Slavery in Ethiopia

Slavery in Ethiopia has existed for centuries. The practice formed an integral part of the Afro-Asiatic-dominated Ethiopian society, from its earliest days through to the 20th century. Slaves were traditionally drawn from the negroid or some Nilotic groups that had mixed with bantu peoples like some Shanqella populations inhabiting Ethiopia's southern hinterland otherwise nilotic peoples were not victims. War captives were another source of slaves, though the perception, treatment and duties of these prisoners was markedly different.[1] Slaves were also sold abroad as part of the Arab slave trade, serving as concubines, bodyguards, servants and treasurers.[2] In response to pressure by Western Allies of World War II, Ethiopia officially abolished slavery and involuntary servitude after having regained its independence in 1942. On 26 August 1942, Haile Selassie issued a proclamation outlawing slavery.[3]

Overview

Slavery was fundamental to the social, political and economic order of medieval Ethiopia. Racism in the territory was traditionally mainly directed at the bantu/negroid ethnic minorities, as well as other individuals with similarly pronounced "Negroid" physical features. Collectively, these groups are locally known as barya, derogatory terms originally denoting slave descent, irrespective of the individual's family history.[4][5]

Historically, the negroid groups constituted most of the slave labour in the ruling local Afro-Asiatic societies.[6] The Abyssinians (Habesha highlanders) were also noted as having actively hunted the Shanqella during the 19th century.[7] Following the abolition of the slave trade in the 1940s, the freed Shanqella and barya were typically employed as unskilled labour.[6]

Traditionally, racism against perceived barya transcended class and remained in effect regardless of social position or parentage.[8] Although other populations in Ethiopia also faced varying degrees of discrimination, little of that adversity was by contrast on account of racial differences. It was instead more typically rooted in disparities in class and competition for economic status. The Oromo and Gurage were thus, for example, not considered by the highlander groups as being racially barya, owing to their similar physical features and common Afro-Asiatic ancestry.[6]

In terms of traditional perceptions, the negroids/bantu likewise racially contrast themselves from the Afro-Asiatic populations. The negroid Anywaa (Anuak) of southern Ethiopia consequently regard the Amhara, Oromo, Tigray and other Afro-Asiatic groups collectively as gaala ("red") in contradistinction to themselves.[9]

History

Conquest

In Ethiopia, slavery was legal and widespread; slave raiding was endemic in some areas, and slave trading was a fact of life.[10] The largest slavery-driven polity in the Horn of Africa before the nineteenth century was the Ethiopian Empire. Though its intercontinental slave trade was substantial, the Ethiopian Highlands were the largest consumer of slaves in the region.[11]

Before the imperial expansion to the south Asandabo, Saqa, Hermata and Bonga were the primary slave markets for the kingdom of Guduru, Limmu-Enaria, Jimma and Kaffa.[12] The merchant villages adjacent to these major markets of southwestern Ethiopia were invariably full of slaves, which the upper classes exchanged for the imported goods they coveted. The slaves were walked to the large distribution markets like Basso in Gojjam, Aliyu Amba and Abdul Resul in Shewa.[13] The primary source of slaves for the southern territories was the continuous wars & raids between various clans and tribes which has been going on for thousands of years, and it usually follows with large scale slavery that was very common during the battles of that era.[14][15][16][17][18] Slaves were often provided by Oromo and Sidamo rulers who raided their neighbors or who enslaved their own people for even minor crimes.[15] According to Donald Levine, it was common to see Boranas making slaves of Konso, Oromos being sold by other Oromo speaking clans and Afars making slaves of Amhara.[19][20] Famine is another source of slaves, and during times of recurrent drought and widespread cattle disease, slave markets throughout the country will be flooded with victims of famine. For instance, the Great famine of 1890-91 forced many people from the Christian north as well as southern Ethiopia to even sell their children and, at times, themselves to Muslim merchants.[21] Since religious law did not permit Christians to participate in the trade, Muslims dominated the slave trade, often going farther and farther afield to find supplies.[22]

