Seth Warner

| Seth Warner | |

|---|---|

|

The Seth Warner statue at the Bennington Battle Monument | |

| Born |

May 17, 1743 Roxbury, Connecticut (then a part of Woodbury) |

| Died |

December 26, 1784 Roxbury, Connecticut |

| Buried at | Seth Warner Burial Site, Roxbury, Connecticut |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1775–1780 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | Green Mountain Boys, officially known as Warner's Regiment (1775–1776) and Warner's Additional Regiment (1776–1780) |

| Battles/wars |

Capture of Fort Ticonderoga Capture of Fort Crown Point Battle of Longueuil Battle of Hubbardton Battle of Bennington |

| Relations | Remember Baker, Olin Levi Warner |

Seth Warner (May 17, 1743 [O.S. May 6, 1743] – December 26, 1784) was a Revolutionary War officer from Vermont who rose to rank of Continental colonel and was often given the duties of a brigade commander. He is best known for his leadership in the capture of Fort Crown Point, the Battle of Longueuil, the siege of Quebec, the retreat from Canada, and the battles of Hubbardton and Bennington.[1]

Before the war, he was a captain in the Green Mountain Boys. He was outlawed by New York but never captured.

In the final years of the war, he remained loyal to the United States while the independent state of Vermont negotiated separately with the British.[2]

Early life

Seth Warner was born on the Connecticut frontier in hilly western Woodbury, now Roxbury. He was the fourth of ten children born to Dr. Benjamin Warner and Silence Hurd Warner.[3] His grandfather was Dr. Ebenezer Warner.[4]

Although Warner was not related to Ethan Allen, both men were cousins of Remember Baker, another notable Green Mountain Boy captain.[5]

An early historian wrote that Warner was “a fortunate and indefatigable hunter."[6]

As a teenager he served for two summers in the French and Indian War.[7]

Warner had a common school education. He learned the rudiments medicine from his father. A 1795 account of his life asserts that he had “more information of the nature and properties of the indigenous plants and vegetables, than any other man in the country” and “administered relief in many cases, where no other medical assistance could at that time be procured.”[8]

In 1763 his father purchased land in Bennington, now in the state of Vermont, a town that was chartered by a grant from the colonial governor of New Hampshire, Benning Wentworth. Beginning in the mid-1760s, New York asserted that the boundary of the colony extended to the Connecticut River and the New Hampshire Grant charters were illegitimate.

It is likely the Warner family worked their land in the New Hampshire Grants for two summers before settling full-time in 1765. Seth Warner was chosen highway surveyor and then captain of the town’s militia company.[9][10]

Green Mountain Boy

During the land dispute with New York, Warner was a captain in the Green Mountain Boys, sometimes called the Bennington Mob, a militia organization that defended settlers in the New Hampshire Grants against New York authority. Warner was second in command to Ethan Allen, who was spokesman and colonel-commandant, but Warner often acted independently.[11]

The largest confrontation between New York and the New Hampshire Grants took place at James Breakenridge’s farm in North Bennington on July 18, 1771. Commanding the Bennington militia, Warner fortified Breakenridge’s house and property against a large posse from Albany, New York, sent to evict the settler. No shots were fired, and the posse was turned back.[12]

Warner was outlawed by New York after he struck New York Justice of the Peace John Munro with the flat of his cutlass, following Munro’s attempt to arrest Warner’s cousin Remember Baker.

But despite the violence, Warner gained a reputation as the Green Mountain Boy leader most likely to grant mercy to a New York settler.[13] In one case, rather than burn a New Yorker’s house, he allowed him to remove the roof and then replace it once he had bought a New Hampshire Grant title.[14]

American Revolution

Ticonderoga and Crown Point

On May 8, 1775, a council of officers appointed Warner third in command after Ethan Allen and James Easton of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, of an expedition to capture Fort Ticonderoga. But Warner and the men he had recruited were left on the east shore of Lake Champlain as a rear guard while Allen and newly arrived Colonel Benedict Arnold surprised the garrison on the morning of May 10.[15]

