Hanfu

| Hanfu | |||||||||||||||

|

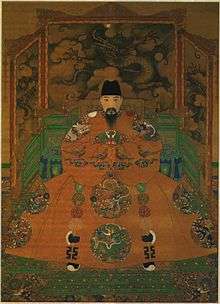

The mianfu of Emperor Wu of Jin Dynasty, 7th-century painting by court artist Yan Liben | |||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉服 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 漢服 | ||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin |

| ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Han clothing | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Hanfu (simplified Chinese: 汉服; traditional Chinese: 漢服; pinyin: ![]() Hànfú; literally: "Han clothing") is the historical dress of the Han Chinese people.[1]

Hànfú; literally: "Han clothing") is the historical dress of the Han Chinese people.[1]

The term Hanfu was originally recorded by the Book of Han, which refers to Han dynasty's traditional dresses: "then many came to the Court to pay homage and were delighted at the clothing style of [the] Han [dynasty]."[2]

History

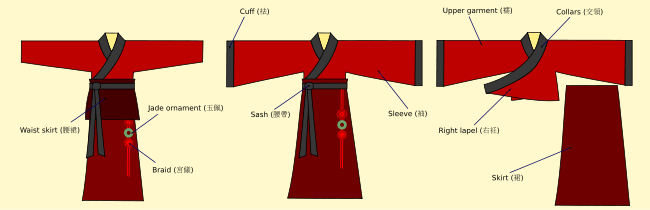

From the beginning of its history, Hanfu (especially in elite circles) was inseparable from silk, supposedly discovered by the Yellow Emperor's consort, Leizu. The Shang Dynasty (c. 1600 BC - 1000 BC), developed the rudiments of Hanfu; it consisted of a yi, a narrow-cuffed, knee-length tunic tied with a sash, and a narrow, ankle-length skirt, called chang, worn with a bixi, a length of fabric that reached the knees. Vivid primary colors and green were used, due to the degree of technology at the time.

The dynasty to follow the Shang, the Western Zhou Dynasty, established a strict hierarchical society that used clothing as a status meridian, and inevitably, the height of one’s rank influenced the ornateness of a costume. Such markers included the length of a skirt, the wideness of a sleeve and the degree of ornamentation. In addition to these class-oriented developments, the Hanfu became looser, with the introduction of wide sleeves and jade decorations hung from the sash which served to keep the yi closed. The yi was essentially wrapped over, in a style known as jiaoling youren, or wrapping the right side over before the left, because of the initially greater challenge to the right-handed wearer (people of Zhongyuan discouraged left-handedness like many other historical cultures, considering it unnatural, barbarian, uncivilized and unfortunate).

Several Styles

Garments

The style of historical Han clothing can be summarized as containing garment elements that are arranged in distinctive and sometimes specific ways. This may be different from the traditional garment of other ethnic groups in China, most notably the Manchu-influenced Han clothes, the qipao, which is popularly assumed to be the solely recognizable style of traditional Chinese garb. A comparison of the two styles can be seen as the following provides:

| Component | Han | Manchu |

|---|---|---|

| Upper Garment | Consist of "yi" (衣), which have loose lapels and are open | Consist of "pao" (袍), which have secured lapels around the neck and no front openings |

| Lower Garment | Consist of skirts called "chang" (裳) | Consist of pants or trousers called "ku" (褲) |

| Collars | Generally, diagonally crossing each other, with the left crossing over the right | Parallel vertical collars with parallel diagonal lapels, which overlap |

| Sleeves | Long and loose | Narrow and tight |

| Buttons | Sparingly used and concealed inside the garment | Numerous and prominently displayed |

| Fittings | Belts and sashes are used to close, secure, and fit the garments around the waist | Flat ornate buttoning systems are typically used to secure the collar and fit the garment around the neck and upper torso |

A complete Hanfu garment is assembled from several pieces of clothing into an attire:

- Yi (衣): Any open cross-collar garment, and worn by both sexes

- Pao (袍): Any closed full-body garment, worn only by men in Hanfu

- Ru (襦): Open cross-collar shirt

- Shan (衫): Open cross-collar shirt or jacket that is worn over the yi

- Qun (裙) or chang (裳): Skirt for women and men

- Ku (褲): Trousers or pants

Hats, headwear and hairstyles

On top of the garments, hats (for men) or hairpieces (for women) may be worn. One can often tell the profession or social rank of someone by what they wear on their heads. The typical types of male headwear are called jin (巾) for soft caps, mao (帽) for stiff hats and guan (冠) for formal headdress. Officials and academics have a separate set of hats, typically the putou (幞頭), the wushamao (烏紗帽), the si-fang pingding jin (四方平定巾; or simply, fangjin: 方巾) and the Zhuangzi jin (莊子巾). A typical hairpiece for women is the ji (笄) but there are more elaborate hairpieces.

