Time derivative

A time derivative is a derivative of a function with respect to time, usually interpreted as the rate of change of the value of the function.[1] The variable denoting time is usually written as .

Notation

A variety of notations are used to denote the time derivative. In addition to the normal (Leibniz's) notation,

A very common short-hand notation used, especially in physics, is the 'over-dot'. I.E.

(This is called Newton's notation)

Higher time derivatives are also used: the second derivative with respect to time is written as

with the corresponding shorthand of .

As a generalization, the time derivative of a vector, say:

is defined as the vector whose components are the derivatives of the components of the original vector. That is,

Use in physics

Time derivatives are a key concept in physics. For example, for a changing position , its time derivative is its velocity, and its second derivative with respect to time, , is its acceleration. Even higher derivatives are sometimes also used: the third derivative of position with respect to time is known as the jerk. See motion graphs and derivatives.

A large number of fundamental equations in physics involve first or second time derivatives of quantities. Many other fundamental quantities in science are time derivatives of one another:

- force is the time derivative of momentum

- power is the time derivative of energy

- electric current is the time derivative of electric charge

and so on.

A common occurrence in physics is the time derivative of a vector, such as velocity or displacement. In dealing with such a derivative, both magnitude and orientation may depend upon time.

Example: circular motion

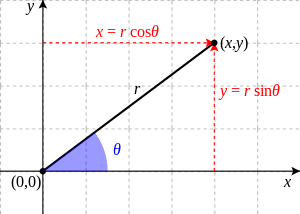

For example, consider a particle moving in a circular path. Its position is given by the displacement vector , related to the angle, θ, and radial distance, r, as defined in the figure:

For purposes of this example, set θ = t. The displacement (position) at any time t is then

This form shows the motion described by r(t) is in a circle of radius r because the magnitude of r(t) is given by

using the trigonometric identity sin2(t) + cos2(t) = 1 and where is the usual euclidean dot product.

With this form for the displacement, the velocity now is found. The time derivative of the displacement vector is the velocity vector. In general, the derivative of a vector is a vector made up of components each of which is the derivative of the corresponding component of the original vector. Thus, in this case, the velocity vector is:

Thus the velocity of the particle is nonzero even though the magnitude of the position (that is, the radius of the path) is constant. The velocity is directed perpendicular to the displacement, as can be established using the dot product:

Acceleration is then the time-derivative of velocity:

The acceleration is directed inward, toward the axis of rotation. It points opposite to the position vector and perpendicular to the velocity vector. This inward-directed acceleration is called centripetal acceleration.

Use in economics

In economics, many theoretical models of the evolution of various economic variables are constructed in continuous time and therefore employ time derivatives. See for example exogenous growth model and [2]ch. 1-3. One situation involves a stock variable and its time derivative, a flow variable. Examples include:

- The flow of net fixed investment is the time derivative of the capital stock.

- The flow of inventory investment is the time derivative of the stock of inventories.

- The growth rate of the money supply is the time derivative of the money supply divided by the money supply itself.

Sometimes the time derivative of a flow variable can appear in a model:

- The growth rate of output is the time derivative of the flow of output divided by output itself.

- The growth rate of the labor force is the time derivative of the labor force divided by the labor force itself.

And sometimes there appears a time derivative of a variable which, unlike the examples above, is not measured in units of currency:

- The time derivative of a key interest rate can appear.

- The inflation rate is the growth rate of the price level—that is, the time derivative of the price level divided by the price level itself.

See also

- Differential calculus

- Notation for differentiation

- Circular motion

- Centripetal force

- Spatial derivative

- Temporal rate

References

- ↑ Chiang, Alpha C., Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, McGraw-Hill, third edition, 1984, ch. 14, 15, 18.

- ↑ Romer, David, Advanced Macroeconomics, McGraw-Hill, 1996.