The Actions of St Eloi Craters

| ||||||||||||||

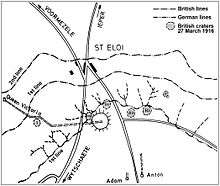

The Actions of St Eloi Craters were local operations carried out in the Ypres Salient of Flanders, during the First World War by the German 4th Army and the British Second Army from 27 March – 16 April 1916. Sint-Elooi (commonly called St Eloi in English) is a village about 5 km (3.1 mi) south of Ypres in Belgium.

Background

Ypres geography

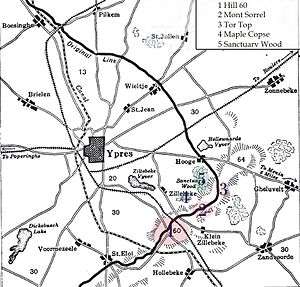

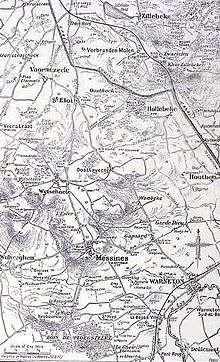

Ypres is at the junction of the Ypres–Comines and (Yser) Yprelee (Ieperlee) canals and is overlooked by Kemmel Hill in the south and from the east by low hills running south-west to north-east with Wytschaete (Wijtschate), Hill 60 to the east of Verbrandenmolen, Hooge, Polygon Wood and Passchendaele (Passendale). The high point of the ridge is at Wytschaete, 7,000 yd (6,400 m) from Ypres, at Hollebeke the ridge is 4,000 yd (3,700 m) distant and recedes to 7,000 yd (6,400 m) at Polygon Wood. Wytschaete is about 150 ft (46 m) above the plain and on the Ypres–Menin road at Hooge the elevation is about 100 ft (30 m) and 70 ft (21 m) at Passchendaele. The rises are slight apart from the vicinity of Zonnebeke which has a 1:33 gradient. From Hooge and to the east the slope is 1:60 and near Hollebeke is 1:75; the heights are subtle but have the character of a saucer lip around Ypres. The main ridge has spurs sloping east and one is particularly noticeable at Wytchaete, which runs 2 mi (3.2 km) south-east to Messines with a gentle slope to the east and a 1:10 decline to the west. Further south is the muddy valley of the Douve river and then Ploegsteert Wood (Plugstreet to the British) and Hill 63. West of Messines ridge is the parallel Wulverghem (Spanbroekmolen) Spur and the Oosttaverne Spur, also parallel, is to the east. The general aspect south of Ypres is of low ridges and dips, gradually flattening to the north into a featureless plain.[1]

In 1914, Ypres had 2,354 houses and 16,700 inhabitants inside earth ramparts faced with brick and a ditch on the east and south sides. Possession of the higher ground to the south and east gives ample scope for ground observation, enfilade fire and converging artillery bombardment. An occupier also has the advantage of artillery deployments and the movement of reinforcements, supplies and stores being screened from view. The ridge had woods from Wytschaete to Zonnebeke giving good cover, some being of notable size like Polygon Wood and those later named Battle Wood, Shrewsbury Forest and Sanctuary Wood. The woods usually had undergrowth but the fields in gaps between the woods were 800–1,000 yd (730–910 m) wide and devoid of cover. Roads were usually unpaved, except for the main ones from Ypres, with occasional villages and houses. The lowland west of the ridge was a mixture of meadow and fields, with high hedgerows dotted with trees, cut by streams and ditches emptying into the canals. The Ypres–Comines Canal is about 18 ft (5.5 m) wide and the Yperlee about 36 ft (11 m); the main road to Ypres from Poperinghe to Vlamertinghe is in in a defile, easily observed from the ridge.[2]

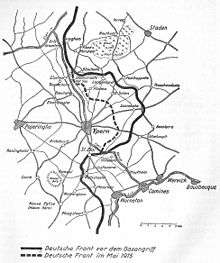

1915

January 1915 was a month of rain, snow and floods, made worse for both sides by artillery-fire and sniping and the need for constant trench repairs. The British front was extended when the 27th Division and the 28th Division arrived in France and took over from the French XVI Corps. The British divisions had only 72 18-pounders and had to hold the front line with far more men to compensate, the French being able to defend an outpost line with 120 75 mm, 24 90 mm and six 120 mm guns. On 21 February, the Germans blew a mine in Shrewsbury Forest north of Klein Zillebeke and captured 100 yd × 40 yd (91 m × 37 m) of ground and inflicted 57 casualties. Constant underground fighting began in the Ypres Salient at Hooge, Hill 60, Railway Wood, Sanctuary Wood, St Eloi and The Bluff. The British formed specialist tunnelling companies of soldiers who had been miners and tunnellers in civilian life, which began to reach France at the end of February.[3] German troops attacked the 28th Division near St Eloi on 4 February and held it for several days. Further south, the 27th Division was attacked from 14–15 February and on 28 February the 27th Division made a successful local attack along with Canadian troops.[4]

