Saskatchewan Co-operative Elevator Company

|

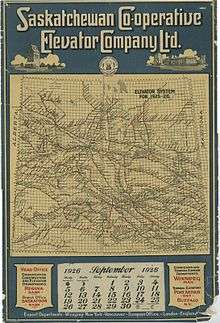

SCEC Calendar - 1926 | |

| Farmers' cooperative | |

| Industry | Grain |

| Founded | 1911 |

| Defunct | 1926 |

| Headquarters | Canada |

Area served | Saskatchewan |

The Saskatchewan Co-operative Elevator Company (SCEC) was a farmer-owned enterprise that provided grain storage and handling services to farmers in Saskatchewan, Canada between 1911 and 1926, when its assets were purchased by the Saskatchewan Wheat Pool.

Background

In the early 20th century wheat farming was expanding fast in the Canadian prairies. Saskatchewan had 13,445 active farms in 1901 covering 600,000 acres (240,000 ha). By 1911 the province had 95,013 farms covering 9,100,000 acres (3,700,000 ha), mostly growing wheat. By 1916 there were 104,006 farms with 14,000,000 acres (5,700,000 ha) of cultivated land.[1] For years the prairie farmers complained of unfair treatment and lack of true competition between the existing line elevator companies, who owned the grain elevators where the grain was stored before being loaded into railway cars.[2] In response to these complaints the Manitoba Grain Act was passed in 1900. The act was well-meaning, but at first was ineffective, and a series of amendments were needed to iron out the flaws.[3]

The Saskatchewan Co-operative Elevator Company (SCEC) had its roots in agitation by the agrarian reformer Edward Alexander Partridge of Sintaluta. The organization meeting for the Grain Growers' Grain Company (GGGC) was held in Sintaluta, Manitoba on 27 January 1906, with Partridge as the first president. The GGGC was a cooperative marketing company, but at first did not own elevators.[4] In 1908 Partridge published the "Partridge Plan" in which he advocated many reforms to the structure of the grain industry, including government ownership of elevators. Under pressure, the Manitoba government purchased elevators in 1910, but the operation was not successful.[2] The elevators were leased by the GGGC in 1912.[4]

Foundation

In Saskatchewan premier Thomas Walter Scott arranged for a Royal Commission on Elevators in 1910. The commission recommended a system where the elevators would be cooperatively owned by the farmers rather than by the government. In 1911 legislation was passed by which the Saskatchewan Co-operative Elevator Company (SCEC) was incorporated to run elevators under this model.[2] The SCEC was a joint-stock cooperative company whose shares would be sold only to farmers, who could not buy more than ten shares each. The government guaranteed the company's credit.[5] The SCEC was to provide elevator services for local farmers, and later expanded into selling grain.[6] Farmers could buy shares with nominal value of CAN$50 for just CAN$7.50. The remainder of the company's capital requirements came from a government-guaranteed loan that the SCEC would repay from its income.[2] John Archibald Maharg (1872–1944) was the first president, holding office until 1923.[7]

History

The SCEC built forty elevators in 1911 and leased six. It built 93 elevators in 1912. In 1913 the Alberta Farmers’ Co-operative Elevator Company (AFCEC) was created using the same model. By 1916 the SCEC was operating 190 elevators, and by 1917 had 230.[2] In 1912 the GGGC had also entered the elevator business when it began to operate 135 country elevators leased from the government of Manitoba.[4] In 1917 the GGGC merged with the AFCEC to form the United Grain Growers (UGG).[8] The SCEC was involved in the merger discussions, but in the end decided not to join the UGG.[9] By 1920 the SCEC had 318 licensed elevators, and was the largest operator of grain elevators on the prairies, ahead of the UGG. By the mid 1920s it had more than 400 elevators.[2]

