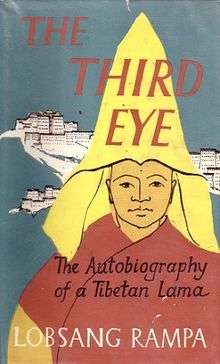

The Third Eye (book)

| |

| Author | Lobsang Rampa |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Autobiography |

| Publisher | Secker & Warburg |

Publication date | 1956 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 256 pp |

| ISBN | 978-0-345-34038-2 |

| OCLC | 2080609 |

The Third Eye is a book published by Secker & Warburg in November 1956. It was originally claimed that the book was written by a Tibetan monk named Lobsang Rampa. On investigation the author was found to be a British plumber named Cyril Henry Hoskin (1910-1981), who claimed that his body was occupied by the spirit of a Tibetan monk named Tuesday Lobsang Rampa. The book is considered to be a hoax.[1][2]

Plot

The story of The Third Eye begins in Tibet during the reign of the 13th Dalai Lama. Tuesday Lobsang Rampa, the son of a Lhasa aristocrat, takes up theological studies and is soon recognised for his prodigious abilities. As he enters adolescence, the young Rampa undertakes increasingly challenging feats until he is recognised as a crucial asset to the future of an independent Tibet. Tibet's Lamas had foretold a future in which China would attempt to reassert its authority, and Rampa is operated upon to help him preserve his country. A third eye is drilled into his forehead, allowing him to see human auras and to determine people's hidden motivations.

With his third eye, Rampa can serve as an aide in the Dalai Lama's court and spy on visitors to the court as they are being received. The visitors upon whom Rampa spies include the scholar Sir Charles Alfred Bell, deemed by Rampa as naive but benevolent. In contrast, Rampa and others are certain that Chinese visitors are nefarious and are soon to attempt to bring conquest and destruction to Tibet. Tibet must then prepare for an invasion. During the story, Rampa meets yetis, and at the end of the book he encounters a mummified body that was him in an earlier incarnation. He also takes part in an initiation ceremony in which he learns that during its early history the planet Earth was struck by another planet, causing Tibet to become the mountain kingdom that it is today. The popularity of the book led to two sequels, The Doctor from Lhasa and The Rampa Story, and Lobsang Rampa wrote over a dozen books in all.

Controversy

Although it claimed by the author to be an authentic autobiography of Rampa's education as a monk born in Tibet, the book's emphasis on the occult made scholars doubtful about its origins. The book includes a description of a surgical operation similar to trepanation in which a third eye is drilled into the forehead of Rampa, allegedly in order to enhance his psychic powers. After the book became a bestseller, Heinrich Harrer, the explorer and Tibetologist, hired the private detective Clifford Burgess to investigate the background of the author.[3] In February 1958 the results of the investigation were published in the Daily Mail. The author of the book turned out to be a man named Cyril Henry Hoskin, who came from Plympton in Devon and was the son of a plumber. Hoskin had never been to Tibet and spoke no Tibetan. When interviewed by the British press, Hoskin (who had legally changed his name to Carl Kuon So in 1948) admitted that he had written the book. He claimed in his 1960 book The Rampa Story that his body had been taken over by the Tibetan monk's spirit after falling out of an apple tree in the garden of his home. Hoskin always maintained that his books were true stories and denied any suggestions of a hoax.[4]

Responses

Although detractors regard the book as a myth of Cyril Hoskin's own creation, The Third Eye and its sequels remain the most popular publications claiming to represent life in Tibet. The dismissal of the book as a fabrication by scholars did not undermine its popularity, despite the lack of records of Rampa ever having lived and its depiction of events that are not found in the standard literature describing life in a Tibetan monastery.

Gordon Stein in Encyclopedia of Hoaxes (1993) has written:

When Tibetan Scholars examined The Third Eye, they spotted a number of obvious errors. For example, the Tibetan highlands are not at 24,000 feet altitude, but rather at 14,000 feet... Also his statement that apprentices must memorize every page of the Kan-gyur (or Bkah Hygur) to pass a test is false. Not only is this book of Buddhist Sutras not memorized, it is not even read by apprentices.[5]

Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield has cited the book as one of his early inspirations.

References

- ↑ Yapp, Nick. (1993). Hoaxers and Their Victims. Robson. pp. 140-166. ISBN 978-0860517818

- ↑ Dodin, Thierry. (1996). Imagining Tibet: Perceptions, Projections, and Fantasies. Wisdom Publications. pp. 196-200. ISBN 978-0861711918

- ↑ Tibballs, Geoff. (2006). The World's Greatest Hoaxes. Barnes & Noble. pp. 27-29. ISBN 978-0760782224 "A number of Tibetan scholars, including explorer Heinrich Harrer who had personally tutored the Dalai Lama, remained convinced that the book was pure fiction, containing, as it did, certain statements inconsistent with Buddhist beliefs. So they hired private detective Clifford Burgess to delve into the background of Tuesday Lobsang Rampa. What Burgess came up with was Cyril Hoskins, a man who had never been anywhere near Tibet, had no real knowledge of the country's language or indeed of Buddhism and had certainly never had a hole drilled in his forehead. Any expertise had been gleaned from reading books in London libraries."

- ↑ Newnham, Richard (1991). The Guinness Book of Fakes, Frauds and Forgeries. ISBN 0851129757.

- ↑ Stein, Gordon. (1993). Encyclopedia of Hoaxes. Gale Group. pp. 5-6. ISBN 0-8103-8414-0

- Lopez, Donald S., Jr. Prisoners of Shangri-LA : Tibetan Buddhism and the West,' ISBN 0-226-49311-3, discusses the influence of The Third Eye' on the Western interest in Buddhism.

- Boese, Alex. "The Third Eye".