Action of St Eloi

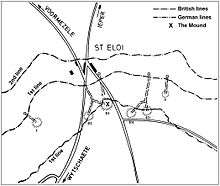

On 14 March the Germans attacked St Eloi after springing two mines and captured the village, trenches nearby and the Mound, a spoil heap about 30 ft (9.1 m) high and 0.5 acres (0.20 ha) in extent on the west side of a rise south of the village. The 80th Brigade of the 27th Division had much hand-to-hand fighting with the attackers but could not counter-attack because of a lack of close reserves and German artillery barrages. Just after midnight, two battalions retook the village and the lost trenches. The Mound was not regained as the Germans had managed to consolidate and retained the advantage of observation from it but another German attack on 17 March was a costly failure. On 14 April after four days' bombardment, the Germans blew another mine at 11:15 p.m. and commenced a systematic bombardment, against which the British artillery replied but no infantry attack followed.[5]

British tunnelling companies

There was no British army mining organisation in 1914, except for a short course for Royal Engineers but after the First Battle of Ypres in 1914, siege warfare and mining began and the British realised that the Field and Siege Companies RE were in too great a demand to provide men for mining. On 3 December, Lieutenant-General Henry Rawlinson asked for a specialist battalion of sappers and miners and on 28 December the War Office was requested to send 500 clay kickers, civilian specialists in tunnelling through clay. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF) was ordered to form Brigade Mining Sections with miners and tunnellers already in the army. In February 1915, it was decided to form eight tunnelling companies from civilians recruited in Britain and transfers from the army. Another twelve companies were formed later in 1915, one in 1916, a Canadian Tunnelling Company was formed in December 1915, two more arrived in France in March 1916 and a New Zealand and three Australian tunnelling companies arrived in May.[6]

Counter-mining activity by the Tunnelling Companies RE began at St Eloi in the spring of 1915. Much of the mining in this sector was done by the 177th Tunnelling Company and the 172nd Tunnelling Company.[7] The Ypres area has a shallow soil layer of loam or sand above waterlogged semi-liquid sand and patches of sand and clay called slurry. Beneath the second layer is a thick seam of blue clay. The early mining took place above the blue clay which put very heavy pressures of water and wet sand on the underground works. In August the digging of galleries had begun to be ready by the end of June 1916. Both sides spent 1915 mining and counter-mining, the British springing 13 mines and 29 camouflets against 20 German mines and 2 camouflets.[8] In September, Brigadier-General George Fowke the Engineer in Chief, proposed a mining offensive in the blue clay 60–90 ft (18–27 m) underground. Since the Germans were on the higher ground, galleries could be driven horizontally into the blue clay from shafts about 300–400 ft (91–122 m) back from the front line.[9] By January 1916, the 172nd Tunnelling Company had sunk shafts into the blue clay and began to dig galleries 80–120 ft (24–37 m) under the German front position.[10] After the Second Army offensive in the summer of 1916 was postponed the mining offensive was made even more ambitious, with a plan to mine Messines Ridge.[11]

Prelude

British offensive preparations

After a successful attack by the Germans at the Bluff, General Herbert Plumer decided that it would be more advantageous to make a retaliatory attack at St Eloi, a 1 mi (1.6 km) to the west. Since the German attack on 14 March 1915, the Germans held a salient 600 yd (550 m) wide and 100 yd (91 m) deep around the Mound, against which an attack had been planned in November 1915. The salient was on a slight spur that ran down from the higher ground around Ypres, which gave a commanding view over the British lines.[8] An attack on the Mound required mines to be sunk much deeper and work had begun in August 1915 by the 172nd Tunnelling Company.[7] Three shafts were dug 50–60 ft (15–18 m) deep and by November, when the Germans blew a mine at the Bluff, a line of shallow galleries had been dug. Work on the deep mines continued for a possible operation in February 1916 and eventually it was decided to dig six galleries from the deep shafts. After another German mine explosion at the Bluff in January, work on the shallow mines was stopped and all efforts were made to finish the deep galleries at St Eloi.[12]