The SCEC was closely aligned with the Saskatchewan Grain Growers' Association (SGGA), a farmer's group, and with the Liberal Party of Saskatchewan. Maharg, president of the SCEC was also president of the SGGA, and in 1921 was provincial minister of agriculture in the Liberal government. Charles Avery Dunning, the first manager of the SCEC, was later premier of Saskatchewan. J. B. Musselman, an influential Liberal and former secretary of the SCEC, was given a position in the SCEC when he was forced to leave the SGGA by reformers. The SCEC's relationship with the Liberals drew criticism from those who felt that a cooperative should be politically neutral, particularly from those who did not support the Liberals.[2] The SCEC drew criticism for being too conservative, unwilling to expand from running elevators into marketing grain. Its directors were elected at central meetings, so did not represent local needs.[2]

The SCEC was highly profitable. It paid 8% dividends between 1917 and 1924, and annual bonuses that ranged from CAN$0.50 and CAN$4.50 a share. However, it did not pay patronage dividends to non-shareholding farmers.[5] Instead it used its profits to pay for expanding its facilities. It was therefore not a true cooperative. The SCEC alienated the poorer farmers. One of them noted, "Inasmuch as most of the pioneer settlers are too poor to hold shares, it is doubtful if it [SCEC] has helped them much, except as a powerful and keen competitor with other firms." The poorer farmers saw the SCEC and UGG as no different from the other grain companies apart from the fact that their owners were prosperous farmers.[10]

Wheat pool

Early in 1924 wheat pool organizers, inspired by their success in Alberta, began campaigns to sign up farmers in Saskatchewan and Alberta. The two farm organizations in Saskatchewan lent the pool funds, and the provincial government provided a CAN$45,000 advance. The SCEC was violently opposed to organization of a wheat pool in the province, which it saw as a threat to its existence, but could not stop rapid growth in membership. By 6 June 1924 the pool in Saskatchewan had signed up 46,500 contracts covering more than half the acreage in the province. The pool incorporated as the Saskatchewan Co-Operative Wheat Producers. The three provincial pools formed the Canadian Co-Operative Wheat Producers to market the grain.[11]

The SCEC raised difficulties about letting the pool use its elevators, so the pool's leaders made arrangements with private companies, and then started to build its own. In 1925 the pool offered to buy the SCEC's elevators. At the December annual meeting of the SCEC the farmer delegates overrode the board, and forced the SCEC to consider the offer. A special meeting of members in April 1926 voted to sell by 366 to 77. The 451 country elevators and three terminals were valued by arbitrators at CAN$11 million. The SCEC owners received $155.84 per share, a good profit on their CAN$7.50 investment.[2]

References

- ↑ Porter 2008, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Fairbairn 2014.

- ↑ Friesen 2012.

- 1 2 3 Archives of United Grain Growers, U of M.

- 1 2 Solberg 1985, p. 139.

- ↑ Dodwell 1929, p. 607.

- ↑ Dale-Burnett 2014.

- ↑ Fairbairn 2014c.

- ↑ Fairbairn 2014b.

- ↑ Solberg 1985, p. 140.

- ↑ Solberg 1985, p. 199.

Sources

- "Archives of United Grain Growers". Archives of the Agricultural Experience. University of Manitoba. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- Dale-Burnett, Lisa (2014). "MAHARG, JOHN ARCHIBALD (1872– 1944)". Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. University of Regine. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- Dodwell, Henry (1929). The Cambridge history of the British Empire. CUP Archive. GGKEY:RPCX9953HTH. Retrieved 2014-09-16.

- Fairbairn, Brett (2014). "SASKATCHEWAN CO-OPERATIVE ELEVATOR COMPANY (SCEC)". Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. University of Regina. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- Fairbairn, Brett (2014b). "GRAIN GROWERS' GRAIN COMPANY". Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 2014-09-15.

- Fairbairn, Brett (2014c). "UNITED GRAIN GROWERS (AGRICORE UNITED)". Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan=. Retrieved 2014-09-12.

- Friesen, Ron (2012-04-07). "Fair treatment for Western farmers began 100 years ago". Manitoba Co-operator. Retrieved 2014-09-22.

- Porter, Jene M. (2008-01-01). Perspectives of Saskatchewan. Univ. of Manitoba Press. ISBN 978-0-88755-353-0. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- Solberg, Carl E. (1985). The Prairies and the Pampas: Agrarian Policy in Canada and Argentina, 1880-1930. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-6565-7. Retrieved 2014-09-23.