Saint-Germain-des-Prés

| Saint-Germain-des-Prés | |

|---|---|

| Neighbourhood | |

|

| |

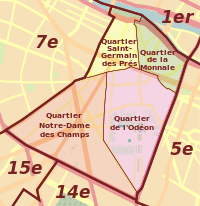

The four quarters of the 6th arrondissement | |

| Coordinates: 48°51′14″N 2°20′04″E / 48.85389°N 2.33444°ECoordinates: 48°51′14″N 2°20′04″E / 48.85389°N 2.33444°E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Île-de-France |

| City | Paris |

| Arrondissement | 6th |

| Population (1999) | |

| • Total | 5,154 |

Saint-Germain-des-Prés (French pronunciation: [sɛ̃ ʒɛʁmɛ̃ de pʁe]) is one of the four administrative quarters of the 6th arrondissement of Paris, France, located around the church of the former Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Its official borders are the River Seine on the north, the rue des Saints-Pères on the west, between the rue de Seine and rue Mazarine on the east, and the rue du Four on the south. Residents of the quarter are known as Germanopratins.[1]

The quarter has several famous cafés, including Les Deux Magots, Café de Flore, le Procope, and the Brasserie Lipp, and a large number of bookstores and publishing houses. In the 1940s and 1950s, it was the centre of the existentialist movement (associated with Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir). It is also home to the École des Beaux-Arts, the famed school of fine arts, and the Musée national Eugène Delacroix, in the former apartment and studio of painter Eugène Delacroix.

History

The Middle Ages

Until the 17th century the land where the quarter is located was prone to flooding from the Seine, and little building took place there; it was largely open fields, or Prés, which gave the quarter its name.

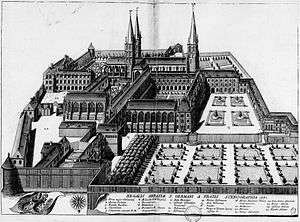

The Benedictine abbey in the center of the quarter was founded in the 6th century by the son of Clovis I, Childebert I (ruled 511–558). In 542, while making war in Spain, Childebert raised his siege of Zaragoza when he heard that the inhabitants had placed themselves under the protection of the martyr Saint Vincent. In gratitude the bishop of Zaragoza presented him with the saint's stole. When Childebert returned to Paris, he caused a church to be erected to house the relic, dedicated to the Holy Cross and Saint Vincent, placed where he could see it across the fields from the royal palace on the Île de la Cité. In 558, St. Vincent's church was completed and dedicated by Germain, Bishop of Paris on 23 December; on the same day, Childebert died. Close by the church a monastery was erected. The Abbey church became the burial place of the dynasty of Merovingian Kings. Its abbots had both spiritual and temporal jurisdiction over the residents of Saint-Germain (which they kept until the 17th century). Since the monastery had a rich treasury and was outside the city walls, it was plundered and set on fire by the Normans in the ninth century. It was rebuilt in 1014 and rededicated in 1163 by Pope Alexander III to Bishop Germain, who had been canonized.

The church and buildings of the Abbey were rebuilt in stone c. 1000 AD, and the Abbey developed into a major center of scholarship and learning. A village grew up around the Abbey, which had about six hundred inhabitants by the 12th century. The modern rue du Four is the site of the old ovens of the monastery, and the dining hall was located along the modern rue de l'Abbaye. A parish church, the church of Saint-Pierre, also was built on the left bank, at the site of the present Ukrainian catholic church; its parish covered most of the modern 6th and 7th arrondissements. The fortifications of King Philip Augustus (1358–1383), the first built around the entire city, left Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés just outside the walls.