In addition, managing hair was also a crucial part of ancient Han people's daily life. Commonly, males and females would stop cutting their hair once they reached adulthood. This was marked by the Chinese coming of age ceremony Guan Li, usually performed between ages 15 to 20. They allowed their hair to grow long naturally until death, including facial hair. This was due to Confucius' teaching "身體髮膚,受諸父母,不敢毀傷,孝之始也" - which can be roughly translated as 'My body, hair and skin are given by my father and mother, I dare not damage any of them, as this is the least I can do to honor my parents'. In fact, cutting one's hair off in ancient China was considered a legal punishment called '髡', designed to humiliate criminals, as well as tattooing '黥', since regular people wouldn't have tattoos on their skin due to the same teaching.

Children were exempt from the above commandment, they could cut their hair short, make different kinds of knots or braids, or simply just let them hang without any care. However, once they entered adulthood, every male was obliged to tie his long hair into a topknot called ji (髻) either on or behind his head and always cover the bun up with different kinds of headdresses (except Buddhist monks, who would always keep their heads completely shaved to show that they're "cut off from the earthly bonds of the mortal world"; and Taoist monks, who would usually just use hair sticks called '簪' (zān)to hold the buns in place without concealing them). Thus the 'disheveled hair', a common but erring depiction of ancient Chinese male figures seen in most modern Chinese period dramas or movies with hair (excluding facial hair) hanging down from both sides and/or in the back are historically inaccurate. Females on the other hand, enjoyed more freedom in terms of decorating their hair as adults. They could still arrange their hair into various kinds of hairstyles as they pleased. There were different fashions for women in various dynastic periods, whereas in more than 2,000 years of Han Chinese history males had only one choice: the bun.

Such strict 'no-cutting' hair tradition was implemented all throughout Han Chinese history since Confucius' time up until the end of Ming Dynasty (1644 CE), when the Qing Prince Dorgon forced the male Han people to adopt the hairstyle of Manchu men, which was shave their foreheads bald and gather the rest of the hair into ponytails in the back (See Queue) in order to show that they submitted to Qing authority, the so-called "Queue Order" (薙髮令). Han children and females were spared from this order, also Taoist monks were allowed to keep their hair and Buddhist monks were allowed to keep all their hair shaven. Han defectors to the Qing like Li Chengdong and Liu Liangzuo and their Han troops carried out the queue order to force it on the general population. Han Chinese soldiers in 1645 under Han General Hong Chengchou forced the queue on the people of Jiangnan while Han people were initially paid silver to wear the queue in Fuzhou when it was first implemented.[3]

%2C_Chi-ning_City_(%E6%BF%9F%E5%AF%A7%E5%B8%82).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

_from_Tomb_of_Lou_Jui_(%E5%A9%81%E5%8F%A1).jpg)

| Man's Headwear | view | Woman's Headwear | view |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mianguan |  | Phoenix crown |  |

| Tongtianguan |  | Huasheng | |

| Pibian |  | Bian |  |

| Jinxianguan |  | Hairpin |  |

| Longguan |  | ||

| Putou (襆頭), lit. 'Head Cover' or 'Head Wrap'. An early form of informal headwear dates back as early as Jin Dynasty that later developed into several variations for wear in different occasions. |  | ||

| Zhangokfutou (展角幞頭), lit. 'Spread-Horn Head Cover', designed by the founder of Song Dynasty, with elongated horns on both sides in order to keep the distance between his officials so they couldn't whisper to each other during court assemblies. It was also later adapted by the Ming Dynasty, authorized for court wear. |  | ||

| Zhan Chi Fu Tou (展翅幞頭), lit. 'Spread-Wing Head Cover', more commonly known by its nickname Wu Sha Mao (烏紗帽), lit. 'Black-Cloth Hat', was the standard headwear of officials during the Ming Dynasty. The term 'Wu Sha Mao' is still frequently used in modern Chinese slang when referring to a government position. |  | ||

| Yishanguan (翼善冠), lit. 'Winged Crown of Philanthropy', worn by emperors and princes of the Ming Dynasty, as well as kings of many of its tributaries such as Korea and Ryukyu. The version worn by emperors was elaborately decorated with jewels and dragons; while the others looked basically like Wu Sha Mao only with wings folded upwards. |  | ||

| Pashou |  | ||

| Patou |  | ||

| Zhuzi jin |  | ||

| Zhouzi jin |  | ||

| Zhuangzi jin |  | ||

| Fujin |  | ||

| Li |  | ||

| Zi |  |

Style

Han-Chinese clothing had changed and evolved with the fashion of the days since its commonly assumed beginnings in the Shang dynasty. Many of the earlier designs are more gender-neutral and simple in cuttings. Later garments incorporate multiple pieces with men commonly wearing pants and women commonly wearing skirts. Clothing for women usually accentuates the body's natural curves through wrapping of upper garment lapels or binding with sashes at the waist.

Each dynasty has their own styles of Hanfu as they evolved and only few styles are 'fossilized'.

Informal wear

Types include tops (yi) and bottoms (divided further into pants and skirts for both genders, with terminologies chang or qun), and one-piece robes that wrap around the body once or several times (shenyi).

