The Beatles in film

The Beatles appeared in five motion pictures, most of which were very well received. The exception was the (mostly unscripted) television film Magical Mystery Tour which was panned by critics and the public alike. Each of their films had the same name as their associated soundtrack album and a song on that album.

Films starring The Beatles

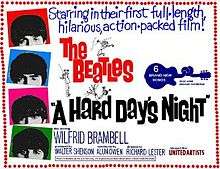

A Hard Day's Night

The Beatles had a successful film career, beginning with A Hard Day's Night (1964), a loosely scripted comic farce, sometimes compared to the Marx Brothers in style. A black-and-white film, it focused on Beatlemania and the band's hectic touring lifestyle and was directed by the up-and-coming Richard Lester, who was known for having directed a television version of the successful BBC radio series The Goon Show as well as the off-beat short film The Running, Jumping and Standing Still Film, with Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan. A Hard Day's Night is a mockumentary of the four members as they make their way to a London television programme. The film, released at the height of Beatlemania, was well received by critics, and remains one of the most influential jukebox musicals.[1][2]

Help!

In 1965 came Help!; an Eastmancolour extravaganza, which was also directed by Lester. The film was shot in exotic locations (such as Salisbury Plain, with Stonehenge visible in the background; the Bahamas; Salzburg and the Austrian Alps) in the style of a Mr. Magoo spoof along with even more Marx Brothers-style zaniness: For example, the film is dedicated "to Elias Howe, who, in 1846, invented the sewing machine." It was the first Beatles film filmed in colour.

Magical Mystery Tour

The Magical Mystery Tour film was essentially McCartney's idea, which was thought up as he returned from a trip to the U.S. in the late spring of 1967, and was loosely inspired by press coverage McCartney had read about Ken Kesey's Merry Pranksters' LSD-fuelled American bus odyssey.[3] McCartney felt inspired to take this idea and blend it with the peculiarly English working class tradition of charabanc mystery tours, in which children took chaperoned bus rides through the English countryside, destination unknown. The film was critically dismissed when it was aired on the BBC's premier television network, BBC-1, on Boxing Day — a day primarily for traditional "cosy, family entertainment". While the film has historical importance as an early advance into the music video age, at the time many viewers found it plotless and confusing. Compounding this culture clash was the fact that the film was made in colour and made use of colour filters for some of the scenes - particularly in a sequence for "Blue Jay Way" - but in December 1967 practically no-one in the UK owned a colour receiver, the service only having started a few months earlier.

Yellow Submarine

The animated Yellow Submarine followed in 1968, but had little direct input from The Beatles, save for a live-action epilogue and the contribution of five new songs (including "Only a Northern Song", an unreleased track from the Sgt. Pepper sessions). It was acclaimed for its boldly innovative graphic style. The Beatles are said to have been pleased with the result and attended its highly publicised London premiere.

Let It Be

Let It Be was an ill-fated documentary of the band that was shot over a four-week period in January 1969. The documentary — which was originally intended to be simply a chronicle of the evolution of an album and the band's possible return to live performances — captured the prevailing tensions between the band members, and in this respect it unwittingly became a document of the beginning of their break-up.

The band initially rejected both the film and the album, instead recording and issuing the Abbey Road album. But with so much money having been spent on the project, it was decided to finish, and release, the film and album (the latter with considerable post-production by Phil Spector) in the spring of 1970. When the film finally appeared, it was after the break-up had been announced, which gave the film's depiction of the band's acrimony and attempts to recapture the group's spirit a significant poignancy.

Individual projects

In late 1966, John Lennon took time off to play a supporting character, Gripweed, in a film called How I Won the War, also directed by Lester. It was a satire of World War II films, and its dry, ironic British humour was not well received by American audiences. He would later produce avant-garde films with his second wife Yoko Ono, such as Rape which was produced for the Austrian television network ORF.

In 1969, Ringo Starr took second billing to Peter Sellers in the satirical comedy The Magic Christian, in a part which had been written especially for him. In 1971, Starr played the part of Frank Zappa in Zappa's epic cult film about a rock and roll band touring, entitled 200 Motels. In 1973, Ringo played the part of Mike in That'll Be The Day along with David Essex as Jim MacLaine. In 1974, Ringo starred with musician Harry Nilsson in the film Son of Dracula and in 1981, starred in the film Caveman with Shelley Long.

Starr later embarked on an irregular career in comedy films through the early 1980s, and his interest in the subject led him to be the most active of the group in the film division of Apple Corps, although it was Harrison who would achieve the most success as a film producer (The Life of Brian, Mona Lisa, Time Bandits, Shanghai Surprise, Withnail and I) and even made cameo appearances in some of these as well (including a reporter in All You Need Is Cash).

Paul McCartney appeared in a cameo role in Peter Richardson's 1987 film Eat the Rich and released his own film Give My Regards to Broad Street in 1984 in which Ringo Starr co-starred.

