Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiari

| Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiari | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Princess of Iran | |||||

| |||||

| Queen consort of Iran | |||||

| Tenure | 12 February 1951 – 6 April 1958 | ||||

| Born |

22 June 1932 Isfahan, Iran | ||||

| Died |

26 October 2001 (aged 69) Paris, France | ||||

| Burial | Westfriedhof, Munich | ||||

| Spouse |

Mohammed Reza Pahlavi (m. 1951; div. 1958) | ||||

| |||||

| House | Pahlavi (by marriage) | ||||

| Father | Khalil Esfandiary-Bakhtiari | ||||

| Mother | Eva Karl | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic, previously Shi'a Islam | ||||

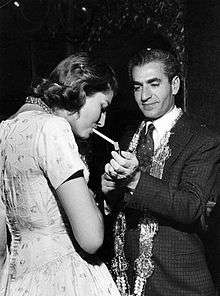

Princess Soraya of Iran (born Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiari, Lurish /Persian:ثریا اسفندیاری بختیاری, Sorayâ Esfandiyâri-Baxtiyâri; 22 June 1932 – 26 October 2001) was Queen of Iran, the second wife of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran, and a notable actress.

Early life and education

Soraya was the eldest child and only daughter of Khalil Esfandiary-Bakhtiary,[1] a Bakhtiary nobleman and Iranian ambassador to West Germany in the 1950s, and his German wife Eva Karl.[2] She was born in the English Missionary Hospital in Isfahan (Farsan) on 22 June 1932.[1][3] She had one sibling, a younger brother, Bijan.

Her family had long been involved in the Iranian government and diplomatic corps. An uncle, Sardar Assad, was a leader in the Iranian constitutional movement of the early 20th century.[4]

Soraya was raised in Berlin and Isfahan,[3] and educated in London and Switzerland.[3]

Marriage

In 1948, Soraya was introduced to the recently divorced Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, by Forough Zafar Bakhtiary, a close relative of Soraya's, via a photograph taken by Goodarz Bakhtiary, in London, per Forough Zafar's request. At the time Soraya had completed high school at a Swiss finishing school and was studying the English language in London.[4] They were soon engaged: the Shah gave her a 22.37 carat (4.474 g) diamond engagement ring.[5]

Soraya married the Shah at Marble Palace, Tehran, on 12 February 1951.[6] Originally the couple had planned to wed on 27 December 1950, but the ceremony was postponed due to the bride being ill.[7]

Though the Shah announced that guests should donate money to a special charity for the Iranian poor, among the wedding gifts were a mink coat and a desk set with black diamonds sent by Joseph Stalin; a Steuben glass Bowl of Legends designed by Sidney Waugh and sent by U.S. President and Mrs. Truman; and silver Georgian candlesticks from King George VI and Queen Elizabeth.[8] The 2,000 guests included Aga Khan III.

The ceremony was decorated with 1.5 tonnes of orchids, tulips and carnations, sent by plane from the Netherlands. Entertainment included an equestrian circus from Rome.[9] The bride wore a silver lamé gown studded with pearls and trimmed with marabou stork feathers,[10] designed for the occasion by Christian Dior.[11] She also wore a full-length female white-mink cape.

Following the marriage, Soraya headed the charity association in Iran.[12]

Infertility and divorce

Though the wedding took place during a heavy snow, deemed a good omen, the imperial couple's marriage had disintegrated by early 1958 owing to Soraya's apparent infertility. She had sought treatment in Switzerland and France, and in St. Louis with Dr. William Masters.[13] The Shah suggested that he take a second wife in order to produce an heir, but she rejected that option.[14] She left Iran in February and eventually went to her parents' home in Cologne, Germany, where the Shah sent his wife's uncle, Senator Sardar Assad in early March 1958, in a failed attempt to convince her to return to Iran.[15] On 10 March, a council of advisors met with the Shah to discuss the situation of the troubled marriage and the lack of an heir.[16] Four days later, it was announced that the imperial couple would divorce. It was, the 25-year-old queen said, "a sacrifice of my own happiness".[17] She later told reporters that her husband had no choice but to divorce her.[18]

On 21 March 1958, the Iranian New Year's Day, a weeping Shah announced his divorce to the Iranian people in a speech that was broadcast on radio and television; he said that he would not remarry in haste. The headline-making divorce inspired French writer Françoise Mallet-Joris to write a hit pop song, Je veux pleurer comme Soraya (I Want to Cry Like Soraya). The marriage was officially ended on 6 April 1958.

