Russian interregnum of 1825

The Russian interregnum of 1825 began December 1 [O.S. November 19] with the death of Alexander I in Taganrog and lasted until the accession of Nicholas I and the suppression of the Decembrist revolt on December 26 [O.S. December 14]. In 1823 Alexander secretly removed his brother Constantine from the order of succession and appointed Nicholas heir presumptive. Unprecedented secrecy backfired with a dynastic crisis that placed the whole House of Romanov at peril. Only three men, apart from Alexander himself, were fully aware of his decision,[1] and none of them was present in the Winter Palace when the news of Alexander's death reached Saint Petersburg on December 9 [O.S. November 27] 1825.

Military governor Mikhail Miloradovich persuaded hesitant Nicholas to pledge allegiance to Constantine, who then lived in Warsaw as the viceroy of Poland. The State Council, faced with a legal Gordian Knot, concurred with Miloradovich; the civil government and the troops stationed in Saint Petersburg recognized Constantine as their sovereign – a sovereign who did not intend to reign. As The Times of London observed, the Russian Empire had "two self-denying Emperors and no active ruler".[2] Correspondence between Saint Petersburg and Warsaw, carried by mounted messengers, took two weeks. Constantine repeated his renunciation of the crown and blessed Nicholas as his sovereign but refused to come to Saint Petersburg, leaving the dangerous task of resolving the crisis to Nicholas alone.

Evidence of the brewing Decembrist revolt compelled Nicholas to act. In the first hour of December 26 [O.S. December 14] he proclaimed himself Emperor of All the Russias. By noon the civil government and most of the troops of Saint Petersburg pledged allegiance to Nicholas but the Decembrists incited three thousand soldiers in support of Constantine and took a stand on Senate Square. Nicholas crushed the revolt at a cost of 1,271 lives[3] and became an undisputed sovereign. He ruled the empire in an authoritative reactionary manner for 29 years.

The first historic study of the interregnum, Modest von Korff's Accession of Nicholas I, was commissioned by Nicholas himself. Memoirists, historians and fiction authors sought alternative explanations of the apparently irrational behaviour of the Romanovs. Conspiracy theorists named Alexander, Nicholas, Miloradovich and Empress dowager Maria, alone or in various alliances, as the driving forces behind the events of November–December 1825.

Background

Four brothers

| Four sons of Paul I | |||

|---|---|---|---|

.png) |

|

.jpg) |

|

| (1777–1825) |

(1779–1831) |

(1796–1855) |

(1798–1849) |

Alexander I of Russia, the elder of four sons of Paul I, had no male issue; his legitimate daughters died in infancy. According to the 1797 Pauline Laws his childless brother Constantine had been heir presumptive since Alexander's accession. The third brother, Nicholas, followed him in the order of succession. Constantine and his legitimate wife Juliane of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld separated in 1799. Juliane returned to Germany and resisted any proposals to restore the family. Constantine, engaged in the action of the Napoleonic Wars, did not attempt a formal divorce until meeting Joanna Grudzińska. Their love affair that began in 1815 compelled Constantine to divorce Juliane and marry Joanna.[4]

Constantine divorced Juliane in absentia on April 2 [O.S. March 20], 1820. On the same day Alexander appended the Pauline Laws with a principle that a marriage between a member of the House of Romanov and a person of lesser standing could not confer on the latter the rights of the House, and that their offspring were barred from the order of succession.[5] On May 24 [O.S. May 12] of the same year, Constantine married Joanna, who was created Duchess of Łowicz.[6] Constantine had no intention of ruling the Empire and retired to Warsaw as the viceroy of Congress Poland. According to Nicholas, Alexander told him of Constantine's decision to abdicate in 1819.[7] According to Michael, the youngest of four brothers, he learned about it from Constantine in the summer of 1821.[8] In both cases the speakers emphasized extreme secrecy of the matter.

Korff wrote that Constantine's renunciation "was completed or, at all events, received its final arrangement" in the very end of 1821 when all four brothers reunited in Saint Petersburg.[9] On January 26 [O.S. January 14], 1822 Constantine sent "a humble petition" to Alexander, expressing his wish to pass the rights to the throne to the next in line, Nicholas.[10] Two weeks later Alexander wrote to Constantine that the matter was still not resolved. The closing paragraph was especially ambiguous and could have been interpreted as leaving the final outcome in Constantine's hands: "It therefore remains to herself [Empress Maria] as well as to me ... to leave you fully at liberty to execute your irrevocable determination...".[11]

Secret manifest

_by_Gau.jpg)

In the summer of 1823 minister of Ecclesiastical Affairs Alexander Golitsyn, acting on behalf of Alexander, asked Archbishop of Moscow Filaret to draft a formal manifest that would seal the "final arrangement" made a year and a half earlier.[12] Alexander's usual speechwriter Mikhail Speransky was cut out the loop.[13] Golitsyn instructed Filaret to lock the signed manifest, in utmost secrecy, in the sanctuary of the Assumption Cathedral in Moscow.[13] Filaret feared that a document locked in Moscow could not influence the transfer of power to the successor, which would normally take place in Saint Petersburg, and objected to Alexander. The tsar reluctantly agreed and ordered Golitsyn to make three copies and deposit them in sealed envelopes in the Synod, the Senate and the State Council in Saint Petersburg.[14] Although Filaret insisted that at least the existence of these envelopes must be made known to reliable witnesses, the whole affair "has been preserved as in a tomb, the Imperial secret involving the existence of the empire".[15]

Alexander signed the manifest in Tsarskoye Selo on August 28 [O.S. August 16], 1823 and brought it to Moscow himself on September 6 [O.S. August 25].[16] According to Alexander's handwriting on the envelope it was "to be opened by the Diocesan of the See of Moscow and the General-Governor of Moscow in the cathedral of Assumption, before taking any other steps."[16] Four days later Filaret took the envelope inside the cathedral, showed Alexander's seal to three priests and locked the Manifest in the altar.[17] Governor of Moscow Dmitry Golitsyn remained unaware of the affair altogether.[18]

