Timeline of the Spanish–American War

| Spanish–American War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Philippine Revolution and the Cuban War of Independence | |||||||||

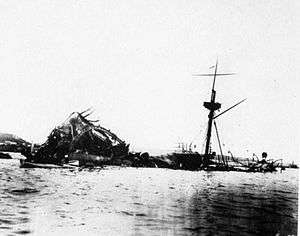

The sunken USS Maine in Havana Harbor in February 1898 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Cuban Republic:

United States:

|

Spanish Army: 10,005 regulars and militia[5](Puerto Rico), 51,331 regulars and militia[5](Philippines) | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Cuban Republic:

United States:[6]

|

| ||||||||

The timeline of events of the Spanish–American War covers major events leading up to, during, and concluding the Spanish–American War, a ten-week conflict in 1898 between Spain and the United States of America.

The conflict had its roots in the worsening socio-economic and military position of Spain after the Peninsular War, the growing confidence of the United States as a world power, a lengthy independence movement in Cuba and a nascent one in the Philippines, and strengthening economic ties between Cuba and the United States.[9] Land warfare occurred primarily in Cuba and to a much lesser extent in the Philippines. Little or no fighting occurred in Guam, Puerto Rico, or other areas.[10]

Although largely forgotten in the United States today,[11] the Spanish–American War was a formative event in American history. The destruction of the USS Maine, yellow journalism, the war slogan "Remember the Maine!", and the charge up San Juan Hill are all iconic symbols of the war.[12] The war marked the first time since the American Civil War that Americans from the North and the South fought a common enemy, and the war marked the end of strong sectional feeling and the "healing" of the wounds of that war.[13] The Spanish-American War catapulted Theodore Roosevelt to the presidency,[14] marked the beginning of the modern United States Army,[15] and led to the first establishment of American colonies overseas.[16]

The war proved seminal for Spain as well. The loss of Cuba, which was seen not as a colony but as part of Spain itself,[17] was traumatic for the Spanish government and Spanish people. This trauma led to the rise of the Generation of '98, a group of young intellectuals, authors, and artists who were deeply critical of what they perceived as conformism and ignorance on the part of the Spanish people. They successfully called for a new "Spanish national spirit" that was politically active, anti-authoritarian, and generally anti-imperialistic and anti-military.[18] The war also greatly benefited Spain economically. No longer spending large sums to maintain its colonies, significant amounts of capital were suddenly repatriated for use domestically.[19] This sudden and massive influx of capital led to the development for the first time of large, modern industries in banking, chemicals, electrical power generation, manufacturing, ship building, steel, and textiles.[20]

The war led to independence for Cuba within a few years.[21] The United States imposed a colonial government on the Philippines, quashing the young Philippine Republic. This led directly to the Philippine–American War,[22] a brutal guerilla conflict that caused the deaths of about 4,100 Americans and 12,000 to 20,000 Filipino guerilla and regular troops.[23][24] Another 200,000 to 1,500,000 Filipino civilian deaths occurred.[24][25] However, the conflict brought William Howard Taft to the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt, and led to Taft's ascension to the U.S. presidency in 1908.[26] The American presence in the Philippines still existed at the beginning of World War II. Along with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the American experience in the Philippines at the start of the war (the Philippines Campaign, the Bataan Death March, the Battle of Corregidor) became another formative episode in the American experience[27] and rehabilitated the career of General Douglas MacArthur.[28]

1892

- April 10 - After widespread discussion with Cubans living in the United States, José Martí co-founds El Partido Revolucionario Cubano (the Cuban Revolutionary Party). Its purpose is to win independence for Cuba. The organization is a reaction to nearly 15 years of economic growth, expansion of trade with the U.S., withering of trade with Spain, and extreme dissatisfaction with the peninsular caste system and socio-economic injustice.[29]

1894

- August 27 - The United States Congress enacts the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act, which imposes much higher tariffs on sugar. A suspension of Spanish tariffs on American goods expires at about the same time, leading to fears that the U.S. will retaliate against Cuba and other Spanish colonies by raising sugar and other tariffs even further. The two events devastate Cuba's economy, and Cuban sugar producers unite to try to get the Spanish tariffs lowered.[30]

1895

- February 24 - In the small town of Baire near the city of Santiago de Cuba, Martí issues the Grito de Baire, igniting the Cuban War of Independence. Within 18 months, the insurrectionists have 50,000 men under arms and uprisings have spread across the island.[31]