Unmade films

During the 1960s, there were many ideas pitched for films, but these were either rejected or else never saw the light of day; such projects included A Talent for Loving, a Western film written by Richard Condon; Shades of a Personality; film versions of The Lord of the Rings and The Three Musketeers starring the group (although Richard Lester, who directed the group's first two movies, went on to direct his own version of The Three Musketeers in 1973), and a script by playwright Joe Orton called Up Against It.[4] Robert Zemekis was planning a remake of the film Yellow Submarine with motion capture technology but it was cancelled in 2011.[5]

Critical Reception

| Film | Rotten Tomatoes | Metacritic |

|---|---|---|

| A Hard Day's Night | 98% (102 reviews)[6] | 96 (24 reviews)[7][A] |

| Help! | 91% (22 reviews)[8] | N/A |

| Magical Mystery Tour | 58% (12 reviews)[9] | N/A |

| Yellow Submarine | 96% (47 reviews)[10] | N/A |

| Let It Be | 82% (11 reviews)[11] | N/A |

| Average ratings | 85% | 96 |

- A : Ratings for the 2000 re-release.

Documentaries

The Beatles have been the subject of a number of documentary films.

- The Beatles at Shea Stadium

- The Compleat Beatles

- The Beatles: The First U.S. Visit

- The Beatles Anthology

- All Together Now

- Good Ol' Freda (December 3, 2013) Documentary about Freda Kelly, secretary of Brian Epstein and The Beatles Fan Club and her life near to the Fab Four for 11 years.

- Let It Be (1970 film)

- The Beatles: Eight Days a Week

Promotional films

- "Rain"

- "Paperback Writer"

- "Strawberry Fields Forever"

- "Penny Lane"

- "A Day in the Life"

- "Hello, Goodbye"

- "Lady Madonna"

- "Hey Jude"

- "Revolution"

- "Something"

Fictionalised Beatles

- Birth of The Beatles (1979), focusing on period from ca. 1957 at art college through Hamburg days to first number one

- Beatlemania (1981), a poorly received movie version of the Broadway show of the same name

- The Hours and Times (1991), speculation about the weekend Brian Epstein and John Lennon spent together in Barcelona in 1963

- Backbeat (1994), the Stuart Sutcliffe story

- The Linda McCartney Story (2000), A TV film covering the relationship between Paul McCartney and Linda Eastman.

- Two of Us (2000), covering a mid-1970s meeting between Paul McCartney and John Lennon

- In His Life: The John Lennon Story (2000), focusing on period from 1957 to 1964.

- Nowhere Boy (2009), a John Lennon biopic, focusing on his teens

- Lennon Naked (2010), a TV movie based on the life of Lennon from 1967 to 1971 starring Christopher Eccleston as John Lennon

Inspired by The Beatles

Several fictional films not depicting The Beatles have been entirely based on Beatles themes and songs

- Pinoy Beatles (1964), a Tagalog musical made in the Philippines. It was released 3 months after A Hard Day's Night

- The Girls on the Beach (1965), a beach party film in which college coeds mistakenly believe the Beatles are going to perform at their sorority fundraiser

- All This and World War II (1976), documentary of World War II using Beatles music

- Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1978), a musical based on the Beatles' album of the same name

- I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978), a coming of age film about Beatlemania

- All You Need Is Cash (1978), TV mockumentary featuring The Rutles, a parody of the Beatles

- Secrets (1992), a drama about five Australian teenagers who get locked in the basement of a hotel where the Beatles are staying

- I Am Sam (2001), a drama about the story of an intellectually disabled father who loves the Beatles and his efforts to retain custody of his daughter

- The Rutles 2: Can't Buy Me Lunch (2005), mockumentary featuring The Rutles

- Across the Universe (2007), a musical

- Beatles (2014) Norwegian film based on Beatles (novel) written by Lars Saabye Christensen. It's about five boys in the seventh grade in school, they live on the west side of Oslo, they are all great fans of the band "The Beatles".

Other

- Howard Kaylan's autobiographical film, My Dinner with Jimi, from 2003, tells the story of Kaylan and his band The Turtles' first tour of England, where they met many British rock stars, including The Beatles. John Lennon was portrayed by Brian Groh; Paul McCartney, by Quinton Flynn; George Harrison, by Nate Dushku and Ringo Starr, by Ben Bodé.

- In the 2007 mock-biopic film Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story, Dewey Cox and his bandmates go to India to pray with the Maharishi. There, they encounter the intentionally miscast Beatles with Paul Rudd, Jack Black, Justin Long and Jason Schwartzman as John, Paul, George and Ringo, respectively.

- The vultures in the 1967 film of The Jungle Book are considered caricatures of the Beatles. The Beatles were originally planned to voice them, but later declined due to scheduling conflicts.[12]

References

- ↑ Sarris, Andrew (2004). "A Hard Day's Night". In Elizabeth Thomson, David Gutman. The Lennon Companion. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81270-3.

- ↑ Schickel, Richard, Corliss, Richard (19 February 2007). "ALL-TIME 100 MOVIES". Time. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

- ↑ "Magical Mystery Tour". Televisionheaven.co.uk. Retrieved 2011-08-20.

- ↑ "Joe Orton and the Lost Beatles film". Beatlesagain.com. Retrieved 2011-08-20.

- ↑ Kit, Borys. Disney torpedoes Zemeckis' "Yellow Submarine" The Hollywood Reporter (14 March 2011).

- ↑ "A Hard Day's Night (1964)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 2016-09-11.

- ↑ "A Hard Day's Night - Season 1 Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 2016-09-11.

- ↑ "Help! (1965)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 2016-09-11.

- ↑ "Magical Mystery Tour (1967)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 2016-09-11.

- ↑ "Yellow Submarine (1968)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 2016-09-11.

- ↑ "Let It Be (1970)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 2016-09-11.

- ↑ Kumar, Sujay (2010-10-07). "11 On-Screen Portrayals of the Beatles". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 2011-09-26.