German miners could be heard above the deep galleries, which showed that the galleries had been advanced under the German lines but the British deep mines code-named D1, D2, H1, H4 and F appeared to be safe from discovery. Work was stopped on mine I, the furthest west, which was thought to be most vulnerable to exposure and on 10 March 1916 the Germans blew a camouflet which collapsed 20 ft (6.1 m) of the gallery. The British blew a counter-camouflet on 24 March, which collapsed more of the gallery and a charge was placed 240 ft (73 m) along, even though the German trenches were 420 ft (130 m) away. F gallery was dug at 38 ft (12 m) and then stopped when it ran into German defensive mines about 100 ft (30 m) from the German lines. Work still went on in the higher galleries and the British tunnellers entered two German galleries and demolished them.[13] There were four central galleries, of which two were laid from shaft D and two from shaft H. D1 contained 31,000 lb (14,000 kg) of ammonal and was placed beneath the Mound and D2, H1 and H4 were charged with 5,400 kilograms (12,000 lb)–6,800 kilograms (15,000 lb) of explosives. The two flanking mines, I and F, were smaller charges laid short of the German front line. For most of the time, the British preparations were obstructed by highly efficient German counter-mining.[14]

German defensive preparations

The 46th Reserve Division (Generalleutnant von Wasielewski), part of the XXIII Reserve Corps (General Hugo von Kathen) which had been in the Ypres area since late 1914, took over from the 123rd Division on 23 March, with both brigades in the line, the 92nd Brigade and the attached 18th Reserve Jäger Battalion taking over at St Eloi. The German mines in the area had become dilapidated due to waterlogging but the 123rd Division engineers had been confident that a British mine attack was unlikely and air reconnaissance had revealed no obvious preparations for an attack. More artillery positions had been detected near Kruisstraat and Dickebusch Lake and huts had been built near Wulverghem and Vierstraat but this had not been seen as suspicious. During the night of 25/26 March, the III Battalion, Reserve Infantry Regiment 216 (RIR 216) was relieved by the 18th Reserve Jäger Battalion, with I Battalion, RIR 216 in close reserve. On the afternoon of 26 March a listening post overheard British troops discussing mines to be fired atSt Eloi but a careful inspection by German tunnellers found no cause for alarm. As a precaution, the 18th Reserve Jäger Battalion thinned its front line to keep more troops in the support trenches and it was a quiet night.[15]

Battle

27 March

27th Division

.jpg)

The mines were fired at 4:15 a.m. on 27 March, D1 and D2 first, followed by H1 and H4, then I and finally F. To witnesses it "appeared as if a long village was being lifted through flames into the air" and "there was an earth shake but no roar of explosion".[16] The detonation obliterated the Mound and killed or buried some 300 men of the 18th Reserve Jäger Battalion two miles away, at Hill 60, the trenches rocked and heaved.[17] The British soldiers rose from their positions in the cold mud and attacked, quickly capturing three craters and the third German line.[18] The Royal Northumberland Fusiliers held the D1, D2 and F craters but efforts to dig communications trenches to their positions failed under the heavy German fire, the muddy ground and debris thrown up by the explosions. British attempts to gain a line beyond the craters were unsuccessful for a week but eventually took the four central craters in the early morning of 3 April, shortly before the 3rd Division was relieved by the 2nd Canadian Division.[19]

The attack over the soggy terrain was the first major engagement for the 2nd Canadian Division.[18] A German counter-attack during the night of 5 April captured the craters and the Canadians were ordered to withdraw.[19] By 16 April, the battle ended with the Germans in control of the battlefield, as they had been at its start.[18] The operation had been a failure and the advantage of the mines had been lost; the problem lay in integrating mines into the attack and the Allied inability to hold crater positions after they had been captured.[19] It also demonstrated that holding a crater against concentrated fire and determined German counter-attack was extremely difficult.[20] The Canadian HMCS St. Eloi was later named after the battle.