- June 12 - U.S. President Grover Cleveland issues a proclamation declaring the United States neutral in the Cuban war of independence.[32]

1896

- February 10 - After losing the eastern part of Cuba to the revolutionaries and witnessing the outbreak of insurrection in the western provinces, Spanish Army General Arsenio Martínez-Campos y Antón is replaced as Governor of Cuba by General Valeriano Weyler, 1st Duke of Rubí. Weyler begins a policy of recontratación ("reconcentration"), in which the people in rebel-held areas are rounded up and placed in concentration camps.[33][34] Weyler brings with him more than 200,000 Spanish Army troops, and organizes 50,000 peninsulars and Cubans into a pro-Spanish militia.[35] About 400,000 people are placed in concentration camps with little provision made for food, housing, clothing, sanitation, and medical care, and the local economy collapses in areas where the camps are created. Tens of thousands of Cubans starve to death or die from disease.[36]

- November 3 - William McKinley defeats William Jennings Bryan to become President of the United States. The Republican Party platform advocates independence and democracy for Cuba. The neutralist wing of the Democratic Party loses power in Congress as voters elect pro-Cuban Democrats.[37]

1897

- May 20 - The U.S. Congress appropriates $50,000 to provide food, clothing, and other supplies to approximately 1,200 destitute people living in Cuba who have both Cuban and American citizenship. President McKinley signs the legislation on May 24.[38]

- June 7 - United States Secretary of State John Sherman issues an official protest to the government of Spain regarding the brutality of General Weyler.[34]

- July 7 - The U.S. Congress enacts the Dingley Act, which doubles the tariff on sugar. This plunges the Cuban economy into depression.[34]

- October 6 - After Conservative Party Prime Minister Antonio Cánovas del Castillo is assassinated on August 8, Liberal Party leader Práxedes Mateo Sagasta forms a government to become Prime Minister of Spain. Sagasta recalls Weyler (replacing him with General Ramón Blanco y Erenas), offers home rule to the Cubans, and closes the concentration camps.[39] Confident of victory, the Cuban rebels reject the offer of home rule.[40]

1898

January

- January 11 - Anti-independence riots, incited by Spanish Army officers, occur in Havana, the capital of Cuba. Extensive property damage occurs as rioters demand that Spain stop giving concessions to the Cuban rebels.[41]

- January 25 - The United States Navy battleship USS Maine arrives at Havana Harbor from Key West, Florida.[42] President McKinley says the ship is on a good-will visit, but the ship is there as a show of strength to ensure American property and lives are not threatened should additional rioting occur.[43]

February

- February 9 - Enrique Dupuy de Lôme, the Spanish ambassador to the United States, is forced to resign after the De Lôme Letter is published in the New York Journal. This document, a private letter written to friend in Cuba, characterizes U.S. President McKinley as "weak" and a "would-be politician" who catered to the most jingoistic elements of the Republican Party and public. The American public is outraged at the depiction of the United States as immature, militarily weak, and lacking in diplomatic skill.[44] The Autonomous Charter of Puerto Rico, a law approved the previous November by the Cortes (the Spanish national legislature) giving local city and provincial governments of the island nearly complete autonomy, is implemented by Spanish Governor-General Manuel Macías y Casado. The first autonomous government of Puerto Rico meets the following day.[45]

- February 15 - The USS Maine explodes. About 274 of the ship's roughly 354 crew die.[46][47] A naval court of inquiry led by Captain William T. Sampson is inconclusive, but the American press and most members of Congress conclude that the Maine struck a naval mine laid by the Spanish.[48] (Subsequent investigations over the next century suggest the explosion was caused by the ignition of coal dust in the fuel bunker or a fire in the coal bunker, although some have also concluded the cause was a mine.)

- February 25 - U.S. Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt sends an order to Commodore George Dewey, commander of the U.S. Navy's Asiatic Squadron in Hong Kong, to be prepared to attack the Spanish Navy fleet in the Philippines if there is an outbreak of war. Although Secretary of the Navy John Davis Long is angered by Roosevelt's precipitate action (which occurred during his absence), he does not countermand the order.[49]

March

- March 3 - Fernando Primo de Rivera, Governor-General of the Philippines, informs the Spanish government in Madrid that the U.S. Asiatic Fleet has orders to attack Manila, capital of the Philippines, in the event of war.[50]

- March 9 - After learning that Spain was attempting to buy Brazilian warships under construction in the United Kingdom, U.S. President McKinley asks Congress for $50 million for national defense. Congress approves the request in a single day.[51] The U.S. Navy purchases the Brazilian ships instead.

