, the Reichweiler elementary school was integrated into the Pfeffelbach elementary school, thus losing its independent existence. Today, Hauptschule students attend classes in Kusel while primary school pupils attend school in Pfeffelbach.[25]

Public institutions

For a short time in the 1960s, Reichweiler had a municipal library, but it turned out that there was little demand for it. Otherwise, it has been the cultural facilities in both the nearer and farther neighbouring area that have been used (Kusel, Sankt Wendel, Kaiserslautern, Saarbrücken).[26]

Transport

To the south lies the Autobahn A 62 (Kaiserslautern–Trier) with an interchange in the municipality.

Telecommunications

At 49°33′10″N 7°17′59″E / 49.55278°N 7.29972°E stands a 137 m-high transmission tower run by Deutsche Telekom AG, which like the nearby one on the Bornberg is a standard design of the type FMT 16.

References

- ↑ "Gemeinden in Deutschland mit Bevölkerung am 31. Dezember 2015" (PDF). Statistisches Bundesamt (in German). 2016.

- ↑ Location

- ↑ Municipality’s layout

- ↑ Antiquity

- ↑ Middle Ages

- ↑ Modern times

- ↑ Recent times

- ↑ Reichweiler’s population development

- ↑ Reichweiler’s population development

- ↑ Municipality’s name

- ↑ Religion

- ↑ Kommunalwahl Rheinland-Pfalz 2009, Gemeinderat

- ↑ Reichweiler’s council

- ↑ Description and explanation of Reichweiler’s arms

- ↑ Directory of Cultural Monuments in Kusel district

- ↑ Wannerschdag

- ↑ Recipe for Fastnachtskiechelcher

- ↑ Shrovetide Carnival

- ↑ The Pfingstquack explained

- ↑ Whitsun

- ↑ Kermis

- ↑ Martinmas

- ↑ May Day

- ↑ Clubs

- ↑ Education

- ↑ Public institutions

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Reichweiler. |