- Zhongyi (中衣) or zhongdan (中單): inner garments, mostly white cotton or silk

- Shanqun (衫裙): a short coat with a long skirt

- Ruqun (襦裙): a top garment with a separate lower garment or skirt

- Kuzhe (褲褶): a short coat with trousers

- Zhiduo/zhishen (直裰/直身): a Ming Dynasty style robe, similar to a zhiju shenyi but with vents at the side and 'stitched sleeves' (i.e. the sleeve cuff is closed save a small opening for the hand to go through)

- Daopao/Fusha (道袍/彿裟): Taoist/Buddhist priests' full dress ceremonial robes. Note: Daopao doesn't necessarily means Taoist's robe, it actually is a style of robe for scholars. And the Taoist version of Daopao is called De Luo (得罗), and Buddhist version is called Hai Qing (海青).

A typical set of Hanfu can consist of two or three layers. The first layer of clothing is mostly the zhongyi (中衣) which is typically the inner garment much like a Western T-shirt and pants. The next layer is the main layer of clothing which is mostly closed at the front. There can be an optional third layer which is often an overcoat called a zhaoshan which is open at the front. More complicated sets of Hanfu can have many more layers.

For footwear, white socks and black cloth shoes (with white soles) are the norm, but in the past, shoes may have a front face panel attached to the tip of the shoes. Daoists, Buddhists and Confucians may have white stripe chevrons.

Semi-formal wear

A piece of Hanfu can be "made semi-formal" by the addition of the following appropriate items:

- Chang (裳): a pleated skirt

- Bixi (蔽膝): long front cloth panel attached from the waist belt

- Zhaoshan (罩衫): long open fronted coat

- Guan (冠) or any formal hats

Generally, this form of wear is suitable for meeting guests or going to meetings and other special cultural days. This form of dress is often worn by the nobility or the upper-class as they are often expensive pieces of clothing, usually made of silks and damasks. The coat sleeves are often deeper than the shenyi to create a more voluminous appearance.

Formal wear

In addition to informal and semi-formal wear, there is a form of dress that is worn only at confucian rituals (like important sacrifices or religious activities) or by special people who are entitled to wear them (such as officials and emperors). Formal wear are usually long wear with long sleeves except Xuanduan.

Formal garments may include:

- Xuanduan (玄端): a very formal dark robe; equivalent to the Western white tie

- Shenyi (深衣): a long full body garment

- Quju (曲裾): diagonal body wrapping

- Zhiju (直裾): straight lapels

- Yuanlingshan (圓領衫), lanshan (襴衫) or panlingpao (盤領袍): closed, round-collared robe; mostly used for official or academical dress

| Style | Views | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xuanduan |  |  |  | |

| Shenyi | _por_Ku_K'ai-chih.jpg) | |  | |

| |  |  | ||

| Yuanlingshan |  |  |  |  |

The most formal Hanfu that a civilian can wear is the xuanduan (sometimes called yuanduan 元端[4]), which consists of a black or dark blue top garment that runs to the knees with long sleeve (often with white piping), a bottom red chang, a red bixi (which can have a motif and/or be edged in black), an optional white belt with two white streamers hanging from the side or slightly to the front called peishou (佩綬), and a long black guan. Additionally, wearers may carry a long jade gui (圭) or wooden hu (笏) tablet (used when greeting royalty). This form of dress is mostly used in sacrificial ceremonies such as Ji Tian (祭天) and Ji Zu (祭祖), etc., but is also appropriate for state occasions. The xuanduan is basically a simplified version of full court dress of the officials and the nobility.

Those in the religious orders wear a plain middle layer garment followed by a highly decorated cloak or coat. Taoists have a 'scarlet gown' (絳袍)[5] which is made of a large cloak sewn at the hem to create very long deep sleeves used in very formal rituals. They are often scarlet or crimson in color with wide edging and embroidered with intricate symbols and motifs such as the eight trigrams and the yin and yang Taiji symbol. Buddhist have a cloak with gold lines on a scarlet background creating a brickwork pattern which is wrapped around over the left shoulder and secured at the right side of the body with cords. There may be further decorations, especially for high priests.[6]

Those in academia or officialdom have distinctive gowns (known as changfu 常服 in court dress terms). This varies over the ages but they are typically round collared gowns closed at the front. The most distinct feature is the headwear which has 'wings' attached. Only those who passed the civil examinations are entitled to wear them, but a variation of it can be worn by ordinary scholars and laymen and even for a groom at a wedding (but with no hat).

Court dress

|

Court dress is the dress worn at very formal occasions and ceremonies that are in the presence of a monarch (such as an enthronement ceremony). The entire ensemble of clothing can consist of many complex layers and look very elaborate. Court dress is similar to the xuanduan in components but have additional adornments and elaborate headwear. They are often brightly colored with vermillion and blue. There are various versions of court dress that are worn for certain occasions.

Court dress refers to:

| Romanization | Hanzi | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Mianfu | 冕服 | religious court dress of emperor, officials or nobility |

| Bianfu | 弁服 | ceremonial military dress of emperor, officials or nobility |

| Chaofu | 朝服 | a red ceremonial court dress of emperor, officials or nobility |

| Gongfu | 公服 | formal court dress according to ranks |

| Changfu | 常服 | everyday court dress |

The practical use of court dress is now obsolete in the modern age since there is no reigning monarch in China anymore.

