Royal Sovereign-class battleship

.jpg) The high-freeboard Royal Sovereign underway in a moderate sea | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Royal Sovereign class |

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | Trafalgar class |

| Succeeded by: | Centurion class |

| Subclasses: | Hood |

| Built: | 1889–94 |

| In commission: | 1892–1915 |

| Completed: | 8 |

| Retired: | 2 |

| Scrapped: | 6 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | 14,150 long tons (14,380 t) (normal) |

| Length: | 380 ft (115.8 m) (pp) |

| Beam: | 75 ft (22.9 m) |

| Draught: | 27 ft 6 in (8.4 m) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | 2 shafts; 2 Triple-expansion steam engines |

| Speed: | 17.5 knots (32.4 km/h; 20.1 mph) |

| Range: | 4,720 nmi (8,740 km; 5,430 mi) @ 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement: | 670–692 |

| Armament: |

|

| Armour: |

|

The Royal Sovereign class was a group of eight pre-dreadnought battleships built for the Royal Navy in the 1890s. The ships spent their careers in the Mediterranean, Home and Channel Fleets, sometimes as flagships, although several were mobilised for service in 1896 with the Flying Squadron when tensions with the German Empire were high.

By about 1905–07, they were considered obsolete and were reduced to reserve. The ships began to be sold off for scrap beginning in 1911, although Empress of India was sunk as a target ship during gunnery trials in 1913. Hood was fitted with the first anti-torpedo bulges to evaluate underwater protection schemes in 1911 before being scuttled as a blockship a few months after the start of the First World War in August 1914. Only Revenge survived to see active service in the war, during which she bombarded the Belgian coastline. Renamed Redoubtable in 1915, she was hulked later that year as an accommodation ship until she was sold for scrap after the war.

Background

By the late 1880s pressure on the government to modernise and expand the Royal Navy was building. A war scare with Russia in 1885 during the Panjdeh Incident, various official reports on training exercises and the characteristics of ships, coupled with exposés by influential journalists like W. T. Stead, revealed serious weaknesses in the Navy. The Government responded with the Naval Defence Act 1889, which provided £21.5 million for a vast expansion programme of which the eight ships of the Royal Sovereign class were the centrepiece. The Act also formalised the two-power standard, whereby the Royal Navy sought to be as large as the next two major naval powers combined.[1]

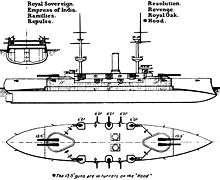

Preliminary work on what would become the Royal Sovereigns began in 1888 and the Board of Admiralty directed the Director of Naval Construction, Sir William White, to design an improved and enlarged version of the Trafalgar class. These ships were equipped with gun turrets, the weight of which dictated that they be low-freeboard ships to reduce their topweight. White, however, argued strenuously for a high-freeboard design to improve the new ships' ability to fight and steam in heavy weather. This meant that the armament could only be mounted in lighter, less-heavily armoured barbettes. After much discussion, the board came around to White's view and the design resembled an enlarged version of the earlier Admiral class, although one of the eight ships, Hood, was built as a low-freeboard turret ship in deference to the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Arthur Hood, who had strongly argued for the type.[2] The Royal Sovereigns are often considered the first of the type of battleship which would become known after the commissioning of the revolutionary Dreadnought in 1906 as pre-dreadnoughts.[3]

Design and description

The ships displaced 14,150 long tons (14,380 t) at normal load and 15,580 long tons (15,830 t) at deep load. They had a length between perpendiculars of 380 feet (115.8 m) and an overall length of 410 feet 6 inches (125.1 m), a beam of 75 feet (22.9 m), and a draught of 27 feet 6 inches (8.4 m).[3]

Those ships fitted with barbettes had a freeboard of 19 feet 6 inches (5.9 m) (about 90% of modern guidelines), provided by the addition of a complete extra deck, which improved their performance in heavy seas.[4] To reduce their topweight, White gave them a significant amount of tumblehome.[5] Hood's freeboard, however, was only 11 feet 3 inches (3.4 m), which meant that she was very wet and lost speed rapidly as wave height increased. She was the last British battleship with the heavy, old-style, turrets and all future British battleships were of a high-freeboard design and had their main armament in barbettes, although the adoption of armored, rotating gunhouses over the barbettes gradually led to them being called "turrets" as well.[6]