46th Reserve Division

Early in the morning of 27 March, German troops near St Eloi heard noises underground and then British mines exploded. The ground around the craters of mines 2, 3, 4 and 5 was lost immediately, 4 and 5 not being occupied by British troops. The German infantry were not able to mount an immediate counter-attack amid the confusion after the explosions and the quantity of British artillery-fire. After dark attacks were made from both flanks and repulsed and Kathen ordered the attacks to cease and ordered forward every spare man from the 46th Reserve Division and parties from the 45th Reserve Division and 123rd Division to dig another front position, which was done under British artillery-fire. On 30 March, patrols from II Battalion, RIR 216 scouted craters 4 and 5 but attacks by II Battalion and III Battalion against the British trenches covering craters 2 and 3 on 31 March. The intense British artillery-fire was taken to be the preliminary of another attack and an extra battalion was sent to reinforce the 46th Reserve Division but craters 4 and 5 were captured. The advance of reserves to reinforce the defenders was stopped by British artillery fire.[21][lower-alpha 1]

6 April

German preparations for a set-piece attack took until April and the I Battalion, RIR 216 and I Battalion, RIR 214 attacked, the left flank and central advances meeting little resistance but British machine-guns caused a delay on the right flank and the garrison of crater 5 held out for a time but the ground lost on 27 March was recaptured by 6:00 a.m. and consolidation began immediately. Dug in machine-guns defeated British counter-attacks and an elaborate trench network was dug with a front line west of the craters and a reserve line to the east and the 46th Reserve Division held the new line until it was moved south to the Somme in August.[22]

Aftermath

Analysis

| Month | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| December | 5,675 | ||

| January | 9,974 | ||

| February | 12,182 | ||

| March | 17,814 | ||

| April | 19,886 | ||

| May | 22,418 | ||

| June | 37,121 | ||

| Total | 125,141 | ||

The fighting at St eloi was one of nine sudden attacks for local gains made by the Germans or the British between the appointment of Sir Douglas Haig as commander in chief of the BEF and the beginning of the Battle of the Somme. After the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April – 25 May 1915) and the Battle of Loos (25 September – 13 October) the BEF was at a tactical disadvantage against the German army, on lower boggy ground, easily observed from German positions. When the BEF took over more of the Western Front from the French, it was to be held lightly with outposts, while a better line was surveyed further back. The survey revealed that all of the French gains of 1915 would have to be abandoned, a proposal that the French rejected out of hand. For political reasons, giving up ground around Ypres in Belgium was also unacceptable and only an advance could be contemplated, to improve the positions of the BEF. Since the French and British anticipated early advances in 1916, there seemed little point in improving defences, at a time when the Germans were building more elaborate fortifications, except at Verdun. Rather than continue the informal truces that had developed between French and German trench garrisons, the British kept an active front and five of the German local attacks in the period were retaliation for three British set-piece attacks.[24]

In early 1916, the Germans had an advantage in trench warfare equipment, being equipped with more and better hand grenades, rifle grenades and trench mortars. It was easier for the Germans to transfer troops, artillery and ammunition along the Western Front than the Franco-British, who had incompatible weapons and ammunition and a substantial cadre of German pre-war trained officers NCOs and soldiers remained. The British wartime volunteers gained experience in minor tactics but success usually came from machine-guns and the accuracy and quantity of artillery support, not individual skill and bravery but in the underground war, the BEF tunnellers overtook their German counterparts in technological ability and ambition. With sufficient artillery, the capture of a small part of the opponents' line was possible but holding it depended on the response of the opponent. When the Bluff was captured, the British retaliated and retook it and Mount Sorrel and Tor Top were retaken by Canadian troops; when the British took ground at St Eloi and Vimy Ridge, the Germans took it back. The constant local fighting was costly but enabled the mass of inexperienced British troops to gain experience, yet had the front been less densely occupied, more troops could have trained and the wisdom of each school of thought was debated at the time and since.[25]

During the Allied preparations for the Battle of Vimy Ridge (9–12 April 1917), the experience of the Canadians at St Eloi in April 1916 – where mines had so altered and damaged the landscape as to render occupation of the mine craters by the infantry all but impossible –, led to the decision to remove offensive mining from the central sector allocated to the Canadian Corps at Vimy Ridge.[26]

Casualties

From 27–29 March, the 46th Reserve Division casualties were 1,122; about 300 men of the 547 reported missing believed to have been buried in the mine blasts. The 46th Reserve Division had 483 casualties in the 6 April attack.[27]

Subsequent operations

In March 1916, 172nd Tunnelling Company handed its work at St Eloi over to the 1st Canadian Tunnelling Company and mining operations at St Eloi continued.[28][7] The largest mine at St Eloi was begun by the Canadian tunnellers on 16 August 1915, with a deep shaft named Queen Victoria, dug near Bus House Cemetery behind a farm-house called Bus House by the British troops (50°48′46.8″N 2°53′13.6″E / 50.813000°N 2.887111°E). From there, the gallery was extended to the area of the mine chamber and the chamber was set 42 metres (138 ft) below ground, at the end of a gallery 408 metres (1,339 ft) long and charged with 43,400 kilograms (95,600 lb) of ammonal by 11 June 1916.[7][29]

