Sprat

| This article is one of a series on |

| Commercial fish |

|---|

| |

| Large pelagic |

| billfish, bonito mackerel, salmon shark, tuna |

|

|

| Forage |

| anchovy, herring menhaden, sardine shad, sprat |

|

|

| Demersal |

| cod, eel, flatfish pollock, ray |

| Mixed |

| carp, tilapia |

A sprat is the common name applied to a group of forage fish belonging to the genus Sprattus in the family Clupeidae. The term is also applied to a number of other small sprat-like forage fish. Like most forage fishes, sprats are highly active small oily fish. They travel in large schools with other fish and swim continuously throughout the day.[1]

They are also recognized for their nutritional value as they contain high levels of polyunsaturated fats, considered beneficial to the human diet.They are eaten in many places around the world.[2] Sprats are sometimes passed for other fish; products sold as having been prepared from anchovies (since the 19th century) and sardines are sometimes prepared from sprats, as the authentic ones used to be less accessible. They are known for their smooth flavour and are easy to mistake for baby sardines.

Species

True sprats

True sprats belong to the genus Sprattus in the family Clupeidae. There are five species.

| Sprattus species | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length |

Common length |

Maximum weight |

Maximum age |

Trophic level |

Fish Base |

FAO | ITIS | IUCN status |

| New Zealand blueback sprat | Sprattus antipodum (Hector 1872) | 12.0 cm | 9.0 cm | kg | years | 3.0 | [3] | [4] | Not assessed | |

| Falkland sprat | Sprattus fuegensis (Blomefield, 1842) | 18.0 cm | 15.0 cm | kg | years | 3.4 | [5] | [6] | Not assessed | |

| New Zealand sprat | Sprattus muelleri (Klunzinger, 1879) | 13.0 cm | 10.0 cm | kg | years | 3.0 | [7] | [8] | Not assessed | |

| Australian sprat | Sprattus novaehollandiae (Valenciennes, 1847) | 14.0 cm | cm | kg | years | 3.0 | [9] | [10] | Not assessed | |

| European sprat* | Sprattus sprattus (Linnaeus, 1758) | 16.0 cm | 12.0 cm | kg | 6 years | 3.0 | [11] | [12] | [13] | Not assessed |

* Type species

Other sprats

The term is also commonly applied to a number of other small sprat-like forage fish which share characteristics of the true sprat. Apart from the true sprats, FishBase list another 48 species whose common names ends with "sprat". Some examples are:

| Sprat-like species | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common name | Scientific name | Maximum length |

Common length |

Maximum weight |

Maximum age |

Trophic level |

Fish Base |

FAO | ITIS | IUCN status |

| Black and Caspian Sea sprat | Clupeonella cultriventris (Nordmann, 1840) | 14.5 cm | 10 cm | kg | 5 years | 3.0 | [14] | [15] | [16] | Not assessed |

Characteristics

The average length of time from fertilization to hatching is approximately fifteen days, with environmental factors playing a major role in the size and overall success of the sprat.[17] The development of young larval sprat and reproductive success of the sprat have been largely influenced by environmental factors. Some of these factors that are affecting the sprat can be seen in the Baltic Sea, where specific gravity, water temperature, depth, and other such factors play a role in the success of the sprat. The amount of sprat over the last two decades has fluctuated due primarily to availability of zooplankton, a common food source, and also from overall changes in Clupeidae total abundance.[18] Although the overall survival rates of the sprat decreased in the late 1980s and early 1990s, there has been an increase in the last two decades.[18] Recent studies suggesting that there is a progression in the reproductive success of the sprat acknowledge that there has been a significant increase in spawning stock biomass.[19] One of the main concerns for reproductive success for the sprat include winters that are exceedingly cold, as cold temperatures, especially in the Baltic Sea, have been known to affect the development of sprat eggs and larvae.[17]

