Sampul tapestry

The Sampul tapestry is an ancient woolen wall-hanging found at the Tarim Basin settlement of Shanpula (Chinese: 山普拉) also known as Sampul, in Lop County, Xinjiang, China,[1] close to ancient city of Khotan.[2] The object has many Hellenistic features, linking it to the Greek settlements of Central Asia, which existed from 180 BCE until the 1st century CE.

Description

The full tapestry is 48 cm wide and 230 cm long.[3] The centaur fragment is 45 cm by 55 cm, warrior's face fragment is 48 cm by 52 cm.[4] The recovered tapestry only constitutes the left decorative border of what would be a much bigger wall hanging.[4]

Made of wool,[5] it comprises 24 threads of various colours.

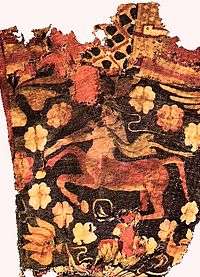

The tapestry depicts a man with Caucasoid features,[6] including blue eyes,[7] and a centaur.[8] If lost fabric is accounted for, the soldier would be about six times as tall as the centaur.[9] The subject is identified as a warrior by the spear he is holding in his hand as well as a dagger tucked on his waist.[10] He wears a tunic with rosette motifs. His headband could be a diadem, a symbol of kingship in the Hellenistic world – and represented on Macedonian and other Greek coins.

The centaur is playing a horn while wearing a cape and a hood.[11] Surrounding him is a diamond-shaped floral ornament.[4]

Due to heavy looting at the location, the dating of the material is uncertain. It has been assigned dates from the 3rd century BCE to the 4th century CE.[4][7][12][13][14]

Discovery

The tapestry was excavated in 1983–1984 at an ancient burial ground in Sampul (Shanpula), 30 km east of Hotan (Khotan), in the Tarim Basin.[15]

The tapestry was, curiously, fashioned into a pair of man's trousers (all the other trousers found in Sampul had no decoration).[16]

Origin

It is uncertain where the tapestry was made, although the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom in Central Asia has been suggested to be a possibility. The technique used for the tapestry, with more than 24 threads of different colours, is a typically western one. The centaur's cape and hood are a central Asian modification of the Greek motif.[17] The fact that he plays a horn also distinguishes him from the Greek prototypes.[4] Flower diamond motif on the warrior's lapel are of central Asian origin.[12] Certain motifs, particularly the animal head on the soldier's dagger, suggest that the tapestry originated in the kingdom of Parthia in northern Iran.[18]

Rome has also been proposed as a possible source.[18] Another suggestion is that it is locally made as Tang annal New Book of Tang mentioned that local people of Khotan were good at textile and tapestry work when Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141-87 BC) opened the Silk Road to Khotan during the first century BC. The tapestry may have been made roughly a century before the Han Chinese conquest of the Tarim Basin under Wudi.[19] Hellenistic tapestries have also been found in Loulan by Aurel Stein, indicating a cultural link between Loulan and Khotan.[19]

Significance

The existence of this tapestry tends to suggest that contacts between the Hellenistic kingdoms of Central Asia and the Tarim Basin, at the edge of the Chinese world occurred from around the 3rd century BCE.

Exhibition history

The tapestry is on permanent display in the Xinjiang Museum, Ürümqi, China.[14]

Centaur and head fragments of the tapestry have been a part of a major exhibition China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 AD, held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from 12 October 2004 to 23 January 2005.[20][21]

From 18 February to 5 June 2011, they were displayed at the Penn Museum, Philadelphia, in exhibition Secrets of the Silk Road.[22][23]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sampul tapestry. |

Notes

- ↑ Wood 2002, p. 37, p. 255

- ↑ Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012), "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)," in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, p. 15, ISSN 2157-9687.

- ↑ Hansen 2012, p. 285, fn. 6

- 1 2 3 4 5 Zhao 2004, p. 194

- ↑ Wood 2002, p. 37; Zhao 2004, p. 194

- ↑ Time Life 1993, p. 81; Wood 2002, p. 37; Hansen 2012, p. 202

- 1 2 Time Life 1993, p. 81

- ↑ Time Life 1993, p. 81; Wood 2002, p. 37; Hansen 2012, pl. 13 image + text, p. 202

- ↑ Zhao 2004, p.195

- ↑ Zhao 2004, p. 194; Hansen 2012, p. 202

- ↑ Hansen 2012, pl. 13 text; Zhao 2004, p. 194

- 1 2 Hansen 2012, pl. 13 text

- ↑ Image gallery for the Secrets of the Silk Road exhibition at the Penn Museum

- 1 2 Wood 2002, p. 255

- ↑ Wood 2002, p. 37, p. 255; Zhao 2004, p. 194; Hansen 2012, p. 201

- ↑ Hansen 2012, pl. 13 text, p. 202

- ↑ Zhao 2004, p. 194; Hansen 2012, pl. 13 text

- 1 2 Hansen 2012, p. 202

- 1 2 Lucas, Christopoulos (August 2012). "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers (230): 9–20. ISSN 2157-9687.

- ↑ Zhao 2004

- ↑ China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 AD at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ↑ Sheng 2010, p. 33, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Secrets of the Silk Road at the Penn Museum

References

- China's Buried Kingdoms. Time Life. 1993. ISBN 1-84447-050-4.

- Valerie Hansen (2012). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-515931-8. google books preview

- Frances Wood (2002). The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. London: Folio Society. ISBN 0-520-24340-4. google books preview

- Zhao Feng (2004). "Wall hanging with centaur and warrior". China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200–750 A.D. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-1-58-839126-1. pdf online