Stalag Luft III

| Stalag Luft III | |

|---|---|

| Sagan, Lower Silesia | |

|

Model of the set used to film the movie The Great Escape. It depicts a smaller version of a single compound in Stalag Luft III. The model is now at the museum near where the prison camp was located. | |

Stalag Luft III Sagan, Germany (pre-war borders, 1937) | |

| Coordinates | 51°35′55″N 15°18′27″E / 51.5986°N 15.3075°E |

| Type | Prisoner-of-war camp |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by |

|

| Site history | |

| In use | March 1942 – January 1945 |

| Events | The "Great Escape" |

| Garrison information | |

| Past commanders | Oberst Friedrich Wilhelm von Lindeiner-Wildau |

| Occupants | Allied air crews |

Stalag Luft III (German: Stammlager Luft, or main camp for aircrew) was a Luftwaffe-run prisoner-of-war camp during World War II that housed captured air force servicemen. It was in the German province of Lower Silesia near the town of Sagan (now Żagań in Poland), 160 kilometres (100 miles) southeast of Berlin. The site was selected because it would be difficult to escape by tunnelling through sandy soil.

The camp is best known for two famous prisoner escapes that took place there by tunnelling, which were depicted in the films The Great Escape (1963) and The Wooden Horse (1950), and the books by former prisoners Paul Brickhill and Eric Williams from which these films were adapted.

The camp was very secure. Despite being an officers-only camp, it was referred to as a Stalag camp rather than Oflag (Offizier Lager) as the Luftwaffe had their own nomenclature. Later camp expansions added compounds for non-commissioned officers. Captured Fleet Air Arm (Royal Navy) aircrew were considered to be Air Force by the Luftwaffe and no differentiation was made. At times non-airmen were interned.

The first compound (East Compound) of the camp was completed and opened on 21 March 1942. The first prisoners, or kriegies, as they called themselves (from Kriegsgefangene), to be housed at Stalag Luft III were British and Commonwealth airmen as well as Fleet Air Arm officers, arriving in April 1942. The Centre compound was opened on 11 April 1942, originally for British sergeants but by the end of 1942 replaced by Americans. The North Compound for British airmen, where the Great Escape occurred, opened on 29 March 1943. A South Compound for Americans was opened in September 1943 and USAAF prisoners began arriving at the camp in significant numbers the following month and the West Compound was opened in July 1944 for U.S. officers. Each compound consisted of fifteen single story huts. Each 3.0-by-3.7-metre (10-by-12-foot) bunkroom slept fifteen men in five triple deck bunks. Eventually the camp grew to approximately 24 hectares (60 acres) in size and housed about 2,500 Royal Air Force officers, about 7,500 U.S. Army Air Forces, and about 900 officers from other Allied air forces, for a total of 10,949 inmates, including some support officers.[1][2]

The prison camp had a number of design features that made escape extremely difficult. The digging of escape tunnels, in particular, was discouraged by several factors: the barracks housing the prisoners were raised approximately 60 centimetres (24 in) off the ground to make it easier for guards to detect tunnelling; the camp had been constructed on land that had a very sandy subsoil; the surface sand was bright yellow, so it could easily be detected if anyone dumped the darker, grey dirt found beneath it above ground, or even just had some of it on their clothing. The loose, collapsible sand meant the structural integrity of any tunnel would be very poor. A third defence against tunnelling was the placement of seismograph microphones around the perimeter of the camp, which were expected to detect any sounds of digging.

The first escape occurred in October 1943 in the East Compound. Conjuring up a modern Trojan Horse the kriegies (prisoners) constructed a gymnastic vaulting horse largely from plywood from Red Cross parcels. The horse was designed to conceal men, tools and containers of soil. Each day the horse was carried out to the same spot near the perimeter fence and while prisoners conducted gymnastic exercises above, a tunnel was dug. At the end of each working day, a wooden board was placed over the tunnel entrance and covered with surface soil. The gymnastics disguised the real purpose of the vaulting horse and kept the sound of the digging from being detected by the microphones. For three months three prisoners, Lieutenant Michael Codner, Flight Lieutenant Eric Williams and Flight Lieutenant Oliver Philpot, in shifts of one or two diggers at a time, dug over 30 m (100 ft) of tunnel, using bowls as shovels and metal rods to poke through the surface of the ground to create air holes. No shoring was used except near the entrance. On the evening of 19 October 1943, Codner, Williams and Philpot made their escape.[3] Williams and Codner were able to reach the port of Stettin where they stowed away on a Danish ship and eventually returned to Britain. Philpot, posing as a Norwegian margarine manufacturer, was able to board a train to Danzig (now Gdańsk) and from there stowed away on a Swedish ship headed for Stockholm, from where he was repatriated to Britain. Accounts of this escape were recorded in the book Goon in the Block (later retitled The Wooden Horse) by Williams, the book Stolen Journey by Philpot and the 1950 film The Wooden Horse.[4]

Compared with "The Great Escape" the result was the same – three men got home. The earlier escape involved a small investment in effort and resources, and no loss of life. The later one involved significantly greater quantities of labour and contraband, and resulted in 50 deaths. Fifty years later a handful of survivors of the Great Escape who were interviewed for a television programme agreed that their escape had not been worth it.[5] Other internees, however, believe that the escapes were justified by the morale boost they provided.[6][7]

Camp life

The recommended dietary intake for a normal healthy inactive man is 2,150 kilocalories (9,000 kilojoules).[8] Luft III issued "Non-working" German civilian rations which allowed 1,928 kcal (8,070 kJ) per day, with the balance made up from American, Canadian, and British Red Cross parcels and items sent to the POWs by their families.[9][10] As was customary at most camps, Red Cross and individual parcels were pooled and distributed to the men equally. The camp also had an official internal bartering system called a Foodacco – POWs marketed surplus goods for "points" that could be "spent" on other items.[11] The Germans paid captured officers the equivalent of their pay in internal camp currency (lagergeld), which was used to buy what goods were made available by the German administration. Every three months, a weak beer was made available in the canteen for sale. As NCOs did not receive any "pay" it was the usual practice in camps for the officers to provide one-third for their use but at Luft III all lagergeld was pooled for communal purchases. As British government policy was to deduct camp pay from the prisoners' military pay, the communal pool avoided the practice in other camps whereby American officers contributed to British canteen purchases.[9]

