The Pianist (memoir)

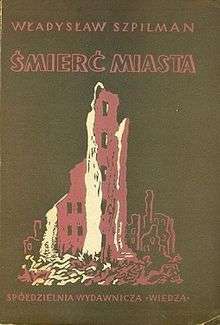

First edition | |

| Author | Wladyslaw Szpilman |

|---|---|

| Original title | Śmierć miasta |

| Translator | Anthea Bell |

| Country | Warsaw, Poland |

| Language | Polish |

| Genre | Diary, memoir, autobiography |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 224 pp |

| ISBN | 978-0-7538-1405-5 (new ed.) |

| OCLC | 59463310 |

The Pianist is a memoir of the Polish composer of Jewish origin Władysław Szpilman, elaborated by Jerzy Waldorff, who met Szpilman in 1938 in Krynica. The book tells how Szpilman survived the German deportations of Jews to extermination camps, the 1943 destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto, and the 1944 Warsaw Uprising during World War II.[1]

The book, originally entitled Death of a City (Śmierć miasta), was first published by the Polish publishing house Wiedza in 1946.[2] In the introduction to its first edition, Jerzy Waldorff stated that he wrote down "as closely as he could" the story told to him by Szpilman, and that he used also Szpilmans notes in the process. In the same year, novelists Jerzy Andrzejewski and Czesław Miłosz wrote a screenplay based on it, for the movie called The Warsaw Robinson (Robinson Warszawski).[3] In the next three years a number of drastic revisions were requested by the Communist Party, prompting Miłosz to quit and withdraw his name from the credits. The movie was released during the Conference of Poland's Filmographers in Wisła on November 19–22, 1949 and met with a new wave of political criticism. Further revisions were requested and new music commissioned, and the movie was re-released in popular movie theatres in December 1950 under a different title: Unsubjugated City (Miasto nieujarzmione).[1]

Because of Stalinist cultural policy and the ostensibly "grey areas" in which Szpilman asserted that not all Germans were bad and not all of the oppressed were good, the actual book remained sidelined for more than 50 years. The latest editions were expanded and published with foreword by Andrzej Szpilman (Szpilman’s son) under a different title, The Pianist. In the preface to the new edition Andrzej Szpilman confirmed: "My father is not a writer. He wrote the first version of this book in 1945, I suspect for himself rather than humanity in general. It enabled him to work trough his shattering wartime experiences and free his mind and emotions to continue with his life".[4] Andrzej Szpilman republished his father's memoir in 1998 first in German as Das wunderbare Überleben (The Miraculous Survival) and then in English as The Pianist.

In 2002, Roman Polanski directed a screen version, also called The Pianist, but Szpilman died before the film was completed. The movie won three Academy Awards, the British Academy of Film and Television Arts Best Film Award, and the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival.

Synopsis

Władysław Szpilman studied the piano in the early 1930s in Warsaw and Berlin. In Berlin, he was instructed by Leonid Kreutzer and, at the Berlin Academy of Arts, by Artur Schnabel. During his time at the academy he also studied composition with Franz Schreker. In 1933, he returned to Warsaw after Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party rose to power in Germany.

Upon his return to Warsaw, Szpilman worked as a pianist for Polish Radio until the German invasion of Poland in 1939. He was forced to stop work at the station when German bombs destroyed the power station that kept Polish Radio running. He played Polish Radio’s last ever pre-war live recording (a Chopin recital) the day the station went off the air.

Only days after Warsaw’s surrender, German leaflets appeared, hung on the walls of buildings. These leaflets, issued by the German commandant, promised Poles the protection and care of the German State. There was even a special section devoted to Jews, guaranteeing them that their rights, their property, and their lives would be absolutely secure. At first, these proclamations seemed trustworthy, and opinion was rife that Germany’s invasion may have even been a good thing for Poland; it would restore order to Poland’s present state of chaos. But, soon after the taking of the city, popular feeling began to change. The first clumsily organised race raids, in which Jews were taken from the streets into private cars and tormented and abused, began almost immediately after peace had returned to the city. But the occurrence that first outraged the majority of Poles was the murder of a hundred innocent Polish citizens in December 1939. After this, Polish opinion turned strongly against the occupying army, especially the organisation responsible for the majority of civilian murders, the SS.