A day later, Warner captured Crown Point, 13 miles (21 km) to the north. The fort, once the largest British fortification in North America, was in ruins and was garrisoned by only nine soldiers. But Crown Point still held 111 cannon, the best of which were taken to Ticonderoga. During the following winter, artillery colonel Henry Knox, acting under orders from George Washington, hauled guns from Lake Champlain to Boston.[16]

Following the capture of the forts, Warner accompanied Allen to St. John (today’s Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Québec), a British outpost on the Richelieu River, the outlet of Lake Champlain. Arnold had successfully raided the outpost, destroying supplies and seizing a British sloop, but had sailed away. Allen attempted to hold the outpost but was driven off by British reinforcements.[17]

Selection as commander

On June 23, 1775, Allen and Warner appeared before the Continental Congress in Philadelphia to ask that the Green Mountain Boys be recognized as a regiment. Congress recommended to the Provincial Congress of New York that they “embody them among the Troops you shall raise.”[18] Although New York was hesitant to incorporate men who had opposed them in the land dispute, the provincial congress established the regiment under the command of a lieutenant colonel and a major.[19] Most leaders, including Major General Philip Schuyler, commander of the Northern Department, assumed that Allen would lead the regiment.

A convention of New Hampshire Grant leaders was held at Cephas Kent’s tavern in Dorset on July 26, 1775. Warner was selected as lieutenant colonel by a vote of 41 to five.[20] No reasons for the action were given in the minutes. Soon afterwards Ethan Allen wrote, “How the old men came to reject me, I cannot conceive, inasmuch as I saved them from the encroachments of New-York.”[21]

Historians debate the reasons for the selection. Was the vote a response to Allen’s mistakes during the spring campaign on Lake Champlain? Did Allen’s unconventional Deist religious beliefs play a role? Did the delegates see Warner as a steadier and less impetuous leader?[22]

The new regiment, unofficially called the Green Mountain Boys, was known in most returns and reports as Warner’s Regiment. It should not be confused with the pre-Revolutionary War Green Mountain Boys. Although the regiment was based in the western New Hampshire Grants, some recruitment took place outside that area.[23]

The invasion of Canada

Along the St. Lawrence River, fall 1775

In the late summer and fall of 1775, an American army under command of Philip Schuyler and then Brigadier General Richard Montgomery invaded Canada by way of Lake Champlain. By then the British had refortified St. John, and the Americans besieged the fort on the Richelieu River.

In mid-September Warner and his regiment saw action near Fort St. John before being stationed along the St. Lawrence River where they kept watch on Montreal and the British shipping.[24]

Warner’s headquarters became the Château fort de Longueuil, a late 17th century “castle” with turrets in the village of Longueuil.

On October 30, Governor General Guy Carleton and approximately 800 men in 35 to 40 boats attempted to cross the St. Lawrence and relieve Fort St. John. The landing was opposed by Warner, commanding his regiment and companies from the 2nd New York, totaling about 350 men. The American victory in the Battle of Longueuil led directly to the surrender of Fort St. John on November 3.[25]

Montreal surrendered on November 13, and Warner was part of the forces that entered the city. General Montgomery ordered Warner’s Regiment to prepare to go by canoe to Quebec, the last British stronghold in Canada. But the regiment had received no winter clothing or equipment, and many men were reluctant to stay in Canada. In the end, Montgomery grudgingly permitted the regiment to return home to equip themselves for the next campaign.[26][27][28]

The siege of Quebec, winter 1776

Warner and his regiment were at home when General Montgomery was killed and Benedict Arnold was wounded in a predawn attack on Quebec, December 31, 1775.

Brigadier General David Wooster, commanding in Montreal, wrote to Warner calling for reinforcements. “You, sir, and the Green-Mountain corps are in our neighborhood. Let me beg of you, to collect as many men as you can, five, six, or seven hundred, and if you can, and some how [sic] or other, convey into this country,and stay with us till we can have relief from the Colonies.”[29] Within a few days, companies from the southwest New Hampshire Grants and western Massachusetts had formed and were marching north. They crossed the length of frozen Lake Champlain to St. John, visited Montreal for supplies, and then headed east to Quebec, a distance of at least 400 miles (640 km).[30]