Stalag Luft III had the best-organised recreational program of any POW camp in Germany. Each compound had athletic fields and volleyball courts. The prisoners participated in basketball, softball, boxing, touch football, volleyball, table tennis and fencing, with leagues organised for most. A 6.1 m × 6.7 m × 1.5 m (20 ft × 22 ft × 5 ft) pool used to store water for firefighting, was occasionally available for swimming.[9]

A substantial library with schooling facilities was available, where many POWs earned degrees such as languages, engineering or law. The exams were supplied by the Red Cross and supervised by academics such as a Master of King's College who was a POW in Luft III. The prisoners also built a theatre and put on high-quality bi-weekly performances featuring all the current West End shows.[12] The prisoners used the camp amplifier to broadcast a news and music radio station they named Station KRGY, short for Kriegsgefangener (POWs) and also published two newspapers, the Circuit and the Kriegie Times, which were issued four times a week.[9]

To prevent Germans from infiltrating the prisoner population, newcomers to the camp had to be vouched for by two POWs who knew the prisoner by sight. Anyone who failed this requirement was severely interrogated and assigned a rota of POWs who had to escort him at all times until he was deemed to be genuine. Several infiltrators were discovered by this method and none is known to have escaped detection in Luft III.

The German guards were referred to as "Goons" and, unaware of the Allied connotation, willingly accepted the nickname after being told it stood for "German Officer Or Non-Com".[13] German guards were followed everywhere they went by prisoners, who used an elaborate system of signals to warn others of their location. The guards' movements were then carefully recorded in a logbook kept by a rota of officers. Unable to stop what the prisoners called the "Duty Pilot" system, the Germans allowed it to continue and on one occasion the book was used by Kommandant von Lindeiner to bring charges against two guards who had slunk away from duty several hours early.[14]

The camp's 800 Luftwaffe guards were either too old for combat duty or young men convalescing after long tours of duty or from wounds. Because the guards were Luftwaffe personnel, the prisoners were accorded far better treatment than that granted to other POWs in Germany.[9] Deputy Commandant Major Gustav Simoleit, a professor of history, geography and ethnology before the war, spoke several languages, including English, Russian, Polish and Czech. Transferred to Sagan in early 1943, he proved sympathetic to allied airmen. Ignoring the ban against extending military courtesies to POWs, he provided full military honours for Luft III POW funerals, including one for a Jewish airman.[15]

The camp had many amenities brought by Swedish attorney Henry Söderberg,[16] who was the YMCA representative to the area, and frequently brought to its camps not only sports equipment, and religious items supporting the work of chaplains, but also the wherewithal for each camp's band and orchestra, and well-equipped library.[17]

Liberation

Just before midnight on 27 January 1945, with Soviet troops only 26 km (16 mi) away, the remaining 11,000 POWs were marched out of camp with the eventual destination of Spremberg. In below-freezing temperatures and 15 cm (6 in) of snow, 2,000 prisoners were assigned to clear the road ahead of the main group. After a 55 km (34 mi) march, the POWs arrived in Bad Muskau where they rested for thirty hours, before marching the remaining 26 km (16 mi) to Spremberg. On 31 January, the South Compound prisoners plus 200 men from the West Compound were sent by train to Stalag VII-A at Moosburg followed by the Centre compound prisoners on 7 February. Some 32 prisoners escaped during the march to Moosburg but all were recaptured.[18] The North, East and remaining West compound prisoners at Spremberg were sent to Stalag XIII-D at Nürnberg on 2 February. With the approach of U.S. forces on 13 April, the American prisoners at XIII-D were marched to Stalag VII-A. While the majority reached VII-A on 20 April, many had dropped out on the way with the German guards making no attempt to stop them. Built to hold 14,000 POWs, Stalag VII-A now held 130,000 from evacuated stalags with 500 living in barracks built for 200. Some chose to live in tents while others slept in air raid slit trenches.[19] The U.S. 14th Armored Division liberated the prisoners of VII-A on 29 April.[9]

Kenneth W. Simmons' book Kriegie (1960) vividly describes the life of POWs in the American section of Stalag Luft III, during the final months of the war, ending with the winter forced-march away from the camp, escaping the advancing Soviet troops and eventually being liberated.

Notable prisoners

Notable military personnel held at Stalag Luft III included:

- Squadron Leader Phil Lamason RNZAF, who was also the senior officer in charge of 168 Allied airmen initially held at Buchenwald concentration camp.

- Charles W. Sandman, Jr. spent over seven months in Stalag Luft III. Sandman entered the camp weighing approximately 86 kg (190 lb) and left weighing 57 kg (125 lb). In his diary, Sandman describes the harsh winters and struggles to secure rations sent by the American Red Cross.

- David M. Jones, Commander of the 319th Bombardment Group in North Africa, was an inmate at Stalag Luft III for two and a half years. According to his biography he led the digging team on Harry. In early 1942 Jones took part in the Doolittle Raid undertaken in retaliation for the December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.

- Robert M. Polich, Sr., also of the United States Army Air Forces, who received the Distinguished Flying Cross, later featured in the short film Red Leader on Fire which was submitted for the Minnesota's Greatest Generation short film festival in 2008.[20]

- The highest-ranking USAAF officer shot down and captured in the European Theatre of Operations, Col. Delmar T. Spivey, on 12 August 1943, serving as an observer on a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress of the 407th Bomb Squadron, 92d Bomb Group.[21][22][23] As the USAAF expert on aerial gunnery, he was on the mission to evaluate how to improve gun turrets.[24][25] (MACR 655)[26] Spivey assumed command as Senior American Officer (SAO) of Centre Compound in August 1943. Amazed by the prisoners' ingenuity, he had a carefully coded history of the camp created, so that future POWs would not have to "re-invent the wheel." This carefully hidden record was retrieved and carried at no little risk when the camp was hastily evacuated in late January 1945, as the Germans marched the prisoners away from the rapidly advancing Russian armies. The documents served as the basis and initial impetus for "Stalag Luft III – The Secret Story", a definitive history of the camp, by Col. Arthur A. Durand, USAF (Ret.).[27]