Soon, decrees applying only to Jews began to be posted around the city. Jews had to hand real estate and valuables over to German officials and Jewish families were only permitted to own 2000 złoty each. The rest had to be deposited in a bank in a blocked account. Unsurprisingly, very few people handed their property over to the Germans willingly in compliance with this decree. Szpilman’s family (he was living with his parents, his brother Henryk, and his sisters Regina and Halina) were among those who did not. They hid their money in the window frame, an expensive gold watch under their cupboard, and the watch’s chain beneath the fingerboard of Szpilman’s father’s violin.

Creation of the Ghetto

By 1940, many of the roads leading into the area set aside for the ghetto were being blocked off with walls. No reason was given for the construction work. Also in January and February 1940, the first decrees appeared ordering Jewish men and women each to do two years of labour in concentration camps. These years would serve to cure Jews of being "parasites on the healthy organism of the Aryan peoples". But the threats of labour camps didn’t come into effect until May, when Germany took Paris. Now, having expanded the bounds of the Reich by a significant distance, the Nazis had time to spare to persecute the Jews. Deportations, German robberies, murders, and forced labour were stepped up significantly. To avoid the concentration camps, rich, intellectual Jews like Szpilman’s family and many of his acquaintances could pay to have poorer Jews deported in their place. These payments would be made to the Judenrat, the Jewish organisation that the Germans had put in charge of arranging the deportation. Most of the money went to supporting the high-cost living standards of those at the head of the council.

For the Jews of Warsaw, the worst was yet to come. In The Pianist, Szpilman describes a newspaper article that appeared in October 1940 soon after the Ghetto was officially pronounced by the German Governor-General Hans Frank:

A little while later the only Warsaw newspaper published in Polish by the Germans provided an official comment on this subject: not only were the Jews social parasites, they also spread infection. They were not, said the report, to be shut up in a ghetto; even the word “ghetto” was not to be used. The Germans were too cultured and magnanimous a race, said the newspaper, to confine even parasites like the Jews to ghettos, a medieval remnant unworthy of the new order in Europe. Instead, there was to be a separate Jewish quarter of the city where only Jews lived, where they would enjoy total freedom, and where they could continue to practise their racial customs and culture. Purely for hygienic reasons, this quarter was to be surrounded by a wall so that typhus and other Jewish diseases could not spread to other parts of the city.

And so the Warsaw Ghetto was formed.

Life in the Ghetto

Szpilman’s family was lucky to already be living in the ghetto area when the plans were announced. Other families, living outside the boundaries, had to find new homes within the ghetto’s confines. They had been given just over a month’s warning by the notices and many families were forced to pay exorbitant amounts of money for tiny slums in the bad areas of the ghetto.

On 15 November 1940, the gates of the ghetto were closed. However, this didn’t stop the smuggling trade into the “Jewish Quarter". Expensive luxury goods as well as food and drink came into the ghetto, heaped in wagons and carts. Although these convoys were not strictly legal, the two men in charge of the business, Kon and Heller (who were in the service of the Gestapo and through them could run many such ventures), paid the guards at the ghetto gate to turn a blind eye at a prearranged time and allow the carts through. There were other, less organised types of smuggling that occurred regularly in the ghetto. Every afternoon (afternoon was the best time for smuggling as by then the police guarding the wall were tired and uninterested) carts would pass by the ghetto wall, a whistle would be heard, and bags of staple food would be thrown into the ghetto. The poor inhabitants of the houses by the wall would scamper out of cover, grab the food, and return to their lodgings. Szpilman played piano at an expensive café which pandered to the ghetto’s upper class, largely smugglers and other war profiteers, and their wives or mistresses. On his way to or from work, Szpilman would sometimes pass by the wall during smuggling hours. In addition to the methods of smuggling mentioned previously, Szpilman observed many child smugglers at work. These smugglers were children who, of their own volition or on the instructions of family members or employers, sneaked out of the ghetto through gutters that ran from the Aryan side of the wall to the Jewish side. Children did the work as they were the only ones small enough to squeeze through without becoming stuck. Once they had gotten to the other side and received their bags of goods, they would return to the ghetto through the gutters. In his memoir, Szpilman describes one of these forays:

