Simon Metcalfe

| Simon Metcalfe | |

|---|---|

| Born |

1741 London, England |

| Died |

1794 Queen Charlotte Islands |

| Occupation | Maritime fur trader |

| Spouse(s) | Catherine Humphrey |

| Parent(s) | George and Anne Metcalfe |

| Signature | |

|

| |

Simon Metcalfe (also spelled Metcalf) (c. 1741–1794) was a British American surveyor and one of the first American maritime fur traders to visit the Pacific Northwest coast. As early visitors to the Hawaiian Islands, Metcalfe and his son Thomas unwittingly provided Western military weapons and advisors for Kamehameha I,[1] helping him win strategic battles and unify the Hawaiian Islands.

Life

Simon Metcalfe was born in London, England, April 23, 1741, the son of George and Anne Metcalfe, of Askrigg, Yorkshire but, due to a recent inheritance, living in Shadwell, London at the time of Simon's birth. Simon was baptized at 9 days old on May 1, 1741 at St.Pauls, Shadwell, County of Middlesex.< St. Paul's, Shadwell Parish Records> In his early life he trained for a career at sea with the East India Company.[2] He was married in Bolton on Swale, Yorkshire on May 12, 1763 to Catherine Humphrey, daughter of Thomas and Elizabeth Humphrey of that town. Simon stated at that time that his address was Dowgate Street, London and that he was a merchant. His brother Bernard Metcalfe was his witness. He and Catherine Humphrey had at least nine children. The family, Simon,Catherine and baby Elizabeth moved to the Province of New York about 1765, leaving son George in Yorkshire with Simon's brother Bernard to be educated. They settled first in New York City.[3] Metcalfe found employment as a surveyor and worked on the survey of the Fort Stanwix Treaty line in about 1769, and was promoted to Deputy Surveyor in the Province of New York by 1770.[3]

In 1771 Governor Dunmore of New York granted 30,000 acres (120 km2) of land to Simon Metcalfe and his wife. This land was called Prattsburgh and is now part of Swanton and Highgate, Vermont.[4] His family settled on this land and he established a fur trading post at the mouth of the Missisquoi River.[3]

During the American Revolutionary War Metcalfe supported the American cause. He was taken prisoner by the British and held in Montreal. Three of his children were born in Montreal around 1777, 1779 and 1781. In Early August 1781 their son George arrived with the fleet from England to join the family in Montreal, shortly before Simon and Thomas escaped. <Catherine Metcalfe Letter -British Library - Haldimand Papers> In 1783 Catherine Metcalfe and 8 children we released from Canada.<Return of American Prisoners 1783 - Haldimand Papers British Library>Property he owned on Lake Champlain was destroyed during the war.[5] After the war was over Metcalfe settled his family in Albany.[3]

Maritime fur trade

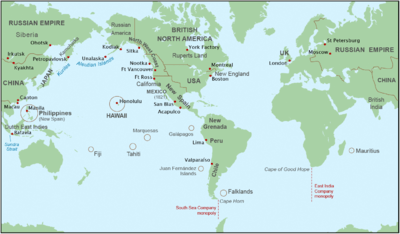

In the 1780s, Metcalfe took a consignment of seal furs from the Falkland Islands that were being stored in New York City. In 1787 he acquired the brig Eleanora (sometimes spelled Eleanor). In September 1787 he set sail on the Eleanora with a cargo of furs for China. He continued as a maritime fur trader for the next seven years. He probably did not return to New York after leaving in 1787.

