Theatre in Qatar

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Qatar |

|---|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

|

Festivals |

| Religion |

|

Music and performing arts |

| Sport |

|

Monuments |

|

Symbols |

|

|

Theatre was introduced to Qatar in the mid-20th century. Most plays are hosted at the Qatar National Theater and the Qatar National Convention Centre.

History

The first official theatre troupe in the country was created in 1972 as the "Qatari Theatrical Troupe". It went on to produce its first play the same year.[1] The next year, a second troupe was founded as the Al Sadd Theatrical Troupe.[2] By 1986, the first company had been founded with the intent of aiding troupes and actors in producing plays.[1] Two further troupes were also created during this period: the Lights Theatrical Troupe and Folk Theatrical Troupe. In 1994, the four troupes were amalgamated into two troupes which were named the Qatari Theatrical Troupe and the Doha Theatrical Troupe.[2]

The oldest English-speaking amateur theatre club in Qatar is The Doha Players.[3] The club was formed in 1954, and created its own venue in 1978, thereby becoming the only amateur theatre club in the country have its own theatre venue at that time.[4]

Venues

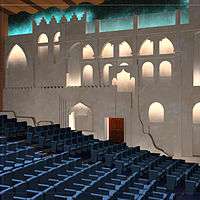

Theatrical performances are held at various venues. The Qatar National Convention Centre accommodates a 2,300-seat theatre.[5] Qatar National Theater, which is owned by the Ministry of Culture, Arts and Heritage,[6] came into operation in 1982 and has a seating capacity of 490.[7] There is an indoor theatre with seating for 430 people located in the cultural village of Katara.[8] In Souq Waqif, there is a 980-capacity indoor theatre known as Al Rayyan Theatre.[9]

Social views

Since the advent of the theatre movement in Qatar, there has been opposition towards non-traditional themes featured in plays. One factor which precipitated disapproval is the prevalence of modern plays which contradict deeply-rooted Islamic values. Another reason, which mainly accounted for opposition in theatre's inaugural years, was the ideological gap between the country's more conservative elderly population and the more liberal youth population which was caused by Qatar's rapid economic development during the mid-20th century.[10] Abdulrahman Al-Mannai wrote the first-ever play to address the conflict of values caused by the generational gap, entitled Ommul Zain.[11]

Themes related to polygamy, marriage, family issues and corruption of children are typically considered taboo. A primary reason for this is because such themes involve the questioning and scrutiny of traditionally-held values.[12] One such example is the 1985 play Ibtisam in the Dock written by Saleh Al-Mannai and Adil Saqar. The story concerns a young girl who, after entering in a secret relationship, professes to her father her disillusionments for past traditions and the suitor her family has arranged for her to marry.[13] Another play, Girls Market by Abdullah Ahmed and Asim Tawfiq, also provides social commentary on arranged marriages. It likens the act of offering women to paying suitors to trading goods on the market, hence associating arranged marriage with materialism.[14]

References

- 1 2 "Culture, Arts and Heritage". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- 1 2 Orr, Tamra (2008). Qatar. Cultures of the World. Cavendish Square Publishing. p. 98. ISBN 978-0761425663.

- ↑ "Play offers a fresh, entertaining approach to Shakespeare's works". Gulf Times. 19 February 2013. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ Barbara Bibbo' (21 March 2005). "Theatre blast stuns Qatar". Gulf News. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ↑ "Qatar National Convention Centre (QNCC), Qatar". Design Build Network. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ "Culture Ministry organizes concert". qatarisbooming.com. 11 January 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ "Qatar National Theater". Qatar Tourism Authority. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ "Drama Theatre". Katara. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ Raynald C. Rivera (18 October 2013). "Popular cartoon shows entertain audience". The Peninsula. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ↑ Muḥammad ʻAbd al-Raḥīm Qāfūd (2002), p. 58

- ↑ Muḥammad ʻAbd al-Raḥīm Qāfūd (2002), p. 61

- ↑ Muḥammad ʻAbd al-Raḥīm Qāfūd (2002), p. 67

- ↑ Muḥammad ʻAbd al-Raḥīm Qāfūd (2002), p. 68

- ↑ Muḥammad ʻAbd al-Raḥīm Qāfūd (2002), p. 72

Bibliography

- Muḥammad ʻAbd al-Raḥīm Qāfūd (2002). Studies in Qatari theatre (PDF). National Council for Culture, Arts and Heritage (Qatar).