Shape of the universe

| Part of a series on | |||

| Physical cosmology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

|

Early universe

|

|||

|

Components · Structure |

|||

| |||

The shape of the universe is the local and global geometry of the Universe, in terms of both curvature and topology (though, strictly speaking, the concept goes beyond both). The shape of the universe is related to general relativity which describes how spacetime is curved and bent by mass and energy.

There is a distinction between the observable universe and the global universe. The observable universe consists of the part of the universe that can, in principle, be observed due to the finite speed of light and the age of the universe. The observable universe is understood as a sphere around the Earth with a diameter of 93 billion light-years (8.8×1026 m) and would be similar at any observing point (assuming the universe is indeed isotropic, as it appears to be from our vantage point).

According to the book Our Mathematical Universe, the shape of the global universe can be explained with three categories:[1]

- Finite or infinite

- Flat (no curvature), open (negative curvature) or closed (positive curvature)

- Connectivity, how the universe is put together, i.e., simply connected space or multiply connected.

There are certain logical connections among these properties. For example, a universe with positive curvature is necessarily finite.[2] Although it is usually assumed in the literature that a flat or negatively curved universe is infinite, this need not be the case if the topology is not the trivial one.[2]

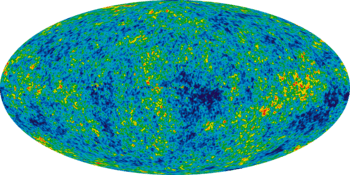

The exact shape is still a matter of debate in physical cosmology, but experimental data from various, independent sources (WMAP, BOOMERanG and Planck for example) confirm that the observable universe is flat with only a 0.4% margin of error.[3][4][5] Theorists have been trying to construct a formal mathematical model of the shape of the universe. In formal terms, this is a 3-manifold model corresponding to the spatial section (in comoving coordinates) of the 4-dimensional space-time of the universe. The model most theorists currently use is the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) model. Arguments have been put forward that the observational data best fit with the conclusion that the shape of the global universe is infinite and flat,[6] but the data are also consistent with other possible shapes, such as the so-called Poincaré dodecahedral space[7][8] and the Picard horn.[9]

Shape of the Observable Universe

As stated in the introduction, there are two aspects to consider:

- its local geometry, which predominantly concerns the curvature of the universe, particularly the observable universe, and

- its global geometry, which concerns the topology of the universe as a whole.

The observable universe can be thought of as a sphere that extends outwards from any observation point for 46.5 billion light years, going farther back in time and more redshifted the more distant away one looks. Ideally, one can continue to look back all the way to the Big Bang; in practice, however, the farthest away one can look is the cosmic microwave background (CMB), as anything past that was opaque. Experimental investigations show that the observable universe is very close to isotropic and homogeneous.

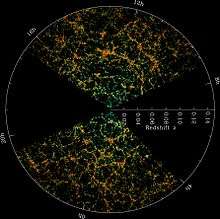

If the observable universe encompasses the entire universe, we may be able to determine the global structure of the entire universe by observation. However, if the observable universe is smaller than the entire universe, our observations will be limited to only a part of the whole, and we may not be able to determine its global geometry through measurement. From experiments, it is possible to construct different mathematical models of the global geometry of the entire universe all of which are consistent with current observational data and so it is currently unknown whether the observable universe is identical to the global universe or it is instead many orders of magnitude smaller than it. The universe may be small in some dimensions and not in others (analogous to the way a cuboid is longer in the dimension of length than it is in the dimensions of width and depth). To test whether a given mathematical model describes the universe accurately, scientists look for the model's novel implications—what are some phenomena in the universe that we have not yet observed, but that must exist if the model is correct—and they devise experiments to test whether those phenomena occur or not. For example, if the universe is a small closed loop, one would expect to see multiple images of an object in the sky, although not necessarily images of the same age.