The American army besieging Quebec was devastated by a smallpox epidemic. Warner permitted, perhaps even encouraged, his men to inoculate, or to introduce smallpox pus into an incision, usually causing a milder case of the disease.[31] The controversial procedure, which could spread the deadly disease to healthy people, was against General Arnold’s orders and subject to the severest penalties.[32]

By early April many in the regiment were returning to health. The regiment supplied a large portion of the effective soldiers before the city. Other men were stationed on Île d'Orléans, a 20 by 3 miles (32.2 by 4.8 km) long island in the St. Lawrence east of Quebec.[33]

Retreat from Canada, spring 1776

With the arrival of three British ships of war on May 6, 1776, the American army abandoned the siege of Quebec and began a retreat.

Details of Warner’s role are scanty, but in a 1795 sketch of his life, pastor and newspaper editor Samuel Williams wrote, “Warner chose the most difficult part of the business, remaining always with the rear, picking up the lame and diseased, assisting and encouraging those who were the most unable to take care of themselves, and generally kept but a few miles in advance of the British, who were rapidly pursuing the retreating Americans from post to post. By steadily pursuing this conduct he brought off most of the invalids; and with his corps of the infirm and diseased he arrived at Ticonderoga, a few days after the body of the army had taken possession of the post.”[34]

Formation of a new regiment, 1776–1777

On July 5, 1776, the Continental Congress resolved that “a regiment be raised out of the officers who served in Canada” with Seth Warner as colonel. This new regiment was officially known as Warner’s Additional Regiment.[35]

On July 24, Warner attended a convention in Dorset, one of a series of meetings held as the New Hampshire Grants gradually formed an independent government. Warner and all but one delegate pledged “at the Risque of our Lives and fortunes to Defend, by arms, the United American States against the Hostile attempts of the British Fleets and Armies, until the present unhappy Controversy between the two Countries shall be settled.”[36]

Recruitment for the new regiment was slow. In September, Warner and captains Wait Hopkins and Gideon Brownson traveled to Philadelphia to petition the Continental Congress to reimburse them for expenses from the Canada campaign.[37] Instead, the congress referred them back to the commissioners of the Northern Department,who also refused to act. In addition, Philip Schuyler would not release recruitment money until December.

In the fall, American forces on Lake Champlain at Ticonderoga and Mount Independence prepared to meet a British invasion. In October after the Battle of Valcour Island, Warner mustered the militia of the New Hampshire Grants and led them to the Lake Champlain forts. Major General Horatio Gates wrote, “I much approve of your zeal and activity in spiriting up the Militia to come and defend their country. They cannot be too soon here.”[38]

In January 1777, the first men from Warner’s Additional Regiment were quartered on Mount Independence.

In May 1777, Warner led a force of militia from Schenectady, New York, and the New Hampshire Grants on a raid into the Loyalist stronghold of Jessup’s Patent, centered at today’s Lake Luzerne, New York. As a result of the hardships of this raid, Warner's health began to fail.[39]

Burgoyne's invasion, 1777

The American retreat from Ticonderoga

By June 15, 1777, Warner’s undersized regiment at the Lake Champlain forts had grown to 170 enlisted men and a total of 228.[40]

As an army of 8000 under command of Lieutenant General John Burgoyne sailed south on Lake Champlain, Warner’s men joined the fatigue parties to prepare the forts for attack. Once the siege began, the regiment occupied the so-called French Lines, 0.75 miles (1.2 kilometers) to the north of Fort Ticonderoga.

In late June, commander Major General Arthur St. Clair ordered Warner to raise the militia of the New Hampshire Grants to counter Indian raids along Otter Creek. “Attack and rout them, and join me again as soon as possible,” St. Clair told him. The situation at the forts worsened quickly.[41]

On July 1 from Rutland, Vermont, Warner wrote to the leaders of the independent state, then meeting in a constitutional convention in Windsor on the Connecticut River, calling upon them for men and supplies. “Their lines are so much in want of Men, I should be glad that a few hills of Corn unhoed should not be a Motive sufficient to detain Men at home, considering the Loss of such an important Post can hardly be recovered.”

