Silver Valley, Idaho

The Silver Valley is a region in the northwest United States, in the Coeur d'Alene Mountains in northern Idaho. It is noted for its mining heritage, dating back to the 1880s.[1]

Geography

Silver Valley is a narrow valley about 40 miles (64 km) in length, east of the city of Coeur d'Alene. The South Fork of the Coeur d'Alene River flows through the valley and Interstate 90 traverses the valley between Fourth of July Pass to the west and Lookout Pass on the Montana border.

Several towns are located in the valley, all in Shoshone County. These include (from west to east) Pinehurst, Smelterville, Kellogg, Wardner, Osburn, Silverton, Wallace, and Mullan. The Silver Valley has also been referred to as the Coeur d'Alene Valley and the Coeur d'Alene Mining District.

Mining

Although miners were originally lured to the general area by the promise of gold, the primary metals mined in the valley were silver, zinc, and lead. The total quantities produced are impressive: over a billion ounces of silver, 3 million tons of zinc, and 8 million tons of lead, totalling over $6 billion in value, ranking the valley among the top ten mining districts in world history.[2] During the 1970s, nearly half of the nation's silver production came from the Silver Valley.

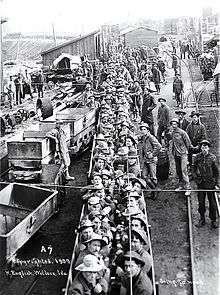

The area experienced a history of turbulent disputes between miners and mine owners more than a century ago. After nearly a century of vigorous mining and smelting activity, operations were severely curtailed in the early 1980s, resulting in massive unemployment and a significant loss of population. In addition to the economic difficulties, the valley has been saddled with significant environmental challenges.[1][3]

While some mining operations remain, the Silver Valley has focused its future upon recreational tourism and light manufacturing. The nearest major population center is the city of Spokane, Washington, which is 70 miles (110 km) west along I-90. The growing recreational city of Coeur d'Alene is halfway in between.

The extensive restoration efforts can be seen in the return of the tundra swans. Restoration means returning an area to its healthy natural habitat.[4]

Geology

The Coeur d'Alene (Silver Valley) Mining District is located in Proterozoic metasediments. The mined portion of the stratigraphic column in the Silver Valley, known as the Belt series, can be divided into six main formations, three of which have upper and lower parts. These are, from oldest to youngest: the Prichard Formation (lower and upper), Burke Formation, Revett Formation, St. Regis Formation (lower and upper), Wallace Formation (lower and upper), and Striped Peak Formation. Of these, all but the Striped Peak are ore-bearing.[5] All six of these formations are primarily composed of quartzite and argillite. Some limestone and dolomite also occur in the Wallace and Prichard, and a smaller amount of carbonate occurs in the St. Regis. Ripple marks and mud cracks occur throughout the series. Together, these imply a shallow marine depositional environment.[6]

The mining district occurs along the intersection of two major regional structural features. A large anticline extends through the district, running in a north-northwesterly direction.[6] The Lewis and Clark line – a series of strike-slip faults running across the Pacific Northwest – crosses this anticline, generally trending in an east-west direction. Within this mining district, the major structure of the lineament is the Osburn fault, which runs directly through the district’s most successful silver belts. Its 16-mile (27 km) displacement divides the district into two distinct parts, the southern Page Galena Belt, and the northern Golconda Lucky Friday Belt.[7]

Three main minerals make up most of the ore production in the Silver Valley. Galena (PbS or lead(II) sulfide) is the most important ore mineral found in the Coeur d’Alene District veins. Galena is present in veins throughout the district. Sphalerite ((Zn,Fe)S) is the second most important ore mineral, present in at least small amounts in most veins. The sphalerite is an important source of zinc throughout the ore belts. The third most abundant ore mineral is tetrahedrite (Cu,Fe)12Sb4S13. However, the tetrahedrite is responsible for the majority of the silver produced by the Silver Valley, as it’s the tetrahedrite interspersed in the galena of the district that makes it so argentiferous.[7]

Outdoor recreation

There are two alpine ski areas in the Silver Valley, both easily accessible from I-90. Lookout Pass is at the east end of the valley on the Montana border adjacent to the freeway. Silver Mountain is thirty miles west, accessed from the Kellogg city limits by the world's longest single-stage passenger gondola, a quarter mile (400 m) from the highway.

Bicycling is fast becoming a key recreational pursuit for both locals and tourists in the Silver Valley, with trails and paths ranging from easy to extreme. In addition to the challenging lift-served mountain-bike trails at Silver Mountain, there are two new major bike paths in the vicinity that use old railroad grades.

Lookout Pass ski area is also a primary staging area for the unique Route of The Hiawatha rail-trail, which begins in Montana and runs downhill through tunnels and over trestles to the North Fork of the St. Joe River, 15 miles (24 km) away. The trail is named for the Olympian Hiawatha passenger trains of the Milwaukee Road railroad, on whose abandoned tracks, trestles, and tunnels the gravel trail rests. One of the tunnels (Taft) is over 1.6 miles (2.6 km) in length. When completed, the Route of The Hiawatha will stretch from St. Regis, Montana to the very remote Pearson, Idaho, several miles north of Avery, (equidistantly south of Mullan).

The other trail is the Trail of the Coeur d'Alenes, completed in 2004. The paved bike path runs more than 72 miles (115 km), starting from Mullan in the east. It follows the South Fork of the Coeur d'Alene River down through the Silver Valley to the south end of Lake Coeur d'Alene, passing over a historic bridge, then up to Plummer in northwest Benewah County. The bike trail uses old right-of-way from the Union Pacific railroad.

See also

References

- 1 2 Steele, Karen Dorn (July 21, 2002). "Mining enriched region, left big mess". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. p. A9.

- ↑ Manning, Sue (January 31, 1980). "Glitter below surface in Idaho's Silver Valley". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Washington. Associated Press. p. 3.

- ↑ Steele, Karen Dorn (July 21, 2002). "EPA strikes vein of anger". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. p. A1.

- ↑ http://restorationpartnership.org

- ↑ Ridge, John Drew (1968). "Ore Deposits of the United States, 1933-1967". American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical, and Petroleum Engineers. 2: 1418–1428.

- 1 2 Hobbs, S. W.; Allen B. Griggs; Robert E. Wallace; Arthur B. Campbell (1965). "Geology of the Coeur D'Alene District Shoshone County, Idaho; Geological Survey Professional Paper 478": 1–139.

- 1 2 Park, Charles Frederick (1975). Ore Deposits. San Francisco, CA: W. H. Freeman.

- Conley, Cort (1982). Idaho for the Curious: A Guide. Cambridge, Idaho: Backeddy Books. pp. 457–497. ISBN 0-9603566-3-0. OCLC 8194915.

Further reading

- Historic Wallace Preservation Society (2010). The Silver Valley. Images of America. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0738581750. OCLC 711180847.

External links

- Silver Valley Rising - Documentary produced by Idaho Public Television

- Silver Valley Mining Association - based in Wallace

- Photo gallery of Walllace and the Silver Valley

- Route of The Hiawatha - U.S. Forest Service

- Trail of the Coeur d'Alenes - Idaho State Parks

- Kellogg Redefined - by Prof. Harley Johansen, University of Idaho - Spring 2006

- Bunker Hill Mining Company archives - University of Idaho Library: Special Collections

- Silver Valley cleanup - The Spokesman Review - Spokane - July 21–28, 2002

- An Idaho valley's perfect storm - Seattle Times - 01-July-2007 - reprint from The Idaho Statesman

Coordinates: 47°32′N 116°07′W / 47.54°N 116.12°W