Specific styles

Historically, Hanfu has influenced many of its neighbouring cultural costumes, such as Japanese kimono, yukata,[7][8] and the Vietnamese Áo giao lĩnh.[9][10] Elements of Hanfu have also been influenced by neighbouring cultural costumes, especially by the nomadic peoples to the north, and Central Asian cultures to the west by way of the Silk Road.[11][12]

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty represents a golden age in China's history, where the arts, sciences and economy were thriving. Female dress and personal adornments in particular reflected the new visions of this era, which saw unprecedented trade and interaction with cultures and philosophies alien to Chinese borders. Although it still continues the clothing of its predecessors such as Han and Sui dynasties, fashion during the Tang was also influenced by its cosmopolitan culture and arts. Where previously Chinese women had been restricted by the old Confucian code to closely wrapped, concealing outfits, female dress in the Tang Dynasty gradually became more relaxed, less constricting and even more revealing.[13] The Tang Dynasty also saw the ready acceptance and syncretisation with Chinese practice, of elements of foreign culture by the Han Chinese. The foreign influences prevalent during Tang China included cultures from Gandhara, Turkistan, Persia and Greece. The stylistic influences of these cultures were fused into Tang-style clothing without any one particular culture having especial prominence.[14]

Song and Yuan dynasty

Some features of Tang Clothing carried into the Song Dynasty Such as court customs. Song court customs often use red color for their garments with black leather shoe and hats. Collar edges and sleeve edges of all clothes that have been excavated were decorated with laces or embroidered patterns. Such clothes were decorated with patterns of peony, camellia, plum blossom, and lily, etc. Song Empress often had three to five distinctive jewelry-like marks on their face (two side of the cheek, other two next to the eyebrows and one on the forehead). Although some of Song clothing have similarities with previous dynasties, some unique characteristics separate it from the rest. Many of Song Clothing goes into Yuan and Ming.[15] One of the common clothing style for the woman in Song Dynasty is Beizi(褙子), which were usually regard as shirt or jacket and could be matched with Ru or Ku. There are two size of Beizi: short one is crown rump length and long one means the length cover to knees.[16]

Ming dynasty

Female's Ao Qun (襖裙, lit. coat-and-skirt), historical artifact kept in Kong Family Mansion.

Female's Ao Qun (襖裙, lit. coat-and-skirt), historical artifact kept in Kong Family Mansion. Commoner's clothing

Commoner's clothing Nicolas Trigault, a Flemish Jesuit in Ming style Confucian-scholar costume (Rufu 儒服).

Nicolas Trigault, a Flemish Jesuit in Ming style Confucian-scholar costume (Rufu 儒服).

Drawing by Peter Paul Rubens, 1617. A portrait painting of Nicolas Trigault believed to be wearing the same costume as shown in the drawing. By Rubens' workshop.

A portrait painting of Nicolas Trigault believed to be wearing the same costume as shown in the drawing. By Rubens' workshop.

According to the Veritable Records of Hongwu Emperor (太祖實錄, a detailed official account written by court historians recording the daily activities of Hongwu Emperor during his reign.), shortly after the founding of Ming dynasty, "on the Renzi day in the second month of the first year of Hongwu era (Feb 29th, 1368 CE), Hongwu emperor decreed that all fashions of clothing and headwear shall be restored to the standard of Tang, all citizens shall gather their hairs on top of their heads, and officials shall wear the Wu Sha Mao (Black-cloth Hats), round-collar robes, belts, and black boots." ("洪武元年二月壬子...至是,悉命復衣冠如唐制,士民皆束髮於頂,官則烏紗帽,圓領袍,束帶,黑靴。") This attempt to restore the entire clothing system back to the way it was during Tang Dynasty was a gesture from the founding emperor that signified the restoration of Han tradition and cultural identity after defeating the Yuan dynasty. However, fashionable Mongol attires, items and hats were still sometimes worn by early Ming royalties such as Emperors Hongwu and Zhengde.[12][17]

The Ming dynasty also brought many changes to its clothing, as many dynasties do. They implemented metal buttons and the collar changed from the symmetrical type of the Song Dynasty (960-1279) to the main circular type. Compared with the costume of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), the proportion of the upper outer garment to lower skirt in the Ming Dynasty was significantly inverted. Since the upper outer garment was shorter and the lower garment was longer, the jacket gradually became longer to shorten the length of the exposed skirt. Young ladies in the mid Ming Dynasty usually preferred to dress in these waistcoats. The waistcoats in the Qing Dynasty were transformed from those of the Yuan Dynasty. During the Ming Dynasty, Confucian codes and ideals were popularized and it had a significant effect on clothing.[18]