- Canadian Flight Lieutenant Gordon Miller tagged "Moose Miller", helped carry the Wooden Horse in and out each day under the German guns without faltering with the weight of two concealed diggers and a day's worth of earth. He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for repairing a damaged Wellington in flight and allowing the crew to parachute to safety.[28]

- Canadian William (Bill) James Cameron (born 3 August 1920, Stony Plain, Alberta) was fascinated with aircraft from an early age. When given the opportunity to live and work in Chicago with his Uncle WJ Cameron, Bill also enrolled in flying lessons, later joining the RCAF. Flight Lieutenant Cameron flew Spitfires; he was shot down initially over the English Channel, parachuting to safety, then again when stationed in Tunisia, he was shot down over the Straits of Messina, Sicily on 26 July 1943. Cameron was captured by the Italians but was turned over to the Germans, spending the remainder of the war in Stalag Luft III. He assisted with digging the tunnel Harry and was one of the 73 escapees able to taste freedom briefly. After spending two or three days on the run, Cameron was found by military dogs sleeping in a farmer's barn and was sent back to solitary confinement at Stalag Luft III. After the evacuation of the camp and walking for several months, Cameron was taken to England where he spent one month in hospital regaining his strength as he was severely malnourished. When he returned to Canada, the Canadian Air Force provided Cameron with a university education at UBC. He attempted to forget as much of his experience in the camp as possible but had nightmares for decades.

- Flight Lieutenant George Harsh RCAF was a member of the Great Escape's executive committee and the camp "security officer". He was one of the 19 "suspects" transferred to Belaria compound shortly before the escape. Born in 1910 to a wealthy and prominent Georgia family, Harsh, a medical student, was sentenced to life imprisonment in 1929 for the self-confessed thrill killing of a grocer. He saved the life of a fellow prisoner by performing an emergency appendectomy, for which Georgia governor Eugene Talmadge released him on parole in November 1940 and finally granted him a full pardon. He then joined the RCAF as a tail gunner and after being shot down in 1942 was sent to Stalag Luft III. In 1971 he published his autobiography which has since been translated into German and Russian.[29]

- Another notable prisoner was P. P. Kumaramangalam DSO, MBE of the then British Indian Army and the future Chief of the Indian Army.

Some held at Stalag Luft III went on to notable careers in the entertainment industry:

- British actor Rupert Davies had many roles in productions at the theatre in the camp; his most famous roles on film and TV may have been Inspector Maigret in the BBC series Maigret that aired over 52 episodes from 1960 to 1963 and George Smiley in the movie The Spy Who Came in from the Cold.

- Singer Cy Grant, born in British Guiana, served as a Flight Lieutenant in the RAF and spent two years as a prisoner of war, including time at Stalag Luft III. After the war he qualified as a barrister but went on to be a singer, actor and author. His was the first black face to be regularly seen on British television, singing the news as "topical calypsos" (punning on "tropical") on the BBC Tonight programme.[30][31]

- Wally Kinnan, one of the first well known U.S. television broadcast meteorologists, was also in the camp.

- The actor Peter Butterworth and the writer Talbot Rothwell were both inmates of Stalag Luft III; they became friends and later worked together on the Carry On films. Butterworth was one of the vaulters covering for the escapees during the escape portrayed by the book and film The Wooden Horse.[32] After the war and as an established actor, Butterworth auditioned for the film but "didn't look convincingly heroic or athletic enough" according to the makers of the film.[33]

- American novelist and screenwriter Len Giovannitti was held in Stalag Luft III's Center Compound. A navigator with the 742nd Bomb Squadron, 455th Bomb Group of the Fifteenth Air Force, he was on his 50th mission when his B-24 Liberator was shot down over Austria on 26 June 1944. A POW for nearly a year, he incorporated his experiences, including the winter march to Germany and liberation in Bavaria, in a novel he wrote between April 1953 and May 1957, The Prisoners of Combine D, published by Henry Holt and Company (ASIN: B0007E6KMG).

- Writer and broadcaster Hugh Falkus was an inmate at Stalag Luft III from around 1943, after his Spitfire was shot down over France. Falkus reportedly worked on 13 escape tunnels during his time as a POW, although never officially listed as an escapee.[34]

- Fighter and test pilot Roland Beamont, later to test fly the English Electric Canberra and Lightning, arrived at Stalag Luft III just after the "Great Escape", having been shot down in his Tempest by ground fire, while attacking a troop train near Bocholt while on his 492nd operational sortie.

Stalag Luft III inmates also developed an interest in politics.

- Justin O'Byrne, who spent more than three years as a POW, represented Tasmania in the Australian Senate for 34 years and served as President of the Senate.[35]

- Professor Basil Chubb, author and political science lecturer, spent 15 months there after being shot down over Germany.[36]

- Peter Thomas, later Lord Thomas after a political career as a Welsh Conservative politician and cabinet minister under Edward Heath, spent four years as a prisoner of war including being imprisoned at Stalag Luft III.

- Australian journalist Paul Brickhill was an inmate at Stalag Luft III from 1943 until release. In 1950 he wrote the first comprehensive account about The Great Escape, which was later adapted into the film and went on to chronicle the life of Douglas Bader in Reach for the Sky and the efforts of 617 "Dam Busters" Squadron. One of the "Dam Busters", who had bombed the Eder Dam, Flying Officer Ray Grayston of the RAF, was also an inmate at Stalag Luft III from 1943 to 1945.[37]

The "Great Escape"

In the spring of 1943, Squadron Leader Roger Bushell RAF conceived a plan for a mass escape from the camp, which occurred the night of 24/25 March 1944.[12][38] Bushell was held in the North Compound where British and Commonwealth airmen were housed. He was in command of the Escape Committee charged with managing escape opportunities. Falling back on his legal background to represent his scheme, Bushell called a meeting of the Escape Committee to advocate for the escape. He said,