Meanwhile, companies of his regiment fought in a skirmish outside the French Lines on July 2. One of Warner's lieutenants was killed.

On July 3 Warner led about 800 militia into the fortifications.They drove with them 40 head of cattle and numerous sheep. The newly arrived militia made up approximately one-fifth of the garrison.[42]

On July 5 St. Clair and a council of general officers made the decision to abandon the forts.[43] First Ticonderoga and then Mount Independence were evacuated on the night of July 5–6. Colonel Ebenezer Francis of Massachusetts had command of a specially chosen rearguard of 450 that included men from Warner’s Regiment. In the retreat, Warner positioned himself near the rear of the army as it marched east into Vermont on the Mount Independence-Hubbardton Military Road. They were pursued by 850 British soldiers under command of Brigadier General Simon Fraser.[44]

Battle of Hubbardton

On the afternoon of July 6, the main body of the retreating army passed through Hubbardton, a frontier settlement about 20 miles from Mount Independence. General St. Clair ordered Warner to follow with the rearguard and “to halt about one and a half mile [sic] short of the main body which would remain that night at Castle-Town [Castleton], about six miles from Hubbarton [sic].”[45]

The rearguard under Francis reached Hubbardton in the late afternoon. Warner decided to remain in the settlement that night, telling officers “the men were much fatigued.”[46] About 1100 men were under his command: his own regiment, Francis’s handpicked rearguard, the Second New Hampshire under Colonel Nathan Hale, and several hundred sick and stragglers, who camped in a valley by a small stream.[47] Warner and most of the brigade occupied a hill above the road (today’s Monument Hill at the Vermont State Historic Site).

On July 7, Fraser attacked the men in valley before 7 a.m. and scattered them, but soon met disciplined resistance. The main battle took place on Monument Hill where the advantage seesawed back and forth until the arrival of German troops from the Duchy of Brunswick under command of Major General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel.

Francis was killed, and Warner ordered a retreat over Pittsford Ridge, the road to Castleton having been cut off by British grenadiers.

The Americans suffered by one study 41 killed, 96 wounded, and 234 taken prisoner. In comparison, the British and German casualties were 60 killed and 148 wounded.[48] By 18th-century standards Hubbardton was a British victory, but more recently the battle has been called a “classic example of a rear guard action.” As a result of Hubbardton, Fraser stopped his pursuit of the main American army.[49]

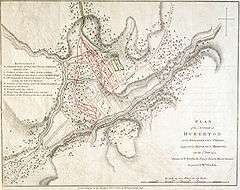

Battle of Bennington

Following the Battle of Hubbardton, Warner and his regiment guarded the frontier north of Manchester, Vermont, with orders from Schuyler to seize cattle and carriages and to arrest “Tories” (Loyalists).[50]

By early August, Continental Major General Benjamin Lincoln and New Hampshire Brigadier General John Stark were in Manchester. Although at odds, they agreed to attack Burgoyne’s rear, marching from Bennington through Cambridge, N.Y. By Schuyler’s orders, Warner was to command Vermont and Massachusetts militia, Vermont ranger companies, and his own regiment, which remained on the frontier under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Safford.[51] The American army in Vermont was still growing and would exceed 2000.

The expedition gathered in Bennington. On August 13 Stark learned that an enemy force was marching towards them. (Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum had more than 800 men under his command, including Brunswickers, Loyalists, Canadians, and Indians.)[52] The two armies skirmished on August 14; it rained August 15.

Although Stark had overall command, Warner, who lived a few miles from the battlefield, helped plan the American attack. On the afternoon of August 16, Vermont militia and ranger companies swung around the Germans and attacked a hilltop fortification from the west. Meanwhile, Warner commanded the left wing which attacked the Tory or Loyalist Redoubt on the east side of the Walloomsac River.

