Schutzkorps

| Schutzkorps | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1908–1918 |

| Country |

|

| Type | auxiliary volunteer militia |

| Size | 11,000–20,000 men and 1,600 veterans |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Ademaga Mešić |

The Schutzkorps ("Protection Corps") was an auxiliary volunteer militia established by Austro-Hungarian authorities in the newly annexed province of Bosnia and Herzegovina to track down Bosnian Serb opposition (members of the Chetniks and the Komiti).[1] It was predominantly recruited among the Bosniak population and was known for its part in the persecution of Serbs.[2] They particularly targeted Serb populated areas of eastern Bosnia.[3]

The role of Schutzkorps is a point of debate. Persecution of Serbs conducted by the Austro-Hungarian authorities was the first large-scale persecution of people because of their ethnicity and first incidence of active "ethnic cleansing" in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[4] Some Muslim leaders emphasized that it would be wrong to blame the whole Muslim population of Bosnia and Herzegovina for misdeeds of Schutzkorps, because some Muslims provided help to their Serb neighbors, while some Serbs hid from persecution by applying into Schutzkorps.

Mobilizations

Annexation crisis of 1908–09

The Annexation crisis of 1908–09 erupted on 6 October 1908, when Austria-Hungary announced the annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Many people of Bosnia and Herzegovina were dissatisfied with the events, particularly Serbs who remained in feudal obligations to their Muslim landlords. To prevent their uprising, Austria-Hungary undertook repressive measures against Serb population, conducted by Schutzkorps. Schutzkorps were organized in eleven battalions of volunteers.[5]

In Herzegovina, Schutzkorps avoided taking overly harsh measures against Serb populations near the border of Montenegro to avoid provoking its reaction. Since Gacko and Nevesinje are not near the border, its Serb population was subjected to terror from the Schutzkorps.[6] At the end of October 1908, Serbs of Gacko reported to the government in Sarajevo about the Schutzkorps' terror, but no action was taken to investigate their reports.[7]

Balkan Wars

After the outbreak of the First Balkan War in 1912, anti-Serb sentiment increased in the Austro-Hungarian colonial administration in Bosnia and Herzegovina.[8] Oskar Potiorek, governor of Bosnia and Herzegovina, closed many Serb societies and significantly contributed to the anti-Serb mood before the outbreak of World War I.[9][10] The Government's plans to mobilize Croats and Muslims into Schutzkorps units in case of the war against Serbia were revealed in December 1912 in Banja Luka and caused protests among its Serb population.[11] The idea to revive volunteer units was not implemented.[12]

World War I

Schutzkorps were again established by Potiorek in the prelude of the First World War in 1914, based on the instructions from Austria.[13] The main support for establishment of Schutzkorps came from leaders of the Pure Party of Rights from Zagreb.[14] Initially Schutzkorps consisted of around 11,000 men and 1,600 veterans[15] but their number during the war grew to 20,000.[16] Significant proportion of about 5,000 Schutzkorps were positioned in scarcely populated Herzegovina because Austria-Hungary was concerned that rebellious people of Herzegovina would organize pro-Serb uprising.[17] One of the commanders of Schutzkorps who organized its units in Tešanj region was Ademaga Mešić, who became Ustashe Nazi collaborationist during World War II.[18][19]

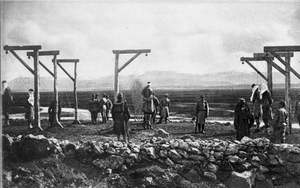

Imprisonment of around 5,500 (700 to 2,200 of them died in prison) and execution of 460 citizens of Serb ethnicity in Bosnia and Herzegovina at the beginning of the World War I heavily relied on Schutzkorps.[1][20] Around 5,200 Serb families were forcibly expelled from Bosnia and Herzegovina.[1] The Schutzkorps shouted anti-Serb slogans and songs, such as "There is no three-fingered cross", while committing their crimes.[21]

Legacy

This was the first persecution of substantial number of citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina because of their ethnicity.[22] Suljaga Salihagić, a Bosnian Muslim, emphasized that not all Muslims were responsible for the activities of Schutzkorps because many provided help to their Serb fellow citizens.[23] Some Muslim leaders denied that Schutzkorps were strictly Muslim and Croat units because many Serbs hid in these units, some even commanded by men of Serb ethnicity.[24]

In 1929, a priest from Trebinje published a book, documenting the acts of persecution, murders, and destruction of houses committed by the Schutzkorps in Trebinje and several other villages of the region.[25]

References

- 1 2 3 Velikonja 2003, p. 141

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 485

The Bosnian wartime militia (Schutzkorps), which became known for its persecution of Serbs, was overwhelmingly Bosniak.

- ↑ Schindler 2007, p. 29

Schutzkorps units were particularly active in Serb areas of eastern Bosnia,

- ↑ Lampe 2000, p. 109

This was first incidence of active "ethnic cleansing" in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

- ↑ Király & Rothenberg 1987, p. 269

Volunteer formations (Schutzkorps) were created during the Bosnian crisis of 1909. Eleven flying battalions were then organized in the province.