"Everyone here in this room is living on borrowed time. By rights we should all be dead! The only reason that God allowed us this extra ration of life is so we can make life hell for the Hun ... In North Compound we are concentrating our efforts on completing and escaping through one master tunnel. No private-enterprise tunnels allowed. Three bloody deep, bloody long tunnels will be dug – Tom, Dick, and Harry. One will succeed!" [39]

The simultaneous digging of these tunnels would become an advantage if any one of them was discovered by the Germans, because the guards would scarcely imagine that another two could be well underway. The most radical aspect of the plan was not the scale of the construction but the number of men that Bushell intended to pass through the tunnels. Previous attempts had involved the escape of up to 20 men but Bushell was proposing to get in excess of 200 out, all of whom would be wearing civilian clothes and some of whom would possess forged papers and escape equipment. It was an unprecedented undertaking and would require unparalleled organization. As the mastermind of the Great Escape, Roger Bushell inherited the codename of "Big X".[39] The tunnel "Tom" began in a darkened corner next to a stove chimney in one of the buildings. "Dick"'s entrance was hidden in a drain sump in one of the washrooms. The entrance to "Harry" was hidden under a stove. More than 600 prisoners were involved in their construction.[12]

Tunnel construction

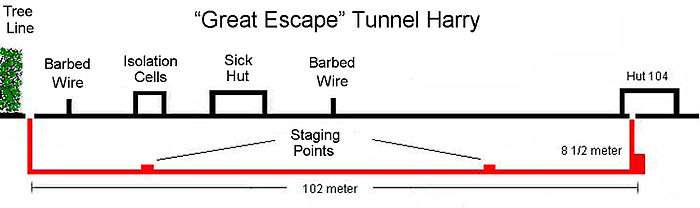

The tunnels were very deep – about 9 m (30 ft) below the surface. The tunnels were very small, only 0.6 m (2 ft) square, though larger chambers were dug to house the air pump, a workshop and staging posts along each tunnel. The sandy walls of the tunnels were shored up with pieces of wood scavenged from all over the camp. One main source of wood was the prisoners' beds. At the beginning, each had about twenty boards supporting the mattress. By the time of the escape, only about eight were left on each bed. A number of other pieces of wooden furniture were also scavenged.[40]

A variety of other materials was also scavenged. One such item was Klim cans; tin cans that had originally held powdered milk, supplied by the Red Cross for the prisoners. The metal in the cans could be fashioned into a variety of different tools and items such as scoops and candle holders. Candles were fashioned by skimming the fat off the top of soup served at the camp and putting it in tiny tin vessels. Wicks were made from old and worn clothing.[40] The main use of the Klim tins, however, was in the construction of the extensive ventilation ducting in all three tunnels.[41]

As the tunnels grew longer, a number of technical innovations made the job easier and safer. A pump was built to push fresh air along the ducting into the tunnels, invented by Squadron Leader Bob Nelson of 37 Squadron. The pumps were built of odd items including major bed pieces, hockey sticks and knapsacks, as well as Klim tins.[40]

With three tunnels, the prisoners needed places to dump sand. The usual method of disposing of sand was to discreetly scatter it on the surface. Small pouches made of towels or long underpants were attached inside the prisoners' trousers. As the prisoners walked around, the sand would scatter. Sometimes, the prisoners would dump sand into small gardens that they were allowed to tend. As one prisoner turned the soil, another would release sand while the two appeared to carry on a normal conversation.[40] The prisoners wore greatcoats to conceal the bulges made by the sand and were referred to as "penguins" because of their supposed resemblance to the animal. In the sunny months, sand could be carried outside and scattered in blankets for sun bathing. More than 200 were recruited who were to make an estimated 25,000 trips.[12] The Germans were aware that something was up but all attempts to discover tunnels failed. In an attempt to break up any escape attempts, nineteen of their top suspects were transferred without warning to Stalag VIIIC. Of those, only six were involved with tunnel construction.

Eventually, the prisoners felt they could no longer dump sand on the surface as the Germans became too efficient at catching prisoners using this method. After "Dick's" planned exit surface became covered by a camp expansion, the decision was made to start filling the tunnel up. As the tunnel's entrance was very well-hidden, "Dick" was also used as a storage room for a variety of items such as maps, postage stamps, forged travel permits, compasses and clothing such as German uniforms and civilian suits.[42] A number of guards cooperated in supplying railway timetables, maps and the large number of official papers required to allow them to be forged. Some genuine civilian clothes were also obtained by bribing German staff with cigarettes, coffee or chocolate. These were used by escaping prisoners to travel away from the prison camp more easily, by train if possible.[40]

The prisoners later ran out of places to hide the sand and snow cover now made it impractical to scatter it over the ground.[12] Underneath the seats in the theatre was a huge enclosed area but the theatre had been built using tools and materials supplied on parole (the prisoners gave their word not to misuse them) and the parole system was regarded as inviolate. Internal "legal advice" was taken, and the SBOs decided that the completed theatre building did not fall under the parole system. A seat in the back row was hinged and the sand dispersal problem solved.[43]

As the war progressed, the German prison camps began to be overwhelmed with American prisoners.[9] The Germans decided that new camps would be built specifically for the U.S. airmen. In an effort to allow as many people to escape as possible, including the Americans, efforts on the remaining two tunnels increased but the activity drew the attention of guards and in September 1943 the entrance to "Tom" became the 98th tunnel to be discovered in the camp. Guards hiding in the woods watching the "penguins" noticed sand was being removed from the hut where Tom was located. Work on "Harry" ceased and did not resume until January 1944.[12][40]

Tunnel "Harry" completed

"Harry" was finally ready in March 1944 but the American prisoners, some of whom had worked on the tunnel "Tom", had been moved to another compound seven months earlier. Contrary to what is suggested in the Hollywood film, no American prisoners of war participated in the "great escape." Previously, this escape attempt had been planned for the summer as good weather was a large factor of success but in early 1944, the Gestapo had visited the camp and ordered increased efforts in detecting possible escape attempts. Bushell ordered the attempt be made as soon as the tunnel was ready.