One day when I was walking along beside the wall I saw a childish smuggling operation that seemed to have reached a successful conclusion. The Jewish child still on the far side of the wall only needed to follow his goods back through the opening. His skinny little figure was already partly in view when he suddenly began screaming, and at the same time I heard the hoarse bellowing of a German on the other side of the wall. I ran to the child to help him squeeze through as quickly as possible, but in defiance of our efforts his hips stuck in the drain. I pulled at his little arms with all my might, while his screams became increasingly desperate, and I could hear the heavy blows struck by the policeman on the other side of the wall. When I finally managed to pull the child through, he died. His spine had been shattered.

As time went by, the area of the ghetto was slowly decreased until there was a small ghetto, made up mostly of intelligentsia and middle – upper class, and a large ghetto that held the rest of the Warsaw Jews. Szpilman and his family were fortunate to live in the small ghetto, which was less crowded and dangerous than the other. The large ghetto was reached from the small ghetto by crossing Chłodna Stree in the Aryan part of the city. Again, the experience of those in the bigger ghetto is best described by Szpilman:

Dozens of beggars lay in wait for this brief moment of encounter with a prosperous citizen, mobbing him by pulling at his clothes, barring his way, begging, weeping, shouting, threatening. But it was foolish for anyone to feel sympathy and give a beggar something, for then the shouting would rise to a howl. That signal would bring more and more wretched figures streaming up from all sides, and the good Samaritan would find himself besieged, hemmed in by ragged apparitions spraying him with tubercular saliva, by children covered with oozing sores who were pushed into his path, by gesticulating stumps of arms, blinded eyes, toothless, stinking open mouths, all begging for mercy at this, the last moment of their lives, as if their end could be delayed only by instant support.

Whenever he went into the large ghetto, Szpilman would visit a friend, Jehuda Zyskind, who worked as a smuggler, trader, driver, or carrier when the need arose. He was also an enthusiastic Socialist. This interest was what eventually led to his and his family’s death: shot on the spot by Military Police officers after being caught sorting out a pile of socialist documents, illegally smuggled into the ghetto. But before his death, in the winter of 1942, Zyskind supplied Szpilman with the latest news from outside the ghetto, received via radio. After hearing this news and completing whatever other business he had in the large ghetto, Szpilman would head back to his house in the small ghetto. On his way, Szpilman would meet up with his brother, Henryk, who made a living by trading books in the street. He would help Henryk to carry the books back to the family house, where they would have lunch.

Henryk, like Władysław, was cultured and well educated. Many of his friends advised him, at one time or another, to do as most young men of the intelligentsia and join the Jewish Ghetto Police, an organisation of Jews who worked under the SS, upholding their laws in the ghetto. Henryk, however, refused to work with “bandits”. Soon enough, Henryk’s decision was proved to have been a wise one. In May 1942, the Jewish Police began to carry out the task of “human-hunting” for the Germans, mistreating Jews almost as viciously as their German employers. Szpilman describes the Jewish Police:

You could have said, perhaps, that they caught the Gestapo spirit. As soon as they put on their uniforms and police caps and picked up their rubber truncheons, their natures changed. Now their ultimate ambition was to be in close touch with the Gestapo, to be useful to Gestapo officers, parade down the street with them, show off their knowledge of the German language and vie with their masters in the harshness of their dealings with the Jewish population.