The American victory seemed to be complete and the exhausted militia had turned to celebration when more than 600 German reinforcements under Lieutenant Colonel Heinrich Breymann advanced from the west. Warner took command during this engagement. His own regiment reached the battlefield in time to play a decisive role. Stark wrote, “We pursued them till dark; but had day light lasted one hour longer, we should have taken the whole body of them.”[53]

In all, German and Loyalist casualties totaled 207 dead and 700 taken prisoner.[54] American casualty figures are less exact, but about 30 killed and 50 wounded.[55]

Stark reported to General Gates, “Colonel Warner’s superior skill in the action was of extraordinary service to me; I would be glad if he and his men could be recommended to Congress.”[56]

Burgoyne’s surrender

Warner was active after the Battle of Bennington, but many details are lost. He remarked once that until Burgoyne’s surrender he was “so continually on the alert that for seventeen days and nights he never took off his boots . . . a single time.”[57]

His regiment and Vermont ranger companies participated in a raid upon Ticonderoga and Mount Independence, using the outpost in Pawlet as a staging area. The action is usually called “Brown’s Raid,” after John Brown of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, a former Continental officer who had served closely with Warner during the invasion of Canada. On September 18, two hundred ninety-three British soldiers were captured, and 118 American prisoners, most captured at the Battle of Hubbardton, were set free.[58][59]

Warner’s partnership with Stark continued. The two, accompanied by New Hampshire and Vermont militia and Warner’s Regiment, operated to the north of Saratoga (today’s Schuylerville), N.Y. They crossed the Hudson River and by the morning of October 13 had occupied a narrow pass between a marsh by the river and a hill that is now called Stark’s Knob. As a result, Burgoyne lost his final opportunity to retreat and surrendered.[60][61]

After the Saratoga campaign, 1778–1780

In the winter following the victory at Saratoga, Gates promoted a second invasion of Canada, which came to nothing. Warner was prominent in these plans.[62]

On March 20, 1778, the Vermont assembly named Warner the only brigadier general in the new state.[63] But tension increased between independent Vermont and the United States, putting Warner and his Continental regiment in a difficult position. From 1778 to 1780, Warner’s Regiment served largely along the upper Hudson River and at Fort George at the head of Lake George. Warner was increasingly sick with a leg ailment and absent.

On September 6, 1780, after a visit to his regiment at Fort George, he was seriously wounded in an ambush by Indians. Two of his officers were killed.[64]

The regiment at Fort George was destroyed on October 11, 1780, in a raid under the command of Major Christopher Carleton. By the British count, 27 Americans were killed and 44 taken captive.[65][66] The regiment was disbanded at the end of 1780 and Warner retired from the service.

Later life

In the late 1770s and early 1780s, Ethan Allen, who had spent three years as a prisoner of war, his brother Ira, and Governor Thomas Chittenden dominated Vermont politics, and Warner’s influence waned.

Beginning in 1780, Vermont negotiated with the British in Canada. Historians debate the real goal of what has been called the “Haldimand Negotiations” after Frederick Haldimand, governor of Quebec. Were the Vermont leaders genuinely interested in reunification with Great Britain or were they pretending to discuss the possibility in order to avoid war?[67]

In March of 1781, Warner confronted Ethan Allen, who then publicly admitted to limited contact with the British about prisoner exchange.[68]

The negotiations continued in secret with Warner in opposition. Loyalist and British negotiator Justus Sherwood warned his superiors, “I fear the Benningtonites, especially the two mob Colonels; Warner and [Samuel] Herrick, will find means to overturn the whole system. I wish those two rascals could be put quietly out of the way for they are too cunning to be brou’t [sic] here, where the tongues of surmises are so busy.”[69]

With his health failing, Warner returned to Woodbury where he died on December 26, 1784 at age 41.[70][71] He was financially insolvent and, except for small holdings for his widow, his property was sold to pay creditors.[72]

Legacy

Seth Warner has always been in the shadow of the more flamboyant Ethan Allen, although he has gained some recognition.