- March 12 - The U.S. Navy's European Squadron is ordered to depart Lisbon, Portugal, and escort the newly purchased ships USS New Orleans (formerly the Amazonas) and the USS Albany (CL-23) (formerly the Almirante Abreu) to the United States.[52]

- March 14 - The Spanish Navy's Atlantic Squadron, commanded by Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete, leaves the Spanish port of Cadiz for the Canary Islands and then the Portuguese-held Cape Verde Islands to position itself for a dash to the West Indies in the event of war.[53] Admiral Cervera has orders to destroy Key West and blockade the East Coast of the United States, but knows that his navy is in disrepair, has no ship repair facilities in the Americas, is ill-trained, and is significantly weaker than the U.S. Navy. He advocates a defensive strategy, but is ignored.[54]

- March 19 - The battleship USS Oregon leaves Puget Sound, Washington, for Key West, accompanied by the gunboat USS Marietta.[55]

- March 26 - William T. Sampson is brevetted to Rear Admiral and ordered to take command of the U.S. Navy's North Atlantic Squadron at Key West.[56]

- March 29 - U.S. President McKinley issues an ultimatum to Spain demanding Cuban independence.[57]

April

- April 3 - An insurrection against Spanish rule breaks out on the island of Cebu in the Philippines.[58]

- April 4 - U.S. President McKinley's war message to Congress is delayed to April 6 and then April 11[59] after Spain submits a new plan (short of armistice) for Cuban autonomy and U.S. Consul-General Fitzhugh Lee in Havana asks for more time to evacuate Americans.[60] Other factors contributing to the delay include news that the Spanish Atlantic Squadron is still near the Cape Verde Islands and that U.S. Attorney General John W. Griggs needs more time to draft McKinley's message.[61]

- April 9 - Spain agrees to the March 29 ultimatum's demand that it ask for an armistice with the Cuban rebels, but the McKinley administration says the concession comes to late.[60][62] The same day, Spanish Army General Basilio Augustín becomes Governor-General of the Philippines.[63] He creates a consultative assembly to avert open rebellion against Spain, but most Filipinos reject it as illegitimate. Emilio Aguinaldo establishes military organizations in each area under Filipino rebel control.[64]

- April 11 - U.S. President McKinley submits his war message to Congress.[65]

- April 19 - The U.S. Congress enacts a joint resolution demanding independence for Cuba, and giving President McKinley the authorization to declare war if Spain does not yield. The resolution includes the Teller Amendment, which denies the U.S. the right to annex Cuba and makes it official American policy to promote Cuban democracy and independence.[66]

- April 20 - U.S. President McKinley signs the congressional joint resolution into law.[66]

- April 21 - Spain severs diplomatic relations with the United States.[66] The same day, the U.S. Navy begins a blockade of Cuba.[67] Spain mobilizes 80,000 army reserves and sends 5,000 regular army soldiers to the Canary Islands.[68]

- April 22 - U.S. President McKinley calls for 125,000 volunteers to join the National Guard of the United States, while Congress authorizes an increase in regular Army forces to 65,000.[69] The U.S. Army is small (2,143 officers and 26,040 soldiers), ill-trained, and ill-equipped. The U.S. Navy, on the other hand, is modern and well-trained, well-repaired, and well-supplied.[68]

- April 23 - Denouncing the blockade as an act of war under international law, Spain declares war on the United States.[66]

- April 25 - The U.S. Congress declares that a state of war between the U.S. and Spain has existed since April 21.[66]

- April 27 - The U.S. Asiatic Fleet leaves Mirs Bay, Hong Kong, China, and heads for Manila.[70] The same day, in the first naval action of the war, the USS New York, USS Cincinnati, USS Puritan, and other American naval ships bombard the Cuban city of Matanzas.[71] Cuban coastal defenses return fire.[72]

- April 30 - The U.S. Asiatic Fleet — consisting of the protected cruisers USS Olympia, USS Baltimore, USS Boston, and USS Raleigh; gunboats USS Concord and USS Petrel; and revenue cutter USS McCulloch — arrives at Cape Bolinau, Luzon, the Philippines, at daybreak. Believing that the Spanish fleet is in Subic Bay, the U.S. Asiatic Fleet finds nothing, and steams for Manila Bay.[73]