During a “human-hunt” conducted by the Jewish Police, Henryk was picked up and arrested. As soon as he heard the news of his brother’s arrest, Szpilman went to the labour bureau building, determined to secure Henryk’s release. His only hope was that his popularity as a pianist would be enough to secure Henryk’s release and stop himself from being arrested as well, for none of his papers were in order. Still, Szpilman made his way to the building and, amongst a crowd of prisoners being herded into captivity, managed to find the deputy director of the labour bureau. After much effort, Szpilman managed to extract from him a promise that Henryk would be home by that night, which he was.

The rest of the men who had been arrested during the sweep were taken to Treblinka, a German extermination camp, to test the new gas chambers and crematorium furnaces.

The Umschlagplatz

On 22 July 1942, the resettlement plan was first put into action. Buildings, randomly selected from all areas of the Ghetto, were surrounded by German officers leading troops of Jewish Police. The inhabitants were called out, the building was searched, and every single person removed from the building, including babies and old men and women, was loaded into wagons and taken to the Umschlagplatz (the assembly area). From there, Jews were loaded into trains and taken away. Notices posted around the city said that all Jews fit to work were going to the East to work in German factories. They would each be allowed 20 kilograms of luggage, jewelry, and provisions for two days. Only Jewish officials from the Judenräte or other social institutions were exempt from resettlement.

In the hope of being allowed to stay in Warsaw if they were useful to the German community, Jews tried to find work at German firms that were recruiting within the ghetto. If they managed to find work, often by paying their employer to hire them, Jews would be issued with certificates of employment. They would pin notices bearing the name of the place where they were working onto their clothing.

After six days searching and deal making, Szpilman managed to procure six work certificates, enough for his entire family. At this time, Henryk, Władysław and their father were given work sorting the stolen possessions of Jewish families at the collection centre near the Umschlagplatz. They and the rest of the family were allowed to move into the barracks for Jewish workers at the centre.

But, on 16 August 1942, Szpilman’s luck ran out. On that day there was a selection carried out at the collection centre and only Henryk and Halina were passed as fit to work and allowed to stay. The rest of the family was taken to the Umschlagplatz.

Soon after they arrived, Szpilman’s family was reunited. Henryk and Halina, working in the collection centre, had heard about the plight of the rest of the family and volunteered of their own will to go to the Umschlagplatz. Szpilman was horrified and angered by his siblings’ headstrong decision, and only accepted their presence after his appeal to the guards had failed to secure their release. The family sat together in the large open space that was the Umschlagplatz. Szpilman describes their last moments together before the train arrived:

At one point a boy made his way through the crowd in our direction with a box of sweets on a string round his neck. He was selling them at ridiculous prices, although heaven knows what he thought he was going to do with the money. Scraping together the last of our small change, we bought a single cream caramel. Father divided it into six parts with his penknife. That was our last meal together.

That night, at around six o’clock, the transports were filled, in preparation for leaving the Umschlagplatz. Szpilman describes his last moments with his family:

By the time we had made our way to the train the first trucks were already full. People were standing in them pressed close to each other. SS men were still pushing with their rifle butts, although there were loud cries from inside and complaints about the lack of air. And indeed the smell of chlorine made breathing difficult, even some distance from the trucks. What went on in there if the floors had to be so heavily chlorinated? We had gone about halfway down the train when I suddenly heard someone shout, 'Here! Here, Szpilman!’ A hand grabbed me by the collar, and I was flung back and out of the police cordon.

Who dared do such a thing? I didn't want to be parted from my family. I wanted to stay with them!

Death of a City

Szpilman never saw any members of his family again. The train they were on took them to Treblinka. None of them survived the war.