In 1880, Menelik II, the Amhara ruler of the Ethiopian province of Shoa, began to overrun Oromia. This was largely in retaliation for the 16th century Oromo Expansion as well as the Zemene Mesafint ("Era of the Princes"), a period during which a succession of Oromo feudal rulers dominated the highlanders. Chief among these was the Yejju dynasty, which included Aligaz of Yejju and his brother Ali I of Yejju. Ali I founded the town of Debre Tabor, which became the dynasty's capital.[23] The Oromo expansion of 16th century absorbed many indigenous people of the kingdoms which were part of the Abyssinian empire. Some historically recorded peoples and kingdoms includes Kingdom of Damot, Kingdom of Ennarea, Sultanate of Showa, Sultanate of Bale, Gurage, Gafat, Ganz province, Maya, Hadiya Sultanate, Fatagar, Sultanate of Dawaro, Werjih, Gidim, Adal Sultanate, Sultanate of Ifat and other people of Abyssinian Empire were made Gabaros (serfs) while the native ancient names of the territories were replaced by the name of the Oromo clans who conquered it.[24][25][26] The Oromos adopted the Gabbaros in mass, adopting them to the qomo (clan) in a process known as Mogasa and Gudifacha. Through collective adoption, the affiliated groups were given new genealogies and started counting their putative ancestors in the same way as their adoptive kinsmen, and as a Gabarro they are required to pay their tributes and provide service for their conquerors.[26][27]

In southern Ethiopia the Gibe and Kaffa kings exercised their right to enslave and sell the children of parents too impoverished to pay their taxes.[28] Guma is one of the Gibe states that adjoins Enarea where Abba Bogibo rules and under his rule inhabitants of Guma were more than those of any other country doomed to slavery. Before Abba Rebu’s adoption of Islamism the custom of selling whole families for minor crimes done by a single individual was a custom.[29][30]

In the centralized Oromo states of Gibe valleys and Didesa, agriculture and Industry sector was done mainly by slave labour. The Gibe states includes Jemma, Gudru, Limmu-Enarya and Gera. Adjacent to western Oromo states exists the Omotic kingdom of Kaffa as well as other southern states in the Gojab and Omo river basins where slaves were the main agrarian producers.[31] In Gibe states one-third of the general population was composed of slaves while slaves were between half and two thirds of the general population in Kingdoms of Jimma, Kaffa, Walamo, Gera, Janjero and Kucha. Even Kaffa reduced the number of slaves by mid 19th century fearing it’s large bonded population.[32][33] Slave labour in the agriculture sector in southwest Ethiopia means that slaves constituted higher proportion of the general population when compared to the northern Ethiopia where agrarian producers are mainly free Gabbars.[33][34] Gabbars owns their own land as “rist” and their legal obligation is to pay one fifth of their produce as land tax and asrat, another one-tenth, with a total of one third of total production paid as tax to be shared between the gult holder and the state. In addition to these taxes, peasants of north Ethiopia have informal obligations where they will be forced “to undertake courvéé (forced labour)" such as farming, grinding corn, and building houses and fences that claimed up to one-third of their time.[35] This same Gabbar system was applied to South Ethiopia after the expansion of Shewan Kingdom while most of the southern rulling classes were made Balabates (gult holders) until emperor Haile Selassie abolished fiefdom (gultegna), the central institution of feudalism, in the south and north Ethiopia by 1966 after growing domestic pressure for land reform.[36][37][38]

In 1869, Menelik became king of Shewa. He thereafter set out to conquer Oromia, completely annexing the territory by 1900. The Oromo inhabitants were subsequently severely repressed by Menelik's troops, with the majority reduced to tenancy and paying heavy tributes for the use of land. Thousands were killed, and large numbers were also sold into slavery.[39] Menelik II and Queen Taitu personally owned 70,000 slaves.[40] Abba Jifar II also is said to have more than 10,000 slaves and allowed his armies to enslave the captives during a battle with all his neighboring clans.[41] This practice was common between various tribes and clans of Ethiopia for thousands of years.[15][16][17][18][19][20]

By the second half of the nineteenth century, Ethiopia provided an ever increasing number of slaves for the slave trade, as the geographical focus of the trade had shifted from the Atlantic basin to Ethiopia, the Nile basin and Southeast Africa down to Mozambique.[10] According to Donald, indeed a large part of the increased slave trade in the first half of the nineteenth century consisted of captives being sold by other neighbouring clans and tribes in the south & in Oromo areas.[42]