The state of Vermont eventually granted 2,000 acres (8 km²) in the northeast corner of Vermont, still called Warner's Grant, to his family[73] The grant, also called Warner's Gore, remains uninhabited and undeveloped.[74][75]

Prominent nineteenth-century Vermont writers, including Rowland E. Robinson, argued that in honoring its early heroes the state had neglected Warner.[76] Under the fictional name of Charles Warrington, Warner was the hero of the popular romance The Green Mountain Boys, published in 1839 by Daniel Pierce Thompson. In the preface to the second edition of this novel, Thompson wrote that if he could he would make several changes "particularly in the appellation of one of the most conspicuous personages, Charles Warrington, whose prototype was intended to be the chivalrous Colonel Seth Warner."[77]

A 21-foot tall granite obelisk honoring Warner was dedicated on the town green in Roxbury, Connecticut, in 1859. Warner’s remains were reburied beneath the memorial.[78][79]

In the late 1800s, the Bennington Battle Monument was built.[80] In 1911 a statue of Warner was placed on the monument grounds.[81][82] The likeness of the statue is imaginary, as no portrait or other illustration of Warner was made during his life.[83]

The site of Warner's Bennington house is designated by a commemorative marker.[84]

Family

Seth Warner had nine siblings: Hannah, Benjamin II (Doctor), Daniel, John (Doctor), Reuben (Doctor), Elijah, Asahel, David, and Tamar.[85]

A brother, Daniel Warner, was killed in the Battle of Bennington.[86]

A brother, John Warner (1745–1819), was a captain in Herrick’s Rangers during the Revolutionary War and later an early settler in St. Albans, Vermont.[87]

Warner married Esther (occasionally appears as Hester) Hurd (1748–1816) of Lanesboro, Massachusetts, in June of 1766. The couple had four children: Israel (1768–1862), Seth (1771–1776), Abigail Meacham (1774–1862), and Seth (1777–1854).[88]

Warner's great-grandnephew Olin Levi Warner was a well-known nineteenth-century sculptor.[89]

Notes

- ↑ Thompson, Charles Miner. Independent Vermont. Houghton Mifflin Company (1942), pp. 329–34; Chipman, Daniel. Memoir of Colonel Seth Warner. L.W. Clark (1848); Williams, Samuel. "Historical Memoirs of Colonel Seth Warner," The Natural and Civil History of Vermont. Burlington (1809), vol. 2, pp. 445–50.

- ↑ Jellison, Charles A. Ethan Allen: Frontier Rebel. Syracuse University Press (1969), pp. 266–67.

- ↑ Cothren, William. History of Ancient Woodbury, Connecticut. Waterbury, Conn. (1854), p. 753.

- ↑ Petersen, James E. Seth Warner. Middlebury, Vt. (2001), p. 14

- ↑ Jellison,Charles. Ethan Allen: Frontier Rebel. Syracuse University Press (1969). pp. 39–40

- ↑ Williams, Samuel. "Historical Memoirs of Colonel Seth Warner," Natural and Civil History of Vermont, 2nd edition, Burlington (1809), vol. 2. p. 445. The article originally appeared in The Rural Magazine in 1795.

- ↑ Rolls of Connecticut Men in the French and Indian War, 1755–1762, Collections of the Connecticut Historical Society 10, Hartford (1905) vol. 2, pp. 207–08, 349.

- ↑ Williams, p. 445.

- ↑ Early Bennington Town Records, May 20, 1766, Bennington Town Clerk

- ↑ Jellison, p. 61.

- ↑ Thompson, Independent Vermont. pp. 119–23, 146–53.

- ↑ Chipman, p. 20.

- ↑ Thompson, pp. 330–31

- ↑ Petersen, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ "Edward Mott to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress," May 11, 1775, The Bulletin of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum, vol. 13, No. 5 (1977), p. 335.

- ↑ Benedict Arnold to the Massachusetts Committee of Safety, May 19, 1775, Naval Documents of the American Revolution, vol. 1. United States Printing Office (1964), pp. 366–67.

- ↑ Jellison. Ethan Allen. pp. 128-31.

- ↑ Journals of the Continental Congress, June 23, 1775, vol. 2, p. 105.

- ↑ New-York Provincial Congress, July 4, 1775, American Archives, Ser. 4., vol. 2. pp. 1338–39.

- ↑ Records of the Council of Safety and Governor and Council of the State of Vermont (1873), vol. 1, pgs. 6–10.

- ↑ Ethan and Ira Allen: Collected Works, J. Kevin Graffagnino, ed. (Benson, Vt.: Chaldize Publications,1992), vol. 1, p. 47.

- ↑ Jellison, pp. 144–45.

