Sexual racism

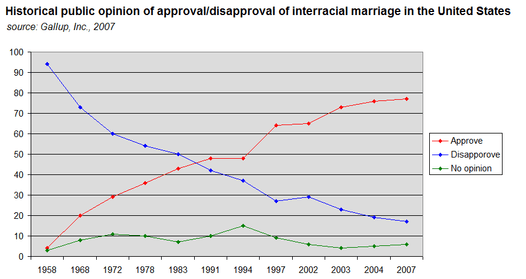

Sexual racism is the "sexual rejection of the racial minority, the conscious attempt on the part of the majority to prevent interracial cohabitation." [1] It is the discrimination between potential sexual or romantic partners on the basis of perceived racial identity. However, not everyone agrees that this should be classified as racism, some argue that distinguishing among partners on the basis of perceived race is not racism at all but a justifiable personal preference.[2] The origins of sexual racism can be explained by looking at its history, especially in the USA, where the abolition of slavery and the Reconstruction Era had significant impacts on interracial mixing. Attitudes towards interracial relationships, and indeed marriage, have increased in positivity in the last 50 years. In 1968, 73% of US citizens disapproved of the right to marry inter-racially, whereas this figure dropped to 17% by 2007, this illustrating the reduction in discriminatory attitudes towards interracial dating.[3] Irrespective of this, there still remains the issue of sexual racism in the online dating world, in that preferences appear to follow a racial hierarchy. The exclusion of races dissimilar to one's own is a main feature of sexual racism, however a reluctance to date inter-racially predominantly spans from the discriminatory views often possessed by those in society, as opposed to purely a same-race individual preference. Moreover, this racial discrimination also deviates into the form of the sexual dehumanisation of individuals of other racial identities. Sharing the basic premise, originating from the 'taboo' nature of interracial relations, individuals of other racial groups are classified as forbidden sexual objects; the result of a racial fetish. This sexualised reductionism is, concurrently, a form of sexual racism.

History

USA

After the abolition of slavery in 1865, the white citizens of America showed an increasing fear of racial mixture.[4] The remnants of the racial divide became stronger post-slavery as the concept of whiteness developed. Unbridled lust threatened the purity of the nation, which increased white anxiety about interracial sex. This can be described through Montesquieu’s climatic theory in his book the Spirit of the Laws, which explains how people from different climates have different temperaments, “The inhabitants of warm countries are, like old men, timorous; the people in cold countries are, like young men, brave." [5] At the time, black women held the jezebel stereotype, which claimed black women often initiated sex outside of marriage and were generally sexually promiscuous.[6] This idea stemmed from the first encounters between European men and African women. As the men were not used to the extremely hot climate they misinterpreted the women’s lack of clothing for vulgarity.[7] Similarly, black men were known for having a specific lust for white women. This created tension, as if white men were having sex with black women because they were more lustful, this meant black men would lust after white women in the same way, this threatened the white male dominance that was apparent at the time, increasing the fear of interracial interactions.

There are a few potential reasons as to why such strong ideas on interracial sex developed. The Reconstruction Era following the Civil War started to disassemble traditional aspects of Southern society. The Southerners who were used to being dominant were now no longer legally allowed to run their farms using slavery.[8] Many whites struggled with this reformation and attempted to find loopholes to continue the exploitation of black labour. Additionally, the white Democrats were not pleased with the outcome and felt a sense of inadequacy among white men. This led to them taking out their frustration on the black population. This radical reconstruction of the South was deeply unpopular and slowly unravelled leading to the introduction of the Jim Crow Laws.[9] These laws reinforced racial segregation as the white population refused to mix with the black population, again undermining the prominent black populace. This increased the sense of white dominance and sexual racism among the Southern people.

There were general heightened tensions following the end of the failed civil war in 1865, and this increased the sexual anxiety in the population. Races did not want to mix, the whites were feeling inadequate and wanted to take back control. The Ku Klux Klan then formed in 1867, which led to violence and terrorism targeting the black population.[10] There was a rise in lynch mob violence where many black men were accused of rape. This was not just senseless violence, but an attempt to preserve ‘whiteness’ and prevent racial blur, the whites wanted to remain dominant and make sure there was no interracial sexual activity. For example, mixed race couples that chose to live together were sought out and lynched by the KKK. The famous case of Emmett Till who was lynched at the age of fourteen for supposedly whistling at a white women shows the prominence of white male anxiety in the 1950’s.[11] When the Jim Crow laws were eventually overturned, it took years for the court to resolve the numerous acts of discrimination.

