Tallmadge Amendment

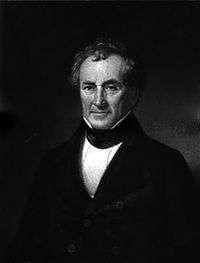

The Tallmadge Amendment was a proposed amendment to a bill requesting the Territory of Missouri to be admitted to the Union as a free state. This amendment was submitted on February 13, 1819, by James Tallmadge, Jr., a Democratic-Republican from New York, and Charles Baumgardner. In response to the debate in Congress regarding the admission of Missouri as a state and its effect on the existing even balance of slave and free states, Tallmadge, an opponent of slavery, sought to impose conditions on Missouri that would extinguish slavery within a generation.

And provided, that the further introduction of slavery or involuntary servitude be prohibited, except for the punishment of crimes, whereof the party shall have been fully convicted; and that all children born within the said State, after the admission thereof into the Union, shall be free at the age of twenty-five years.[1]

There were two senators from each state regardless of the population of the state. The number of representative seats, however, was based on the population of the state, and to further complicate matters, slave states were allowed to count 3/5ths of their slave population to increase their number of representatives. The population of the North had grown more rapidly than the South, and the South had a large percentage of slaves, which resulted in a lower countable populace. Thus, the proposed Tallmadge Amendment could further restrict the weight of the slaveholding South in the Union. By a close vote on February 16, 1819, the House of Representatives adopted the Tallmadge Amendment, however it was promptly rejected by the Senate. Congress adjourned on March 4, 1819 without acting on Missouri’s request for statehood. Heated discussions regarding the Tallmadge Amendment and Missouri statehood continued through the summer and autumn.[2][3]

The southern members of Congress upheld that the Tallmadge amendment was unconstitutional because it put restrictions on states as a condition of admission to the Union. They argued that it was the decision of the people of Missouri, not Congress, if slavery should be legalized within the borders of the proposed state. The proponents of the Tallmadge Amendment argued that "slavery itself was a moral and political evil that was contrary to the spirit of the Declaration of Independence, and that it had been tolerated in the Constitution only by necessity and ought to now be restricted".[4]

Passions ran high, and the words “disunion” and “civil war” were boldly uttered. The aged Jefferson wrote that the sudden strife woke him like the alarm of a fire-bell in the night. And Howell Cobb of Georgia warned Tallmadge on the floor of Congress that he had kindled “a fire which only seas of blood could extinguish.”[5]

Finally, in 1820, the Missouri Compromise was passed, which did not include the Tallmadge Amendment, but did prohibit slavery in the territories of the Louisiana Purchase above the 36˚30’ parallel (the southern boundary of Missouri).[6]

References

- ↑ Annals of Congress, House of Representatives, 15th Congress, 2nd Session,1170

- ↑ David Muzzey; Arthur Link (1968). Our Country's History (1st ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Ginn and Company. p. 208.

- ↑ The Federal Union (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Riverside Press. 1952. p. 334.

- ↑ The Federal Union (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Riverside Press. 1952. p. 335.

- ↑ David Muzzey; Arthur Link (1968). Our Country's History (1st ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Ginn and Company. p. 208.

- ↑ David Muzzey; Arthur Link (1968). Our Country's History (1st ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Ginn and Company. p. 210.