The "Saint Petersburg copies", handwritten by Alexander Golitsyn and bearing Alexander's own handwriting on the envelopes, were filed three months later, raising short-lived speculations among the "completely ignorant dignitaries".[15] Apart from Alexander, only Aleksey Arakcheyev, Alexander Golitsyn and Filaret were certainly aware of the existence, contents and location of the manifest and its copies.[1] According to Korff, Empress Maria was actively engaged in the events of 1821–1822 and knew of the "final arrangement"[19] but not its implementation. Constantine, Nicholas, Michael and Alexander's wife Elisabeth knew even less.[20] The reasons for unprecedented secrecy are unknown. Nicholas's bad reputation among the troops is a common explanation. Anatole Mazour wrote that Nicholas was "unacceptable to political circles and most unpleasant to military men"; as the inspector of the Guards he "aroused both the displeasures of higher officers and the hatred of the privates"; but Mazour also admitted that Constantine was "scarcely more agreeable to the military men".[21] Riasanovsky suggested that Alexander wanted to retain freedom to change the 1823 manifest at will.[22]

Conspiracy

After the end of the Napoleonic Wars the Russian economy, ravaged by the Continental System[23] and Napoleon's invasion, slid into a continuous economic crisis. Grain exports were high in 1816–1817, but in 1818–1819 Western European crops recovered and Russian exports plummeted.[24] Landed gentry tried to restore lost income through enclosures and driving away redundant serf peasants, but Alexander outlawed "emancipation" of serfs without land.[25] Economic downfall fuelled radical opposition inside Russian nobility: "it was Alexander's failures to live up to their hopes that led them to take on the task to themselves".[26]

The imperial treasury was bankrupted by rising state debt and falling revenues. Alexander was aware of the crisis but never tackled its root cause, the oversized peacetime army of 800,000 men.[27] Alexander expected future wars in Southern Europe and the Middle East,[28] and feared that mass dismissal of veteran soldiers would cause insurrection. He could not let them go: they were not needed in their native villages, and there were no jobs in the cities. Instead of reducing the army to an affordable peacetime size, Alexander tried to cut spending through the establishment of self-sustaining military settlements, which failed "from start to finish".[29] He replaced expensive field maneuvers with drill exercise and parades, alienating experienced commanders and contributing to dissatisfaction of the nobility.[30]

The first secret organization aspiring to change the system was formed by the veterans of Napoleonic Wars in February 1816.[31] Their aims varied from establishing a constitutional monarchy to "getting rid of foreigners and alien influence".[32] Some even considered murdering Alexander I after Sergey Trubetskoy reported a rumour that Alexander was planning to incorporate western provinces into Congress Poland.[33] In 1818 the organization was reformed into the Union of Prosperity. In the same year Pavel Pestel, the most radical conspirator, relocated to Ukraine and began actively recruiting Army officers, the core of the future Southern Society.[34]

In January 1821 internal conflicts between the radical South and the aristocratic North led to the dissolution of the Union of Prosperity.[35] Members of the Northern Society indulged in writing elaborate aristocratic constitutions while Pestel and his ring settled on changing the regime by military force.[36] Pestel's own political program, influenced by Antoine Destutt de Tracy, Adam Smith, Baron d'Holbach and Jeremy Bentham[37] envisioned "one nation, one government, one language" for the whole country, a uniform Russian-speaking entity with no concessions to ethnic or religious minorities, even the Finns or the Mongols.[38] Contrary to the aspirations of the Northern Society, Pestel planned to reduce the influence of landed and financial aristocracy, "the main obstacle to national welfare that could be eliminated only under a republican form of government."[39]

Pestel's influence gradually radicalized the Northern Society and helped in bringing the two groups together. Twice, in 1823 and 1824, the North and the South planned joint strikes against Alexander. The Southern terrorists subscribed to kidnap or kill Alexander during military maneuvers, the North was tasked with inciting revolt in Saint Petersburg. In both cases Alexander changed his itinerary and evaded the rebels.[40] His informers reported a fragmented picture of the conspiracy; Alexander had no secret police and managed the investigation personally on ad hoc basis.[41] Pestel's third plan shifted the center of insurgence to Saint Petersburg but the death of Alexander caught the conspirators unprepared.[42]

Death of Alexander

On September 13 [O.S. September 1], 1825[43] Alexander left Saint Petersburg to accompany the ailing Empress Elizabeth to spa treatment in Taganrog, then a "rather agreeable town"[44] on the coast of Sea of Azov. Golitsyn pleaded with Alexander to publish the secret manifest of 1823 but the emperor refused: "Let us rely on God. He will know how to order things better than us mortals."[45] The statesmen who accompanied Alexander – Pyotr Volkonsky, Hans Karl von Diebitsch and Alexander Chernyshyov – were not aware of the manifest.[46]

Alexander and Elizabeth traveled to the south separately; he reached Taganrog September 25 [O.S. September 13], she ten days later.[47] Their relations had considerably improved since the death of Alexander's illegitimate daughter Sophie Naryshkina in June 1824.[48] The reunion in Taganrog, according to Volkonsky, became the couple's second honeymoon[47] (Wortman noted that this and similar sentimental opinions, influenced by Nicholas's propaganda, should not be taken literally[49]).

After a stay with Elizabeth, Alexander left Taganrog on a tour of Crimea that was cut short by a bout of "bilious remittent fever"[50] that struck Alexander on November 9 [O.S. October 27] in Alupka.[51][52] Return to Taganrog brought no improvement; on November 10 Alexander lost consciousness for the first time.[53] He "strenuously refused all medical assistance" of his Scottish physician James Wylie.[54] Diebitsch reported the state of Alexander's health to Constantine in Warsaw.[55] The disease consumed Alexander and on November 29 [O.S. November 17] it seemed that he was in terminal agony. Only then did Diebitsch and Volkonsky notify the court in Saint Petersburg of the inevitable.