Cosmologists normally work with a given space-like slice of spacetime called the comoving coordinates, the existence of a preferred set of which is possible and widely accepted in present-day physical cosmology. The section of spacetime that can be observed is the backward light cone (all points within the cosmic light horizon, given time to reach a given observer), while the related term Hubble volume can be used to describe either the past light cone or comoving space up to the surface of last scattering. To speak of "the shape of the universe (at a point in time)" is ontologically naive from the point of view of special relativity alone: due to the relativity of simultaneity we cannot speak of different points in space as being "at the same point in time" nor, therefore, of "the shape of the universe at a point in time".

Curvature of Universe

The curvature of space is a mathematical description of whether or not the Pythagorean theorem is valid for spatial coordinates. There are three possible curvatures the universe can have.

- Flat (A drawn triangle's angles add up to 180°)

- Positively curved (A drawn triangle's angles add up to more than 180°)

- Negatively curved (A drawn triangle's angles add up to less than 180°)

An example of a flat curvature would be any Euclidean geometry, e.g., a triangle drawn on a flat piece of paper.

Curved geometries are in the domain of Non-Euclidean geometry. An example of a positively curved surface would be the surface of a sphere such as the Earth. A triangle drawn from the equator to a pole will result in at least two angles being 90°, making the sum of the 3 angles greater than 180°. An example of a negative curved surface would be the shape of a saddle or mountain pass. A triangle drawn on a saddle shape will result in the sum of the angles adding up to less than 180° due to the curving away as the triangle moves away from the center.

From top to bottom: a spherical universe with Ω > 1, a hyperbolic universe with Ω < 1, and a flat universe with Ω = 1. Note that these depictions of two-dimensional surfaces are merely easily visualizable analogs to the 3-dimensional structure of (local) space.

General relativity explains that mass and energy bend the curvature of spacetime and is used to determine what curvature the universe has by using a value called the density parameter, represented with Omega (Ω). The density parameter is the average density of the universe divided by the critical energy density, that is, the mass energy needed for a universe to be flat. Put another way

- If Ω = 1, the universe is flat

- If Ω > 1, there is positive curvature

- if Ω < 1 there is negative curvature

The geometry of the universe is usually represented in the system of comoving coordinates, according to which the expansion of the universe can be ignored. Comoving coordinates form a single frame of reference according to which the universe has a static geometry of three spatial dimensions.

Under the assumption that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic, the curvature of the observable universe, or the local geometry, is described by one of the three "primitive" geometries (in mathematics these are called the model geometries):

- 3-dimensional Flat Euclidean geometry, generally notated as E3

- 3-dimensional spherical geometry with a small curvature, often notated as S3

- 3-dimensional hyperbolic geometry with a small curvature

One can experimentally calculate this Ω to determine the curvature two ways. One is to count up all the mass-energy in the universe and take its average density then divide that average by the critical energy density. Data from Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) as well as the Planck spacecraft give values for the three constituents of all the mass-energy in the universe - normal mass (baryonic matter and dark matter), relativistic particles (photon and neutrinos) and dark energy or the cosmological constant:[10][11]

Ωmass ≈ 0.315±0.018

Ωrelativistic ≈ 9.24×10−5

ΩΛ ≈ 0.6817±0.0018

Ωtotal = Ωmass + Ωrelativistic + ΩΛ = 1.00±0.02

The actual value for critical density value is measured as ρcritical = 9.47×10−27 kg m−3. From these values, it seems that within experimental error, the universe seems to be flat.

Another way to measure Ω is to do so geometrically by measuring an angle across the observable universe. We can do this by using the CMB and measuring the power spectrum and temperature anisotropy. For an intuition, one can imagine finding a gas cloud that is not in thermal equilibrium due to being so large that light speed cannot propagate the information of the thermal information. Knowing this propagation speed, we then know the size of the gas cloud as well as the distance to the gas cloud, we then have two sides of a triangle and can then determine the angles. Using a method similar to this, the BOOMERanG experiment has determined that the sum of the angles to 180° within experimental error, corresponding to an Ωtotal ≈ 1.00±0.12.[12]

These and other astronomical measurements constrain the spatial curvature to be very close to zero, although they do not constrain its sign. This means that although the local geometries of spacetime are generated by the theory of relativity based on spacetime intervals, we can approximate 3-space by the familiar Euclidean geometry.

The Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) model using Friedmann equations is commonly used to model the universe. The FLRW model provides a curvature of the universe based on the mathematics of fluid dynamics, that is, modeling the matter within the universe as a perfect fluid. Although stars and structures of mass can be introduced into an "almost FLRW" model, a strictly FLRW model is used to approximate the local geometry of the observable universe. Another way of saying this is that if all forms of dark energy are ignored, then the curvature of the universe can be determined by measuring the average density of matter within it, assuming that all matter is evenly distributed (rather than the distortions caused by 'dense' objects such as galaxies). This assumption is justified by the observations that, while the universe is "weakly" inhomogeneous and anisotropic (see the large-scale structure of the cosmos), it is on average homogeneous and isotropic.

Global Universe Structure

Global structure covers the geometry and the topology of the whole universe—both the observable universe and beyond. While the local geometry does not determine the global geometry completely, it does limit the possibilities, particularly a geometry of a constant curvature. The universe is often taken to be a geodesic manifold, free of topological defects; relaxing either of these complicates the analysis considerably. A global geometry is a local geometry plus a topology. It follows that a topology alone does not give a global geometry: for instance, Euclidean 3-space and hyperbolic 3-space have the same topology but different global geometries.

As stated in the introduction, investigations within the study of the global structure of the universe include:

- Whether the universe is infinite or finite in extent

- Whether the geometry of the global universe is flat, positively curved, or negatively curved

- Whether the topology is simply connected like a sphere or multiply connected, like a torus[13]

Infinite or finite

One of the presently unanswered questions about the universe is whether it is infinite or finite in extent. For intuition, it can be understood that a finite universe has a finite volume that, for example, could be in theory filled up with a finite amount of material, while an infinite universe is unbounded and no numerical volume could possibly fill it. Mathematically, the question of whether the universe is infinite or finite is referred to as boundedness. An infinite universe (unbounded metric space) means that there are points arbitrarily far apart: for any distance d, there are points that are of a distance at least d apart. A finite universe is a bounded metric space, where there is some distance d such that all points are within distance d of each other. The smallest such d is called the diameter of the universe, in which case the universe has a well-defined "volume" or "scale."

Bounded and Unbounded

Assuming a finite universe, the universe can either have an edge or no edge. Many finite mathematical spaces, e.g., a disc, have an edge or boundary. Spaces that have an edge are difficult to treat, both conceptually and mathematically. Namely, it is very difficult to state what would happen at the edge of such a universe. For this reason, spaces that have an edge are typically excluded from consideration.

However, there exist many finite spaces, such as the 3-sphere and 3-torus, which have no edges. Mathematically, these spaces are referred to as being compact without boundary. The term compact basically means that it is finite in extent ("bounded") and is a closed set. The term "without boundary" means that the space has no edges. Moreover, so that calculus can be applied, the universe is typically assumed to be a differentiable manifold. A mathematical object that possesses all these properties, compact without boundary and differentiable, is termed a closed manifold. The 3-sphere and 3-torus are both closed manifolds.

An infinite universe (or infinite in a specific spatial direction) must be unbounded in that direction.

Curvature

The curvature of the universe places constraints on the topology. If the spatial geometry is spherical, i.e., possess positive curvature, the topology is compact. For a flat (zero curvature) or a hyperbolic (negative curvature) spatial geometry, the topology can be either compact or infinite.[14] It's very important to note that many textbooks erroneously state that a flat universe implies an infinite universe; however, the correct statement is that a flat universe that is also simply connected implies an infinite universe.[14] For example, Euclidean space is flat, simply connected and infinite, but the torus is flat, multiply connected, finite and compact.

In general, local to global theorems in Riemannian geometry relate the local geometry to the global geometry. If the local geometry has constant curvature, the global geometry is very constrained, as described in Thurston geometries.