Heterosexual Community

Sexual racism exists in both the heterosexual and homosexual communities across the globe. There are countless historical and contemporary examples of heterosexual interracial couples that illustrate the former impact of sexual racism, in addition to highlighting how attitudes have changed in the last 50 years.[12] A case that has perhaps received heightened publicity is that of Mildred and Richard Loving. The couple lived in Virginia yet had to marry outside the state due to the anti-miscegenation laws present in nearly half of the US states in 1958. Once married, the pair returned to Virginia, however in the same year were both arrested in their home for the infringement of the Racial Integrity Act, and each sentenced to a year in prison. Before the laws were officially abolished in 2000, the couple attempted to quash the charges, however were met with an ultimatum that led to their short-term relocation to avoid further prejudice.[13] This particular example indicates sexual racism on a large state-wide scale, such that at this time there was increased discrimination against interracial couples, based upon the attitudes that the laws created.

Around a similar time was the controversy surrounding Seretse and Ruth Khama. When they met, Seretse was the chief of an eminent Botswanan tribe, and Ruth an English student. The pair married in 1948 but experienced robust discrimination from the onset, including Seretse’s removal from his tribal responsibilities as chief. For nearly 10 years, Seretse and Ruth lived as exiles in Britain, as the racism towards their relationship remained strong. Britain hoped that holding them would reduce their desire to continue the marriage. Once the couple were allowed home in 1956, they became prominent figures in the human rights and social world, contributing to Seretse’s election as president of Botswana in 1966. After this, they both continued to rebut the laws surrounding interracial marriage.[14]

More recent examples portray the increasingly accepting attitudes of the majority to interracial relationships and marriage. In 2013, Bill de Blasio was elected as Mayor of New York City, accompanied by his wife, Chirlane McCray. The pair are one of the first interracial couples to stand in power side by side. Both de Blasio and McCray are active political figures, and although they are not exempt from racial discrimination, the attitudes of the world to interracial marriage are much more positive and optimistic than in previous decades.[15] Across much of the world, it is ever increasingly the situation that interracial couples can live, marry and have children without prosecution that was previously rife, due to major changes in law along with reductions in discriminatory attitudes. Sexual racism also exists in the heterosexual community in online dating.[16][17][18][19][20]

Online Dating

In the last 15 years, online dating has overtaken previously preferred methods of meeting with potential partners, surpassing both the occupational setting and area of residence as chosen locations. This spike is consistent with an increase in access to the internet in homes across the globe, in addition to the number of dating sites available to individuals differing in age, gender, race, sexual orientation and ethnic background.[21] Along with this, there has been a rise in online sexual racism, whereby partner race is now the most highly selected preference chosen by users when creating their online profiles, displacing both educational and religious characteristics.[22] Research has indicated a progressive acceptance of interracial relationships by White individuals.[23] The majority of White US citizens are not against interracial relationships and marriage,[24] however these beliefs are not illustrated in subsequent marital rates between interracial couples, such that no more than 4% of White US residents will wed outside their own race.[25] In fact, less than 46% of White Americans are willing to date an individual of any other race.[26] Overall, African Americans appear to be the most open to interracial relationships,[27] yet are the least preferred mate by other racial groups.[26] However, regardless of stated preferences, racial discrimination still occurs in online dating.[22]

Each group significantly prefers to date a mate intra-racially. White Americans are the least open to interracial dating, and select preferences in the order of Hispanic Americans, Asian Americans and then African American individuals last at 60.5%, 58.5% and 49.4% respectively.[27] With regards to African American preferences, the order follows a similar pattern, with the most preferred mate belonging to the Hispanic group (61%), followed by White individuals (59.6%) and then Asian Americans (43.5%). Both Hispanic and Asian Americans prefer to date a White individual (80.3% and 87.3%, respectively), and both are least willing to date African Americans (56.5% and 69.5%).[26] In all significant cases, Hispanic Americans are preferred to Asian Americans, and Asian Americans are significantly preferred over African Americans.[27] Hispanic Americans are less likely to be excluded in online dating mate preferences, specifically by White individuals, as they are now viewed as a racial group that has successfully assimilated into White American culture.[28]