May

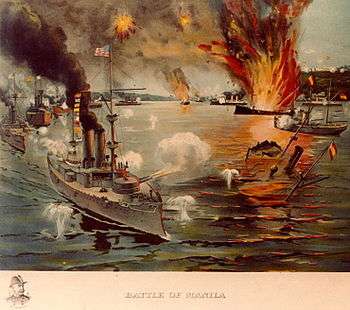

- May 1 - Battle of Manila Bay: The U.S. Asiatic Squadron enters Manila Bay at midnight. At anchor in the harbor is the out-gunned and ill-prepared Spanish fleet under the command of Admiral Patricio Montojo. At about 4:10 A.M., the American fleet engages the older Spanish vessels.[74] In the ensuing seven-hour naval battle, Spain loses all seven of its ships, 381 Spanish sailors die, and three Spanish shore batteries are destroyed. There are no American combat deaths; two U.S. Navy officers and six sailors are wounded.[75]

- May 2 - The U.S. Asiatic Fleet lacks soldiers to actually occupy territory,[76] so President McKinley authorizes U.S. Army troops to be sent to the Philippines.[77]

- May 6 - After convincing U.S. Secretary of War Russell A. Alger he can raise an all-volunteer force of 1,000 men and form a cavalry regiment, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt resigns. Alger previously offered Roosevelt a commission in the Army as a full colonel in command of a regular regiment, but Roosevelt declined.[78][79]

- May 11 - Battle of Cárdenas: Spanish shore guns repulse a U.S. Navy effort to seize the harbor at Cárdenas, Cuba. Ensign Worth Bagley is killed; he is the only U.S. Navy officer killed in combat during the entire war. The same day, the USS Nashville and USS Marblehead send 52 United States Marines ashore at Cienfuegos, Cuba, to cut the transatlantic telegraph cables with Spain. Two of the three cables are cut, and the Marines suffer heavy casualties.[80]

- May 12 - Bombardment of San Juan: The U.S. North Atlantic Squadron sails into the harbor at San Juan, Puerto Rico, where it is believed that the Spanish Atlantic Squadron has anchored. The Spanish are not there, but Rear Admiral William T. Sampson orders the city bombed anyway. Numerous civilians die.[81] Major General Wesley Merritt is appointed commander of the American force which will invade the Philippines. Merritt is eventually given more than 20,000 regular army and volunteer troops and told to occupy the entire Philippines.[82]

- May 19 - Desperately low on fuel, Admiral Cervera's Spanish Atlantic Squadron sails unopposed into the harbor at Santiago de Cuba.[83]

- May 23 - Emilio Aguinaldo declares that he has dictatorial powers over those areas of the Philippines held by Filipino rebels.[84]

- May 25 - The First Philippine Expedition, consisting of members of the U.S. Army's Eighth Army Corps, departs San Francisco, California, for Manila. The same day, U.S. President McKinley calls for an additional 75,000 volunteer soldiers.[85]

- May 29 - The U.S. Navy Flying Squadron, commanded by Commodore Winfield Scott Schley, arrives off Santiago de Cuba. Schley received orders to blockade Santiago de Cuba on May 24, but futilely awaited the Spanish Atlantic Squadron off Cienfuegos first. The Flying Squadron consists of the armored cruiser USS Brooklyn; the battleships USS Iowa, USS Massachusetts, and USS Texas; and the protected cruiser USS Marblehead.[86] The 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry — better known as the "Rough Riders" because most of the men are cowboys, frontiersmen, railroad workers, Native Americans, and similar "rough" people from the American West — depart their training camp in San Antonio, Texas. They are under the command of Colonel Leonard Wood; Theodore Roosevelt, who largely organized the unit, declines command of it. Pleading inexperience, Roosevelt accepts a commission as lieutenant colonel of volunteers and serves as Wood's subordinate.[78][87]

- May 31 - The U.S. Navy's Flying Squadron exchanges fire with the Spanish Navy's Atlantic Squadron cruiser Cristobal Colon and shore batteries at Santiago de Cuba.[85]

June

.jpg)