The nineteenth century witnessed an unprecedented growth in slavery in the country, especially in southern Oromo towns, which expanded as the influx of slaves grew. In the Christian highlands, especially in the province of Shoa, the number of slaves was quite large by the mid-century.[10] However, despite the war raids, the Oromo were not considered by the highlander groups as being racially barya, owing to their common Afro-Asiatic ancestry.[1]

Nature

Slavery as practiced within Ethiopia differed depending on the class of slaves in question. The "black" (Negroid) Shanqalla slaves in general sold for cheap. They were also mainly assigned hard work in the house and field.[1]

On the other hand, the "red" Oromo and Sidama slaves had a much higher value and were carefully sorted according to occupation and age: Very young children up to the age of ten were referred to as Mamul. Their price was slightly lower than that of ten to sixteen year old boys. Known as Gurbe, the latter young males were destined for training as personal servants. Men in their twenties were called Kadama. Since they were deemed beyond the age of training, they sold for a slightly lower price than the Gurbe. A male's value thus decreased with age. The most esteemed and desired females were girls in their teens, who were called Wosif. The most attractive among them were destined to become wives and concubines. Older women were appraised in accordance with their ability to perform household chores as well as their strength.[1]

Arab slave trade

The Indian Ocean slave trade was multi-directional and changed over time. To meet the demand for menial labor, slaves sold to Muslim slave traders by local slave raiders, Ethiopian chiefs and kings from the interior, were sold over the centuries to customers in Egypt, the Arabian peninsula, the Persian Gulf, India, the Far East, the Indian Ocean islands, Somalia and Ethiopia.[43]

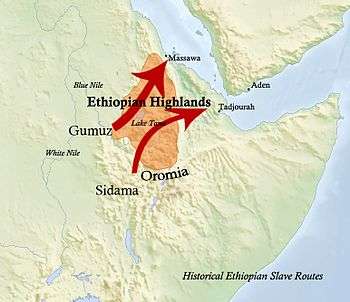

During the second half of the 19th century and early 20th century, slaves shipped from Ethiopia had a high demand in the markets of the Arabian peninsula and elsewhere in the Middle East. They were mostly domestic servants, though some served as agricultural labourers, or as water carriers, herdsmen, seamen, camel drivers, porters, washerwomen, masons, shop assistants and cooks. The most fortunate of the men worked as the officials or bodyguards of the ruler and emirs, or as business managers for rich merchants. They enjoyed significant personal freedom and occasionally held slaves of their own. Besides Javanese and Chinese girls brought in from the Far East, "red" (non-Negroid) Ethiopian young females were among the most valued concubines. The most beautiful ones often enjoyed a wealthy lifestyle, and became mistresses of the elite or even mothers to rulers.[44] The principal sources of these slaves, all of whom passed through Matamma, Massawa and Tadjoura on the Red Sea, were the southwestern parts of Ethiopia, in the Oromo and Sidama country.[2]

The most important outlet for Ethiopian slaves was undoubtedly Massawa. Trade routes from Gondar, located in the Ethiopian Highlands led to Massawa via Adwa. Slave drivers from Gondar took 100-200 slaves in a single trip to Massawa, the majority of whom were female.[2]

A small number of eunuchs were also acquired by the slave traders in the southern parts of Ethiopia.[45] Mainly consisting of young children, they led the most privileged lives and commanded the highest prices in the Islamic global markets because of their rarity. They served in the harems of the affluent or guarded holy sites.[44] Some of the young boys had become eunuchs due to the battle traditions that were at the time endemic to parts of southern Ethiopia. However, the majority came from the Badi Folia principality in the Jimma region, situated to the southeast of Enarea. The local Oromo rulers were so disturbed by the custom that they drove out of their kingdoms all who practiced it.[45]