In Ming Dynasty, both Civil and Military officials were divided into nine Ranks (品), each Rank was further subdivided into Primary (正) and Secondary (從) so there were technically eighteen Ranks, with First Rank Primary (正一品) being the highest and the Ninth Rank Secondary (從九品) the lowest. Officials of the upper four Ranks (from First Rank Primary to Fourth Rank Secondary) were entitled to wear the red robes; mid-Ranks (Fifth Rank Primary to Seventh Rank Secondary) to wear blue robes and the lower Ranks (Eighth Rank Primary to Ninth Rank Secondary) to wear green robes. In addition, each exact Rank was indicated by a picture of unique animal (either real or legendary) sewn on a square-shaped patch in both front and back of the robe, so fellow officials could identify someone's Rank from afar. (Use the chart below for comprehensible facts, for more information see Mandarin square)

| A yapai(牙牌) from Ming Dynasty as mentioned in the painting above, this is the side engraved with instructions: the smaller text on the right reads "Officials who come to pay tribute [to the emperor] shall wear this card, those found without one will be prosecuted by law. Those who borrow or lend this card will be punished equally." the larger text on the left reads "Not required [to be checked] when outside the capital [Beijing]." |

| Official Dress Codes of the Ming Dynasty | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precedence | Rank | Robe Color | Animal on Patch (Civil) | Animal on Patch (Military) | Exemplified Positions (Not All-Inclusive) | ||

| | 正一品 | | | Regional Commander 都督 | |||

| | 從一品 | | | Regional Executive Officer 都督同知 | |||

| | 正二品 | | | Secretary of Defense 兵部尚書 | |||

| | 從二品 | | | Provincial Deputy Commander 都指揮同知 | |||

| | 正三品 | | | Deputy Secretary of Labor 工部侍郎 | |||

| | 從三品 | | | Minister of Salt Supply 都轉鹽運使 | |||

| | 正四品 | | | Minister of Foreign Affairs 鴻臚寺卿 | |||

| | 從四品 | | | Governor's Junior Assistant 參議 | |||

| | 正五品 | | | Grand Secretary of the Cabinet 内閣大學士 | |||

| | 從五品 | | | Deputy Manager of the Department of Justice 刑部員外郎 | |||

| | 正六品 | | | Minister of Buddhist Affairs 僧錄司善世 | |||

| | 從六品 | | | Deputy Manager of Minority Affairs 安撫司副使 | |||

| | 正七品 | | | Investigating Censor 監察御史 | |||

| | 從七品 | | | Deputy Ambassador 行人司左司副 | |||

| | 正八品 | | | Deputy County Administrator 縣丞 | |||

| | 從八品 | | | Supervisor at the Ministry of Royal Food Service 光祿寺監事 | |||

| | 正九品 | | (not seahorse) | Chief Officer at the Headquarter of Official Travels 會同館大使 | |||

| | 從九品 | | | Marshal 巡檢 | |||

Qing dynasty

During the Qing dynasty, Manchu style clothing was only required for scholar-official elite such as the Eight Banners members and Han men serving as government officials. The great majority of Han civilians were allowed to wear Han clothing as they had during the Ming, yet most Han civilian men voluntarily adopted Manchu clothing like Changshan on their own free will. As a result, by the late Qing, not only officials and scholars, but a great many commoners as well, started to wear Manchu attire.[19][20]

Throughout the Qing dynasty Han women continued to wear clothing from Ming dynasty.[21] Neither Taoist priests nor Buddhist monks were required to wear the queue by the Qing; they continued to wear their traditional hairstyles, completely shaved heads for Buddhist monks, and long hair in the traditional Chinese topknot for Taoist priests.[22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33]

It was Han Chinese defectors who carried out massacres against people refusing to wear the queue. Li Chengdong, a Han Chinese general who had served the Ming but defected to the Qing,[34] ordered troops to carry out three separate massacres in the city of Jiading within a month, resulting in tens of thousands of deaths. The third massacre left few survivors.[35] The three massacres at Jiading District are some of the most infamous, with estimated death tolls in the tens or even hundreds of thousands.[36] Jiangyin also held out against about 10,000 Qing troops for 83 days. When the city wall was finally breached on October 9, 1645, the Qing army, led by the Han Chinese Ming defector Liu Liangzuo (劉良佐), who had been ordered to "fill the city with corpses before you sheathe your swords," massacred the entire population, killing between 74,000 and 100,000 people.[37]

Han Chinese soldiers in 1645 under Han General Hong Chengchou forced the queue on the people of Jiangnan while Han people were initially paid silver to wear the queue in Fuzhou when it was first implemented.[3][38]

Han female custom in Qing dynasty (1)

Han female custom in Qing dynasty (1) Han female custom in Qing dynasty (2)

Han female custom in Qing dynasty (2) Children in Qing dynasty

Children in Qing dynasty Taoist Clothing in Qing dynasty

Taoist Clothing in Qing dynasty

Republic of China

During the Republican period in the 1920s qipao dress suddenly became fashionable for women and was widely adopted.