Alexander struggled for two more days and died at 10:50 on December 1 [O.S. November 19].[56] At the moment of Alexander's demise, Constantine and Michael stayed in Warsaw,[57] Nicholas and Empress Maria in Saint Petersburg.[58] Of the three men entrusted with full knowledge of Alexander's manifest, only Golitsyn was present in Saint Petersburg.[59]

Diebitsch promptly dispatched a courier to His Majesty Emperor Constantine in Warsaw; a second courier left for Saint Petersburg with a letter for Empress Maria.[60] The courier to Warsaw, owing to shorter distance and better roads, arrived at Constantine's palace two days ahead of the courier sent to Saint Petersburg. Constantine and Michael received the news in the evening[61] of December 7 [O.S. November 25].[57] Constantine immediately assembled his court and publicly renounced any claims to the throne. He spent all night drafting the responses to Diebitsch and to His Majesty Emperor Nicholas and Empress Maria in Saint Petersburg. The messenger, Grand Duke Michael, left Warsaw after dinner on December 8 [O.S. November 26].[62]

Interregnum in Saint Petersburg

Miloradovich

In the evening of December 7 [O.S. November 25] Governor-General of Saint Petersburg Mikhail Miloradovich brought the news of Alexander's terminal illness to Nicholas. News of Alexander's death arrived in Saint Petersburg on December 9 [O.S. November 27]. After a brief meeting with his mother Nicholas publicly pledged his oath to Emperor Constantine. The public took it for granted, Maria was startled: "Nicholas, what have you done? Didn't you know that you are heir presumptive?"[63] The oath sparked an unprecedented dynastic crisis: two principal contenders forfeited their rights in favor of each other in "a hitherto unheard-of struggle — a struggle not for the acquisition of power, but for its renunciation!".[64] The throne remained vacant.

Nicholas took the secret of his decision to his grave. According to Korff, Nicholas did not know the provisions of the 1823 manifest and merely executed his legal and moral obligations.[65] According to Sergey Trubetskoy, Nicholas was well aware of his rights but Miloradovich and general Alexander Voinov compelled him to step back. They met with Nicholas late in the evening of December 7. Miloradovich argued that Nicholas can not reign unless Constantine abdicates in public as a reigning Emperor. Independent action by Nicholas, said Miloradovich, will provoke a civil war because the troops will stand for Constantine. Nicholas reluctantly submitted to the military opposition. Schilder,[66] Hugh Seton-Watson,[67] Gordin,[66] Andreeva[68] accepted Trubetskoy's account as genuine. Safonov dismissed it as disinformation planted by Nicholas to justify his moment of weakness.[69]

Miloradovich temporarily assumed dictatorial power. From this moment and until the outbreak of the Decembrist revolt Miloradovich maintained a confident demeanor and persuaded Nicholas that "the city is quiet and tranquil" despite mounting evidence to the contrary.[70] Immediately after Nicholas's oath to Constantine Miloradovich instructed military commanders to administer the oath in their units.[71] Miloradovich broke the law twice: by initiating the oath without Constantine's own accession manifest,[72] and by initiating the oath in the troops before the civil government was sworn in.[73]

Miloradovich also took care of the original Manifest. His messenger arrived in Moscow on December 11 [O.S. November 29], and informed governor Dmitry Golitsyn that Constantine was now Emperor, that the city administration must be sworn immediately and that "a certain packet which has been deposited in 1823 in the Cathedral" must remain sealed.[74] Filaret objected but was compelled to accept the facts. Moscow was sworn to Constantine December 12 [O.S. November 30],[75] the 1st Army in Mogilev on December 13 [O.S. December 1].[76]

State council

Alexander Golitsyn rushed to Nicholas as soon as learned of the fait accompli. Their December 9 [O.S. November 27] meeting revealed the depth of the legal crisis that Nicholas had just made worse. Nicholas refused to act contrary to his oath to Constantine; both parties "separated with evident coolness".[77] At 2 p.m. Golitsyn opened the extraordinary session of the State Council.[78] He explained that a copy of Alexander's manifest, written by his own hand, was waiting for the occasion right there, in State Council files, and "bitterly deprecated the unnecessary precipitation in taking the oath". Minister of Justice Lobanov-Rostovsky and admiral Shishkov opposed, insisting on the legality of oath to Constantine, but the majority temporarily leaned towards Golitsyn's stance.[79]

Miloradovich, again, interfered in favor of Constantine. According to Trubetskoy, who attended at the Council meeting, the Manifest was presented as Alexander's will, rather than a law. Miloradovich argued that the Emperor may not appoint a successor through a will that contradicts pre-existing laws of succession; the Council can examine the will but may not act upon it.[80][81] According to Korff, the Council opened the secret envelope and read the manifest, but Miloradovich barred further talks with an argument that the manifest was already void: "Nicholas has solemnly renounced the right conferred upon him by the said Manifest."[79]

Council members suddenly found themselves in an inconvenient position of "a state authority rather than His Majesty's chancery".[82] Instead of acting on their own they herded into Nicholas' waiting room. Nicholas once again repeated his refusal of the throne and personally administered the council members' oath to Constantine.[83] By the end of the day the case appeared to be closed and couriers rushed the news of Constantine's accession to all corners of the empire.[82]

Indecision

On December 15 [O.S. December 3] Grand Duke Michael brought Constantine's letters to Saint Petersburg. Michael and Empress Maria persuaded Nicholas in the grave error he had made. Nicholas, now confident in his right to take the throne, realised that simply declaring himself emperor would, most likely, cause an insurrection. The only choice left, it seemed, was to invite Constantine to Saint Petersburg and have him formally abdicate in public.[84] On the same day a courier rushed the invitation to Warsaw.[85] On December 18 [O.S. December 6], Nicholas received a brief letter from Constantine, who firmly refused to travel to the capital, thus denying Nicholas any help in the succession crisis. "If everything is not arranged in accordance with our late Emperor's will", warned Constantine, "I shall remove into a still more distant retirement."[86]