Szpilman got work to keep himself safe. His first job was as part of a column of workers the Germans were using to demolish the walls of the large ghetto, for now that most of the Jews there had been deported, it was being reclaimed by the rest of the city. Whilst doing this new work, Szpilman was permitted to go out into the Gentile side of Warsaw. If they could slip away from the wall, Szpilman and the other workers visited Polish food stalls and purchased such staples as potatoes and bread. These precious purchases could either be eaten by the buyer or taken into the ghetto, where their value skyrocketed. By eating some of their food and selling or trading the rest in the ghetto, the men working on the wall could feed themselves adequately and still raise enough money to repeat the exercise the next day.

After his work on the wall Szpilman survived another selection in the ghetto and was sent to work on many different tasks, such as cleaning out the yard of the Jewish council building. Eventually, Szpilman was posted to a steady job as "storeroom manager". In this position, Szpilman organised the stores at the SS accommodation, which his group was preparing. At around this time, the Germans in charge of Szpilman’s group decided to allow each man five kilograms of potatoes and a loaf of bread every day, to make them feel more secure under the Germans; fears of deportation had been running at especially high levels since the last selection. To get this food, the men were allowed to choose a representative to go into the city with a cart everyday and buy it for all of them. To do this they chose a young man known to Szpilman as “Majorek” (Little Major). Majorek acted not only to collect food, but as a link between the Jewish resistance in the ghetto and similar organisations outside, as well. Hidden inside his bags of food every day, Majorek would bring weapons and ammunition into the ghetto to be passed on to the resistance by Szpilman and the other workers. Majorek was also a link to Szpilman’s Polish friends and acquaintances on the outside; through Majorek, Szpilman managed to arrange his escape from the ghetto.

On February 13, 1943, Szpilman slipped through the ghetto gate and met up with his friend Andrzej Bogucki on the other side. As soon as he saw Szpilman coming, Bogucki turned away and began to walk towards the hiding place they had arranged for him. Szpilman followed, careful not to reveal himself as Jewish (Szpilman had prominent Jewish features) by straying into the light of a street lamp while a German was passing.

Szpilman only stayed in his first hiding place for a few days before he moved on. While hiding in the city, Szpilman had to move many times from flat to flat. Each time he would be provided with food by friends involved in the Polish resistance who, with one or two exceptions, came irregularly but as often as they were able. These months were long and boring for Szpilman; he passed his time by learning to cook elaborate meals silently and out of virtually nothing, by reading, and by teaching himself English. During this entire period Szpilman lived in fear of capture by the Germans. If he were ever discovered and unable to escape, Szpilman planned to commit suicide so that he would be unable to compromise any of his helpers under questioning. During the months Szpilman spent in hiding, he came extremely close to suicide on several occasions, but never had to carry out his plans.

Szpilman continued to live in his various hiding places until August 1944. In August, the Warsaw Uprising, the Polish underground's large-scale effort to fight the German occupiers, began, only weeks after the first Soviet shells had fallen on the city. As a result of this Soviet attack the German authorities had begun tentatively to evacuate the civilian population of the city, but there was still a strong military presence within Warsaw, and this was what the Warsaw rebellion was aimed at.

From the window of the flat in which he was hiding, Szpilman had a good vantage point from which to watch the beginnings of the rebellion. Hiding in a predominantly German area, however, Szpilman was not in a good position to go out and join the fighting: first he would need to get past several units of German soldiers who were holding the area against the main power of the rebellion, which was based in the city centre. So Szpilman stayed in his building. However, on August 12, 1944, the German search for the culprits behind the rebellion reached Szpilman’s building. It was surrounded by Ukrainian fascists and the inhabitants were ordered to evacuate before the building was destroyed. A tank fired a couple of shots into the building and then it was set alight. Szpilman, hiding in his flat on the fourth floor, could only hope that the flats on the first floor were the only ones that were burning and that he would be able to escape the flames by staying high. Within hours, however, his room began to fill with smoke and he began to experience the beginning effects of carbon monoxide poisoning. Now, Szpilman was resigned to dying. To quicken his passing, Szpilman decided to commit suicide. To do this, he planned on swallowing first sleeping pills and then a bottle of opium to finish himself off. But he didn’t manage to see his plans through to completion. As soon as he took the sleeping pills, which acted almost instantly on his empty stomach, Szpilman fell asleep.