Gallery

Detail of a lacquerware painting from the Ching-mên Tomb (Chinese: 荊門楚墓; pinyin: Jīng mén chǔ mù) of the State of Ch'u (704–223 BC)

Detail of a lacquerware painting from the Ching-mên Tomb (Chinese: 荊門楚墓; pinyin: Jīng mén chǔ mù) of the State of Ch'u (704–223 BC) A female servant and male advisor in Chinese silk robes, ceramic figurines from the Western Han Period (202 BCE – 9 CE)

A female servant and male advisor in Chinese silk robes, ceramic figurines from the Western Han Period (202 BCE – 9 CE)- A Han Dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE) pottery statuette of a female dancer

A Han dynasty fresco of a man in blue hunting dress

A Han dynasty fresco of a man in blue hunting dress A Han dynasty fresco of a horseman in red hunting dress

A Han dynasty fresco of a horseman in red hunting dress A late Western Han (202 BC - 9 AD) painting from a tomb of Dongping County, Shandong province, showing men and women wearing Hanfu

A late Western Han (202 BC - 9 AD) painting from a tomb of Dongping County, Shandong province, showing men and women wearing Hanfu A Western Han (202 BC - 9 AD) fresco depicting Confucius and Laozi, from a tomb of Dongping County, Shandong province, China

A Western Han (202 BC - 9 AD) fresco depicting Confucius and Laozi, from a tomb of Dongping County, Shandong province, China%2C_Tung-p'ing_County_(%E6%9D%B1%E5%B9%B3%E7%B8%A3).jpg) A man dressing in the Han dynasty style Shên-i

A man dressing in the Han dynasty style Shên-i Fresco of a Western Han dynasty woman

Fresco of a Western Han dynasty woman Lively musicians playing a bamboo flute and a plucked instrument, Chinese ceramic statues from the Eastern Han period (25-220 AD), Shanghai Museum

Lively musicians playing a bamboo flute and a plucked instrument, Chinese ceramic statues from the Eastern Han period (25-220 AD), Shanghai Museum A Chinese ceramic statue of a woman holding a bronze mirror, Eastern Han period (25-220 AD), Sichuan Provincial Museum, Chengdu

A Chinese ceramic statue of a woman holding a bronze mirror, Eastern Han period (25-220 AD), Sichuan Provincial Museum, Chengdu Mural from the Dahuting Tomb (Chinese: 打虎亭汉墓, Pinyin: Dahuting Han mu) of the late Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD), located in Zhengzhou, Henan province, China

Mural from the Dahuting Tomb (Chinese: 打虎亭汉墓, Pinyin: Dahuting Han mu) of the late Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD), located in Zhengzhou, Henan province, China Mural from the Dahuting Tomb (Chinese: 打虎亭汉墓, Pinyin: Dahuting Han mu) of the late Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD), located in Zhengzhou, Henan province, China, was excavated in 1960-1961 and contains vault-arched burial chambers decorated with murals showing scenes of daily life.

Mural from the Dahuting Tomb (Chinese: 打虎亭汉墓, Pinyin: Dahuting Han mu) of the late Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220 AD), located in Zhengzhou, Henan province, China, was excavated in 1960-1961 and contains vault-arched burial chambers decorated with murals showing scenes of daily life. An Eastern Han lacquerware basket from the Lelang Commandery (modern North Korea) showing men wearing Hanfu robes, 108 BC - 133 AD, National Museum of Seoul

An Eastern Han lacquerware basket from the Lelang Commandery (modern North Korea) showing men wearing Hanfu robes, 108 BC - 133 AD, National Museum of Seoul- Painted lacquerware dish from the tomb of Zhu Ran (182-249 AD) in Anhui province, showing figures wearing Hanfu, Eastern Wu period

"Carpe diem": a mural painting showing the leisurely life scene, from a tomb in Chiu-ch'üan, Later Liang - Northern Liang

"Carpe diem": a mural painting showing the leisurely life scene, from a tomb in Chiu-ch'üan, Later Liang - Northern Liang A man wearing Hanfu robes and a woman dressing in Tsa-chü-ch'ui-shao-fu, from a lacquerware painting over wood, Northern Wei period, 5th century AD

A man wearing Hanfu robes and a woman dressing in Tsa-chü-ch'ui-shao-fu, from a lacquerware painting over wood, Northern Wei period, 5th century AD Male figure wearing Hanfu robes, from a lacquerware painting over wood, Northern Wei period, 5th century AD

Male figure wearing Hanfu robes, from a lacquerware painting over wood, Northern Wei period, 5th century AD_1.jpg) Admonitions of the Court Instructress (detail) by Ku K'ai-chih

Admonitions of the Court Instructress (detail) by Ku K'ai-chih_3.jpg) Admonitions of the Court Instructress (detail) by Ku K'ai-chih

Admonitions of the Court Instructress (detail) by Ku K'ai-chih_5.jpg) Admonitions of the Court Instructress (detail) by Ku K'ai-chih

Admonitions of the Court Instructress (detail) by Ku K'ai-chih_por_Ku_K'ai-chih_-_Duque_Yi_de_Wey.jpg) Duke Yi of Wey (衞懿公) from Wise and Benevolent Women by Ku K'ai-chih

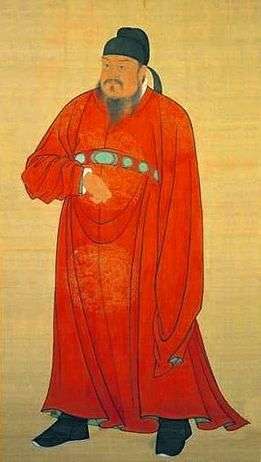

Duke Yi of Wey (衞懿公) from Wise and Benevolent Women by Ku K'ai-chih Yuanlingshan robes of a Tang emperor Li Yuan

Yuanlingshan robes of a Tang emperor Li Yuan Court ladies of the Tang from Li Xianhui's tomb, Qianling Mausoleum, dated 706.