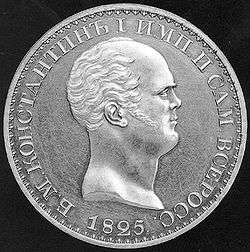

Government officials of all ranks expected the new tsar just as eagerly. On December 18 [O.S. December 6], Minister of Finance Georg von Cancrin ordered minting of a new coin bearing the profile of Emperor and Autocrat Constantine. Cancrin attended the December 9 [O.S. November 27] meeting of the State Council and was fully aware of the unfolding controversy, yet acted in confidence that Constantine was the emperor.[87] This confidence persisted despite the suspicious silence of Grand Duke Michael and his retinue. Michael did not pledge allegiance to Constantine and evaded all inquiries about His Majesty. Rumours and speculations made Michael's presence in the palace intolerable and the family council dominated by Empress Maria decided that he must return to Warsaw and personally persuade Constantine to come to Saint Petersburg.[88]

Maria gave Michael a mandate to intercept and read all letters that Constantine could send to her.[89] Michael met with Constantine's courier at Nennal[90] on December 20 [O.S. December 8]. He understood that his mission could not change Constantine's will and decided that he might be more useful to the House in Saint Petersburg rather than Warsaw.[91] He was not mistaken; his arrival in Saint Petersburg on the day of Decembrist revolt became a vital factor in persuading the troops in favor of Nicholas.[76]

Last warnings

At 6 a.m. Saturday, December 24 [O.S. December 12], Colonel Frederics brought Nicholas the "most urgent" report of the mounting conspiracy. The report, authored by Diebitsch and handwritten by Chernyshyov, was addressed to His Majesty Emperor Constantine – one copy to Saint Petersburg, another one to Warsaw. Hesitating, Nicholas opened the package and "was overwhelmed with unspeakable horror" of the conspiracy among his own Guards.[92] Diebitsch was confident in containing mutiny in his troops but, as for the rebels in Saint Peterburg and Moscow, he could only provide names.

Nicholas, still hoping to "conceal the whole affair in the closest secrecy" particularly from his mother, summoned Miloradovich and Alexander Golitsyn – the men who already earned his displeasure but whose offices were vital in maintaining order.[93] A quick search for the people named by Diebitsch brought no result: all were away on furlough,[94] said Miloradovich, and again assured Nicholas that "the city is tranquil". In fact, one person named in the report, cornet Svistunov, was present in Saint Peterburg and actively coordinated the rebels.

At 9 p.m. of the same day Nicholas received a cryptic and threatening message from Yakov Rostovtsev.[95] Rostovtsev's report did not specify any names but threatened Nicholas with a multitude of disasters. Surprisingly well informed about the correspondence between Saint Petersburg and Warsaw, Rostovtsev advised Nicholas to go to Warsaw himself rather than wait for Constantine.[96] His report, "a candle to the Lord and to Satan",[97] sounded like an ultimatum: "You have seriously irritated a great number against you. In the name of your own glory I entreat you not to hasten to reign."[98] Nicholas did not heed Rostovtsev's proposals which ran completely contrary to his plans. In another irrational twist, he treated Rostovtsev with respect and affection, and shielded him from prosecution.[95]

Accession of Nicholas

Decision

In the afternoon of December 24 [O.S. December 12] Nicholas received a letter from Constantine. Once again, Constantine refused to come to Saint Peterburg and blessed Nicholas onto the throne. The letter "terminated all indecision"[99] and started the countdown of "a virtual coup d'etat".[100] Nicholas sent a courier for Michael and summoned Nikolay Karamzin to prepare the draft of his accession manifest.[101] He then summoned three key officials representing the Church, the Guards and the civil government, and ordered them to convene a State Council meeting at 8 p.m. of the next day. The timing, thought Nicholas, allowed just enough time to bring in Michael, the living proof of his good faith.[102] The rest of the government, and most importantly the troops, were to be sworn on the following morning.[103] Nicholas wrote: "On the 14th I will be Emperor or dead."[104]

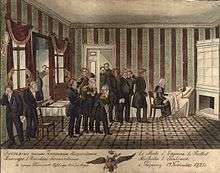

Twenty-three members of the State Council arrived in due time but Nicholas delayed the announcement for hours, waiting for Michael. Soon after midnight, in the very beginning of December 26 [O.S. December 14], Nicholas realized that no more delays were possible, and walked into the Council hall alone. He "seated himself in the place of the President" and read his accession manifest. This, according to Korff, was the first ever precedent when the State Council convened at night.[105] Nicholas went at lengths in explaining how the legal uncertainty set by Alexander lured him into pledging allegiance to Constantine. He specifically required "that the time of Our accession to the Throne be counted from the 19th day of November 1825", the day of Alexander's death, sealing the fact that Constantine had never reigned and that the oath to Constantine was merely a misunderstanding rectified by Nicholas.[106][107] The State Council accepted the fact without further discussion and was dismissed at about 1 a.m.[108]

Revolt

December 26 [O.S. December 14], "the longest day" of Nicholas I, coincided with the winter solstice: the sun rose at 9:04 and set at 2:58.[109] Nicholas assembled military commanders before sunrise. He again explained the background and motives for his decision. There were no objections, and the officers left to administer the oath to Nicholas in their units.[110]

Miloradovich did not attend this meeting. He arrived at the palace later and again assured Nicholas of "calm and tranquility", dismissing available intelligence. His police spectacularly failed in "a concurrence of other strange blunders, which it is difficult to explain at present".[111] Nicholas made a blunder of his own, by not printing and distributing copies of the Manifest and thus contributing to the rising agitation among civilians.[112] Decembrists were disorganized: their "dictator" Sergey Trubetskoy did not show up at all,[113] "the bravest men among the leaders developed an apathy and unwonted lack of nerve."[114] Like the tsar, they did not attempt to recruit civilian masses.[115]

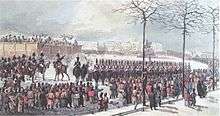

Oath in the troops proceeded smoothly until the men of Horse Artillery Regiment demanded personal assurance from Grand Duke Michael. Michael had just arrived in Saint Petersburg and Nicholas immediately sent him to speak to the troops.[116] At about noon Nicholas learned of the greater threat, the insurrection of the Moscow Regiment. Shouting "Hurrah for Constantine", the rebels took a stand in formation on the Senate Square, encouraged by the masses of civilians.[117] By noon the rebel forces on the square counted three thousand men, against already present nine thousand loyalists. Nicholas was there, "pale, weary, and eager to settle the whole affair as soon as possible."[115]