The Saint-Germain Fair

Beginning in the Middle Ages, Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés was not only a religious and cultural center, but also an important marketplace, thanks to its annual fair, which attracted merchants and vendors from all over Europe. The Foire Saint-Germain was already famous in 1176, when it allocated half of its profits to the King. The fair opened fifteen days after Easter, and lasted for three weeks. The dates and the sites varied over the years; beginning in 1482 it opened in 1 October and lasted eight days; in other years it opened 11 November or 2 February. Beginning in 1486, it was held in a portion of the gardens of the Hôtel de Navarre, close to the modern rue Mabillon. There were three hundred forty stalls at the fair of 1483; Special buildings were erected for the fair in 1512, which contained 516 stalls. The fair was also famous for the gambling, debauchery, and the riots that ensued when groups of rowdy students from the nearby university invaded the fair. The buildings burned on the night of 17–18 March 1762, but were quickly rebuilt. The fair continued annually until the Revolution in 1789, when it was closed down permanently.[2]

The Renaissance

At the end of the 16th century, Margaret of Valois (1553–1615) the estranged wife of King Henry IV of France but still officially Queen of France, decided to build a residence in the quarter, in lands belonging to the Abbey near the Seine just west of the modern rue de Seine, near the present Institut de France. She built a palace with extensive gardens and established herself as a patroness of literature and the arts, until her death in 1615.

17th–18th centuries: theatre and the first cafés

In 1673 the most famous theatrical troupe in the city, the Comédie-Française, was expelled from its building on rue Saint‑Honoré and moved to left bank, to the passage de Pont-Neuf (the present-day rue Jacques‑Callot), just outside the Saint‑Germain quarter. Its presence displeased the authorities of the neighboring Collége des Quatres-Nations (the present Institut de France) and in 1689 they moved again, this time to the rue des Fossés des Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés (the modern rue de l'Ancienne‑Comédie), where they remained until 1770. The poor condition of the theater roof forced them to move in that year to the right bank, to the Hall of machines of the Tuileries Palace, which was much to large for them. In 1797 they moved back to the Left Bank, to the modern Odéon Theatre.[3]

The first café in Paris appeared in 1672 at the Saint-Germain Fair, served by an Armenian named Pascal. When the fair ended he opened a more permanent establishment on the quai de l'Ecole, where he served coffee for two sous and six deniers per cup. It was considered more of a form of medication than a beverage to be enjoyed, and it had a limited clientele. He left for London, and another Armenian named Maliban opened a new café on the rue de Buci, where he also sold tobacco and pipes. His café also had little commercial success, and he left for Holland. A waiter from his café, an Armenian named Grigoire, born in Persia, took over the business and opened it on rue Mazarine, near the new home of Comédie-Française. When the theater moved in 1689, he moved the café to the same location, on the rue des Fossés‑Saint‑Germain. The café was then taken over by a Sicilian, Francesco Procopio dei Coltelli, who had worked as a waiter for Pascal in 1672. he renamed the café Procope, and expanded its menu to include tea, chocolate, liqueurs, ice cream and configures. It became a success; the café is still in business.[4] By 1723 there were more than three hundred eighty cafés in the city. The Café Procope particularly attracted the literary community of Paris, because many book publishers, editors and printers lived in the quarter. The writers Diderot and d'Alembert are said to have planned their massive philosophical work, the Encyclopédie, at Procope, and at another popular literary meeting place, the Café Landelle on the rue de Buci.

The Treaty of Paris

A significant event in American history took place on 3 September 1783 at the Hotel York at 56 rue Jacob; the signing of the Treaty of Paris between Britain and the United States, which ended the American Revolution and granted the U.S. its independence. The signing followed the American victory at the Siege of Yorktown, won with assistance of the French fleet and French army. The American delegation included Benjamin Franklin, John Adams and John Jay. After the signing, they remained for a commemorative painting by the American artist Benjamin West, but the British delegates refused to pose for the painting, so the painting was never finished.