The latest research shows that even the most powerful future experiments (like SKA, Planck..) will not be able to distinguish between flat, open and closed universe if the true value of cosmological curvature parameter is smaller than 10−4. If the true value of the cosmological curvature parameter is larger than 10−3 we will be able to distinguish between these three models even now.[15]

Results of the Planck mission released in 2015 show the cosmological curvature parameter, ΩK, to be 0.000±0.005, consistent with a flat universe.[16]

Universe with zero curvature

In a universe with zero curvature, the local geometry is flat. The most obvious global structure is that of Euclidean space, which is infinite in extent. Flat universes that are finite in extent include the torus and Klein bottle. Moreover, in three dimensions, there are 10 finite closed flat 3-manifolds, of which 6 are orientable and 4 are non-orientable. These are the Bieberbach manifolds. The most familiar is the aforementioned 3-Torus universe.

In the absence of dark energy, a flat universe expands forever but at a continually decelerating rate, with expansion asymptotically approaching zero. With dark energy, the expansion rate of the universe initially slows down, due to the effect of gravity, but eventually increases. The ultimate fate of the universe is the same as that of an open universe.

A flat universe can have zero total energy.

Universe with positive curvature

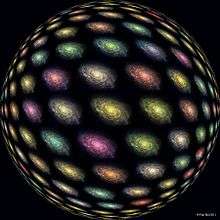

A positively curved universe is described by spherical geometry, and can be thought of as a three-dimensional hypersphere, or some other spherical 3-manifold (such as the Poincaré dodecahedral space), all of which are quotients of the 3-sphere.

Poincaré dodecahedral space, a positively curved space, colloquially described as "soccerball-shaped", as it is the quotient of the 3-sphere by the binary icosahedral group, which is very close to icosahedral symmetry, the symmetry of a soccer ball. This was proposed by Jean-Pierre Luminet and colleagues in 2003[7][17] and an optimal orientation on the sky for the model was estimated in 2008.[8]

Universe with negative curvature

A hyperbolic universe, one of a negative spatial curvature, is described by hyperbolic geometry, and can be thought of locally as a three-dimensional analog of an infinitely extended saddle shape. There are a great variety of hyperbolic 3-manifolds, and their classification is not completely understood. Those of finite volume can be understood via the Mostow rigidity theorem. For hyperbolic local geometry, many of the possible three-dimensional spaces are informally called horn topologies, so called because of the shape of the pseudosphere, a canonical model of hyperbolic geometry. An example is the Picard horn, a negatively curved space, colloquially described as "funnel-shaped".[9]

Curvature: Open or closed

When cosmologists speak of the universe as being "open" or "closed", they most commonly are referring to whether the curvature is negative or positive. These meanings of open and closed are different from the mathematical meaning of open and closed used for sets in topological spaces and for the mathematical meaning of open and closed manifolds, which gives rise to ambiguity and confusion. In mathematics, there are definitions for a closed manifold (i.e., compact without boundary) and open manifold (i.e., one that is not compact and without boundary). A "closed universe" is necessarily a closed manifold. An "open universe" can be either a closed or open manifold. For example, in the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) model the universe is considered to be without boundaries, in which case "compact universe" could describe a universe that is a closed manifold.

Milne model ("spherical" expanding)

If one applies Minkowski space-based Special Relativity to expansion of the universe, without resorting to the concept of a curved spacetime, then one obtains the Milne model. Any spatial section of the universe of a constant age (the proper time elapsed from the Big Bang) will have a negative curvature; this is merely a pseudo-Euclidean geometric fact analogous to one that concentric spheres in the flat Euclidean space are nevertheless curved. Spatial geometry of this model is an unbounded hyperbolic space. The entire universe is contained within a light cone, namely the future cone of the Big Bang. For any given moment t > 0 of coordinate time (assuming the Big Bang has t = 0), the entire universe is bounded by a sphere of radius exactly c t. The apparent paradox of an infinite universe contained within a sphere is explained with length contraction: the galaxies farther away, which are travelling away from the observer the fastest, will appear thinner.

This model is essentially a degenerate FLRW for Ω = 0. It is incompatible with observations that definitely rule out such a large negative spatial curvature. However, as a background in which gravitational fields (or gravitons) can operate, due to diffeomorphism invariance, the space on the macroscopic scale, is equivalent to any other (open) solution of Einstein's field equations.