At around 12:30 Miloradovich tried to speak to the rebel troops and was fatally shot by Pyotr Kakhovsky and stabbed by Yevgeny Obolensky. Wilhelm Küchelbecker attempted shooting Grand Duke Michael. Another negotiator, Metropolitan Serafim, was forced away from the square.[118] Nicholas, still hoping to avoid bloodshed,[119] ordered an intimidating cavalry charge against the rebels. It miserably failed as horses lost balance and fell on icy pavement.[120] As time passed by, civilians flooded the square, forming a dense circle around the loyalists troops. Nicholas feared that the mob may overwhelm his troops after sunset. Worse, he saw his own soldiers defecting to the rebels.[121]

Generals pressed Nicholas for action, Karl Wilhelm von Toll reproached him: "Let me clear the square with gunfire or abdicate!".[122] At around 4 p.m. Nicholas ordered artillery fire against the rebels who did not dare to attack the batteries or otherwise change the outcome in their favour.[123] Canister shots killed more civilians than rebel soldiers.[124] Their flight from the square was checked by loyalist battalions blocking escape routes. Tsarist propaganda reported 80 dead,[125] later studies counted at least 1,271 dead, 903 of them civilians of low birth.[3]

Aftermath

The Southern Society attempted their own revolt: one thousand men of the Chernigov Regiment led by Sergey Muravyov-Apostol and Mikhail Bestuzhev-Ryumin ravaged Ukrainian towns and evaded government troops until a defeat at Kovalivka on January 15 [O.S. January 3], 1826. Hugh Seton-Watson wrote that it was "the first and the last political revolt by army officers"; Nicholas and his successors eradicated liberalism in the troops and secured their unconditional loyalty.[126] Immediately after suppressing the revolt in Saint Petersburg Nicholas took control of the investigation. Of six hundred suspects[127] 121 were put on trial. Five leaders were hanged, others exiled to Siberia;[128] Nicholas commuted most sentences in a demonstration of good will, sending the least offenders to fight as soldiers in the Caucasian War. Soldiers of the mutinous regiments were run through the gauntlet. Some died, others ended up fighting in the Caucasus or exiled in Siberia.[129] According to Anatole Mazour, the sentence was unusually harsh and revengeful;[130] according to Seton-Watson, it was in line with European practice of the time, but nevertheless contributed to public perception of Nicholas as "a dark and sinister figure" and of the Decembrists as selfless martyrs.[131]

"Challenge to Nicholas rule created an atmosphere of hostility, bitterness and fear ... it remained imprinted in Nicholas's mind as a traumatic moment that justified intensified surveillance and police persecution."[132] Contrary to Alexander's public image of a liberal conqueror, Nicholas chose to present himself as the defender of order, a distinctively Russian nationalist leader protecting the nation from foreign evils.[100] Lack of public support encouraged Nicholas to stage grand ceremonial events; the whole reign was marked by sentimental "demonstrations of attachments and love" to the tsar "who had evoked only antipathy".[49] He celebrated the day of his victory over the revolt with for the rest of his life, but the facts and analysis of 1825 events remained censored, contributing to the "Decembrist myth".[133]

Nicholas studied the grievances exposed in the 1826 investigation and incorporated them in his own reform program.[134] Despite his good intentions, his administration evolved into an overcentralized, oversized and incompetent system. Instead of managing the country for Nicholas, the system "loaded him with an innumerable magnitude of trivial affairs".[135] It was infested with laziness, indifference and corruption on all levels, although Seton-Watson wrote that the degree of bureaucratic vice has been exaggerated by contemporary critics.[136]

Constantine remained Viceroy of Poland until the November uprising and died in 1831 of cholera. He was "the only person treated by Nicholas as his equal and associate rather than a servant."[137] Nicholas and Michael remained close until Michael's death of a stroke in 1849, although Michael's militarism and tyranny over subordinates regularly annoyed Nicholas.[138]

Historiography

.jpg)

In 1847 Nicholas commissioned historian Modest von Korff to write the first history of the interregnum and the Decembrist revolt. Korff received limited but then unprecedented access to private records of the Romanovs and personally interviewed surviving high-ranking witnesses. The first edition, approved by Nicholas, was published in 1848 in mere twenty-five copies. The third, and the first public edition, was published in 1857 simultaneously in Russian, English, French and German languages. Korff's account, despite constraints of censorship, remains the mainstream version of the interregnum, but not the revolt. It was accepted in Imperial Russian (Schilder) and Soviet historiography (Militsa Nechkina) and in Western academia (Anatole Mazour, Vladimir Nabokov, Hugh Seton-Watson).

Memoirs of the Decembrists contradicted official history and each other. Sergey Trubetskoy, referring to the first report of Alexander's terminal illness received in Saint Petersburg December 7 [O.S. November 25], wrote that "the thought of the successor frightened everybody because the successor was unknown."[139] Andrey Rosen (1799–1884) wrote on the subject of Nicholas's oath to Constantine that "Count Miloradowitsch (sic) and Prince A. N. Galitzine, who knew the tenor of Alexander's will, exerted themselves in vain to prevent so doing, but Nicholas would not hear of any objection ... it was nevertheless everywhere known that Constantine has abdicated and that a will of Alexander's was in existence transferring the government to Nicholas... The members of the Senate knew that, since 1823, a will of Alexander's lay among their archives."[140] Rosen also speculated that because Nicholas "knew all along of the existence of secret societies" he voluntarily stepped aside "to avoid in this way any occasion of disturbance and discontent."[141]

Soviet historians concentrated on studies of the Decembrist movement and treated the interregnum as an insignificant episode in the grand picture of class struggle.[69] Interregnum resurfaced as an independent research topic in the 1970s. Historians, biographers and fiction authors sought alternative explanations of irrational events and named Alexander, Nicholas, Miloradovich and Empress Maria, alone or in various combinations, as the secret driving forces of the interregnum. None of these alternatives received wide support in academia.