Abolition

Initial efforts to abolish slavery in Ethiopia go as far back as the early 1850s, when Emperor Tewodros II outlawed the slave trade in his domain, albeit without much effect. Only the presence of the British in the Red Sea resulted in any real pressure on the trade.[10] By the mid-1890s, Menelik was actively suppressing the trade, destroying notorious slave market towns and punishing slavers with amputation.[46] Both Tewodros II and Yohannes IV also outlawed slavery but since all tribes were not against slavery and the fact that the country was surrounded on all sides by slave raiders and traders, it was not possible to entirely suppress this practice even by the 20th century.[47] According to Chris Prouty, Menelik prohibited Slavery while it was beyond his capacity to change the mind of his people regarding this age-old practice, that was widely prevalent throughout the country.[48]

To gain international recognition for his nation, Haile Selassie formally applied to join the League of Nations in 1919. Ethiopia's admission was initially rejected due to concerns about its slave-holding, slave trade and arms trade. Italy and Great Britain led the opposition, implying that independent Ethiopia was not yet civilised enough to join an international organization of free nations. It was eventually admitted in 1923, after signing the Convention of St. Germain to suppress slavery.[49][50] The League later appointed the Temporary Slavery Commission in 1924 to inquire into slavery worldwide. Despite the apparent measures to the contrary, slavery continued to be legal in Ethiopia even with its signing of the Slavery Convention of 1926.[3]

Italian Invasion

Using the intention to abolish slavery as one justification for that (the other was a border incident), in 1935 Italy invaded Ethiopia for the second time, this time managing to conquer the country. During Italian rule, the Italians definitely abolished slavery, issuing two laws in October 1935 and in April 1936 by which they allegedly freed 420 thousand people. After Italian defeat in second world war, Emperor Haile Selassie, who returned to power, abandoned his previous ideas about a slow and gradual abolition of slavery in favour of one that mirrored Italy’s total and drastic abrogation.[51]

Legacy

Although slavery was abolished in the 1940s, the effects of Ethiopia's longstanding peculiar institution lingered. As a result, former President of Ethiopia Mengistu Haile Mariam was virtually absent from the country's controlled press in the first few weeks of his seizure of power. He also consciously avoided making public appearances, here too on the belief that his "Negroid" appearance would not sit well with the country's deposed political elite, particularly the Amhara.[8] By contrast, Mengistu's rise to prominence was hailed by the southern Shanqella groups as a personal victory, with one of their own having made good.[5] Racial discrimination against the barya or Shanqella communities in Ethiopia still exists, affecting access to political and social opportunities and resources.[4]

Some slaves of Ethiopia or their descendants have also hold the highest positions. Abraha, the 6th century South Arabian ruler who led an army of 70,000, whom was appointed by the Axumites was a slave of a Byzantine Merchant in the Ethiopian port of Adulis.[52][53] Habte Giyorgis Dinagde and Balcha Abanefso were originally slaves taken as prisoners of war at Menelik’s court who ended up becoming so powerful, especially Habte Giorgis, became war minister and first prime minister of the empire who later became king-maker of Ethiopia after Menelik's death.[54][55] Ejegayehu Lema Adeyamo, mother of Emperor Menelik who actually founded modern Ethiopia, is said to be a slave.[56][57][58][59] Mengistu Haile Mariam, who declared a republic and ruled Ethiopia with socialism ideology, is also said to be the son of a former slave.[60]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Abir, Mordechai (1968). Ethiopia: the era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and re-unification of the Christian Empire, 1769-1855. Praeger. p. 57.

- 1 2 3 Clarence-Smith, edited by William Gervase (1989). The Economics of the Indian Ocean slave trade in the nineteenth century (1. publ. in Great Britain. ed.). London, England: Frank Cass. ISBN 0714633593.

- 1 2 Ethiopia : the land, its people, history and culture. [S.l.]: New Africa Press. ISBN 9987160247.

- 1 2 Uhlig, Siegbert (2003). Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A-C, Volume 1. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 489–490. ISBN 3447047461.

- 1 2 Thomson, Blair (1975). Ethiopia: The Country That Cut Off Its Head: A Diary of the Revolution. Robson Books. p. 117. ISBN 0903895501.