According to a report in The New York Times, extensive negotiations had preceded the divorce in order to convince Queen Soraya to allow her husband to take a second wife. The Queen, however, citing what she called the "sanctity of marriage", decided that "she could not accept the idea of sharing her husband's love with another woman."[14]

In a statement issued to the Iranian people from her parents' home in Germany, Soraya said, "Since His Imperial Majesty Mohammad Reza [sic] Shah Pahlavi has deemed it necessary that a successor to the throne must be of direct descent in the male line from generation to generation to generation, I will with my deepest regret in the interest of the future of the State and of the welfare of the people in accordance with the desire of His Majesty the Emperor sacrifice my own happiness, and I will declare my consent to a separation from His Imperial Majesty."[17]

After the divorce, the Shah, who had told a reporter who asked about his feelings for the former Queen that "nobody can carry a torch longer than me", indicated his interest in marrying Princess Maria Gabriella of Savoy, a daughter of the deposed Italian king Umberto II. In an editorial about the rumors surrounding the marriage of "a Muslim sovereign and a Catholic princess", the Vatican newspaper, L'Osservatore Romano, considered the match "a grave danger".[19]

Career as actress

Granted the royal title Princess of Iran after her divorce, she moved to France.

Princess Soraya launched a brief career as a film actress, for which she used only her first name. Initially, it was announced that she would portray Catherine the Great in a movie about the Russian empress by Dino De Laurentiis, but that project fell through.[20] Instead, she starred in the 1965 movie I tre volti (The Three Faces)[21] and became the companion of its Italian director, Franco Indovina (1932–72).[22] She also appeared as a character named Soraya in the 1965 movie She.[23]

After Indovina's death in a plane crash, she spent the remainder of her life in Europe, succumbing to depression, which she outlined in her 1991 memoir, Le Palais Des Solitudes (The Palace of Loneliness).

Later years in Paris

During her last years Princess Soraya lived in Paris on 46 avenue Montaigne. She occasionally attended social events like the parties given by the Duchess de La Rochefoucauld. Her friend and event organizer Massimo Gargia tried to cheer her up and make her meet young people.

Princess Soraya was a regular client of the hairdresser Alexandre Zouari. She also enjoyed going to the bar and the lobby of the Hotel Plaza Athénée located opposite her apartment.

She was often accompanied by her former lady-in-waiting and loyal friend Madame Chamrizad Firouzabadian. Another friend was the Parisian socialite, Lily Claire Sarran.

Princess Soraya did not communicate with the Shah's third wife Farah Diba, even when both of them lived in Paris.

Death

Princess Soraya died on 26 October 2001 of undisclosed causes in her apartment in Paris, France; she was 69.[24][25] Upon learning of her death, her younger brother, Bijan, sadly commented, "After her, I don't have anyone to talk to."[26][27] Bijan died one week later.

After a funeral at the American Cathedral in Paris on 6 November 2001 – which was attended by Princess Ashraf Pahlavi, Prince Gholam Reza Pahlavi, the Count and Countess of Paris, the young Duchess Rixa von Oldenburg, the Prince and Princess of Naples, Prince Michel of Orléans, and Princess Ira von Fürstenberg – she was buried in the Westfriedhof Quarter Nr. 143, in a cemetery in Munich, Germany, along with her parents and later brother.[28]

Since Soraya's death, several women have come forward claiming to be her illegitimate daughter, reportedly born in 1962, according to the Persian-language weekly Nimrooz; the claims have not been confirmed.[29] The newspaper also published an article in 2001 which suggested, without proof, that Princess Soraya and her brother had been murdered.[30]

The former queen's belongings were sold at auction in Paris in 2002, for more than $8.3 million.[31] Her Dior wedding dress brought $1.2 million.

Titles

| Styles of Princess Soraya of Iran | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | Her Imperial Highness |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial Highness |

| Alternative style | Ma'am |

Though her husband's title, shahanshah (King of Kings), is the equivalent of emperor, it was not until 1967 that a complementary feminine title, shahbanu or shahbanou (equivalent of empress), was created to designate the consort of a shah. Farah Pahlavi was the only woman to have this title. Until then, wives of shahs (including Soraya) bore the title Malake (which is comparable with that of queen), though in the popular press they frequently and incorrectly were called "empress".

Upon the divorce, Soraya ceased being a queen, but a day later she was granted the personal style and title Her Imperial Highness Princess Soraya of Iran.

- Miss Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiari (1932–1951)

- Her Majesty The Queen of Iran (1951–1958)

- Her Imperial Highness Princess Soraya of Iran (1958–2001)

Memoirs

Princess Soraya wrote two memoirs. The first, published in 1964 and published in the United States by Doubleday, was Princess Soraya: Autobiography of Her Imperial Highness. A decade before her death, she and a collaborator, Louis Valentin, wrote another memoir in French, Le Palais des Solitudes (Paris: France Loisirs/Michel Laffon, 1991), which was translated into English as Palace of Solitude (London: Quartet Books Ltd, 1992); ISBN 0-7043-7020-4.