- June 3 - Commodore Schley's U.S. Flying Squadron, supported by Rear Admiral Sampson's U.S. North Atlantic Squadron (which arrived on June 1), attempts to block the entrance to the harbor at Santiago de Cuba by sinking the collier USS Merrimac in the main channel. Small Spanish gunboats and mines prevent the ship's proper positioning, and the harbor remains open. Assistant Naval Constructor Richmond P. Hobson and his crew of seven are captured.[88]

- June 7 - U.S. Marines from the SS St. Louis cut the submarine telegraph cable at Guantánamo Bay, severing communication between the city of Guantánamo and the rest of Cuba.[89]

- June 10 - Invasion of Guantánamo Bay: 647 U.S. Marines land at Guantánamo Bay, beginning the invasion of Cuba.[90]

- June 12 - Emilio Aguinaldo declares the independence of the Philippines.[91]

- June 13 - U.S. President McKinley signs the War Revenue Act of 1898 into law. Passed by Congress on June 10, the act authorizes a tax on amusements, liquor, tea, and tobacco, and requires tax stamps on some business transactions (such as bills of lading, manifests, and marine insurance).[92] It also authorizes $200 million in war bonds, provided that no more than $100 million in bonds is outstanding at any time.[93][94][95]

- June 16 - The Spanish Navy's 2d Squadron, under the command of Rear Admiral Manuel de la Cámara y Libermoore, departs Spain for the Philippines. The fleet consists of the battleship Pelayo, armored cruiser Emperador Carlos V, unarmored cruisers Patriota and Rapido, and two transports with 4,000 troops.[96]

- June 19 - The Rough Riders disembark from U.S. Navy vessels onto a beach near Santiago de Cuba.[87]

- June 20 - U.S. Army, U.S. Navy, and Cuban rebels meet for the Aserraderos Conference in the small town of Aserraderos (near Santiago de Cuba). They jointly plan strategy, troop movements, and battle plans.[97]

- June 21 - Capture of Guam: The American protected cruiser USS Charleston arrives at the Pacific Ocean island of Guam on June 20 and fires a few warning shots in the air, which are misinterpreted by the small Spanish garrison as a salute. (The undersea telegraph was not working, and the garrison did not know war had been declared.) The Spanish garrison formally surrenders the island without a fight on June 21.[98]

- June 22 - U.S. Major General William Rufus Shafter's Fifth Army Corps begins landing at the Cuban village of Daiquirí, 16 miles (26 km) east of Santiago de Cuba. About 6,000 men land in a chaotic operation on the first day. Among the 16,888 troops are 15 regiments of regulars and three regiments of volunteers. Spanish Army Lieutenant General Arsenio Linares y Pombo has 12,000 soldiers in the surrounding hills, but does not oppose the landings.[99] The cruiser USS Saint Paul, commanded by Captain Charles D. Sigsbee (former commander of the USS Maine), disables the Spanish Navy destroyer Terror while blockading San Juan, Puerto Rico.[100]

- June 23 - A division of the American Fifth Corps seizes the village of Siboney, Cuba, without a fight. Siboney, just 9 miles (14 km) from Santiago de Cuba, becomes the corps headquarters.[99]

- June 24 - Battle of Las Guasimas: Major General Joseph Wheeler learns that Spanish Army forces are digging in along a ridge above El Camino Real (the "Royal Road") near the village of Las Guásimas, 3 miles (4.8 km) west of Siboney. Wheeler orders Brigadier General S. B. M. Young to lead the 1st Cavalry Regiment, 10th Cavalry Regiment (a racially segregated unit of African American soldiers), and the Rough Riders to attack the position, apparently knowing that Spanish Army Brigadier General Antero Rubín has orders to withdraw. The Spanish — outnumbering the Americans 1,500 to 1,000, and armed with superior 7mm 1893 model Mauser repetition rifles firing ammunition propelled by smokeless gunpowder — hold off the U.S. 1st Cavalry. Led by Lt. Colonel Roosevelt, three companies of the Rough Riders try to outflank the Spanish and succeed to some extent. After two hours, the Spanish withdraw as scheduled. The Americans claim victory, but were much closer to defeat.[101]

- June 28 - U.S. President McKinley extends the American naval blockade to Puerto Rico. The cruiser USS Yosemite attacks the Spanish Navy transport Antonio Lopez, which is defended by the Spanish cruisers Isabel II and Alfonso XIII. Although the Antonio Lopez is run aground near the city of San Juan and destroyed, most of her cargo (including heavy artillery) is saved by the Spanish.[100][102]