Metcalfe might have been the first American to sail to the Pacific Northwest coast in search of furs.[6] In command of the Eleanora, he may have been on the Northwest Coast in 1787 or 1788, perhaps before the arrival of Robert Gray and John Kendrick in August and September 1788.[7]

In 1789 both Simon Metcalfe and his son Thomas Humphrey Metcalfe were caught up in the Nootka Crisis at Nootka Sound. Although the events at Nootka were mainly directed toward British merchant vessels, the Spanish naval officer Esteban José Martínez seized Thomas Metcalfe's small schooner, the Fair American. Simon Metcalfe approached Nootka Sound and the Eleanora was almost captured as well, but he managed to escape. The Fair American and its crew were taken to the Spanish naval base at San Blas. They were quickly released. The Metcalfes had planned to spend the winter in the Hawaiian Islands. After being released,Thomas Metcalfe sailed the Fair American to Hawaii, hoping to join his father.[8]

Olowalu massacre

The Eleanora under Simon Metcalfe arrived in the islands first. In Kohala on the island of Hawaiʻi, Metcalfe was greeted by local chief Kameʻeiamoku.[9] Metcalfe had the chief flogged for some infraction. Metcalfe believed in strong and immediate punishment when his rules were broken. By most accounts he was irascible and harsh. Metcalfe then sailed to the neighboring island of Maui to trade along the coast.[10] Kameʻeiamoku vowed revenge on whatever ship next came his way.[9]

Metcalfe ran into more trouble on the coast of Maui when a boat and sailor went missing. It was discovered that the boat had been stolen and the sailor killed. His punishment in this case became known as the Olowalu Massacre. He sailed to the village of the suspected thieves, Olowalu. Feigning peaceful intent, he invited the villagers to the Eleanora for trade. Many canoes gathered at the ship. Metcalfe directed them to come to one side, where he had loaded his cannon with ball and shot. He ordered a broadside fired at point-blank range, which blasted the vessels to pieces. About one hundred Native Hawaiians were killed and several hundred wounded.[11] Because Hawaiians considered Olowalu a pu'u honua, or place of refuge, this attack had profound and long-lasting consequences, ultimately undermining the site's cultural stability.[9][12] After the massacre, Metcalfe weighed anchor and sailed back to the island of Hawai'i. At Kealakekua Bay he began what seemed to be friendly trade for provisions.[9]

Capture of the Fair American

.jpg)

Meanwhile, Thomas Humphrey Metcalfe, arrived near Kawaihae Bay, in the Fair American. By coincidence the Fair American was the next ship to visit the territory of chief Kameʻeiamoku, who was eager for revenge. The schooner was manned by only four sailors plus its relatively inexperienced 19-year-old captain. It was easily captured by the Hawaiians. Thomas Metcalfe and his crew were killed. The only survivor was Isaac Davis, who was badly injured but for some reason spared. Kameʻeiamoku appropriated the ship, its guns, aummunition, and other valuable goods, as well as Isaac Davis himself. At the time no one was aware of the family relation between the captain of the Fair American and Simon Metcalfe, whose Eleanora was anchored at Kealakekua Bay, about 30 miles (48 km) away.[9][13] The Fair American and Davis were eventually given to King Kamehameha I.[11]

When Kamehameha learned about the capture of the Fair American he prohibited further contact between the natives and the Eleanora.[9] Metcalfe sent the boatswain John Young ashore to investigate. Young was captured, and Metcalfe was puzzled by the sudden silence.[9] He waited two days for Young to return, firing guns in hope that the sound would guide Young back. Finally, sensing danger or becoming frustrated, Metcalfe left and set sail for China, not knowing that his son had been killed not far away. He never learned about the attack on the Fair American or the fate of his son.[14]

These events mark a turning point in Hawaiian history. John Young and Isaac Davis were instrumental in Kamehameha's military ventures and his eventual conquest and unification of the Hawaiian Islands.[9] Young and Davis became respected translators and military advisors for Kamehameha. Their skill in gunnery, as well as the cannon from the Fair American, helped Kamehameha win many battles, including the Battle of Kepaniwai later in 1790 which defeated the forces of Maui. They married members of the royal family, raised families and received valuable lands.[10]

Death

Simon Metcalfe continued to trade around the Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean for another 4 years. He was in Macao in 1791. In 1792 he purchased a small French brig at Port Louis, Isle of France to serve as a tender to Elenora. He named this brig Ino and appointed his younger son Robert to command her. When the Elenora sank in the Indian Ocean in September 1792, Metcalfe took command of the Ino.[15][16]