Court ladies of the Tang from Li Xianhui's tomb, Qianling Mausoleum, dated 706. A painting of Tang Dynasty women playing with a dog, by artist Zhou Fang, 8th century.

A painting of Tang Dynasty women playing with a dog, by artist Zhou Fang, 8th century. Tang Dynasty Styled Hanfu

Tang Dynasty Styled Hanfu Buddhist donors of late T'ang dynasty.

Buddhist donors of late T'ang dynasty. A lady playing the pipa, T'ang dynasty.

A lady playing the pipa, T'ang dynasty. A noble lady from the painting Bodhisattva Who Leads the Way, Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms.

A noble lady from the painting Bodhisattva Who Leads the Way, Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms. Buddhist donatress Chang, Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms.

Buddhist donatress Chang, Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms..jpg) Pao-shan tomb wall-painting of Liao dynasty.

Pao-shan tomb wall-painting of Liao dynasty. A Buddhist donor from early Northern Sung dynasty.

A Buddhist donor from early Northern Sung dynasty. A male Buddhist donor from early Northern Sung dynasty.

A male Buddhist donor from early Northern Sung dynasty. A Sung dynasty mural reflecting a scene of the daily life of the occupant, found in a tomb unearthed in Tengfeng city.

A Sung dynasty mural reflecting a scene of the daily life of the occupant, found in a tomb unearthed in Tengfeng city. A Song Dynasty empress, wife of Emperor Zhenzong of Song

A Song Dynasty empress, wife of Emperor Zhenzong of Song- Imperial Portrait of the empress and wife to Emperor Qinzong of (1100–1161) of the Song Dynasty in China.

- A Ming Dynasty portrait of an Empress

Matteo Ricci and Xu Guangqi dressed in Ming Dynasty Hanfu.

Matteo Ricci and Xu Guangqi dressed in Ming Dynasty Hanfu. Taoist priest in red colored gown

Taoist priest in red colored gown A 1940s embroidered Han infant hat (繡帽; xiùmào) with double tigers, in the collection of The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis.

A 1940s embroidered Han infant hat (繡帽; xiùmào) with double tigers, in the collection of The Children’s Museum of Indianapolis.

Gallery of Modern Hanfu

Aoqun (襖裙)

Aoqun (襖裙) Banbi (半臂)

Banbi (半臂) Zhiju (直裾)

Zhiju (直裾) Bijia (比甲)

Bijia (比甲) Modern Hanfu

Modern Hanfu Jess Sum at 2005 Hong Kong Flower Show

Jess Sum at 2005 Hong Kong Flower Show Coming of age ritual for a Chinese girl (笄禮)

Coming of age ritual for a Chinese girl (笄禮) Daopao (道袍)

Daopao (道袍) Panling Lanshan (盤領襴衫)

Panling Lanshan (盤領襴衫) Shenyi (深衣)

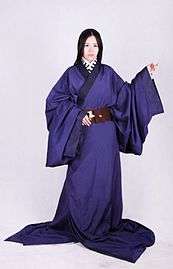

Shenyi (深衣) Zhiduo (直裰)

Zhiduo (直裰)

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hanfu. |

- Hanfu movement

- List of Han Chinese clothing

- Culture of China

- Chinese academic dress

- Guan Li

- Mandarin square

Notes and references

- ↑ 韩星 (2013-09-24). "当代汉服复兴运动的文化反思" (in Chinese). 中慧网. Retrieved 2014-01-18.

- ↑ 《漢書》云:『後數來朝賀,樂漢衣服制度。』

- 1 2 Michael R. Godley, "The End of the Queue:Hair as Symbol in Chinese History"

- ↑ Xu, Zhongguo Gudai Lisu Cidian, p. 7.

- ↑ Daoist Headdresses and Dress - Scarlet Robe

- ↑ High Priest of the Shaolin Monastery

- ↑ Stevens, Rebecca (1996). The kimono inspiration: art and art-to-wear in America. Pomegranate. pp. 131–142. ISBN 0-87654-598-3.

- ↑ Dalby, Liza (2001). Kimono: Fashioning Culture. Washington, USA: University of Washington Press. pp. 25–32. ISBN 0-295-98155-5.