- 1 2 3 Congrès international des sciences anthropologiques et ethnologiques, Pierre Champion (1963). VIe [i.e. Sixième] Congrès international des sciences anthropologiques et ethnologiques, Paris, 30 juillet-6 août 1960: Ethnologie. 2 v. Musée de l'homme. p. 589.

- ↑ Fisher, Richard Swainson (1852). The Book of the World. p. 622.

- 1 2 Newsweek, Volume 85, Issues 1-8. Newsweek. 1975. p. 13.

- ↑ Katsuyoshi Fukui; Eisei Kurimoto; Masayoshi Shigeta (1997). Ethiopia in Broader Perspective: Papers of the XIIIth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, Kyoto, 12-17 December 1997, Volume 2. Shokado Book Sellers. p. 804. ISBN 487974977X.

- 1 2 3 4 Hinks, edited by Peter; editor, John McKivigan ; R. Owen Williams, assistant (2006). Encyclopedia of antislavery and abolition : Greenwood milestones in African American history. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 246. ISBN 0313331421. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - ↑ al.], edited by Keith Bradley ... [et. The Cambridge world history of slavery. (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 0521840686.

- ↑ W. G. Clarence-Smith The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Centuryy. Psychology Press (1989) pp. 108 Google Books

- ↑ Harold G. Marcus A History of Ethiopia. University of California Press (1994) pp. 55 Google Books

- ↑ W. G. Clarence-Smith The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Centuryy. Psychology Press (1989) pp. 107 Google Books

- 1 2 3 Harold G. Marcus A History of Ethiopia. University of California Press (1994) pp. 55 Google Books

- 1 2 Donald N. Levine Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press (2000) pp. 56 Google Books

- 1 2 Prof. Feqadu Lamessa History 101: Fiction and Facts on Oromos of Ethiopia. Salem-News.com (2013)

- 1 2 Donald N. Levine Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press (2000) pp. 136 Google Books

- 1 2 Donald N. Levine Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press (2000) pp. 136 Google Books

- 1 2 Donald N. Levine Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press (2000) pp. 156 Google Books

- ↑ Gwyn Campbell, Suzanne Miers, Joseph Calder Miller Women and Slavery: Africa, the Indian Ocean world, and the medieval north Atlantic, Volume 1. Ohio University Press (2007) pp. 225 Google Books

- ↑ Harold G. Marcus A History of Ethiopia. University of California Press (1994) pp. 55 Google Books

- ↑ Mordechai Abir, Ethiopia: The Era of the Princes; The Challenge of Islam and the Re-unification of the Christian Empire (1769-1855), (London: Longmans, 1968), p. 30

- ↑ Richard Pankhurst The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. The Red Sea Press (1997) pp. 35–300

- ↑ Shihāb al-Dīn Aḥmad ibn ʻAbd al-Qādir ʻArabfaqīh Futuh Al-Habasha: The conquest of Abyssinia: 16th century. (2003) pp. 1–417

- 1 2 Paul Trevor William Baxter, Jan Hultin, Alessandro Triulzi. Being and Becoming Oromo: Historical and Anthropological Enquiries. Nordic Africa Institute (1996) pp. 253–256

- ↑ Paul Trevor William Baxter, Jan Hultin, Alessandro Triulzi. Being and Becoming Oromo: Historical and Anthropological Enquiries. Nordic Africa Institute (1996) pp. 254

- ↑ Gwyn Campbell, Suzanne Miers, Joseph Calder Miller Women and Slavery: Africa, the Indian Ocean world, and the medieval north Atlantic, Volume 1. Ohio University Press (2007) pp. 225 Google Books

- ↑ Murray The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society: JRGS, Volume 13. (1843) pp. 225 Google Books

- ↑ International African Institute Ethnographic Survey of Africa, Volume 5, Issue 2. (1969) pp. 31 Google Books

- ↑ W. G. Clarence-Smith The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Centuryy. Psychology Press (1989) pp. 106 Google Books

- ↑ International African Institute Ethnographic Survey of Africa, Volume 5, Issue 2. (1969) pp. 31 Google Books

- 1 2 W. G. Clarence-Smith The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Centuryy. Psychology Press (1989) pp. 106 Google Books

- ↑ Daniel W. Ambaye Land Rights and Expropriation in Ethiopia. Springer (2015) pp. 41 Google Books