In addition to general racism in online dating, there is further exclusion differences between certain genders within racial groups, such that females of any race are significantly less likely to date inter-racially than a male of any race.[29] Specifically, Asian men and Black women face more obstacles to acceptance online.[30] White women are most likely to exclude Asian males, due to their amplified effeminate portrayal in the media.[31][32][33] This exclusion remains present even when considering high earning Asian individuals with an advanced educational background.[27][34][35] Increased education does however influence choices in the other direction, such that a higher level of schooling is associated with more optimistic feelings towards interracial relationships.[36] Furthermore, White males are most likely to exclude Black females, as opposed to females of another race, as they are more often represented undesirably in both their disposition and physical appearance in television broadcasting.[37][38]

Racial attitudes, specifically those concerning interracial relationships, are mediated by the level of exposure experienced by the online user. High levels of previous exposure to a variety of racial groups creates a more accepting attitude.[39] Sexual racism in online dating, in addition to the outside world, is also influenced by the mate selectors area of residence. Those residing in more Southern regions, particularly in American states, are less likely to have been in an interracial relationship, and are unlikely to inter-racially date in the future.[40] Location is also related to the individuals current and previous religious practices; those who engaged in regular religious customs at age 12 are less likely to inter-racially date. Moreover, those from a Jewish background are significantly more likely to enter an interracial relationship than those from a Protestant background, indicating differences in levels of sexual racism present, which translate into the virtual world of online dating.[40]

Homosexual Community

Asian men are often represented in media, both mainstream and LGBT, as being feminized and desexualized. [41] LGBT Asian men often report sexual racism from white LGBT men. The gay Asian-Canadian author Richard Fung has written that while black men are portrayed as hypersexualized, gay Asian men are portrayed as being undersexed.[42] Fung also wrote about feminizing depictions of Asian men in gay pornography, which often focuses on gay Asian men's submission to the pleasure of white men. According to Fung, gay Asian men tend to ignore or display displeasure with races such as Arabs, blacks, and other Asians but seemingly give sexual acceptance and approval to gay white men. White gay men are more frequently than other racial groups state "No Asians" when seeking partners. In interracial gay male pornography, Asian men are usually portrayed as submissive "bottoms".[43]

Fetishisation

As well as race-based sexual rejection, sexual racism also manifests in the form of the hypersexualisation of specific ethnic groups. Within the context of Freudian Sexual Fetishism, people of one race can form sexual fixations towards individuals of a separate generalised racial group. This collective stereotype is established through the perception that an individual’s sexual appeal derives entirely from their race, and is therefore subject to the prejudices that follow.

Racial Fetishism as a culture is often perceived, in this context, as an act or belief motivated by sexual racism. The objectification and reductionist perception of different races, for example, East Asian women, or African American men, relies greatly on their portrayal in forms of media that depict them as sexual objects. An example of such a medium includes Pornography. An instance of this hypersexualisation is commented upon in Artist and Designer Donna Choi’s illustrative series targeting the specific fetishisation of Asian women, named, Does Your Man Suffer From Yellow Fever? (2013). In said illustration, Choi uses satire to depict a white man’s harmful perception of a "china doll stereotype" towards Asian woman and how she is an object to his desires. Choi’s intention comes across through implying the presence of an obvious dehumanisation of Asian women in the eyes of another race. This is a deliberate commentary on the fetishisation rooted within the social issue of Sexual Racism.

The effects of Racial Fetishism as a form of Sexual Racism, is discussed in research conducted by Plummer.[44] Plummer used qualitative interviews within given focus groups, and found that specific social locations came up as areas in which sexual racism commonly manifest. These mentioned social locations included pornographic media, gay clubs and bars, casual sex encounters as well as romantic relationships. This high prevalence was recorded within Plummer’s research to be consequentially related to the recorded lower self-esteem, internalised sexual racism, and increased psychological distress in participants of colour. People subject to this form of racial discernment are targeted in a manner well put by Hook.[45] Hook's historical overview of J.M. Coetzee's novel, largely addressed Coetzee's depictions of racial otherness within South Africa. Additionally, Coetzee goes on to write about how the otherness and social detachment from the colonials was what fabricated present racial stereotypes. Such stereotypes are what is said to encourage the perception of other racial groups as fantasmatic objects; a degrading and generalising view of different racial populations.

See also

- Racial Fetishism

- Racism in the United States

- Interracial Marriage

- Interracial Marriage in the United States

- Online Dating Services

References

- ↑ Stember, Charles Herbert (1976). Sexual Racism: The Emotional Barrier to an Integrated Society. New York: Elsevier. Cited in Marubbio 2006, p. 134.