- ↑ 《大南實錄・正編・第一紀・世祖實錄》,越南阮朝,國史館

- ↑ 《大南实录・正编・第一纪・卷五十四・嘉隆十五年七月条》,越南阮朝,國史館

- ↑ Finnane, Antonia (2008), Changing clothes in China: fashion, history, nation, Columbia University Press, pp. 44–46, ISBN 0-231-14350-8

- 1 2 http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06yglnh

- ↑ Costume in the Tang Dynasty chinaculture.org retrieved 2010-01-07

- ↑ Yoon, Ji-Won (2006). "Research of the Foreign Dancing Costumes: From Han to Sui-Tang Dynasty". 56. The Korean Society of Costume: 57–72.

- ↑ Costume in the Song Dynasty chinaculture.org retrieved 2010-01-07

- ↑ <The History of Chinese Ancient Clothing>Author:Chou XiBao 2011-01-01

- ↑ http://www.history.ubc.ca/sites/default/files/documents/readings/robinson_culture_courtiers_ch.8.pdf

- ↑ Costume in the Ming Dynasty chinaculture.org retrieved 2010-01-07

- ↑ Edward J. M. Rhoads (2000). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-0-295-98040-9.

- ↑ Twitchett, Denis; Fairbank, John K. (2008) Cambridge History of China Volume 9 Part 1 The Ch'ing Empire to 1800, p87-88

- ↑ 周锡保. 《中国古代服饰史》. 中国戏剧出版社. 2002-01-01: 449. ISBN 9787104003595.

- ↑ Edward J. M. Rhoads (2000). Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861–1928. University of Washington Press. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-0-295-98040-9.

- ↑ Gerolamo Emilio Gerini (1895). Chŭlăkantamangala: Or, The Tonsure Ceremony as Performed in Siam. Bangkok Times. pp. 11–.

- ↑ The Museum Journal. The Museum. 1921. pp. 102–.

- ↑ George Cockburn (1896). John Chinaman: His Ways and Notions. J. Gardner Hitt. pp. 86–.

- ↑ Robert van Gulik (15 November 2010). Poets and Murder: A Judge Dee Mystery. University of Chicago Press. pp. 174–. ISBN 978-0-226-84896-9.

- ↑ James William Buel (1883). Mysteries and Miseries of America's Great Cities: Embracing New York, Washington City, San Francisco, Salt Lake City, and New Orleans. A.L. Bancroft & Company. pp. 312–.

- ↑ Justus Doolittle (1876). Social Life of the Chinese: With Some Account of Their Religious, Governmental, Educational, and Business Customs and Opinions. With Special But Not Exclusive Reference to Fuhchau. Harpers. pp. 241–.

- ↑ http://www.forgottenbooks.com/readbook_text/Mysteries_and_Miseries_of_Americas_Great_Cities_1000494699/315

- ↑ Justus Doolittle, Social life of the Chinese : with some account of their religious, governmental, educational and business customs and opinions, with special but not exclusive reference to Fuhchau c

- ↑ https://archive.org/stream/sunlightshadowof00buelrich/sunlightshadowof00buelrich_djvu.txt

- ↑ East Asian History. Institute of Advanced Studies, Australian National University. 1994. p. 63.

- ↑ Michael R. Godley, The End of the Queue: Hair as Symbol in Chinese History

- ↑ Faure (2007), p. 164.

- ↑ Ebrey (1993)

- ↑ Ebrey, Patricia (1993). Chinese Civilization: A Sourcebook. Simon and Schuster. p. 271.

- ↑ Wakeman 1975b, p. 83.

- ↑ Justus Doolittle (1876). Social Life of the Chinese: With Some Account of Their Religious, Governmental, Educational, and Business Customs and Opinions. With Special But Not Exclusive Reference to Fuhchau. Harpers. pp. 242–.

Bibliography

- Zhou Xibao (1984), 【中國古代服飾史】 Zhongguo Gudai Fushi Shi (History of Ancient Chinese Costume), Beijing: Zhongguo Xiju.

- Zhou, Xun; Gao, Chunming; The Chinese Costumes Research Group (1984), 5000 Years of Chinese Costume, Hong Kong: The Commercial Press. ISBN 962-07-5021-7

- 許嘉璐 Xu Jialu (1991), 【中國古代禮俗辭典】 Zhongguo Gudai Lisu Cidian (Dictionary of Rituals and Customs of Ancient China).

- 沈從文 Shen Congwen (1999, 2006), 【中國古代服飾研究】 Zhongguo Gudai Fushi Yanjiu (Researches on Ancient Chinese Costumes), Shanghai: Shanghai Century Publishing Group. ISBN 7-80678-329-6

- 黃能馥, 陳娟娟 Huang Nengfu and Chen Juanjuan (1999), 【中華歷代服飾藝術】 Zhonghua Lidai Fushi Yishu (The Art of Chinese Clothing Through the Ages), Beijing.

- 華梅 Hua, Mei (2004), 【古代服飾】 Gudai Fushi (Ancient Costume), Beijing: Wenmu Chubanshe. ISBN 7-5010-1472-8

- Zhou, Xun; Gao, Chunming (1988). 5000 years of Chinese costumes. San Francisco: China Books & Periodicals. ISBN 9780835118224.