When he woke up, the fire was no longer burning as powerfully. All of the floors below Szpilman’s were burnt out to varying degrees, and Szpilman left the building to escape the poisonous smoke that filled all the rooms. He stopped and sat down just outside the building, leaning against a wall to conceal himself from the Germans on the road on the other side. He remained hidden behind the wall, recovering from the poison, until dark. Then he struck out across the road to an unfinished hospital building that had been evacuated already. He crossed the road on hands and knees, lying flat and pretending to be a corpse (of which there were many on the road) whenever a German unit came into sight on their way to or from fighting in the city centre. When he eventually reached the hospital, Szpilman collapsed onto the floor in the first available area and fell asleep.

The next day, Szpilman explored the hospital thoroughly. To his dismay he found that it was full of items the Germans would be intending to take away with them, meaning he would have to be careful travelling around the building in case a group should come in to loot. To avoid the patrols that occasionally swept the building, Szpilman hid in a lumber room, tucked in a remote corner of the hospital. Food and drink were scarce in the hospital, and for the first four or five days of his stay in the building, Szpilman couldn’t find anything. When, again, he went searching for food and drink, Szpilman managed to find some crusts of bread to eat and a fire bucket full of water. Even though the stinking water was covered in an iridescent film, Szpilman drank deeply, although he stopped after inadvertently swallowing a considerable amount of dead insects.

On 30 August, Szpilman moved back into his old building, which by this time had entirely burnt out. Here, in larders and bathtubs (which, due to the ravages of the fire, were now open to the air) Szpilman found bread and rainwater, which kept him alive. During his time in this building the Warsaw Uprising was defeated and the evacuation of the civilian population was completed. By October 14, Szpilman and the German army were all but the only humans still living in Warsaw, which had been completely destroyed by the Germans.

As November set in, so did winter. Living in the attic of the block of flats, with very little protection from the cold and the snow, Szpilman began to get extremely cold. As a result of the cold and the squalor, he eventually developed an insatiable craving for hot porridge. So, at great risk, Szpilman came down from the attic to find a working oven in one of the flats. He was still trying to get the stove lit when he was discovered by a German soldier. Szpilman describes the encounter:

He was as alarmed as I was by this lonely encounter in the ruins, but he tried to seem threatening. He asked, in broken Polish, what I was doing here. I said I was living outside Warsaw now and had come back to fetch some of my things. In view of my appearance, this was a ridiculous explanation. The German pointed his gun at me and told me to follow him. I said I would, but my death would be on his conscience, and if he let me stay here I would give him half a litre of spirits. He expressed himself agreeable to this form of ransom, but made it very clear that he would return, and then I would have to give him more strong liquor. As soon as I was alone I climbed quickly to the attic, pulled up the ladder and closed the trapdoor. Sure enough, he was back after quarter of an hour, but accompanied by several other soldiers and a non-commissioned officer. At the sound of their footsteps and voices I clambered up from the attic floor to the top of the intact piece of roof, which had a steep slope. I lay flat on my stomach with my feet braced against the gutter. If it had buckled or given way, I would have slipped to the roofing sheet and then fallen five floors to the street below. But the gutter held, and this new and indeed desperate idea for a hiding place meant that my life was saved once again. The Germans searched the whole building, piling up tables and chairs, and finally came up to my attic, but it did not occur to them to look on the roof. It must have seemed impossible for anyone to be lying there. They left empty-handed, cursing and calling me a number of names.

From then on, Szpilman decided to stay hidden on the roof every day, only coming down at dusk to search for food. He planned to go to this extra measure only until the troop of Germans who knew of his hiding place had left the area. However, he was soon forced to change his plans drastically.