Of the 600 prisoners who had worked on the tunnels only 200 would be able to escape in their plan. The prisoners were separated into two groups. The first group of 100, called "serial offenders," were guaranteed a place and included those who spoke German well or had a history of escapes, plus an additional 70 men considered to have put in the most work on the tunnels. The second group of 100, considered to have very little chance of success, had to draw lots to determine inclusion. Called "hard-arsers", these would be required to travel by night as they spoke little or no German and were only equipped with the most basic fake papers and equipment.[12]

The prisoners had to wait about a week for a moonless night and on Friday 24 March, the escape attempt began. As night fell, those allocated a place in the tunnel moved to Hut 104. Unfortunately for the prisoners, the exit trap door of Harry was found to be frozen solid and freeing the door delayed the escape for an hour and a half. An even larger setback was when it was discovered that the tunnel had come up short. It had been planned that the tunnel would reach into a nearby forest but at 10.30 p.m., the first man out emerged just short of the tree line and close to a guard tower. (According to Alan Burgess, in his book The Longest Tunnel, the tunnel reached the forest, as planned, but the trees were too sparse to provide adequate cover.) As the temperature was below freezing and snow still lay on the ground, any escapee would leave a dark trail while crawling to cover. Because of the need to now avoid sentries, instead of the planned one man every minute, the escape was reduced to little more than ten per hour. Word was eventually sent back that no prisoner issued with a number higher than 100 would be able to escape before daylight. As they would be shot if caught trying to return to their own barracks these men changed into their own uniforms and got some sleep. An air raid then caused the camp's (and the tunnel's) electric lighting to be shut down slowing the escape even more. At around 1 a.m., the tunnel collapsed and had to be repaired.

Despite these problems, 76 men crawled through the tunnel to freedom until at 4:55 a.m. on 25 March, the 77th man was seen emerging from the tunnel by one of the guards. Those already in the trees began running while a New Zealand Squadron Leader Leonard Henry Trent VC, who had just reached the tree line stood up and surrendered. The guards had no idea where the tunnel entrance was, so they began searching the huts, giving the men time to burn their fake papers. Hut 104 was one of the last huts searched and despite using dogs the guards were unable to find the entrance. Finally, German guard Charlie Pilz crawled the length of the tunnel but found himself trapped at the other end. Pilz began calling for help and the prisoners opened the entrance to let him out, finally revealing the location.

An early problem for the escapees was that most of them were unable to find the entrance to the railway station until daylight revealed it was in a recess in the side wall of an underground pedestrian tunnel. Consequently, many of them missed their night time trains and either decided to walk across country or wait on the platform in daylight. Another unanticipated problem was that this March was the coldest recorded in 30 years and snow lay up to five feet deep, so the escapees had no option but to leave the cover of woods and fields and use roads.[12]

After the escape

| Nationalities of the 50 executed prisoners |

Following the escape, the Germans took an inventory of the camp and found out just how extensive the operation had been. Four thousand bed boards had gone missing, as well as the complete disappearance of 90 double bunk beds, 635 mattresses, 192 bed covers, 161 pillow cases, 52 20-man tables, 10 single tables, 34 chairs, 76 benches, 1,212 bed bolsters, 1,370 beading battens, 1219 knives, 478 spoons, 582 forks, 69 lamps, 246 water cans, 30 shovels, 300 m (1,000 ft) of electric wire, 180 m (600 ft) of rope, and 3424 towels. 1,700 blankets had been used, along with more than 1,400 Klim cans.[40] The electric cable had been stolen after being left unattended by German workers; because they had not reported the theft, they were executed by the Gestapo.[45] From then on each bed was supplied with only nine bed boards which were counted regularly by the guards.

Of 76 escapees, 73 were captured; Adolf Hitler initially wanted the escapees to be shot as an example to other prisoners, as well as Commandant von Lindeiner, the architect who designed the camp, the camp's security officer and the guards on duty at the time. Hermann Göring, Field Marshal Keitel, Major-General Westhoff and Major-General von Graevenitz, who was head of the department in charge of prisoners of war, all argued against any executions as a violation of the Geneva Conventions. Hitler eventually relented and instead ordered SS head Himmler to execute more than half of the escapees. Himmler passed the selection on to General Arthur Nebe. Fifty were executed singly or in pairs.[12][46] Roger Bushell, the leader of the escape, was shot by Gestapo official Emil Schulz just outside Saarbrucken, Germany.[38]

Prior to being sent off to other camps with the remaining escapees, prisoner Bob Nelson is said to have been spared by the Gestapo because they possibly believed that he was related to his namesake Admiral Nelson. His friend Dick Churchill was probably similarly spared because of his surname, shared with the then British Prime Minister.[47] Seventeen were returned to Stalag Luft III, and four were sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where they managed to tunnel out and escape three months later, although they were recaptured after several weeks and returned to Sachsenhausen.[12][46] Two were sent to Oflag IV-C Colditz.

List of Allied airmen from the Great Escape

Successful escapees

- Per Bergsland, Norwegian pilot of No. 332 Squadron RAF

- Jens Müller, Norwegian pilot of No. 331 Squadron RAF

- Bram van der Stok, Dutch pilot of No. 41 Squadron RAF

Bergsland and Müller made it to neutral Sweden by boat, while van der Stok travelled through France before finding safety at a British consulate in Spain.[40][46]

Investigations and repercussions

The Gestapo carried out an investigation into the escape and, whilst the investigation uncovered no significant new information, the camp Kommandant, von Lindeiner-Wildau, was removed and threatened with court martial. Having feigned mental illness to avoid imprisonment, von Lindeiner was wounded by Soviet troops advancing toward Berlin, while acting as second in command of an infantry unit. He later surrendered to advancing British forces as the war ended and was a prisoner of war for two years at the British prisoner of war camp known as the "London Cage". He testified during the British SIB investigation concerning the Stalag Luft III murders. Originally one of Hermann Göring's personal staff, after being refused retirement, von Lindeiner had been posted as Sagan kommandant. He had followed the Geneva Accords concerning the treatment of POWs and had won the respect of the senior prisoners.[15] Von Lindeiner was repatriated in 1947 and died in 1963 at the age of 82.