- ↑ Shalhope, Robert E. Bennington and the Green Mountain Boys: The Emergence of Liberal Democracy in Vermont, 1760–1850. The Johns Hopkins University Press (1996), p. 165.

- ↑ “Diary of Captain John Fassett, Jr. (1743–1803) When a First Lieutenant of ‘Green Mountain Boys,’” Harry Parker Ward, The Follett-Dewet Fassett-Safford Ancestry of Captain Martin Dewey Follett and his wife Persis Fassett, (1896), pp. 220–25.

- ↑ Smith, Justin H. Our Struggle for the Fourteenth Colony: Canada and the American Revolution. G. P. Putnam's Sons (1907), vol. 1, pp. 449–55.

- ↑ “Diary of Captain John Fassett, Jr., p. 237.

- ↑ Richard Montgomery to Philip Schuyler, December 5, 1775, Correspondence of the American Revolution; Being Letters of Eminent Men to George Washington, from the Time of His Taking Command of the Army to the End of His Presidency, Jared Sparks, ed., Vol 1, (1853), p. 493.

- ↑ “Diary of Captain John Fassett, Jr., p. 237.

- ↑ Wooster to Warner, January 6, 1776, American Archives, Ser. 4, vol. 4, pp. 588–89, 766.

- ↑ Chipman, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Thompson,Independent Vermont, pp. 333–34.

- ↑ General Orders, March 15, 1776, American Archives, Ser. 4, Vol. 5, p. 551; Return of Troops, March 30, 1776, American Archives, Ser. 4, Vol.5, p. 550.

- ↑ Doyen Salsig, ed., Parole: Quebec; Countersign: Ticonderoga, Second New Jersey Regimental Orderly Book, 1776 (London: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1980), pp. 59–98.

- ↑ Williams, Samuel. “Historical Memoirs of Colonel Seth Warner,” The Rural Magazine: Or, Vermont Repository. Rutland (1795), reprinted in Natural and Civil History of Vermont, 2nd edition (Burlington, 1809), vol. 2, p. 447.

- ↑ July 5, 1776, Journals of the Continental Congress, American Memory, Library of Congress.

- ↑ Records of the Council of Safety and Governor and Council of the State of Vermont (1873). Vol. 1, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Memorial of Warner, Hopkins, and Brownson, September 10, 1776, American Archives, Ser. 5, Vol. 2, p. 274.

- ↑ Gates to Warner, October 21, 1776, American Archives, Ser. 5, Vol. 2, p. 1169.

- ↑ Petition to the Congress, July 7, 1786, as found in George Frederick Houghton, “The Life and Services of Col. Seth Warner,” Addresses Delivered before the Legislature of Vermont, October 20, 1848. Burlington (1849), p. 66.

- ↑ Proceedings of the General Court Martial, held at White Plains in the state of New-York by order of his Excellency General Washington for the Trial of Major General St. Clair, August 25, 1778, New-York Historical Society Collections vol.13 (1880), p. 29.

- ↑ St. Clair Papers, p. 411.

- ↑ St. Clair Court Martial, 40.

- ↑ St. Clair Court Martial, 33–34, 37.

- ↑ Wheeler, Joseph L. and Mabel A. The Mount Independence-Hubbardton 1776 Military Road. Benson, Vt. (1968).

- ↑ St. Clair Court-Martial. p. 113.

- ↑ St. Clair Court-Martial, p. 87.

- ↑ Williams, John. The Battle of Hubbardton: The American Rebels Stem the Tide. Vermont Division for Historic Preservation (1988), p. 60.

- ↑ Williams, p. 65.

- ↑ Williams, p. 5.

- ↑ Collections of the VT Historical Society. Vol. 1, p. 186.

- ↑ Moore, Howard Parker. A Life of General John Stark of New Hampshire. New York (1949), p. 287.

- ↑ Gabriel, Michael P. The Battle of Bennington: Soldiers & Civilians. History Press (2012), p. 18.

- ↑ Collections of the Vermont Historical Society. Vol. 1, p. 207.

- ↑ Gabriel. p. 28.

- ↑ Peckham. The Toll of Independence: Engagements & Battle Casualties of the American Revolution. University of Chicago Press (1974), p. 38.