- June 30 - The first 2,500 U.S. Army troops arrive in Manila Bay in the Philippines and come ashore at Cavite.[102] American troops attempt a landing and are repulsed at the Battle of Tayacoba.[103]

July

- July 1 - Battle of the Aguadores: In support of U.S. Army troops moving on Santiago de Cuba, Brigadier General Henry M. Duffield leads a brigade consisting of the 33rd Michigan Volunteer Infantry, 34th Michigan Volunteer Infantry, and 9th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry in a feint toward the Aguadores River. The railway trestle over the river is destroyed, preventing an American crossing. His 2,500 soldiers are stopped by about 275 Spanish Army soldiers, and Duffield withdraws.[104] Battle of El Caney: 520 Spanish Army soldiers under the command of Brigadier General Joaquín Vara del Rey y Rubio hold off 6,653 men of Fifth Army Corps' 2d Division, led by Brigadier General Henry Ware Lawton. Heavy ground cover delayed and exhausted the U.S. troops as they climbed the hill toward El Caney, the men had little food, the underpowered American artillery was not close enough to provide cover, and six wooden blockhouses and a small stone fort give the Spanish excellent protection. The battle begins at 6:30 A.M., and was expected to last two hours; it does not end until American troops finally overrun El Caney at 5:00 P.M. Vara del Rey is killed.[105] Battles of San Juan Hill and Kettle Hill: Two elements of Fifth Corps — the 1st Division, under the command of U.S. Brigadier General Jacob Ford Kent, and the Cavalry Division (dismounted) under the command of Executive Officer Samuel S. Sumner (General Wheeler was ill) — assault San Juan Hill and Kettle Hill (named for the large iron sugar-cooking kettles on its slopes) overlooking Santiago de Cuba. The 15,000 American soldiers are opposed by 800 men of the Spanish Army's IV Corps under the command of General Linares. The attack on Kettle Hill is led by one element of the Cavalry Division's 1st Brigade (the 3rd U.S. Cavalry) and two elements of the Cavalry Division's 2d Brigade (the Rough Riders and the all-black 10th Cavalry). The assault is initially slowed as U.S. soldiers suffer from heat exhaustion, but effective fire from American Gatling guns and "the charge up San Juan Hill" by Theodore Roosevelt's Rough Riders secure the heights. U.S. troops on Kettle Hill briefly take Spanish artillery fire from San Juan Hill until it, too, is taken relatively easily. All U.S. objectives at San Juan Heights are secure by 1:30 P.M.[106]

- July 2 - U.S. General Shafter sends a message to Admiral Sampson, requesting that the U.S. Navy force its way into Santiago de Cuba's harbor and destroy the shore batteries and artillery there. "Sampson is appalled" as he realizes the U.S. Army has suffered such grievous losses from disease that it needs the U.S. Navy to capture the city for it.[100]

- July 3 - Battle of Santiago de Cuba: On July 1, the Spanish Governor of Cuba, General Blanco, ordered Admiral Cervera to run the blockade and escape the harbor at Santiago de Cuba. Cervera does so at 9:00 A.M. on July 3, just hours after U.S. Rear Admiral Sampson leaves his fleet for an on-shore conference (leaving Commodore Schley in command of both the Flying Squadron and North Atlantic Squadron).[107][108] Cervera's fleet consists of the armored cruisers Infanta Maria Teresa (his flagship), Vizcaya, Cristóbal Colón, and Almirante Oquendo, and the destroyers Plutón and Furor. Although Cervera surprises the American fleet by sortying during daylight, the American ships respond quickly, and are three times larger than and outgun Cervera's ships (whose weapons are in disrepair).[108][109] The Spanish Navy loses all six ships (sank or scuttled); 323 Spanish sailors are wounded, 151 killed, and 1,720 captured, while just one American sailor is killed and one is wounded.[110][111]

- July 4 - Brigadier General Francis Vinton Greene of the U.S. Army's 2d Philippine Expeditionary Force seizes vacant Wake Island and claims it for the United States.[112] U.S. General Shafter tells General José Toral y Vázquez, commander of Spanish forces in Santiago de Cuba (in place of General Linares, who was wounded at San Juan Hill), that he will soon bombard the city and that all women and children should leave.[113] The Spanish Navy cruiser Reina Mercedes, her engines in such disrepair she is barely able to move, leaves the harbor at Santiago de Cuba and is scuttled in the main channel at 11:30 P.M. The U.S. Navy later refloats the ship and takes it back to the United States as a war prize.[111]