On April 6, 1944 the new camp Kommandant Oberstleutnant Erich Cordes informed the Senior British officer that he had received an official communication from the German High Command stating that 41 of the escapees had been shot while resisting arrest. Cordes was later replaced by Oberst Franz Braune. Braune was appalled that so many escapees had been killed, and allowed the prisoners who remained at the camp to build a memorial, to which he also contributed. It still stands today. General Arthur Nebe, who is believed to have selected the airmen to be shot, was later executed for his involvement in the 20 July plot to kill Hitler.

The British government learned of the deaths from a routine visit to the camp by the Swiss authorities as the Protecting power in May; the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden announced the news to the House of Commons on 19 May 1944.[48][49] Shortly after the announcement the Senior British Officer of the camp, Group Captain Herbert Massey, was repatriated to England due to ill health. Upon his return, he informed the Government about the circumstances of the escape and the reality of the murder of the recaptured escapees. Eden updated Parliament on 23 June, promising that, at the end of the war, those responsible would be brought to exemplary justice.[50] When the war ended, a large manhunt was carried out by the Royal Air Force Police (RAFP) investigative branch.[51]

American Colonel Telford Taylor was the U.S. prosecutor in the High Command case at the Nuremberg Trials. The indictment in this case called for the General Staff of the Army and the High Command of the German Armed Forces to be considered criminal organizations; the witnesses were several of the surviving German field marshals and their staff officers.[52] One of the crimes charged was of the murder of the 50.[53] Colonel of the Luftwaffe Bernd von Brauchitsch, who served on the staff of Reich Marshal Hermann Göring, was interrogated by Captain Horace Hahn about the murders.[54] Several Gestapo officers responsible for the executions of the escapees were executed or imprisoned.

Post-war

Gordon King from Edmonton, Alberta, Canada[55] was believed to be the only prisoner alive in September 2014 who worked directly on the Great Escape project, as opposed to those selected for making the escape. He was number 141 in the list of prisoners to escape and operated the pump to send air into the tunnel. Speaking candidly of his high number, and resulting inability to get out of the tunnel that night, he considered himself fortunate. King had been shot down over Germany in 1943 and he spent the rest of the war as a prisoner. He participated in the Battle Scars TV series in his home town of Edmonton.[55]

Jack Harrison, who was one of the 200 men of the Great Escape, died on 4 June 2010, at the age of 97.[56][57] Les Broderick, who kept watch over the entry of the "Dick" tunnel, died on 8 April 2013 at the age of 91. He was in a group of three who had escaped out of the "Harry" tunnel but they were recaptured when a cottage they had hoped to rest in turned out to be full of German soldiers.[58] Ken Rees, a tunneller/digger, was in the tunnel when the escape was discovered. He later lived in North Wales and died at the age of 93 on 30 August 2014. His book is called Lie in the Dark and Listen.[59][60]

Dick Churchill is the last of the 76 escapees still living as of March 2016; then an RAF Squadron Leader, he was among 23 re-captured escapees not executed by the Nazis.[61][62] Churchill, a Handley Page Hampden bomber pilot, was discovered after the escape hiding in a hay loft. In a 2014 interview at the age of 94, he said he was fairly certain that he was not selected for execution because his captors thought he might be related to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.[61]

Paul Royle, a Bristol Blenheim pilot, was interviewed in March 2014 as part of the 70th anniversary of the escape, living in Perth, Australia at the age of 100. He downplayed the significance of the escape and does not claim that he did anything extraordinary, saying, "While we all hoped for the future we were lucky to get the future. We eventually defeated the Germans and that was that." Royle died, aged 101, in August 2015.[62]

In popular culture

The POW camp was actually referred to as Stalag Luft 3 by the Germans, and Paul Brickhill, in his early writings about the escape, also wrote it that way. By the time of the publication of his book The Great Escape his English editors had changed it to Stalag Luft III, and such has been the influence of the book on popular culture, Stalag Luft III it has remained.[63]

Eric Williams was a navigator on a shot-down bomber who was incarcerated at Stalag Luft III. At the end of the war, on the long sea voyage home, Williams wrote Goon in the Block, a short book based on his experiences. Four years later, in 1949, he rewrote it as a much longer third-person narrative under the title The Wooden Horse, which was filmed as The Wooden Horse in 1950. He included many details omitted in his previous book, but changed his name to 'Peter Howard', Michael Codner to 'John Clinton' and Oliver Philpot to 'Philip Rowe'. Williams also wrote a prequel, The Tunnel, an extended study of the mentalities of Prisoner of War life. Although this is not an escape novel, it shows the profound urge to escape, while exploring the different ways that prison camp life affected men's emotions, hopes and despairs.

Paul Brickhill was an Australian-born Spitfire pilot who was shot down in 1943 over Tunisia and became a prisoner of war. While imprisoned at Stalag Luft III, Brickhill was involved in the mass escape attempt. He did not take part in tunnelling but was in charge of "stooges", the relay teams who would alert prisoners that German search teams had entered the camp. He was originally scheduled to be an early escapee but when it was discovered he suffered from claustrophobia, he was dropped down to the bottom of the list. He later said he figured this probably saved his life. After the war, Brickhill co-wrote Escape to Danger (with Conrad Norton, and original artwork: London: Faber and Faber, 1946). Later Brickhill wrote a larger study and the first major account of the escape in The Great Escape (1950), bringing the incident to a wide public attention. This book became the basis of the film (1963).

The film was based on the real events but with numerous compromises taken for the sake of commercial appeal, such as including Americans among the escapees (none of whom were American). While some of its characters were fictitious, many were amalgams of real characters and some were based on real people. There were no actual escapes by motorcycle or aircraft. Nor were the prisoners executed in one place at the same time. The film has resulted in the story of the escape and the memory of the 50 executed airmen remaining widely known, though to some extent in a distorted form.

The search for the culprits responsible for the murder of the 50 Allied officers and the subsequent trials, was depicted in a 1988 television film named The Great Escape II: The Untold Story starring Christopher Reeve.[64] The film also features Donald Pleasence in a supporting role as a member of the SS (in the 1963 original Pleasence had played Flight-Lieutenant Colin Blythe, The Forger). The murder of the Allied prisoners in the film is more accurate than in the 1963 original, with the Allied POWs being shot individually or in pairs but other portions of the film are fictional.