- ↑ Collections of the Vermont Historical Society. Vol. 1, p. 207.

- ↑ Boardman, David S. "Reminiscences of Colonel Seth War," Historical Magazine (July 1860), p. 201.

- ↑ "John Brown and the Dash for Ticonderoga." The Bulletin of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum, vol. 2, no.1 (Jan 1930).

- ↑ Hoyt, Edward A. and Kingsley, Ronald F. "The Pawlet Expedition, September 1777," Vermont History (Summer/Fall 2007).

- ↑ Stone, William. Journal of Captain Pausch. Albany, Joel Munsell's Sons (1886), pp. 153–54.

- ↑ Stone, William L. Memoirs and Letters and Journals of Major General Riedesel. Albany, J. Munsell (1868), p. 179.

- ↑ Chipman. p. 73.

- ↑ Slade, William. Vermont State Papers. Middlebury, Vt. (1823). p. 262.

- ↑ Holden, A. W. History of the Town of Queensbury. Joel Musell (1874), p. 304.

- ↑ Watt, Gavin K. The Burning of the Valleys. Dundurn Press (1997), pp. 103–05.

- ↑ Cometti, Elizabeth, editor. The American Journals of Lt John Enys. Syracuse University Press (1976), p. 51.

- ↑ Wilbur, James Benjamin. Ira Allen: Founder of Vermont,1751–1814. Houghton Mifflin (1928), lengthy discussion in volume 1;Jellison, Ethan Allen: Frontier Rebel, pp. 230–74.

- ↑ Jellison, pp. 266–67.

- ↑ Wilbur, p. 386.

- ↑ William R. Denslow, 10,000 Famous Freemasons from K to Z, 2004, Volume 3, p. 297

- ↑ State of Vermont, Records of the Council of Safety and Governor, Volume 3, 1875, p. 503

- ↑ Petersen, Seth Warner, p. 161.

- ↑ Vermont Historical Society, Collections of the Vermont Historical Society, Volume 2, 1871, p. 466

- ↑ Walter Hill Crockett, Vermont: The Green Mountain State, Volume 2, 1921, pp. 431–32

- ↑ Unified Towns & Gores of Essex County, Vermont, Local Development Plan, 2011, p. 5

- ↑ Robinson, Rowland E. ''Vermont: A Study of Independence'', Boston: Houghton Mifflin (1892), p. 259

- ↑ Thompson, Daniel P. “Preface to the Second Edition,”'' The Green Mountain Boys'' (1850).

- ↑ Connecticut Monuments.Net

- ↑ Seth Warner at Find a Grave

- ↑ New York Times, Bennington's Great Day: All Ready to Dedicate the Big Battle Monument, August 17, 1891

- ↑ Christian Science Monitor, "Memorial to Colonel Warner", September 29, 1909

- ↑ Boston Evening Transcript, "Honor Revolution Hero: Monument Dedicated at Bennington, Vt. to Seth Warner", August 16, 1911

- ↑ Tim Johnson, Burlington Free Press, "The many faces of Ethan Allen", 2013

- ↑ Bennington Museum, Read the Markers, accessed July 10, 2013

- ↑ Ancient New Haven, Vital Records of New Haven 1649 to 1850. Retrieved by Larry Nathaniel Chadwick Warner (2009). ''Ancient New Haven, Vital Records of New Haven 1649 to 1850'',

- ↑ Joseph Parks, Bennington Historical Society, Bennington Banner, Men of Bennington Who Died in Our Wars, Part I, June 23, 2006

- ↑ Hemenway, Abby Maria.'' The Vermont Historical Gazetteer''. Burlington, Vt. (1871), vol. 2, pt. 1, p. 292.

- ↑ Abigail Meacham to Charles B. Phelps, June 18, 1857, copy in the Bennington Museum; genealogical chart by Kaschub, LeRoy and Hurd, Thaddeus, June 20, 1971, copy in the Bennington Museum.

- ↑ James Terry White, The National Cyclopedia of American Biography, 1898, p. 282

- Attribution

![]() Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Warner, Seth". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Warner, Seth". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.