See also

- De Sitter space

- Ekpyrotic universe − a String theory-related model depicting a five-dimensional, membrane-shaped universe; an alternative to the Hot Big Bang Model, whereby the universe is described to have originated when two membranes collided at the fifth dimension

- Extra dimensions in String Theory for 6 or 7 extra space-like dimensions all with a compact topology.

- History of the Center of the Universe

- Holographic Universe

- List of Cosmology paradoxes

- Theorema Egregium − The "remarkable theorem" discovered by Gauss which showed there is an intrinsic notion of curvature for surfaces. This is used by Riemann to generalize the (intrinsic) notion of curvature to higher-dimensional spaces

- Three-torus model of the universe

- Zero-energy universe

References

- ↑ Tegmark, Max (2014). Our Mathematical Universe: My Quest for the Ultimate Nature of Reality (1 ed.). Knopf. ISBN 978-0307599803.

- 1 2 G. F. R. Ellis; H. van Elst (1999). "Cosmological models (Cargèse lectures 1998)". In Marc Lachièze-Rey. Theoretical and Observational Cosmology. NATO Science Series C. 541. p. 22. arXiv:gr-qc/9812046

. Bibcode:1999toc..conf....1E. ISBN 978-0792359463.

. Bibcode:1999toc..conf....1E. ISBN 978-0792359463. - ↑ "Will the Universe expand forever?". NASA. 24 January 2014. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ "Our universe is Flat". FermiLab/SLAC. 7 April 2015.

- ↑ Marcus Y. Yoo (2011). "Unexpected connections". Engineering & Science. Caltech. LXXIV1: 30.

- ↑ Demianski, Marek; Sánchez, Norma; Parijskij, Yuri N. (2003). "Topology of the universe and the cosmic microwave background radiation". The Early Universe and the Cosmic Microwave Background: Theory and Observations. Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Study Institute. The early universe and the cosmic microwave background: theory and observations. Springer. 130: 161. Bibcode:2003eucm.book..159D. ISBN 1-4020-1800-2.

- 1 2 Luminet, Jean-Pierre; Weeks, Jeff; Riazuelo, Alain; Lehoucq, Roland; Uzan, Jean-Phillipe (2003-10-09). "Dodecahedral space topology as an explanation for weak wide-angle temperature correlations in the cosmic microwave background". Nature. 425 (6958): 593–5. arXiv:astro-ph/0310253

. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..593L. doi:10.1038/nature01944. PMID 14534579.

. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..593L. doi:10.1038/nature01944. PMID 14534579. - 1 2 Roukema, Boudewijn; Zbigniew Buliński; Agnieszka Szaniewska; Nicolas E. Gaudin (2008). "A test of the Poincare dodecahedral space topology hypothesis with the WMAP CMB data". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 482 (3): 747. arXiv:0801.0006

. Bibcode:2008A&A...482..747L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078777.

. Bibcode:2008A&A...482..747L. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078777. - 1 2 Aurich, Ralf; Lustig, S.; Steiner, F.; Then, H. (2004). "Hyperbolic Universes with a Horned Topology and the CMB Anisotropy". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 21 (21): 4901–4926. arXiv:astro-ph/0403597

. Bibcode:2004CQGra..21.4901A. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/21/21/010.

. Bibcode:2004CQGra..21.4901A. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/21/21/010. - ↑ "Density Parameter, Omega". hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. Retrieved 2015-06-01.

- ↑ Ade, P. A. R.; Aghanim, N.; Armitage-Caplan, C.; Arnaud, M.; Ashdown, M.; Atrio-Barandela, F.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Banday, A. J.; Barreiro, R. B.; Bartlett, J. G.; Battaner, E.; Benabed, K.; Benoît, A.; Benoit-Lévy, A.; Bernard, J.-P.; Bersanelli, M.; Bielewicz, P.; Bobin, J.; Bock, J. J.; Bonaldi, A.; Bond, J. R.; Borrill, J.; Bouchet, F. R.; Bridges, M.; Bucher, M.; Burigana, C.; Butler, R. C.; Calabrese, E.; et al. (2014). "Planck2013 results. XVI. Cosmological parameters". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 571: A16. arXiv:1303.5076

. Bibcode:2014A&A...571A..16P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321591.