- ↑ Callander, D., Newman, C. E., & Holt, M. (2015). Is sexual racism really racism? Distinguishing attitudes toward sexual racism and generic racism among gay and bisexual men. Archives of sexual behavior, 44(7), 1991-2000.

- ↑ Carroll, J. (2007, August 16). Most Americans approve of interracial marriages. Retrieved from http:// www.gallup.com/poll/28417/most-americansapprove-interracial-marriages.aspx

- ↑ Yancey, G. (2007). "Experiencing Racism: Differences in the Experiences of Whites Married to Blacks and Non-Black Racial Minorities". Journal of Comparative Family Studies. University of Calgary: Social Sciences. 38 (2): 197–213.

- ↑ De Montesquieu, C. (1989). Montesquieu: The Spirit of the Laws. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ West, C. M. (1995). Mammy, Sapphire, and Jezebel: Historical images of Black women and their implications for psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 32(3), 458.

- ↑ White, D. B. (1999). Ar'n't I a Woman. W.W. Norton & Company.

- ↑ Foner, E. and Mahoney O. (2003). America’s Reconstruction: People and Politics After the Civil War.

- ↑ Kousser, J. M. (2003). Jim Crow Laws. Dictionary of American History, 4, 479-480.

- ↑ Wade, W. C. (1998). The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America. Oxford University Press, USA.

- ↑ Whitfield, S. J. (1991). A death in the delta: The story of Emmett Till. JHU Press.

- ↑ Mendelsohn, G. A., Taylor, L. S., Fiore, A. T. & Cheshire, C. (2014). Black/White Dating Online: Interracial Courtship in the 21st Century. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 3, 2-18.

- ↑ Moran, R. F. (2007). Loving and the Legacy of Unintended Consequences. Wis. L. Rev, 239, 240-281.

- ↑ Parsons, N. (1993). The impact of Seretse Khama on British public opinion 1948-56 and 1978. Historical Studies in Ethnicity, Migration and Diaspora, 12, 195-219.

- ↑ Werner, D. & Mahler, H. (2014). Primary health care: The Return of Health for All. World Nutrition, 5(4), 336-365.

- ↑ Sankin, Aaron (January 18, 2015). "The Weird Racial Politics of Online Dating". The Kernel. The Daily Dot. Retrieved April 18, 2016.

- ↑ Allen, Samantha (September 9, 2015). "'No Blacks' Is Not a Sexual Preference. It's Racism". The Daily Beast. Retrieved April 18, 2016.

- ↑ Mosbergen, Dominique (April 15, 2016). "Online Dating Is Rife With Sexual Racism, 'The Daily Show' Discovers". The Huffington Post. Retrieved April 18, 2016.

- ↑ Tuyau, Maxine (September 15, 2015). "Why Race is Not a Sexual Preference". Daily Life. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ↑ Bradley, Laura (April 13, 2016). "The Daily Show's Jessica Williams and Ronny Chieng Team Up to Prove That Yes, Sexual Racism Is Real". Slate. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ↑ Rosenfeld, M. J. & Thomas, R. J. (2012). Searching for a Mate: The Rise of the Internet as a Social Intermediary. American Sociological Review, 77(4), 523-547.

- 1 2 Template:Hitsch, G. J., Hortacsu, A. & Ariely, D. (2006). What makes you click? Mate preferences and matching outcomes in online dating. MIT Sloan Research Paper No. 4603-06.

- ↑ Schuman, H., Steeh, C., Bobo, L & Krysan, M. (1997). Racial Attitudes in America: Trends and Interpretations (revised edition): Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Ludwig, J. (2004). Acceptance of interracial marriage at record high. Retrieved from http://www.gallup.com/poll/11836/acceptance-interracial-marriage-record-high.aspx, 23.11.2016, 20:00pm.

- ↑ Qian, Z., & Lichter, D. L. (2007). Social boundaries and marital assimilation: Interpreting trends in racial and ethnic intermarriage. American Sociological Review, 72, 68-94.

- 1 2 3 Template:Yancey, G. (2009). Cross-racial differences in the racial preferences of potential dating partners: A test of the alienation of African Americans and Social Dominance Orientation. The Sociology Quarterly, 50, 121-143.