_LOC_16922u.jpg)

Another issue with Hood was that the stability of a ship is largely due to freeboard at high rolling angles, so she had to be given a larger metacentric height (the vertical distance between the metacenter and the centre of gravity below it) of around 4.1 feet (1.2 m) instead of the 3.6 feet (1.1 m) of the rest of the Royal Sovereigns to make her roll less in rough seas. This had the effect of making her roll period shorter by around 7% compared to her sisters, which in turn made her gunnery less accurate. White had purposely selected a high GM to minimise rolling and he did not think that bilge keels were needed. When Resolution experienced heavy rolling during a heavy storm in December 1893, which earned the class the nickname Rolling Ressies, her sister ship, Repulse, was fitted with bilge keels while still fitting out and conclusively demonstrated their effectiveness during comparative trials. The rest of the ships were fitted with bilge keels in 1894–95.[7]

The Royal Sovereigns were powered by a pair of three-cylinder, vertical triple-expansion steam engines, each driving one propeller shaft, using steam provided by eight cylindrical boilers that operated at a pressure of 155 psi (1,069 kPa; 11 kgf/cm2).[8] The engines were designed to produce a total of 9,000 indicated horsepower (6,700 kW) at normal draught and a speed of 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph); using forced draught, they were expected to produce 11,000 ihp (8,200 kW) and a maximum speed of 17.5 knots (32.4 km/h; 20.1 mph). The Royal Sovereign-class ships comfortably exceeded these speeds; Royal Sovereign herself reached 16.43 knots (30.43 km/h; 18.91 mph) from 9,661 ihp (7,204 kW) with natural draught. Trials at forced draught, however, damaged her boilers, although the ship attained 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) from 13,360 ihp (9,960 kW). As a result, the Navy decided not to push the boilers of the Royal Sovereign class past 11,000 ihp to prevent similar damage. The ships carried a maximum of 1,420 long tons (1,443 t) of coal, which gave them a range of 4,720 nautical miles (8,740 km; 5,430 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[9]

Armament and armour

A new and more powerful 12-inch (305 mm) gun was preferred by the Board, but it was still under development, so the BL 13.5-inch (343 mm) 67-ton gun used in the preceding classes was chosen.[10] The four guns were mounted in two twin-gun, pear-shaped barbettes or circular turrets, one forward and one aft of the superstructure. The barbettes were open, without hoods or gun shields, and the guns were fully exposed. The ammunition hoists were in the apex of the barbette and the guns had to return to the fore-and-aft position to be reloaded.[5] The 1,250-pound (570 kg) shells fired by these guns were credited with the ability to penetrate 28 inches (711 mm) of wrought iron at 1,000 yards (910 m), using a charge of 630 pounds (290 kg) of smokeless brown cocoa (SBC).[11] At maximum elevation of +13.5°, the guns had a range of around 11,950 yards (10,930 m) with SBC; later a charge of 187 pounds (85 kg) of cordite was substituted for the SBC which extended the range to about 12,620 yards (11,540 m).[12] The ships carried 80 rounds for each gun.[10]

The secondary armament of ten quick-firing (QF) 6-inch (152 mm) guns was a significant upgrade over the six QF 4.7-inch (120 mm) guns of the Trafalgar class. These guns were intended to destroy the unarmoured structure of their opponents and they were widely spaced on two decks so that a single hit would not disable more than one. Four of the guns were situated on the main deck and were only usable in calm weather, while the remaining guns were above them on the upper deck. Together with their ammunition supply of 200 rounds per gun, the guns weighed about 500 long tons (508 t) and were one of the reasons for the large increase in displacement over the earlier ships.[13] The guns fired their 1,000-pound (450 kg) shells to a range of 11,400 yards (10,400 m) at their maximum elevation of +20°.[14] Sixteen QF 6-pounder (2.2 in (57 mm)) and a dozen QF 3-pounder (1.9 in (47 mm)) Hotchkiss guns were fitted for defence against torpedo boats. The Royal Sovereign-class ships also mounted seven 14-inch (356 mm) torpedo tubes, two submerged and four above water on the broadside, plus one above water in the stern.[15]