In 1794 Metcalfe visited Houston Stewart Channel, at the southern end of the Haida Gwaii, and anchored in Coyah's Sound. Friendly trading with the local Haida natives of Chief Koyah began. Metcalfe let a great number come aboard the Ino. The Haida took advantage of their superiority in numbers and attacked.[17] Within a few minutes, and with no loss on the side of the natives, every man on board had been killed save one who fled into the rigging. The natives ordered the man to come down, which he did. He was kept as a slave for about a year. Eventually he was ransomed to a visiting ship and taken to Hawaii where he told his story to John Young, who passed it on to other captains who visited the islands.[18] The Ino was not the only ship captured by the Haida in 1794. The schooner Resolution, tender to the Boston ship Jefferson under captain Josiah Roberts, was seized by the Haida of Chief Cumshewa and, as with the Ino, all but one of the crew killed.[18]

References

- ↑ Settlement - 1800, Hawaiian Encyclopedia

- ↑ British Library - Haldimand Papers add. 21,841, f.11-12

- 1 2 3 4 Simon Metcalf, by Stefan Bielinski

- ↑ An Outline of Swanton's History, Swanton Historical Society

- ↑ Public Archives of Canada (1889). Canadian Archives. Public Archives of Canada. pp. 908–910. OCLC 8089253.

- ↑ Ruby, Robert H.; Brown, John A. (1976). The Chinook Indians: Traders of the Lower Columbia River. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8061-2107-9.

- ↑ Thrapp, Dan L. (1991). Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography: G-O. University of Nebraska Press. p. 583. ISBN 978-0-8032-9419-6.

- ↑ Blumenthal, Richard W. (2004). The Early Exploration of Inland Washington Waters: Journals and Logs from Six Expedition, 1786–1792. McFarland. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7864-1879-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hawaiian History, International Institute for Indigenous Resource Management

- 1 2 Coupler, A.D. (2009). Sailors and Traders: A Maritime History of the Pacific Peoples. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-0-8248-3239-1.

- 1 2 McDougall, Walter A. (2004). Let the Sea Make a Noise...: A History of the North Pacific from Magellan to MacArthur. HarperCollins. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-06-057820-6.

- ↑ http://www.mauimagazine.net/Maui-Magazine/May-June-2010/Olowalu-rsquos-Gift/ ["Olowalu's Gift"] Article about the restoration at Olowalu by Rita Goldman. Maui No Ka 'Oi Magazine Vol.14, No.3 (May 2010)

- ↑ Hill, Beth; Converse, Cathy (2009). The Remarkable World of Frances Barkley: 1769–1845. Heritage Group Distribution. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-894898-78-2.

- ↑ Kona Historical Society (1998). A Guide to Old Kona. University of Hawaii Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8248-2010-7.

- ↑ Narrative of John Bartlett

- ↑ Richards, Rhys (1991). Captain Simon Metcalfe: Pioneer Fur Trader in the Pacific Northwest, Hawaii and China 1787-1794. Kingston, Ontario: Limestone Press. ISBN 0-919642-37-3.

- ↑ Report for the Year 1957, Provincial Museum of Natural History and Anthropology, Province of British Columbia Department of Education

- 1 2 Pethick, Derek (1980). The Nootka Connection: Europe and the Northwest Coast 1790-1795. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. pp. 198–200. ISBN 0-88894-279-6.

External links

- Letter from Captain Metcalf, 1790, to King Kamehameha

- Surprise Visitor at Nootka Sound, Tacoma Public Library

- Cultural History of Three Traditional Hawaiian Sites (Chapter 3), Overview of Hawaiian History, National Park Service

- "Historic Kealakekua Bay". Papers of the Hawaiian Historical Society. Honolulu, Hawaii. 1928.

- Howay, Frederic William (1925). "Captain Simon Metcalfe and the Brig 'Eleanora'". Washington Historical Quarterly. 16 (2): 114–121. Retrieved 17 May 2010.