- According to historian Mikhail Safonov, the interregnum was orchestrated by Empress Maria in alliance with Miloradovich. Maria allegedly sought power for herself and used Miloradovich to extract oath to Constantine from Nicholas. As soon as abdication of both Constantine and Nicholas became attested in public, the Crown of Russia would have passed to seven-year-old Alexander. Maria thus received a solid opportunity to rule the Empire as the regent for a whole decade. Nicholas realized the threat and launched his own coup d'état.[69]

- According to Kalinin's 1988 study of the Constantine ruble, Maria and Nicholas acted in accord. They feared that accession of Nicholas in accordance with Alexander's manifest will be opposed as a breach of Pauline laws and needed Constantine's formal abdication as a reigning monarch. Nicholas (not Miloradovich) initiated oath to Constantine with a simple goal of adding more weight to Constantine's decision.[142]

- According to Yakov Gordin (a poet born in 1935 who switched into history writing in the 1970s[143]) the interregnum was orchestrated by Miloradovich who acted as an independent dictator. He knew that Constantine, his wartime friend since the Swiss campaign of 1800, has no intention to rule. According to Gordin, Miloradovich hoped that the accession of Constantine would elevate him to the top of imperial hierarchy. With this in mind, he mobilized the generals' opposition against Nicholas and tolerated the Decembrist conspiracy.[144]

- German writer Vladimir Bryukhanov, in a radical development of Gordin's theory, wrote that Miloradovich was the puppetmaster of the Decembrists and led an influential military party including Arakcheev, Diebitsch, Pavel Kiselyov and even doctor Wylie. According to Bryukhanov's conspiracy theory, Miloradovich planned to take over absolute power from the House of Romanov.

- Tatyana Andreeva supported a toned-down version of Gordin's theory. According to Andreeva, Miloradovich assumed dictatorial authority but had no intention to become the "maker of the kings". Rather, he merely attempted to maintain the lawful order of succession and prevent social unrest.[145]

References

- 1 2 Schilder 1898, vol. 4 p. 388: "No one new about the existence of the Act proclaiming Nicholas the Heir, apart from three statesmen: count Arakcheyev, prince A. I. Golitsyn and archbishop of Moscow Filaret." (Russian: О существовании акта, назначавшего великого князя Николая Павловича наследником престола, при жизни Александра никто не знал, за исключением трех государственных сановников: графа Аракчеева, князя А. И. Голицына и архиепископа Московского Филарета.). Modern historians contest this opinion, arguing that either Empress Maria or Miloradovich or both of them were fully aware of the Manifest.

- ↑ Chapman, pp. 46-47.

- 1 2 Nechkina, p. 117, analyzed different numbers from different sources. Nicholas released an estimate of 80 dead. The most credible report, according to Nechkina, was authored by S. N. Korsakov of Saint Petersburg police and counted 1,271 dead of whom 903 were civilians of low classes (Russian: чернь, "the mob").

- ↑ Schilder 1901, p. 91.

- ↑ Korff, pp.31-32.

- ↑ Korff, p. 32; Seton-Watson, p. 194.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 24-26 and Schilder 1901, p. 91.

- ↑ Korff, p. 33.

- ↑ Korff, p. 36.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 38-39, provides English translation.

- ↑ Korff, p. 40.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 42-43. The full text, in English, is provided in Korff, pp. 45-49.

- 1 2 Korff, p. 43.

- ↑ Korff, p. 44.

- 1 2 Korff, p. 53.

- 1 2 Korff, p. 49.

- ↑ Korff, p. 51.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 51-52.

- ↑ Alexander wrote of her as his principal advisor, if not the deciding voice, on succession problem - Korff, p. 40.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 41, 63, 65-66; Riasanovsky, p. 31.

- ↑ Mazour, pp. 158-159.

- ↑ Riasanovsky, p. 31.

- ↑ Mazour, pp. 12-15, analyzed the effects of the Continental System on agriculture and industry.

- ↑ Mazour, pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Mazour, pp. 3-6, analyzed Alexander's motives for the 1808 ban.

- ↑ Wortman, p. 128.

- ↑ Kagan, pp. 11, 34.

- ↑ Kagan, p. 34.

- ↑ Mazur, pp. 41-45.

- ↑ Kagan, p. 33.

- ↑ Mazour, p. 66.

- ↑ Mazour, p. 68.

- ↑ Mazour, p. 71.

- ↑ Mazour, pp. 74-79.

- ↑ Mazour, pp. 84-85.

- ↑ Mazour, p. 99.

- ↑ Mazour, p. 109.

- ↑ Mazour, p. 103.

- ↑ Mazour, pp. 114-115.

- ↑ Mazour, pp. 154-155; Seton-Watson, pp. 193-194.

- ↑ Pipes, p. 290.

- ↑ Mazour, p. 155.

- ↑ Korff, p. 60. Troyat, p. 285, dates departure "on the night of September 1" (old style).

- ↑ Lee, p. 50. On pp. 50-51 Lee explains how Taganrog transformed from "a town as dirty and neglected as any town in Russia" to a town worthy of hosting the Tsar's residence.

- ↑ Troyat, p. 285.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 62-63; Schilder 1898, vol. 4 p. 388.

- 1 2 Troyat, p. 286.

- ↑ Troyat, p. 277.

- 1 2 Wortman, p. 130.

- ↑ Lee, p. 45, retells the report by Alexander's physician James Wylie.

- ↑ Lee, pp. 42-43. Schilder 1898, vol. 4 p. 370, also dated the onset of Alexander's terminal illness November 9 [O.S. October 27] and noted that at this date it was a mere cold. Troyat, p. 289, dated the onset November 16 [O.S. November 4] (when Alexander stayed in Mariupol) but, according to Lee, this was not the first bout but, rather, the gravest one.

- ↑ Ivan de Witt and Alexander Boshnyak, the informers who kept Alexander updated on the unfolding Decembrist conspiracy in the South, were also incapacitated by a similar disease. Conspiracy theorist Vladimir Bryukhanov suggested that all three men were slowly poisoned, contrary to the fact that such fevers were quite common in the marshlands around the Sea of Azov (Lee, pp. 42-43).