- ↑ Vukčević 1985, p. 192

- ↑ Vukčević 1985, p. 192

На терор „шуцкора" жалили су се Срби из Гацка Земаљској влади, али њихове жалбе нијесу узимане у поступак.

- ↑ Frucht 2005, p. 644

The Balkan Wars left Serbia as the region's strongest power. Serbia's relationship with Austria-Hungary remained antagonistic, and the Habsburg administration in Bosnia-Hercegovina became anti-Serb....

- ↑ Frucht 2005, p. 644

...the governor of Bosnia declared state of emergency, dissolved the parliament,.... and closed down many Serb associations....

- ↑ Velikonja 2003, p. 141

The anti-Serb policy and mood that emerged in the months leading up to the First World War were the result of the machinations of Gen. Oskar von Potiorek (1853-1933), Bosnia- Herzegovina's heavy-handed military governor.

- ↑ Drustvo Istoricara Bosne i Hercegovine, Sarajevo (1962). Godisnjak. p. 12.

- ↑ Király & Rothenberg 1987, p. 269

Although it had never took firm ground, the idea of volunteer units was revived in the crisis following the outbreak of the Balkan Wars

- ↑ Dedijer 1974, p. 494

On instructions from Vienna, General Potiorek established an auxiliary militia in Bosnia and Hercegovina— the so-called Schutzkorps, in which he mobilized the scum of town and country. These were given freedom to deal with the Serbian...

- ↑ Dedijer 1987, p. 143

Frankovačke vođe iz Zagreba u stvaranju šuckora 1914. u Bosni i Hercegovini imale su glavnu ulogu.

- ↑ Hugo Schäfer (1934). Österreichs Volksbuch vom Weltkrieg (in German). Verlag Franz Schubert. p. 198. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

Der Schutz im Innern Bosniens und der Herzegowina war der Gendarmerie anvertraut, die von dem „Schutzkorps", bestehend aus 11.000 verläßlichen Männern und dem Veteranenkorps, 1600 Mann, unterstützt wurde.

- ↑ Lampe 2000, p. 109

..Schutzkorps, that grew to 20,000 men.

- ↑ Драга Мастиловић (2009). Херцеговина у Краљевини Срба, Хрвата и Словенаца: 1918-1929. Филип Вишњић. p. 42. ISBN 978-86-7363-604-7. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

Занимљив је податак да је од укупно око 1 1.000 шуцкора у Босни и Херцеговини у самој Херцеговини било око 5.000, а од тога у источној Херцеговини око 3.000. То значи да је 45% свих шуцкора било ангажовано у Хер- цеговини

- ↑ skupština, Yugoslavia. Narodna (1936). Stenografske beleške Narodne skupštine Kraljevine Jugoslavije. p. 234. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

Неки од њих су извршили огроман број насиља и по томе је нознат на злу гласу чувени Адемага Мешић из Тешња, који је одмах у почетку рата организовао читав пук шуцкора и кренуо с њим на Србију.

- ↑ Ribar, Ivan (1951). Politički zapisi. Prosveta. p. 104. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

... Adem-aga Mešić, poznat još iz Prvog svjetskog rata kao organizator takozvanog »šuckora«,...

- ↑ Schindler 2007, p. 29

- ↑ Dedijer 1974, p. 494

While committing their crimes, the Schutzkorps sang: an anti-Serbian song: "There is no three-fingered cross."

- ↑ Velikonja 2003, p. 141

For the first time in their history, a significant number of Bosnia Herzegovina's inhabitants were persecuted and liquidated for their national affiliation. It was an ominous harbinger of things to come.

- ↑ Tomasevich 2001, p. 485

Salihagić, a Bosniak who considered himself a Serb, protested the blanket accusations that all Bosniaks were responsible for the activities of Schutzkorps...

- ↑ Banac 1988, p. 367

- ↑ Popović, Vladimir J. (28 June 1929). Patnje i žrtve Srba sreza Trebinjskoga 1914. - 1918. (in Serbo-Croatian). Trebinje. Archived from the original (Transcript) on 3 May 2006. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

Sources

- Banac, Ivo (1988). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9493-2. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- Dedijer, Vladimir (1974). History of Yugoslavia. McGraw-Hill Book Co.

- Dedijer, Vladimir (1987). Vatikan i Jasenovac: dokumenti. Rad. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- Frucht, Richard C. (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- Király, Béla K.; Rothenberg, Gunther E. (1987). War and Society in East Central Europe: East Central European Society and the Balkan Wars. Brooklyn College Press. ISBN 978-0-88033-099-2. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- Lampe, John R. (2000). Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77401-7.

- Schindler, John R. (2007). Unholy Terror: Bosnia, Al-Qa'ida, and the Rise of Global Jihad. Zenith Imprint. ISBN 978-1-61673-964-5.

- Tomasevich, Jozo (2001). War and Revolution in Yugoslavia: 1941 - 1945. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7924-1. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- Velikonja, Mitja (2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-226-3.

- Vukčević, Luka (1985). Crna Gora u bosansko-hercegovačkoj krizi: 1908-1909. Istorijski institut SR Crne Gore.