The French Revolution

Because of its numerous printers and publishers, Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés, and especially the Cordeliers Section of what is now the Sixth Arrondissement, became centers of revolutionary activity after 1789; they produced thousands of pamphlets, newspapers, and proclamations which influenced the Parisian population and that of France as a whole. The prison of the Abbey of Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés, a two-story building near the church, was filled with persons who had been arrested for suspicion of counter-revolutionary motives: former aristocrats, priests who refused to accept the revolutionary Constitution, foreigners, and so forth. By September 1792, Paris prisons were quite full. France, under the leadership of her Paris Convention, had declared herself a republic. The former king and queen were political prisoners and were moved from the Tuiliries Palace to the old Knights Templar towers on the right bank, where there was less risk of rescue or escape. France was at war; the Duke of Brunswick had just issued his menacing manifesto, stating that if the former monarchy were not restored, he would raze Paris, and his troops were only a few days away. Now these political prisoners began to be viewed as a genuine threat, should any of them be conspiring with France's enemies. In what was a planned but inhumane tactic, politicians at Paris sent bands of criminals, armed mainly with pikes and axes, into each prison. Although at least one deputy from the Convention accompanied each band, the results were horrifying. Hundreds of prisoners were cut down between the end of August and the first week in September. As Englishman Arthur Young noted, the street outside one prison literally ran red with blood. The former Cordeliers Convent, closed by the revolutionaries, became the headquarters of one of the most radical factions, whose leaders included Georges Danton and Camille Desmoulins, though both would be run out by ever more extreme factions. The radical revolutionary firebrand, Swiss physician Jean-Paul Marat, lived nearby in the Cordeliers Section; after months of struggle, Marat, Desmoulins, and their party managed to get their enemies in the Girondist group arrested, and Marat was stabbed to death in his medicinal bath by Girondist sympathizer Marie Charlotte Corday the following July (1793).

The Monastery of Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés was closed and its religious ornaments were taken away. The buildings of the monastery were declared national property and sold or rented to private owners. One large building was turned into a gunpowder storeroom; it exploded, wrecking a large part of the monastery.

Another large monastery in the quarter, that of the Petits-Augustins, had been closed and stripped of its religious ornamentation. The empty buildings were taken over by an archeologist, Alexandre Lenoir, who turned it into a depot to collect and preserve the furniture, decorations, and art treasures of the nationalised churches and monasteries. The old monastery officially became the Museum of French Monuments. The paintings collected were transferred to the Louvre, where they became the property of the Central Museum of the Arts, the ancestor of the modern Louvre, which opened there at the end of 1793.[5]

The 19th century

The École des Beaux-Arts

The École des Beaux Arts, the national school of architecture, painting and sculpture, was established after the Revolution at 14 rue Bonaparte, on the site of the former monastery of the Petits-Augustins. Its faculty and students included many of the most important artists and architects of the 19th century; the faculty included Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Gustave Moreau. The students included painters Pierre Bonnard, Georges Seurat, Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, and the American Thomas Eakins. Architects graduated from the school included Gabriel Davioud, Charles Garnier, and the Americans Julia Morgan, Richard Morris Hunt and Bernard Maybeck. The painter Eugène Delacroix established his residence and studio at 6 rue de Furstenberg and lived there from 1857 until his death in 1863.

Haussmann

The vast public works projects of Napoleon III and his Prefect of the Seine, Georges-Eugene Haussmann in the 1860s dramatically changed the map of the quarter. To reduce the congestion of the narrow maze of streets on the Left Bank, Haussmann had intended to turn the rue des Ecoles into a major boulevard, but the slope was too steep, and he decided instead to construct boulevard Saint‑Germain through the heart of the neighborhood. It was not completed until 1889. He also began a wide south to north axis from the Montparnasse railroad station to the Seine. which became the rue de Rennes. The rue de Rennes was only completed as far as the parvis in the front of the Church of Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés by the end of the Second Empire in 1871, and stopped there, sparing the maze of narrow streets between boulevard Saint‑Germain and the river.[6]

Oscar Wilde

The quarter was also the temporary home of many musicians, artists and writers from abroad, including Richard Wagner who lived for several months on rue Jacob.