Legacy

Soraya's divorce from the Shah inspired French songwriter Francoise Mallet-Jorris to write "Je veux pleurer comme Soraya" (I Want to Cry Like Soraya).[2][25] The French rose grower, François Meilland, bred a sunflower in the former queen's honor, which he called Empress Soraya.[32]

An Italian/German television movie about the princess's life, Soraya (a.k.a. Sad Princess) was broadcast in 2003, starring Anna Valle (Miss Italy 1995) as Soraya and Erol Sander as the Shah.[33] French actress Mathilda May appeared as the Shah's sister, Princess Shams Pahlavi.[34]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Zwischen Glück und Krone | Herself | Archive Footage |

| 1965 | I tre volti | Herself/Linda /Mrs. Melville | |

| 1965 | She | Soraya | |

| 1998 | Legenden | Herself | Episode: "Soraya" |

References

- 1 2 "Princess Soraya Esfandiari". Bakhtiari Family. Retrieved 10 October 2012.

- 1 2 Kadivar, Dairus (1 April 2007). "Stardust memories". The Middle East. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Earlier Marriages Ended In Divorce. Deposed Shah of Iran". The Leader Post. AP. 29 July 1980. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- 1 2 "Shah To Wed, Iran Hears". The New York Times. 10 October 1950. p. 12.

- ↑ "The Tribune, Chandigarh". The Tribune. India. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ↑ "Gifts for wedding". Daytona Beach Morning. Tehran. AP. 12 February 1951. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ "Wedding of Shah Postponed". The New York Times. 22 December 1950. p. 10.

- ↑ "Teheran Awaits Wedding". The New York Times. 11 February 1951. p. 35.

- ↑ "Iran's Shah To Wed In Splendor Today". The New York Times. 12 February 1951. p. 6.

- ↑ Shah of Iran Wed in Palatial Rites, The New York Times, 13 February 1951, p. 14

- ↑ "'Iconic royal wedding gowns". Harpers Bazaar.

- ↑ Hammed Shahidian (1 January 2002). Women in Iran: Gender politics in the Islamic republic. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-313-31476-6. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ↑ Maier, Thomas (2013). "6". Masters of Sex. Basic Books.

- 1 2 "Iran Shah Divorces His Childless Queen". The New York Times. 14 March 1958. p. 2.

- ↑ "Shah's Plea to Queen Held Vain". The New York Times. 6 March 1958. p. 3.

- ↑ "Iran Decision Pending". The New York Times. 11 March 1958. p. 2.

- 1 2 Queen of Iran Accepts Divorce As Sacrifice, The New York Times, 15 March 1958, p. 4.

- ↑ Soraya Arrives for U.S. Holiday, The New York Times, 23 April 1958, p. 35.

- ↑ Hofmann, Paul (24 February 1959). "Pope Bans Marriage of Princess to Shah". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ↑ Soraya Taking Screen Role, The New York Times, 8 October 1963, p. 48.

- ↑ I tre volti at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Princess Soraya, ex-wife of the Shah of Iran, dies in Paris". Hello! Magazine. 25 October 2001. Retrieved 27 June 2008.

- ↑ She at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ "Soraya, the second wife of Shah of Iran, dies". The Birmingham Post. 26 October 2001. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- 1 2 "Wife of Former Shah of Iran Dies". The Washington Post. Paris. AP. 25 October 2001. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ "Article Written By Dr Abbassi For Nimrooz Newspaper". Avairan. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ↑ "Soraya Esfandiari, Cyrus Kadivar". The Iranian. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ↑ "Royal News 2001". Angelfire. 14 December 2001. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ↑ "Tabarzadi". Avairan. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ↑ "Online.net Hébergement Mutualisé Professionnel". Avairan. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ↑ Zoeck, Irene (6 April 2003). "Fortune of Shah's former wife goes to German state". The Telegraph. Munich. Retrieved 16 July 2013.

- ↑ "François Meilland, 46". The New York Times. 17 June 1958. p. 29.

- ↑ "Making Sense of Iran". Khaleej Times. 3 October 2009. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- ↑ Soraya at the Internet Movie Database

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Soraya Esfandiary Bakhtiary. |

- Princess Soraya.com, souvenirs about Internet lessons

- Photo gallery

- Another gallery of her

- Bakhtiari World

- Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiari at the Internet Movie Database

| Iranian royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vacant Title last held by Fawzia of Egypt |

Queen consort of Iran 1951–1958 |

Vacant Title next held by Farah Diba |