- July 5 - Just after midnight, the armed yacht USS Hawk intercepts the Spanish cruiser Alfonso XIII as it flees Havana Harbor. The Spanish vessel is forced to run aground, and the Hawk shells it to pieces at daylight.[111]

- July 7 - Worried about an American attack on the coast of Spain, the Spanish government tells Rear Admiral Cámara to bring the Spanish Navy's 2d Squadron, then at the mouth of the Suez Canal, back to Cadiz. This ends the Spanish attempt to oppose the U.S. Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines.[114] With U.S. President McKinley having pressed for it since June 11, Congress passes a joint resolution on June 6 annexing Hawaii. McKinley signs the legislation on July 7, and it becomes official the following day.[115]

- July 9 - The U.S. Army's Fifth Corps seals off Santiago de Cuba.[111]

- July 10–11 - Spanish artillery forces at Santiago de Cuba engage in a firefight with U.S. Army artillery in the hills surrounding the city, supported by U.S. Navy cannon fire offshore.[111]

- July 12 - Major General Nelson A. Miles, having arrived in Cuba the previous day, consults with General Shafter and Admiral Sampson about the situation in Cuba. Later that day, the USS Eagle forces the Spanish merchant blockade runner Santo Domingo aground on the Isla de la Juventud.[111]

- July 16 - Cuban rebels seize the town of Gibara from the Spanish Army without a fight.[111]

- July 17 - Siege of Santiago: Spanish General Toral offers the surrender of the 12,000 men at Santiago de Cuba, the 12,000 men at Guantánamo, and six other small Spanish Army garrisons throughout Cuba. Leonard Wood, promoted to Brigadier General, accepts the surrender and is named military governor of Santiago de Cuba. Land combat effectively ends in Cuba for the duration of the war.[116]

- July 18 - Third Battle of Manzanillo: The gunboats USS Wilmington and USS Helena, auxiliary cruisers USS Hist and USS Scorpion, and armed tugboats USS Osceola and USS Wompatuck enter the harbor at Manzanillo, Cuba, after brief naval skirmishes on June 30 and on July 1, and sink eight Spanish Navy gunboats and a merchant blockade runner.[117]

- July 21 - Battle of Nipe Bay: The U.S. Navy gunboats USS Annapolis and USS Topeka, the auxiliary cruiser USS Wasp, and the armed tugboat USS Leyden enter Nipe Bay on the northeastern coast of Cuba and find its shore battery unmanned. Inside the bay, they sink the Spanish Navy light cruiser Jorge Juan, securing the bay as a rendezvous point for U.S. military forces heading to Puerto Rico.[118] The same day, General Miles leaves Guantánamo Bay with a force of 3,400 U.S. Army soldiers, bound for Puerto Rico.[119]

- July 22 - The government of Spain asks the French ambassador to the United States, Jules Cambon, to request peace terms from the United States. The request is delayed by four days, as the Spanish give the code key for Cambon's encrypted message to the Austro-Hungarian ambassador, who is vacationing.[120]

- July 25 - Originally intending to land at Fajardo, Puerto Rico, on July 24, the U.S. Army invasion force led by General Miles changes course overnight after learning that the American press has revealed the Fajardo destination. Instead, the auxiliary cruiser USS Gloucester secures the port at Guánica, Puerto Rico, and U.S. troops come ashore there on July 25. American soldiers secure the main road to Ponce on July 26 in the "Battle of Yauco" after a brief and bloodless skirmish.[118] U.S. General Merritt reaches Manila in the Philippines. American troops there now number 10,000, and Merritt begins military operations from Cavite to capture the city.[121]

- July 26 - Having finally decrypted the Spanish government's message to him, French Ambassador Cambon passes on Spain's request for peace terms to U.S. President McKinley.[120]

- July 27 - The U.S. Navy gunboat USS Annapolis and the auxiliary cruisers USS Wasp and USS Dixie enter the undefended harbor at Ponce and threaten to bombard the town. With no Spanish official present, foreign diplomats must mediate between the U.S. Navy and the city. These diplomats telegraph the U.S. Navy's terms of surrender to the Spanish Governor-General of Puerto Rico, Manuel Macías. He reluctantly agrees to them.[122]