. Bibcode:2014A&A...571A..16P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201321591. - ↑ De Bernardis, P.; Ade, P. A. R.; Bock, J. J.; Bond, J. R.; Borrill, J.; Boscaleri, A.; Coble, K.; Crill, B. P.; De Gasperis, G.; Farese, P. C.; Ferreira, P. G.; Ganga, K.; Giacometti, M.; Hivon, E.; Hristov, V. V.; Iacoangeli, A.; Jaffe, A. H.; Lange, A. E.; Martinis, L.; Masi, S.; Mason, P. V.; Mauskopf, P. D.; Melchiorri, A.; Miglio, L.; Montroy, T.; Netterfield, C. B.; Pascale, E.; Piacentini, F.; Pogosyan, D.; et al. (2000). "A flat Universe from high-resolution maps of the cosmic microwave background radiation". Nature. 404 (6781): 955–9. arXiv:astro-ph/0004404

. Bibcode:2000Natur.404..955D. doi:10.1038/35010035. PMID 10801117.

. Bibcode:2000Natur.404..955D. doi:10.1038/35010035. PMID 10801117. - ↑ P.C.W.Davies (1977). Space and time in the modern universe. cambridge university press. ISBN 0-521-29151-8.

- 1 2 Luminet, Jean-Pierre; Lachièze-Rey, Marc (1995). "Cosmic Topology". Physics Reports. 254 (3): 135–214. arXiv:gr-qc/9605010

. Bibcode:1995PhR...254..135L. doi:10.1016/0370-1573(94)00085-h.

. Bibcode:1995PhR...254..135L. doi:10.1016/0370-1573(94)00085-h. - ↑ Vardanyan, Mihran; Trotta, Roberto; Silk, Joseph (2009). "How flat can you get? A model comparison perspective on the curvature of the Universe". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 397: 431. arXiv:0901.3354

. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.397..431V. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.14938.x.

. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.397..431V. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.14938.x. - ↑ Planck Collaboration; Ade, P. A. R.; Aghanim, N.; Arnaud, M.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Banday, A. J.; Barreiro, R. B.; Bartlett, J. G.; Bartolo, N.; Battaner, E.; Battye, R.; Benabed, K.; Benoit, A.; Benoit-Levy, A.; Bernard, J.-P.; Bersanelli, M.; Bielewicz, P.; Bonaldi, A.; Bonavera, L.; Bond, J. R.; Borrill, J.; Bouchet, F. R.; Boulanger, F.; Bucher, M.; Burigana, C.; Butler, R. C.; Calabrese, E.; et al. (2015). "Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters". arXiv:1502.01589

[astro-ph.CO].

[astro-ph.CO]. - ↑ "Is the universe a dodecahedron?", article at PhysicsWeb.

External links

- How do we know that the universe is flat A video explains how astrophysicists measure the geometry of the universe at Physicsworld.com

- Geometry of the Universe at icosmos.co.uk

- Janna Levin, Evan Scannapieco & Joseph Silk (1998). "The topology of the universe: the biggest manifold of them all". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 15 (9). arXiv:gr-qc/9803026

. Bibcode:1998CQGra..15.2689L. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/15/9/015.

. Bibcode:1998CQGra..15.2689L. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/15/9/015. - Lachièze-Rey, M., Luminet, J.P. (1995). "Cosmic Topology". Physics Reports. 254 (3): 135–214. arXiv:gr-qc/9605010

. Bibcode:1995PhR...254..135L. doi:10.1016/0370-1573(94)00085-H.

. Bibcode:1995PhR...254..135L. doi:10.1016/0370-1573(94)00085-H. - Universe is Finite, "Soccer Ball"-Shaped, Study Hints. Possible wrap-around dodecahedral shape of the universe

- Classification of possible universes in the Lambda-CDM model.

- Fagundes, Helio V. (2002). "Exploring the global topology of the universe". Brazilian Journal of Physics. 32 (4). doi:10.1590/S0103-97332002000500012.

- Grime, James. "π39 (Pi and the size of the Universe)". Numberphile. Brady Haran.

- What do you mean the universe is flat? Scientific American Blog explanation of a flat universe and the curved spacetime in the universe.