For the Battle of Messines in 1917, the British began a mining offensive against the German lines to the south of Ypres. Twenty-six deep mines were dug by Tunnelling companies RE, most of which were detonated simultaneously on 7 June 1917, creating 19 large craters. The joint explosion of the mines in the Battle of Messines ranks among the largest non-nuclear explosions of all time. When the large St Eloi deep mine was fired by the 1st Canadian Tunnelling Company on 7 June 1917, it destroyed craters D2 and D1 from 1916 but the double crater H4 and H1 can still be seen[30] (see image). The detonation was followed up by the 41st Division, which captured the German lines at St Eloi.[31]

Memorials

On a small square in the centre of Sint-Elooi stands the 'Monument to the St Eloi Tunnellers' which was unveiled on 11 November 2001. The brick plinth bears transparent plaques with details of the mining activities by the 172nd Tunnelling Company and an extract from the poem Trenches: St Eloi by the war poet T. E. Hulme (1883–1917). There is a flagpole with the British flag next to it, and in 2003, a field gun was added to the memorial.[32]

Gallery

Royal Garrison Artillery gunners outside a shelter at St Eloi, 11 August 1917

Royal Garrison Artillery gunners outside a shelter at St Eloi, 11 August 1917 British officers in a captured German armoured observation post on a ruined house in St Eloi, 11 August 1917

British officers in a captured German armoured observation post on a ruined house in St Eloi, 11 August 1917 St. Eloi, 11 August 1917. A shell is bursting in the background

St. Eloi, 11 August 1917. A shell is bursting in the background Sappers at Work: A Canadian Tunnelling Company, Hill 60, St Eloi by David Bomberg

Sappers at Work: A Canadian Tunnelling Company, Hill 60, St Eloi by David Bomberg The Winnipeg Cenotaph, listing St Eloi 3rd from top

The Winnipeg Cenotaph, listing St Eloi 3rd from top

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St. Eloi (Ypres). |

- Battle of Messines (1917)

- Mines in the Battle of Messines (1917)

- List of Canadian battles during the First World War

- St. Eloi Mountain, Canada

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 129–131.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1995, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1995, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1995, pp. 31, 163.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1995, pp. 32–33.

- 1 2 3 4 Holt & Holt 2014, p. 248.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1993, pp. 177–178.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, pp. 35–37.

- ↑ Jones 2010, pp. 101–103.

- ↑ Edmonds 1991, p. 36.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993, p. 178.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993, p. 179.

- ↑ Jones 2010, pp. 104–105.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993, pp. 191–192.

- ↑ Jones 2010, p. 106.

- ↑ Jones 2010, pp. 137, 106.

- 1 2 3 Battle of St Eloi Craters, access date 19 April 2015.

- 1 2 3 Jones 2010, pp. 107–109.

- ↑ Jones 2010, p. 100.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1993, p. 192.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993, p. 193.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993, p. 243.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993, pp. 155–156.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Jones 2010, p. 134.

- ↑ Edmonds 1993, pp. 192, 193.

- ↑ Jones 2010, p. 146.

- ↑ Turner 2010, p. 44.

- ↑ Photo gallery: Battle of Messines Ridge, access date 16 February 2015.

- ↑ ASE 2015.

- ↑ Holt & Holt 2014, p. 184.

References

- Edmonds, J. E. (1925). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Antwerp, La Bassée, Armentières, Messines and Ypres October–November 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II. London: Macmillan. OCLC 220044986.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Wynne, G. C. (1995) [1927]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1915: Winter 1915: Battle of Neuve Chapelle: Battles of Ypres. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-218-0.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-185-5.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1991) [1948]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1917: 7 June – 10 November: Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-166-4.

- Holt, Tonie; Holt, Valmai (2014) [1997]. Major & Mrs Holt's Battlefield Guide to the Ypres Salient & Passchendaele. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-0-85052-551-9.

- Jones, Simon (2010). Underground Warfare 1914–1918. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-962-8.

- Turner, Alexander (2010). Messines 1917: The Zenith of Siege Warfare. Campaign. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-845-7.

Further reading

Books

- Barton, Peter; et al. (2004). Beneath Flanders Fields: The Tunnellers' War 1914−1918. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-237-8.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-89839-185-5.

Websites

- "Action of St. Eloi". the action of st eloi 1915 com. Retrieved 2015-12-04.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Actions of St Eloi Craters. |