- ↑ Troyat, p. 290. Schilder 1898, vol. 4 pp. 563-567, provides full text of Pyotr Volkonsky's daily records of Alexander's illness starting from his return to Taganrog.

- ↑ Lee, pp. 41, 46-47. Some English sources render Wylie's name in reverse transliteration from Russian as Yakov Vassilievich Villiye, viz. Doctor To The Tsars by Ian Gray.

- ↑ Schilder 1898, vol. 4 p. 397. Vasilich, p. 23, noted that Constantine maintained absolute secrecy regarding Alexander's illness. Even their brother Michael was kept out of the loop until the news of Alexander's death reached Warsaw on November 25.

- ↑ Time of death: Schilder 1898, vol. 4 p. 384.

- 1 2 Korff, p. 61.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 66-72, provides full English translation of these two letters.

- ↑ Filaret was in Moscow; Arakcheyev, depressed by the recent murder of his mistress Nastasya Minkina, stayed in Novgorod.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 63-64.

- ↑ Korff, p. 64 and Schilder 1898, vol. 4 p. 398: 7 p.m.

- ↑ Korff, p. 66.

- ↑ Korff, p. 84.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 86-87.

- ↑ Korff, p. 82.

- 1 2 Gordin, p. 26.

- ↑ Seton-Watson, p. 194.

- ↑ Andreeva, p. 234.

- 1 2 3 Safonov 2001.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 111-112.

- ↑ Trubetskoy, p. 28, wrote that he was startled (Russian: я был крайне удивлён) to see Miloradovich issuing orders and dispatching messengers before the State Council meeting.

- ↑ Schilder 1901, p. 94.

- ↑ Wortman, p. 129; Andreeva, pp. 236-237.

- ↑ Korff, p. 102.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 103-108.

- 1 2 Korff, p. 130.

- ↑ Korff, p. 86.

- ↑ Korff, p. 87.

- 1 2 Korff, p. 89.

- ↑ Trubetskoy, p. 30.

- ↑ Riasanovsky, p. 32, noted that "Alexander's manifesto had precisely the form of a sovereign's personal will and testament in dynastic matters which Paul's law of succession had tried to abolish."

- 1 2 Korff, p. 90.

- ↑ Korff, p. 94.

- ↑ Korff, p. 117.

- ↑ Korff, p. 118.

- ↑ Korff, p. 126.

- ↑ Bartoshevich, p. 2.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 121-122, Bartoshevich, p. 1.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 122-123.

- ↑ Present-day Ninasi, Lohusuu Parish, Estonia

- ↑ Korff, p. 125.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 130-131.

- ↑ Korff, p. 136. Golitsyn, as Minister of Communications, controlled the postal system and the black room that intercepted suspicious letters.

- ↑ Korff, p. 137.

- 1 2 Rostovtsev, a Guards lieutenant recently inducted into the Northern Society, suffered from extreme stuttering and presented his report in writing. Rostovtsev stuttered for his whole life, yet reached a full general's rank. In 1849 Nicholas appointed Rostovtsev to investigate the case of the Petrashevsky Circle. Rostovtsev personally interrogated young Fyodor Dostoyevsky and supervised his mock execution. - Payne, p. 91.

- ↑ Korff, p. 149.

- ↑ Mazour, p. 163.

- ↑ Korff, p. 148.

- ↑ Korff, p. 139.

- 1 2 Wortman, p. 129.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 142, 155. Karamzin declined the honour and the manifest was authored by Mikhail Speransky.

- ↑ Michael was at Nennal, 26 versts or 280 kilometers from Saint Petersburg. The round trip to Nennal and back, with all resources of the Empire, could not be made in 24 hours.

- ↑ Korff, p. 143.

- ↑ Korff, p. 154.

- ↑ Korff, p. 164.

- ↑ Korff, p. 162.

- ↑ Rosen, p. 4: "This period of time was obliterated by a manifesto of the Emperor Nicholas accession to be kept on 19 November 1825..."

- ↑ Korff, p. 168.

- ↑ Bagby, p. 154.

- ↑ Korf, p. 173.

- ↑ Korff, p. 175.

- ↑ Korff, pp. 175-176, 181.

- ↑ Mazour, pp. 171-175, analyzed Trubetskoy's motives. Trubetskoy's own memoirs omit the revolt altogether.

- ↑ Nabokov, p. 346.

- 1 2 Mazour, p. 176.

- ↑ Korff, p. 179.

- ↑ Korff, p. 181, noted that the mob was openly supporting Constantine: he remained their legitimate tsar, and Nicholas did nothing to present his case to the masses.

- ↑ Mazour, p. 177.

- ↑ Mazour, p. 178; Seton-Watson, p. 195.

- ↑ Mazour, pp. 177-178.

- ↑ Mazour, p. 178; Nechkina, p. 115.

- ↑ Mazour, p. 78

- ↑ Mazour, p. 178.

- ↑ Nechkina, p. 116.

- ↑ This was the official body count declared by Nicholas. According to memoirs of baron Kaulbars, reproduced in Vasilich, vol. 2 p. 93, rumour of the day set the number of dead at "70-80". Kaulbars wrote that he had counted 56 dead rebels and five civilians - these bodies were collected from Senate Square and piled near St. Isaac's fence. Apart from these dead, Kaulbars mentioned one killed loyalist of his regiment and "a few" killed in other areas of the city. He did not mention the bodies dumped in the Neva River.

- ↑ Seton-Watson, pp. 196-197.

- ↑ The total of six hundreds contains the Decembrists along with innocent people, uninvolved family members and fictitious names invented by the suspects. It does not include enlisted men of the mutinous regiments.

- ↑ Seton-Watson, p. 197.

- ↑ Nechkina, pp. 134-135; Mazour, p. 221.

- ↑ Mazour, pp. 214, 217.

- ↑ Seton-Watson, p. 200.

- ↑ Wortman, p. 128. See also Mazour, pp. 265-266: "he always considered developments from a viewpoint determined by his sad memories of December 14."

- ↑ Mazour, p. 271; Wortman, p. 129.