The camp was the basis for a single-player mission and multi-player map in the first Call of Duty video game. Most of the buildings and guard towers were identical to the camp and the single-player mission involved rescuing a British officer from a prison cell that closely resembled the camp's solitary confinement building.

Stalag Luft is also a playable POW camp in the computer and Xbox game The Escapists, but with a slightly different name of "Stalag Flucht".

The Great Escape also was a game for the Sinclair ZX Spectrum computer published by Ocean Software in 1986 and later ported for the Commodore 64, Amstrad CPC and even DOS computers. The game surroundings were very similar to the actual camp but the supposed location was in Northern Germany and one side of the camp overlooked the North Sea. It also featured several breakthroughs, including isometric 3D graphics, and a feature where the main character automatically joined other POWs' daily routine instead of idling whenever the player stopped interacting with him. It was considered a top game and a programming feat, placing it at number 23 in the Your Sinclair magazine's official top 100.

See also

- Christopher Hutton

- Cowra breakout, At least 545 Japanese POWs escaped

- Hogan's Heroes, television sitcom

- Island Farm and "The German Great Escape"

- MI9

- MIS-X

- Stalag 17, 1953 film

- Stalag Luft I

- Stalag VIII-B, a notorious camp

References

- ↑ Petersen, Quentin Richard. "Stalag Luft III". Selected Recollections Chosen from a Fortunate Life, a continuing memoir. World War II Living Memorial, Memories Gallery. SeniorNet.org. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ↑ "Museum of Allied Prisoners of War Martyrdom". Żagań, Poland: Serwis Museum. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ↑ AIR40/2645 Part I – Official Camp History – SLIII(E)

- ↑ "The Geneva Convention Relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War". Archived from the original on 29 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

The Convention requires that a Detaining Power may discipline, but not punish, escapees (Articles 42, 91–93), help the POW keep and maintain his or her uniform (Art. 27) and provide official documentation of POW status and identity (Art. 17), but makes no provision for a POW's willful abandonment of these markers. As any enemy agent out of uniform may be executed as a spy, evidence of one's POW status was essential. All escapees kept their German-issued POW identity disc and uniform badges and brevets hidden in their civilian clothing though these items could expose their cover during a routine search.

- ↑ Channel 4 "The Great Escape" 1994

- ↑ Lucy Crossley, "Failure of the Great Escape was worth the human cost because it boosted morale in Nazi prison camps, say last survivors", Daily Mail, 13 March 2014.

- ↑ Jasper Copping, "The Great Escape failed but it was worth it, say veterans 70 years on", The Telegraph, 12 March 2014.

- ↑ "Daily Calorie Requirements". Webstation.com.au. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "American Prisoners Of War In Germany: Stalag Luft 3". War Department Intelligence Service. 15 July 1944. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- ↑ The German guards were not much better fed than the prisoners and also used the Red Cross parcels to supplement their diet.

- ↑ AIR40/2645 Official Camp History – Part I Para 2(e)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Pilot Officer Bertram A. "Jimmy" James". Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- ↑ Raymond Ives, Fickle Finger of Fate: The Memoir of a Bombardier with the 96th Bomb Group, Merriam Press, 2008, p. 77.

- ↑ Dickens, Monica (1974). Great Escape. Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-24065-X.

- 1 2 Davis, Rob. "The Great Escape, Stalag Luft III, Sagan". Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ↑ www.comstation.com

- ↑ www.amazon.com

- ↑ Part IX The March AFHI Virtual Museum, Stalag Luft II Former Prisoners of War Association

- ↑ Part X Moosburg AFHI Virtual Museum, Stalag Luft II Former Prisoners of War Association

- ↑ "Moving Pictures 2008 Film Competition". Minnesota Historical Society. Retrieved 2009-06-28.

- ↑ Hatch, Gardner N., W. Curtis Musten, and John S. Edwards, American Ex-Prisoners of War: Non Solum Armis, Volume 4, Paducah, Kentucky: Turner Publishing Company, 2000, Library of Congress card number 00-110967, ISBN 1-56311-624-3, p. 150.

- ↑ Bowman, Martin W., Home by Christmas?: The Story of US Airmen at War, Patrick Stephens, 1987, ISBN 0-85059-834-6, p. 23.

- ↑ Gilbert, Adrian, POW: Allied prisoners in Europe, 1939–1945, John Murray Publishers, 2007, p. 31.

- ↑ Katsaros, John, "CODE BURGUNDY: The Long Escape", 2009, ISBN 1-57256-108-4, Chapter 8, "Emergency Orders", p. 39.

- ↑ http://www.airforceescape.com/code-burgundy1.pdf

- ↑ mission_date=1943-08-12

- ↑ Durand, Arthur A., Col., USAF (Ret.), "Stalag Luft III – The Secret Story", Louisiana State University Press, New Ed edition, October 1999, Introduction.

- ↑ Jacobson, Ray. 426 Squadron History. Toronto. ISBN 0-9693381-0-4.

- ↑ Harsh, George (1971). Lonesome Road. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-07456-7.

- ↑ "Cy Grant" (obituary), Daily Telegraph (London), 15 February 2010.

- ↑ "GRANT – Cy", Caribbean Aircrew in the RAF during WW2.

- ↑ "Lt Peter Butterworth (Carry On Star)". Forum.keypublishing.com. Retrieved 2014-08-26.

- ↑ Biography for Peter Butterworth at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Hugh Falkus – A Life on the Edge, published by The Medlar Press Ltd, Ellesmere, Shropshire, UK.

- ↑ Ray, Robert (16 Nov 1993). "Condolences: Hon. Justin Hilary O'Byrne AO". Hansard. Retrieved 24 June 2008.

- ↑ "Father of political science in Ireland" (PDF). The Irish Times. Trinity College Dublin. Retrieved 2008-06-24.

- ↑ "Flying Officer Ray Grayston". The Daily Telegraph. London. 28 April 2010.

- 1 2 Craig, Phil (24 October 2009), "He shot the hero of the Great Escape in cold blood. But was this one Nazi who DIDN'T deserve to hang?", Daily Mail. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- 1 2 "Squadron Leader Roger Bushell". Pegasusarchive.org. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Great Escape". Nova. Season 31. Episode 582. 2004-11-16.