- ↑ Daniel W. Ambaye Land Rights and Expropriation in Ethiopia. Springer (2015) pp. 41 Google Books

- ↑ Lovise Aalen The Politics of Ethnicity in Ethiopia: Actors, Power and Mobilisation Under Ethnic Federalism. BRILL (2011) pp. 73 Google Books

- ↑ Thomas P. Ofcansky, LaVerle Bennette Berry Ethiopia, a Country Study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress (1993) pp. 110 Google Books

- ↑ Britannica encyclopaedia Fiefdom

- ↑ "Faqs - Oromo of Ethiopia". Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- ↑ Stokes, Jamie; Gorman, editor; Anthony; consultants, Andrew Newman, historical (2008). Encyclopedia of the peoples of Africa and the Middle East. New York: Facts On File. p. 516. ISBN 143812676X.

- ↑ Saïd Amir Arjomand Social Theory and Regional Studies in the Global Age (2014) pp. 242 Google Books

- ↑ Donald N. Levine Greater Ethiopia: The Evolution of a Multiethnic Society. University of Chicago Press (2000) pp. 156 Google Books

- ↑ Gwyn Campbell, The Structure of Slavery in Indian Ocean Africa and Asia, 1 edition, (Routledge: 2003), p.ix

- 1 2 Campbell, Gwyn (2004). Abolition and Its Aftermath in the Indian Ocean Africa and Asia. Psychology Press. p. 121. ISBN 0203493028.

- 1 2 Abir, Mordechai (1968). Ethiopia: the era of the princes: the challenge of Islam and re-unification of the Christian Empire, 1769-1855. Praeger. p. 56.

- ↑ Raymond Jonas The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire (2011) pp. 81 Google Books

- ↑ Jean Allain The Law and Slavery: Prohibiting Human Exploitation (2015) pp. 128 Google Books

- ↑ Chris Prouty Empress Taytu and Menilek II: Ethiopia, 1883-1910. Ravens Educational & Development Services (1986) pp. 16 Google Books

- ↑ Markakis, John. Ethiopia : the last two frontiers. Woodbridge, Suffolk: James Currey. p. 97. ISBN 1847010334.

- ↑ Vestal, Theodore M. The Lion of Judah in the New World Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia and the Shaping of Americans' Attitudes Toward Africa. Westport: ABC-CLIO. p. 21. ISBN 0313386218.

- ↑ Goitom, Hannibal. "Abolition of Slavery in Ethiopia". Retrieved 22 November 2015.

- ↑ J.A. Rogers World's Great Men of Color, Volume 1. (2011) Google Books

- ↑ J.Bernard Lewis "Abraha,+a+former+slave+of+a+Byzantine+merchant"&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj1gbnKldLMAhXoa5oKHVfgD0QQ6AEIGjAA#v=onepage&q=%22Abraha%2C%20a%20former%20slave%20of%20a%20Byzantine%20merchant%22&f=false Race and Slavery in the Middle East: An Historical Enquiry. Oxford University Press(1992) Google Books

- ↑ Messay Kebede Survival and modernization--Ethiopia's enigmatic present: a philosophical discourse. Red Sea Press (1999) pp. 162 Google Books

- ↑ Messay Kebede Survival and modernization--Ethiopia's enigmatic present: a philosophical discourse. Red Sea Press (1999) pp. 38 Google Books

- ↑ By Michael B. Lentakis Ethiopia: A View from Within. Janus Publishing Company Lim (2005) pp. 8 Google Books

- ↑ Marcus Garvey The Marcus Garvey and Universal Negro Improvement Association Papers, Vol. X: Africa for the Africans, 1923–1945. University of California Press (2006) pp. 630 Google Books

- ↑ Joel Augustus Rogers The Real Facts about Ethiopia. J.A. Rogers, Pubs (1936) pp. 11 Google Books

- ↑ Harold G. Marcus The life and times of Menelik II: Ethiopia, 1844-1913. Red Sea Press (1995) pp. 17 Google Books

- ↑ John Lamberton Harper The Cold War. OUP Oxford (2011) pp. 193 Google Books