Lying on the roof one day Szpilman suddenly heard a burst of firing near him. Turning, he saw that it was he that the bullets were aimed at. Two Germans, standing on the roof of the hospital, had discovered his latest hiding spot and had begun to shoot at him. Szpilman slithered, as fast as he could, off the roof and down through the trapdoor into the stairway. Then, as his last hiding place in the building had now been discovered, he hurried out of the building and into the expanse of burnt out buildings.

Wilm Hosenfeld

Szpilman headed quickly away from his old building and soon found another, similar building that he could live in. It was the only multi-story building in the area and, as was now his custom, Szpilman made his way up to the attic.

Some days later, Szpilman searched the building for food. This time his aim was to collect as much food as possible and take it all up to his attic so he would not have to come down so often and expose himself to danger. He found a kitchen and was raiding it intently when suddenly he was surprised by the voice of a German officer behind him.

The officer asked him what he was doing. Szpilman said nothing, but sat down in despair by the larder door. The officer asked him his occupation and Szpilman answered that he was a pianist. On hearing this, the officer led him to a piano in the next room and instructed him to play. Szpilman describes the scene:

I played Chopin's Nocturne in C sharp minor. The glassy, tinkling sound of the untuned strings rang through the empty flat and the stairway, floated through the ruins of the villa on the other side of the street and returned as a muted, melancholy echo. When I had finished, the silence seemed even gloomier and even more eerie than before. A cat mewed in a street somewhere. I heard a shot down below outside the building—a harsh, loud German noise.

The officer looked at me in silence. After a while he sighed, and muttered, "All the same, you shouldn't stay here. I’ll take you out of the city, to a village. You'll be safer there."

I shook my head. "I can’t leave this place," I said firmly.

Only now did he seem to understand my real reason for hiding among the ruins. He started nervously.

"You're Jewish?" he asked

"Yes."

He had been standing with his arms crossed over his chest; he now unfolded them and sat down in the armchair by the piano, as if this discovery called for lengthy reflection.

"Yes, well," he murmured, "in that case I see you really can’t leave."

The officer went with Szpilman to take a look at his hiding place. Inspecting the attic thoroughly, he found a loft above the attic that Szpilman hadn’t noticed as it was in a gloomy area of the roof. He helped Szpilman find a ladder amongst the apartments and helped him climb up into the loft. From then until his unit retreated from Warsaw, the German officer supplied Szpilman with food, water and encouraging news of the Soviet advance.

The officer’s unit left during the first half of December, 1944. The officer left Szpilman with food and drink and with a German Army great coat, so he would be warm while he foraged for food until the Soviets arrived. Szpilman had little to offer the officer by way of thanks, but told him that if he should ever need help, that he should ask for the pianist Szpilman of the Polish Radio.

The Soviets finally arrived on 15 January 1945. When the city was liberated, troops began to come in with civilians following after them, alone or in small groups. Szpilman, wishing to be friendly, came out of his hiding place and greeted one of these civilians, a woman carrying a bundle on her back. But, before he had finished speaking, the woman dropped her bundle, turned and fled, shouting that Szpilman was “A German!” Szpilman ran back inside his building.

Looking out the window minutes later, Szpilman saw that his building had been surrounded by troops and that they were already making their way in via the cellars. So Szpilman came slowly down the stairs, shouting “Don’t shoot! I’m Polish!” A young Polish officer came up the stairs towards him, pointing his pistol and telling him to put his hands up. Again Szpilman said that he was Polish. The officer came and inspected him closer. He eventually agreed that Szpilman was Polish and lowered the pistol.

After the war was over, Szpilman was visited by a violinist friend named Zygmunt Lednicki. Lednicki told Szpilman of a German officer he had met at a Soviet Prisoner of War camp on his way back from his wanderings after the defeat of the Warsaw Uprising. The officer, learning that he was a musician, had asked him if he knew Władysław Szpilman. Lednicki had said that he did, but before the German could tell him his name, the guards at the camp had asked Lednicki to move on and sat the German back down again with his fellows.