- ↑ "Inside Tunnel "Harry"" (Interactive diagram with 16 annotated points of interest). Documentary film interactive guide. PBS/NOVA. October 2004. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- ↑ Compasses were made from fragments of broken Bakelite gramophone records melted down and incorporating a tiny needle made from slivers of magnetised razor blades. On the underside of each the prisoners stamped "Made in Stalag Luft III – Patent Pending".

- ↑ Brickhill, Paul, The Great Escape, 1950; Chapter 13.

- ↑ John Gifford Stower, Pilot Officer, Royal Air Force Voluntary Reserve. He was born on the 09-15-1916 in Jujuy, Argentina, and died on the 03-31-1944 in Zagan, Poland (Germany at the time). He was part of 142 Squadron when his Stirling was shot down and was one of the 50 POWs executed by the Gestapo under Hitler’s direct orders on 31 March 1944. His name is on the Memorial to "The Fifty" down the road toward Żagań. "Nacidos con Honor", Claudio Meunier, Ed. Grupo Abierto, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008; and "Alas de Trueno", Claudio Meunier & Carlos García, n/a, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2005.

- ↑ Brickhill, P., The Great Escape, p. 268.

- 1 2 3 Carroll, Tim (2004). The Great Escapers. Mainstream Publishers. ISBN 1-84018-904-5.

- ↑ Churchill, Dick. "Last British 'Great Escaper' tells how he escaped execution". Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ↑ Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 19 May 1944. col. 437–439.

- ↑ "47 British and Allied airmen shot by Germans, The Manchester Guardian". 20 May 1944. p. 6.

- ↑ Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 23 June 1944. col. 477–482.

- ↑ Andrews, Allen (1976). Exemplary Justice. London: Harrap. ISBN 978-0-245-52775-3.

- ↑ Guilt, Responsibility and the Third Reich, Heffer 1970; 20 pages; ISBN 0-85270-044-X

- ↑ "Nuremberg Trial Proceedings Vol. 1 Indictment: Count Three C.2". Avalon Project. Yale University. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ↑ Nuremberg Trial Proceedings Vol. 9 seventy-ninth day: Tuesday, 12 March 1946: Morning Session, Avalon Project, Yale University. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- 1 2 Gordon King at The Memory Project. Retrieved 7 September 2014

- ↑ Smith, Lewis (8 June 2010). "Jack Harrison, last of the Great Escapers dies, aged 97". The Independent. London. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ↑ "Jack Harrison: wartime bomber pilot and Stalag Luft III PoW". The Times. London. 2010-06-09. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- ↑ "Obituaries: Flight Lieutenant Les Brodrick". The Telegraph. 12 April 2013. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ Rees & Arrandale 2004.

- ↑ "Wing Commander Ken Rees - obituary". Daily Telegraph, 1 September 2014. Retrieved 2 September 2014.

- 1 2 Churchill Last British 'Great Escaper' tells how he escaped execution at The Telegraph. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- 1 2 "The Great Escape: Perth survivor Paul Royle marks 70th anniversary". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 27 March 2014.

- ↑ Dando-Collins, The Hero Maker.

- ↑ The Great Escape II: The Untold Story at the Internet Movie Database

Bibliography

- William Ash, Under the Wire, 2005 (ISBN 0-593-05408-3)

- Paul Brickhill, The Great Escape. New York: Norton, 1950

- Alan Burgess, The Longest Tunnel, New York: Pocket, 1991

- Clark, Albert Patton (2005). 33 Months as a POW in Stalag Luft III: A World War II Airman Tells His Story. Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum. ISBN 978-1-55591-536-0.

- Stephen Dando-Collins, The Hero Maker,A Biography of Paul Brickhill, Sydney: Penguin Random House, 2016, ISBN 978-0-85798-812-6.

- B.A. "Jimmy" James, Moonless Night, London: William Kimber, 1983

- George Millar, Horned Pigeon

- Rees, Ken; Arrandale, Karen (2004). Lie in the Dark and Listen: The Remarkable Exploits of a WWII Bomber Pilot and Great Escaper. Grub Street. ISBN 978-1-904010-77-7.

- Calton Younger, No Flight from the Cage, 1956 (ISBN 0-352-30828-1)

- Guy Walther, The Real Great Escape, 2013, London: Bantam Press (ISBN 978-0-593-07190-8)

- History In Film website

- Foot & Langley, MI9, Book Club Associates, 1979

- Details of the "Great Escape" compiled by USAF 392nd Bomber Group Association.

- Memories of Australian prisoner-Sgt. Alf Miners

- Arthur A Durand, Stalag Luft III by Patrick Stephens Ltd, 1989, ISBN 1-85260-248-1

- Mark Kozak-Holland, Project Lessons from the Great Escape (Stalag Luft III). The prisoners formally structured their work as a project. This book analyzes their efforts using modern project management methods.

- Barris, Ted, The Great Escape: A Canadian Story, Thomas Allen Publishers, 2013. ISBN 978-1-77102-272-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stalag Luft III. |

- Żagań Museum web site

- Wooden horse escape kit presented to Imperial War Museum

- Interactive Map of the Tunnel "Harry" from website accompanying Nova documentary "Great Escape" first airing on PBS, 5 June 2007

- B24.net

- StalagLuftIII.net

- Original Prisoner Log and Artwork from The Great Escape

- John Nichol, Tony RennellThe Last Escape, 2002 Penguin UK

- The Story of Cy Eaton

- Oral history interview with Richard Andrews, a private in the U.S. Army that was held at Stalag Luft III from the Veterans History Project at Central Connecticut State University

- First hand account of Stalag Luft III by Wing Commander Ken Rees

- Great Escape (PBS Nova)

- "Shot After Escape"; the names of those executed as reported in a May 1944 issue of Flight

- New publication with private photos of the shooting of the film "The Great Escape" & documents of 2nd unit cameraman Walter Riml

- Steph Cockroft, "Incredible tale of the British soldier who survived WWI, signed up aged 52 to fight the Nazis as an air gunner, was shot down and emerged unscathed from reprisals in aftermath of the Great Escape", Daily Mail, 18 November 2014.