- 1 2 3 4 Template:Robnett, B., & Feliciano, C. (2011). Patterns of racial-ethnic exclusion by internet daters. Social Forces, 89, 807-828.

- ↑ Yancey, G. (2003). Who Is White? Latinos, Asians, And the New Black/nonblack Divide: Lynne Rienner Pub.

- ↑ Fisman, R., Sheena S. I., Emir K. & Itamar S. (2006). "Gender differences in mate selection: Evidence from a speed dating experiment." Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121, 673-697.

- ↑ Spell, S. A. (2016). Not just black and white: how race/ethnicity and gender intersect in hookup culture. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 1-16.

- ↑ Kim, E. (1986). "Asian Americans and American Popular Culture." P. 99-114 in Asian American History Dictionary, edited by R. H. Kim. New York: Greenwood Press.

- ↑ Espiritu, Y. L. (1997). Asian American women and men: labor, laws and love. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

- ↑ Chen, A. S. (1999). "Lives at the centre of the periphery, lives at the periphery of the centre - Chinese American masculinities and bargaining with hegemony." Gender & Society, 13, 584-607.

- ↑ Barringer, H. R., Takeuchi, D. T. & Xenos, P. (1990). "Education, Occupational Prestige, and Income of Asian Americans." Sociology of Education, 63, 27-43.

- ↑ Massey, D. S. & Denton, N. A. (1992). "Residential Segregation of Asian-Origin Groups in United-States Metropolitan Areas." Sociology and Social Research, 76, 170-177.

- ↑ Bobo, L. D. & Massagli, M. P. (2001). "Stereotyping and Urban Inequality." P. 89-162 in Urban Inequality, edited by a M. P. M. Lawrence D. Bobo. New York: Russell Sage.

- ↑ Bordo, S. (1993). Unbearable weight. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ↑ Collins, P. H. (2005). Black Sexual Politics: African Americans, Gender, and the New Racism. New York: Routledge.

- ↑ Potârcă, G & Mills, M. (2015). Racial preferences in online dating across European countries. European Sociological Review, 31(3), 326-341.

- 1 2 Template:Perry, S. L. (2014). Religious Socialisation and Interracial Dating: The effects of childhood religious salience, practice, and parents’ tradition. Journal of Family Issues, 1-25.

- ↑ Nguyen 2014.

- ↑ Gross & Woods 1999, pp. 235–253.

- ↑ Nguyen 2004, pp. 223–228.

- ↑ Plummer, M. D. (2008). Sexual racism in gay communities: Negotiating the ethnosexual marketplace.

- ↑ Hook, D. (2005). The racial stereotype, colonial discourse, fetishism, and racism. Psychoanalytic Review, 92(5), 702-734.

Bibliography

- Gross, Larry P.; Woods, James D., eds. (1999). The Columbia Reader on Lesbians and Gay Men in Media, Society, and Politics. Between Men—Between Women. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10446-3.

- Marubbio, M. Elise (2006). Killing the Indian Maiden: Images of Native American Women in Film. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2414-8.

- Nguyen, Hoang Tan (2004). "The Resurrection of Brandon Lee: The Making of a Gay Asian American Porn Star". In Williams, Linda. Porn Studies. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. pp. 223–270. ISBN 978-0-8223-3300-5.

- ⸻ (2014). A View from the Bottom: Asian American Masculinity and Sexual Representation. Perverse Modernities. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-5684-4.

Further reading

- Kudler, Benjamin A. (2007). Confronting Race and Racism: Social Identity in African American Gay Men (MSW thesis). Northampton, Massachusetts: Smith College. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- Lay, Kenneth James (1993). "Sexual Racism: A Legacy of Slavery". National Black Law Journal. 13 (1): 165–183. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- Lilly, J. Robert; Thomson, J. Michael (1997). "Executing US Soldiers in England, World War II: Command Influence and Sexual Racism". The British Journal of Criminology. 37 (2): 262–288. JSTOR 23638647.

- Plummer, Mary Dianne (2007). Sexual Racism in Gay Communities: Negotiating the Ethnosexual Marketplace (PhD thesis). Seattle: University of Washington. hdl:1773/9181.

- Stevenson, Howard C, Jr. (1994). "The Psychology of Sexual Racism and AIDS: An Ongoing Saga of Distrust and the 'Sexual Other'". Journal of Black Studies. 25 (1): 62–80. doi:10.1177/002193479402500104. ISSN 0021-9347. JSTOR 2784414.