When Szpilman and Lendnicki returned to the place where the POW camp had been, it was no longer there. Although after this disappointment Szpilman did everything in his power to find the officer, it took him five years even to discover his name, Wilm Hosenfeld. From there Szpilman went to the government in an attempt to locate Hosenfeld and secure his release. But Hosenfeld and his unit, which was suspected of spying, had been moved to a POW camp at a secret location somewhere in Soviet Russia, and there was nothing the Polish government could do. Hosenfeld died in captivity in 1952.

After the war

After the war Szpilman resumed his musical career at Radio Poland in Warsaw. His first piece at the newly reconstructed recording room of Radio Warsaw was the same as the last piece he had played six years before. He went on to become the head of Polish Radio’s music department until 1963, when he retired the position to devote more of his time to composing and to touring as a concert pianist. In 1986, he retired from the latter and became a full-time composer. Szpilman died in Warsaw on 6 July 2000 at the age of 88.

Movie

A 2002 film version was adapted by Ronald Harwood and stars Adrien Brody, Emilia Fox, Thomas Kretschmann and Michał Żebrowski. The story was filmed by Roman Polanski in 2001. Polanski was awarded the Palme d'Or (Golden Palm) award of the Cannes film festival on May 26, 2002. The film eventually premiered in Cannes on May, 2002. The Pianist was nominated for several Academy Awards, including Best Picture. Brody won the Oscar for Best Actor and Polanski the one for Best Director. It has also received the César Award for Best Film in 2003.

Tagline: Music was his passion. Survival was his masterpiece.

Concert with reading

As part of the 2007 Manchester International Festival, the memoir was performed as a two-man presentation, with pianist Mikhail Rudy and actor Peter Guinness reading part of the book "The Pianist" by Władysław Szpilman as he recounts his experiences.[5] Directed by Neil Bartlett, the performance took place in an oak-beamed 1830s warehouse, which is part of the Museum of Science and Industry in Manchester site. Outside the building there are disused railway tracks, recalling the trains that took the Jews from the Ghetto to the concentration camps in Szpilman's memoirs.

The idea for the performance was originally conceived by the pianist, Mikhail Rudy, who gained the backing of Andrzej Szpilman (Władysław Szpilman's son). He also performed at the first concert dedicated to his Szpilman's music, where he met all of his living descendants. He was also shown the remains of the real-world settings of Szpilman's memoirs by the family, and has remained in contact with them since.[6]

References

- 1 2 "Film fabularny Miasto nieujarzmione (the Unsubjugated City)". Film fabularny 1945 (in Polish). Internetowa Baza Filmu Polskiego filmpolski.pl. 1998–2012. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- ↑ Jan Parker, Timothy Mathews (2011). Tradition, Translation, Trauma: The Classic and the Modern Classical Presences. Oxford University Press. pp. 278–. ISBN 0199554595. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

Google Books preview

- ↑ The Warsaw Robinson.

- ↑ Władysław Szpilman (2002) [1946]. Pianista. Warszawskie wspomnienia 1939-1945 [The Pianist. Varsovian memories 1939-1945] (PDF). Jerzy Waldorff, Andrzej Szpilman, Wilm Hosenfeld, Wolf Biermann. Krakow: Wydawnictwo Znak.

My father is not a writer. He wrote the first version of this book in 1945, I suspect for himself rather than humanity in general. It enabled him to work trough his shattering wartime experiences and free his mind and emotions to continue with his life.

- ↑ Billington, Michael (4 July 2007). "Theatre review: The Pianist / Museum of Science and Industry, Manchester". The Guardian.

- ↑ Rudy, Mikhail (29 June 2007). "Staging The Pianist". The Guardian.

External links

- Władysław Szpilman information and biography

- Szpilman's Warsaw: The History behind The Pianist (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

- (United States Copyright Office)