- ↑ Seton-Watson, p. 202. Mazour, pp. 267-268, wrote that Nicholas referred to the report on Decembrist ideas for all his life. Alexander Borovkov, secretary of the 1826 investigation, deliberately biased the report in favor of the Decembrists' most constructive proposals, effectively plagiarizing the Decembrist program.

- ↑ Seton-Watson, p. 210, cites memoirs of Modest von Korff.

- ↑ Seton-Watson, p. 211.

- ↑ Riasanovsky, p. 38.

- ↑ Riasanovsky, pp. 38-39.

- ↑ Trubetskoy, p. 26.

- ↑ Rosen, pp. 2-3.

- ↑ Rosen, p. 3.

- ↑ Melnikova, p. 11.

- ↑ Polukhina, p. 41.

- ↑ Gordin, p. 60.

- ↑ Andreeva, p. 235.

Sources

- Andreeva, T. V. (1998, in Russian). Imperator Nikolai Pavlovich i graf M. A. Miloradovich (Император Николай Павлович и граф М. А. Милорадович). СПБ: Философский век, выпуск 6 (The Philosophical Age. Almanac 6. Russia at the Time of Nicholas I: Science, Politics, Enlightenment. Ed. by T. Khartanovich, M. Mikeshin. St. Petersburg, 1998. 304 p.).

- Bagby, Lewis (1990). Alexander Bestuzhev-Marlinsky. Penn State Press. ISBN 0-271-02613-8, ISBN 978-0-271-02613-8.

- Bartoshevich, V. V. (1991, in Russian). Zametki o konstantinovskom ruble (Заметки о константиновском рубле), in: Melnikova, A. S. et al. (1991, in Russian). Konstantinovsky rubl. Novye materialy i opisaniya (Константиновский рубль. Новые материалы и исследования). Moscow: Finansy i statistika. ISBN 5-279-00490-1.

- Chapman, Tim (2001). Imperial Russia, 1801-1905. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23110-8, ISBN 978-0-415-23110-7.

- Gordin, Yakov (1989, in Russian). Myatezh reformatorov (Мятеж реформаторов). 3rd edition: Lenizdat. ISBN 5-289-00263-4.

- Kagan, Frederick (1999). The military reforms of Nicholas I: the origins of the modern Russian army. Pallgrave McMillan. ISBN 0-312-21928-8, ISBN 978-0-312-21928-4.

- Korff, M. A. (1857). The accession of Nicholas I. London: John Murray. (Russian 1857 edition)

- Lee, Robert (1854). The last days of Alexander, and the first days of Nicholas. London: Robert Bentley.

- Mazour, Anatole (1937). The first Russian revolution, 1825: the Decembrist movement, its origins, development, and significance. Stanford University Press. Reissue: ISBN 0-8047-0081-8, ISBN 978-0-8047-0081-8.

- Melnikova, A. S. (1991, in Russian). Konstantinovsky rubl i istoriya ego izuchenia (Константиновский рубль и история его изучения), in: Melnikova, A. S. et al. (1991, in Russian). Konstantinovsky rubl. Novye materialy i opisaniya (Константиновский рубль. Новые материалы и исследования). Moscow: Finansy i statistika. ISBN 5-279-00490-1.

- Nabokov, Vladimir (1990 reprint). Eugene Onegin: A Novel in Verse: Commentary. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01904-5, ISBN 978-0-691-01904-8.

- Nechkina, Militsa (1984, in Russian). Dekabristy (Декабристы). Moscow: Nauka.

- Payne, Robert (1961). Dostoyevsky: a human portrait. Knopf.

- Pipes, Richard (1975). Russia under the old regime. Scribner. ISBN 0-684-14041-1, ISBN 978-0-684-14041-4

- Polukhina, Valentina (2008). Brodsky through the eyes of his contemporaries, Volume 1. Academic Studies Press. ISBN 1-934843-15-6, ISBN 978-1-934843-15-4.

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas (1967). Nicholas I and official nationality in Russia, 1825-1855. University of California Press.

- Rosen, Andrey (1872). Russian conspirators in Siberia. London, Smith, Elder & Co.

- Safonov, M. M. (1994, in Russian). K istorii mezhdutsarstviya (К истории междуцарстия). Proceedings of the Mavrodinskie conference 10–12 December 1994, Saint Petersburg (Мавродинские чтения: материалы к докладам 10-12 октября 1994 г., Санкт-Петербург). Saint Petersburg University.

- Safonov, M. M. (2001, in Russian). 14 dekabrya 1825 goda kak kulminacia mezhdutsarstviya (14 декабря 1825 года как кульминация междуцарствия), in: 14 dekabrya 1825 goda. Istochniki. Issledovaniya. Istoriographia. Bibliographia. (14 декабря 1825 года. Источники. Исследования. Историография. Библиография.) vol. 4. (2001). Moscow: Nestor. ISBN 9975-9606-9-3.

- Schilder, Nikolay (1898, in Russian). Imperator Alexandr Pervy (Император Александр Первый). Vol. 4. Saint Petersburg: A. S. Suvorin.

- Schilder, Nikolay (1901, in Russian). Pyatdesyat let russkoy istorii: devyatnatsaty vek (Пятьдесят лет русской истории; Девятнадцатый век). Saint Petersburg: A. F. Marks.

- Seton-Watson, Hugh (1988). The Russian empire, 1801-1917. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822152-5, ISBN 978-0-19-822152-4.

- Troyat, Henri (2002 English edition). Alexander of Russia: Napoleon's Conqueror. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3949-3, ISBN 978-0-8021-3949-8. Original published in French in 1981.

- Trubetskoy, S. P. (1906, in Russian). Zapiski knyazya S. P. Trubetskogo (Записки князя С. П. Трубецкого). Saint Petersburg: Sirius.

- Vasilich, G. (1908, in Russian). Razruha 1825 goda (Разруха 1825 года; Восшествие на престол императора Николая I). Saint Petersburg: Sever.

- Wortman, Richard (2006). Scenarios of power: myth and ceremony in Russian monarchy from Peter the Great to the abdication of Nicholas II. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-12374-8, ISBN 978-0-691-12374-5.