The writer Oscar Wilde spent his last days in the quarter, at the small, run-down hotel called the Hotel d'Alsace at 13 rue des Beaux‑Arts, near the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. He wandered the streets along, and spent his money he had on alcohol.[7] He wrote to his editor, "This poverty really breaks one's heart: it is so sale, so utterly depressing, so hopeless. Pray do what you can." He corrected proofs of his earlier work, but refused to write anything new. "I can write, but have lost the joy of writing", he told his editor.[8] He kept enough sense of humor to remark: "My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One of us has got to go."[9] He died on 30 November 1900, and was first buried in a small cemetery outside the city, before being reburied in 1909 at Pere Lachaise.

The small hotel where Wilde died became famous; later guests included Marlon Brando and Jorge Luis Borges. It was completely redecorated by Jacques Garcia, and is now a five-star luxury hotel called L'Hotel.

The 20th century: non-conformism

in the first half of the 20th century, Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés and nearly the whole of the 6th arrondissement, was a densely populated working‑class neighborhood, whose population was declining. The population of the 6th arrondissement was 101,584 in 1921, and dropped to 83,963. In the postwar years, the housing was in poor condition; only 42 percent of residences had indoor toilets, and only 23 percent had their own showers or baths. By 1990 the population of the 6th fell to 47,942, a drop of fifty percent in seventy years. In 1954 workers represented 19.2 percent of the population of the quarter; 18.1 percent in 1962.[10]

In the years after World War II, Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés was known primarily for its cafés and its bars, its diversity and its non-conformism. The bars were a popular destination for American soldiers and sailors after the war. It was also known as a meeting place for the largely-clandestine gay community of Paris, which at the time frequented the Café de Flore and the Café Carrefour, an all-night restaurant.[11] Because of its low rents and proximity to the University, the quarter was also popular with students from the French colonies in Africa. There were between three and five thousand African students in the city; their association had its headquarters at 184 boulevard Saint‑Germain and 28 rue Serpente. Because of the number of workers, it also hosted an important bureau of the French Communist Party.

Jazz

.jpg)

Immediately after the War, Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés and the nearby Saint-Michel neighbourhood became home to many small jazz clubs, mostly located in cellars, due to the shortage of any suitable space, and because the music at late hours was less likely to disturb the neighbors. The first to open in 1945 was the Caveau des Lorientais, near boulevard Saint‑Michel, which introduced Parisians to New Orleans Jazz, played by clarinetist Claude Luter and his band. It closed shortly afterwards, but was soon followed by cellars in or near Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés; Le Vieux-Columbier, the Rose Rouge, the Club Saint-Germain; and the most famous, Le Tabou. The musical styles were be-bop and jazz, led by Sydney Bechet and trumpet player Boris Vian; Mezz Mezzrow, André Rewellotty, guitarist Henri Salvador, and singer Juliette Gréco. The clubs attracted students from the nearby university, the Paris intellectual community, and celebrities from the Paris cultural world. They soon had doormen who controlled who was important or famous enough to be allowed inside into the cramped, smoke-filled cellars. A few of the musicians went on to celebrated careers; Sidney Bechet was the star of the first jazz festival held at the Salle Pleyel in 1949, and headlined at the Olympia music hall in 1955. The musicians were soon divided between those who played traditional New Orleans jazz, and those who wanted more modern varieties. Most of the clubs closed by the early 1960s, as musical tastes shifted toward rock and roll.[12]

Existentialism

The literary life of Paris after World War II was centered in Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés, both because of the atmosphere of non-conformism and because of the large concentration of book stores and publishing houses. Because most writers lived in tiny rooms or apartments, they gathered in cafés, most famously the Café de Flore, the Brasserie Lipp and Les Deux Magots, where the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre and writer Simone de Beauvoir held court. Sartre (1905–1980) was the most prominent figure of the period; he was a philosopher, the founder of the school of existentialism, but also a novelist, playwright, and theater director. He also was very involved in the Paris politics of the left; after the war he was a follower (though not a member) of the Communist Party, then broke with the communists after the Soviet invasion of Hungary, and became an admirer of Fidel Castro and the Cuban Revolution, then of Mao-tse Tung. In 1968 he joined the demonstrations against the government, standing on a barrel to address striking workers at the Renault factory in Billancourt.[13] The legends of Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés describe him as frequenting the jazz clubs of the neighborhood, but Sartre wrote that he rarely visited them, finding them too crowded, uncomfortable and loud.[14] Simone de Beauvoir (1902–1986), the lifelong companion of Sartre, was another important literary figure, both as an early proponent of feminism and as an autobiographer and novelist.