The Royal Sovereigns' armour scheme was similar to that of the Trafalgars, as the waterline belt of compound armour only protected the area between the barbettes. The 14–18-inch (356–457 mm) belt was 250 feet (76.2 m) long and had a total height of 8 feet 6 inches (2.6 m) of which 5 feet (1.5 m) was below water. Transverse bulkheads 16 inches (406 mm) (forward) and 14 inches (aft) thick formed the central armoured citadel. Above the belt was a strake of 4-inch (102 mm) armour, backed by deep coal bunkers, that was terminated by 3-inch (76 mm)[3] oblique bulkheads that connected the upper side armour to the barbettes. The plates of the upper strake were Harvey armour only inRoyal Sovereign; her sisters had nickel steel, although Hood's plates were 4.375 inches (111 mm) thick.[16]

The barbettes and gun turrets were protected by compound armour, ranging in thickness from 16 to 17 inches (406 to 432 mm) and the casemates for the main deck 6-inch guns had a thickness equal to their diameter. The ammunition hoists to the main deck secondary guns were 2 inches (51 mm) thick while those for the upper deck guns were twice that. The submerged armour deck was 3 inches thick amidships and reduced to 2.5 inches (64 mm) towards the ends of the ship; the forward end curved downwards to reinforce the plough-shaped ram. The walls of the forward conning tower were 12–14 inches (305–356 mm) thick and the communications tube that ran down to the armour deck was 8 inches (203 mm) in thickness. The aft conning tower was protected by 3-inch plates, as was its communication tube. Between 1902 and 1904, the thin gun shields protecting the upper deck 6-inch guns were replaced by armoured casemates in all the ships except Hood, whose lack of stability prevented the addition of such weights high in the ship.[17]

Ships

| Ship | Builder | Laid down[18] | Launched[18] | Completed[18] | Cost (including armament)[19] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Royal Sovereign | Portsmouth Dockyard | 30 September 1889 | 26 February 1891 | May 1892 | £913,986 |

| Empress of India | Pembroke Dockyard | 9 July 1889 | 7 May 1891 | 11 September 1893 | £912,162 |

| Repulse | 1 January 1890 | 27 February 1892 | 25 April 1894 | £915,302 | |

| Hood | Chatham Dockyard | 12 August 1889 | 30 July 1891 | May 1893 | £926,396 |

| Ramillies | J & G Thomson, Clydebank | 11 August 1890 | 1 March 1892 | 17 October 1893 | £980,895 |

| Resolution | Palmers, Jarrow | 14 June 1890 | 28 May 1892 | 5 December 1893 | £953,817 |

| Revenge | 12 February 1891 | 3 November 1892 | 22 March 1894 | £954,825 | |

| Royal Oak | Cammell Laird, Birkenhead | 29 May 1890 | 5 November 1892 | 12 June 1894 | £977,996 |

Operational history

The ships spent their lives in the routine of the Victorian Royal Navy, participating in annual manoeuvres and occasional fleet reviews from their commissioning until the early 1900s. All saw service in home waters and Revenge and Royal Oak were temporarily assigned to the Particular Service Squadron in 1896. Many also served in the Mediterranean, where Empress of India and Revenge were assigned to the International Squadron blockading Crete during the uprising there in 1897–98. The class generally went into the commissioned reserve around 1905.[20]

In 1906, the Royal Sovereigns, like every other battleship in the world, were made obsolete with the launch of the revolutionary Dreadnought, the first all-big-gun battleship. They were consigned to less critical duties for the remainder of their service life, and began to appear on the disposal list in 1909.[20] Only two ships survived to see the outbreak of war in 1914, one of them (Hood) quickly being sunk as a blockship. Only one, Revenge (renamed Redoubtable in 1915), saw action in World War I, bombarding the coast of Belgium in 1914 and 1915 before decommissioning.[21]

Royal Sovereign was commissioned in 1892 and served as the flagship of the Channel Fleet for the next five years. She was transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet in 1897 and returned home in 1902, and was briefly assigned as a coast guard ship before she began a lengthy refit in 1903–04. Royal Sovereign was reduced to reserve in 1905 and was taken out of service in 1909.

Hood served most of her active career in the Mediterranean Sea, where her low freeboard was less of a disadvantage. The ship was placed in reserve in 1907 and later became the receiving ship at Queenstown, Ireland. Hood was used in the development of anti-torpedo bulges in 1911–13 and was scuttled in late 1914 to act as a blockship across the southern entrance of Portland Harbour.