The metabolic rate of the sprat is highly influenced by environmental factors such as water temperature.[1] Several related fish such as the Atlantic Herring (C. harengus) have a much lower metabolic rate than that of the sprat. Some of the difference may be due to size differences among the related species[1] but the most important reason for high levels of metabolism for the sprat is their exceedingly high level of activity throughout the day.[1]

Distribution

Fish of the different species of sprat are found in various parts of the world including New Zealand, Australia, and parts of Europe. By far, the most highly studied location where the sprat, most commonly Sprattus sprattus, resides is the Baltic Sea, located in Northern Europe. The Baltic Sea provides the sprat with a highly diverse environment, with spatial and temporal potential allowing for successful reproduction.[19] One of the most well-known locations in the Baltic Sea where they forage for their food is the Bornholm Basin, located in the southern portion of the Baltic Sea.[18] Although the Baltic Sea has undergone several ecological changes during the last two decades, the sprat has dramatically increased in population.[20] One of the environmental changes that has occurred in the Baltic Sea since the 1980s includes a decrease in water salinity, due to a lack of inflow from the North Sea that contains high saline and oxygen content.[20]

Ecology

In the Baltic Sea, cod, herring, and sprat are considered the most important species.[19] Cod is the top predator while the herring and sprat are recognized primarily as prey.[21] This has been proven by many studies that analyze the stomach contents of such fish, often finding contents that immediately signify predation among the species.[19] Although cod primarily feed on adult sprat, sprat tend to feed on cod before they have been fully developed. The sprat tends to prey on the cod eggs and larvae.[17] Furthermore, sprat and herring are considered highly competitive for the same resources that are available to them. This is most present in the two species' vertical migration in the Baltic Sea, where they compete for the limited zooplankton that is available and necessary for their survival.[18]

Sprat are highly selective in their diet and are strict zooplanktivores that do not change their diet with fish size like some herring, but include only zooplankton in their diet.[18] They eat various species of zooplankton in accordance to changes in the environment, as temperature and other such factors affect the availability of their food. During autumn, sprat tend to have a diet high in Temora longicornis and Bosmina maritime. During the winter, their diet includes Pesudocalanus elongates.[18] Pseudocalanus is genus of the order calanoida and subclass copepoda that is important to the predation and diet of fish in the Baltic Sea.[22] In both autumn and winter, there has been a tendency for sprat to avoid eating Acartia spp. The main reason for sprat not including Acartia spp. in their diet is that they tend to be very small in size and have a high escape response to predators such as the herring and sprat. Although Acartia spp. may be present in large numbers, they also tend to dwell more towards the surface of the water, whereas the sprat, especially during the day, tend to dwell in deeper waters.[18]

Fisheries

-

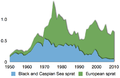

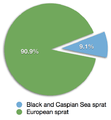

Global commercial capture of sprats in million tonnes 1950–2010[1]

-

The total capture of sprats in 2010 reported by the FAO was 667,000 tonnes.[1]

- ^ a b Based on data sourced from the relevant FAO Species Fact Sheets

As food

In Northern Europe, European sprats are commonly smoked and preserved in oil, which retains a strong smoky flavor.

Sprat, if smoked, is considered to be one of the foods highest in purine content.[23] People who suffer from gout or high uric acid in the blood should avoid eating such foods. Sprat, most importantly contains long-chained polyunsaturated fatty acids, including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).[24] Present in amounts that are comparable to Atlantic Salmon, and up to seven times higher in EPA and DHA than common fresh fillets of gilthead, the sprat contains approximately 1.43g/100g of these polyunsaturated fatty acids that have been found to help prevent mental, neural, and cardiovascular diseases.[24] Further comparison of the canned fish that contain high amounts of polyunsaturated fatty acids show that although this is a canned species, the content of polyunsaturated fatty acids exceeds that of some terrestrial animal products such as Thai fermented pork sausage that contains only 0.01g/100g DHA, with no EPA being detected at all.[24]