After the Second World War, the neighbourhood became the centre of intellectuals and philosophers, actors and musicians. Existentialism co-existed with jazz in the cellars on the rue de Rennes. Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Juliette Gréco, Jean-Luc Godard, Boris Vian, and François Truffaut were all at home there. But there were also poets such as Jacques Prévert and artists such as Giovanni Giacometti. As a residential address in Saint‑Germain is no longer quite as fashionable as the area further south towards the Jardin du Luxembourg, partly due to Saint‑Germain's increased popularity among tourists.

Terrorism

On 29 November 1965, Mehdi Ben Barka, the leader of opposition to the government of the King of Morocco, was kidnapped as he emerged from the door of the Brasserie Lipp. his body was never found.[15]

Transportation

The area is served by the stations of the Paris Métro:

Literature

Many writers have written about this Parisian district in prose such as Boris Vian, Marcel Proust, Gabriel Matzneff (see La Nation française), Jean-Paul Caracalla or in Japanese poetry in the case of Nicolas Grenier. Egyptian writer Albert Cossery spent the later part of his life living in a hotel in this district. James Baldwin frequented the cafés, written about in Notes of a Native Son. Charles Dickens describes the fictional Tellson's Bank as "established in the Saint Germain Quarter of Paris" in his novel A Tale of Two Cities.

Economy

At one time numerous publishers were located in the area. By 2009 many publishers, including Hachette Livre and Flammarion had moved out of the community.[16]

See also

References

Notes and Citations

- ↑ Dussault 2014, p. 21.

- ↑ Fierro 1996, p. 876.

- ↑ Fierro 1996, pp. 791–792.

- ↑ Fierro 1996, p. 742.

- ↑ Sarmant 2012, p. 145.

- ↑ Fierro 1996, pp. 528–529.

- ↑ Ellmann 1988, p. 527.

- ↑ Ellmann 1988, p. 528.

- ↑ Ellmann 1988, p. 546.

- ↑ Dussault 2014, p. 22.

- ↑ Dussault 2014, pp. 59–63.

- ↑ Bezbakh 2004, p. 872.

- ↑ Bezbakh 2004, p. 864.

- ↑ Dussault 2014, p. 128.

- ↑ Fierro 1996, p. 649.

- ↑ Launet 2009.

Bibliography

- Dussault, Éric (2014). L'invention de Saint-Germain-des-Prés (in French). Paris: Vendémiere. ISBN 978-2-36358-078-8.

- Bezbakh, Pierre (2004). Petit Larousse de l'histoire de France (in French). Paris: Larousse. ISBN 978-2-03-505369-5.

- Ellmann, Richard (1988). Oscar Wilde. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-394-75984-5.

- Fierro, Alfred (1996). Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris. Bouquins (in French). Paris: Robert Laffont. ISBN 978-2-221-07862-4. LCCN 96206674. OL 610571M.

- Launet, Edouard (2 November 2009). "Pas de quartier pour les éditeurs". Libération (in French). Paris. ISSN 0335-1793. Archived from the original on 5 November 2009.

Après Flammarion ou Hachette, le Seuil va quitter le périmètre littéraire de Saint‑Germain‑des‑Prés, à Paris. Non sans nostalgie, et en y gardant un pied‑à‑terre de prestige

- Sarmant, Thierry (2012). Histoire de Paris : politique, urbanisme, civilisation. Gisserot Histoire (in French). Paris: Editions Gisserot. ISBN 978-2-7558-0330-3.

External links

- "The trendy and cultural guide of Saint-Germain-des-Prés". Les Germanopratines.