Empress of India was commissioned in 1893 and served as the flagship of the second-in-command of the Channel Fleet for two years. She was transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet in 1897. She returned home in 1901 and was briefly assigned as a coast guard ship in Ireland before she became the second flagship of the Home Fleet. The ship was reduced to reserve in 1905 and accidentally collided with the submarine HMS A10 the following year. Empress of India was taken out of service in early 1912 and accidentally struck a German sailing ship while under tow. She was sunk as a target ship in 1913.

Ramilles served in the Mediterranean Fleet (1893–1903), Reserve Fleet (1903–1907), and Home Fleet (1907–1911), and was scrapped in 1913.[22]

Repulse Assigned to the Channel Fleet, where she often served as a flagship, after commissioning in 1894, the ship participated in a series of annual manoeuvres, and the Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee Fleet Review during the rest of the decade. Repulse was transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet in 1902 and remained there until December 1903, when she returned home for an extensive refit. After its completion in 1905, Repulse was assigned to the Reserve Fleet until she was sold for scrap in 1911.

Resolution served in the Channel Fleet (1893–1901), then in various subsidiary and commissioned reserve duties until decommissioned in 1911 and scrapped in 1914.[22]

Revenge was placed in reserve upon her return home in 1900 and was then briefly assigned as a coast guard ship before she joined the Home Fleet in 1902. The ship became a gunnery training ship in 1906 until she was paid off in 1913. The ship was recommissioned the following year, after the start of World War I, to bombard the coast of Flanders as part of the Dover Patrol, during which she was hit four times, but was not seriously damaged. She had anti-torpedo bulges fitted in early 1915, the first ship to be fitted with them operationally.[23] The ship was renamed Redoubtable later that year and was refitted as an accommodation ship at the end of the year. The last surviving member of her class, the ship was sold for scrap in November 1919.

Royal Oak served in the Mediterranean Fleet (1897–1902), Home Fleet (1903–05), Reserve Fleet (1905–07), and the new Home Fleet (1907–11), before decommissioning in 1912 and being scrapped in 1914.[22]

Notes

- ↑ Brown, pp. 115–17

- ↑ Brown, pp. 119–22; Burt, pp. 68–70; Roberts, p. 116

- 1 2 3 Chesneau & Koleśnik, p. 32

- ↑ Brown, p. 124

- 1 2 Parkes, p. 358

- ↑ Brown, p. 124; Burt, p. 101

- ↑ Brown, pp. 124–25; Burt, pp. 72–73, 75

- ↑ Parkes, p. 355

- ↑ Burt, pp. 73, 83–84

- 1 2 Burt, pp. 73, 75

- ↑ Parkes, pp. 316–17

- ↑ Campbell 1981, p. 96

- ↑ Brown, p. 123; Burt, pp. 73, 77–78

- ↑ Friedman, pp. 87–88

- ↑ Brown, p. 123; Parkes, p. 355

- ↑ Burt, pp. 79–80, 103

- ↑ Burt, pp. 79–80, 85; Parkes, p. 364

- 1 2 3 Silverstone, pp. 229, 239, 260–62, 265

- ↑ Parkes, pp. 355, 364

- 1 2 Burt, pp. 80–84

- ↑ Burt, pp. 83–84

- 1 2 3 "Royal Sovereign Class Battleship". www.worldwar1.co.uk. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- ↑ Burt, pp. 87, 90

References

- Brown, David K. (1997). Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development 1860–1905. London: Chatham. ISBN 1-86176-022-1.

- Burt, R. A. (2013). British Battleships 1889–1904. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-065-8.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1981). "British Naval Guns 1880–1945 Nos. 2 and 3". In Roberts, John. Warship V. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 96–97, 200–02. ISBN 0-85177-244-7.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860-1905. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8. OCLC 67375475.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships (reprint of the 1957 ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- Roberts, John (1992). "The Pre-Dreadnought Age 1890–1905". In Gardiner, Robert. Steam, Steel and Shellfire: The Steam Warship 1815–1905. Conway's History of the Ship. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 112–33. ISBN 1-55750-774-0.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Royal Sovereign class battleship. |