-

Sprattus sprattus, the European sprat

-

Creel with sprat, National Fishery Museum, Belgium

-

Oven to smoke sprat, National Fishery Museum, Belgium

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Meskendahl, L., J.-P. Herrmann, and A. Temming. "Effects of Temperature and Body Mass on Metabolic Rates of Sprat, Sprattus Sprattus L." Marine Biology 157.9 (2010): 1917–1927. Academic Search Premier. Web. 26 Nov. 2011. p. 1925

- ↑ Sprats Fried in Batter

- ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Sprattus antipodum" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- ↑ "Sprattus antipodum". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Sprattus fuegensis" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- ↑ "Sprattus fuegensis". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Sprattus muelleri" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- ↑ "Sprattus muelleri". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Sprattus novaehollandiae" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- ↑ "Sprattus novaehollandiae". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Sprattus sprattus" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- ↑ Sprattus sprattus (Linnaeus, 1758) FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 2012.

- ↑ "Sprattus sprattus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2012). "Clupeonella cultriventris" in FishBase. April 2012 version.

- ↑ Clupeonella cultriventris (Nordmann, 1840) FAO, Species Fact Sheet. Retrieved April 2012.

- ↑ "Clupeonella cultriventris". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved April 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 3 Nissling, Anders. "Effects Of Temperature On Egg And Larval Survival Of Cod (Gadus Morhua) And Sprat (Sprattus Sprattus) In The Baltic Sea – Implications For Stock Development." Hydrobiologia 514.1-3 (2004): 115-123. Academic Search Premier. Web. 24 Nov. 2011. p. 121

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Casini, Michele, Cardinale, Massimiliano, and Arrheni, Fredrik. “Feeding preferences of herring (Clupea harengus) and sprat (Sprattus sprattus) in the southern Baltic Sea.” ICES Journal of Marine Science, 61 (2004): 1267-1277. Science Direct. Web. 22 November 2011. p. 1268.

- 1 2 3 4 Friedrich W. Köster, et al. "Developing Baltic Cod Recruitment Models. I. Resolving Spatial And Temporal Dynamics Of Spawning Stock And Recruitment For Cod, Herring, And Sprat." Canadian Journal Of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences 58.8 (2001): 1516. Academic Search Premier. Web. 21 Nov. 2011. p. 1516.

- 1 2 Casini, Michele, Massimiliano Cardinale, and Joakim Hjelm. "Inter-Annual Variation In Herring, Clupea Harengus, And Sprat, Sprattus Sprattus, Condition In The Central Baltic Sea: What Gives The Tune?." Oikos 112.3 (2006): 638-650. Academic Search Premier. Web. 22 Nov. 2011. p. 638.

- ↑ Maris Plikshs, et al. "Developing Baltic Cod Recruitment Models. I. Resolving Spatial And Temporal Dynamics Of Spawning Stock And Recruitment For Cod, Herring, And Sprat." Canadian Journal Of Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences 58.8 (2001): 1516. Academic Search Premier. Web. 23 Nov. 2011, p.1517

- ↑ Renz, Jasmin, Peters, Janna, Hirch, Hans-Jürgen. "Life cycle of Pseudocalanus acuspes Giesbrecht (Copepoda,Calanoida) in the Central Baltic Sea: II. Reproduction, growth and secondary production." Marine Biology, 151 (2007):515-527. Springer Link. Web. 4 December 2011. p. 515

- ↑ Various food types and their purine content http://www.acumedico.com/purine.htm

- 1 2 3 Galina S. Kalachova, et al. "Content of essential polyunsaturated fatty acids in three canned fish species." International Journal of Food Sciences & Nutrition 60.3 (2009): 224-230. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Web. 26 Oct. 2011. p.224.

References

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2006). Species of Sprattus in FishBase. March 2006 version.

- Tony Ayling & Geoffrey Cox, Collins Guide to the Sea Fishes of New Zealand, (William Collins Publishers Ltd, Auckland, New Zealand 1982) ISBN 0-00-216987-8

.png)