- July 28 - The Puerto Rican city of Ponce surrenders, and is invested with 12,000 U.S. Army troops.[122]

- July 29 - U.S. Army troops in the Philippines begin establishing an offensive line stretching from the beach at Manila Bay inland to the Calle Real (the inland road connecting Cavite with Manila).[123]

- July 31 - U.S. President McKinley gives the American terms for peace to French Ambassador Cambon: Immediate independence for Cuba, and cession of Puerto Rico to the United States in compensation for its war costs.[120]

August

.jpg)

- August 1 - Under threat of bombardment by the U.S. Navy auxiliary cruisers USS Gloucester and USS Wasp, the port of Arroyo, Puerto Rico, surrenders without a fight. A brief skirmish with Spanish Army cavalry occurs on August 3, after which 5,300 U.S. Army troops come ashore and occupy the town.[124]

- August 4 - Spain agrees to the American peace terms. In a two-and-a-half hour meeting, U.S. President McKinley and French Ambassador Cambon draft a treaty.[120] The Spanish Governor-General of the Philippines, Basilio Augustín, is replaced with Fermín Jáudenes after the Spanish government learns that Augustín attempted to surrender to U.S. Admiral George Dewey.[125] The "Round-Robin Letter" appears in U.S. newspapers. Fifth Corps departed the U.S. without proper equipment, food, or medical supplies, and is suffering from extremely poor living and sanitary conditions. The letter, written by now-Colonel Theodore Roosevelt and signed by all commanders of the corps, demands the withdrawal of the corps to the U.S. before disease decimates it. Delivered to General Shafter before its publication, U.S. Secretary of War Alger has already agreed to withdraw Fifth Corps (and does so on August 3). The American public is outraged by the scandalous living conditions under which the troops suffer.[126]

- August 5 - 5,000 U.S. Army troops under the command of Major General John R. Brooke have orders to march west along the southern coast of Puerto Rico from Arroyo to the nearby town of Guayama, then to Coamo. They are then to turn northeast and head for the inland city of Cayey. The U.S. soldiers meet stiff resistance in Guayama, but the August 5 firefight is brief and they invest the town.[127]

- August 9 - Units of Major General James H. Wilson's U.S. Army column, moving east-northeast from Ponce to Coamo and then north to the heavily concentrated Spanish Army position at Aibonito, encounter heavy resistance in Coamo. Wilson's men are forced to envelope the Spanish from the rear, killing 40 and capturing 170. Wilson suffers no dead, and just six wounded.[127]

- August 10 - 2,900 U.S. Army soldiers under the command of Brigadier General Theodore Schwan, marching from Ponce on the south-central coast of Puerto Rico northwest to Mayagüez on the western coast and then northeast to Arecibo on the north coast, encounter stiff resistance by Spanish Army forces at the village of Hormigueros, Puerto Rico. One American dies and 16 are wounded before the Spanish flee.[127]

- August 12 - U.S. Army General Wilson's command again runs into Spanish Army resistance, this time in the Asomante Hills near Aibonito. The Spanish are routed after a brief skirmish.[127] Spain and the United States sign an armistice, the "Protocol of Peace".[128]

- August 12–13 - Fourth Battle of Manzanillo: A U.S. Navy squadron consisting of the protected cruiser USS Newark, the auxiliary cruisers USS Hist and USS Suwanee, the gunboat USS Alvarado, and the armed tugboat USS Osceola bombard the Cuban port of Manzanillo and capture it.[121]

- August 13 - Battle of Manila: Manila surrenders. Governor General Jáudenes, fearing Spanish troops will be massacred by the Filipinos, agrees to surrender the city after token resistance if U.S. General Wesley Merritt excludes Filipino troops from the battle. Merritt agrees. After a brief naval bombardment, the 1st Brigade under Brigadier General Arthur MacArthur, Jr. attacks from the south while General Greene's 2d Brigade attacks from the north. There is brief Spanish resistance to MacArthur's advance after large groups of Filipinos ignore American orders to stay behind and rush the Spanish lines. Governor General Jáudenes surrenders at 11:20 A.M. after a battle lasting two hours.[129] In Puerto Rico, U.S. Army Brigadier General Schwan's command encounters Spanish Army resistance near the town of Las Marías. Word of the armistice has not yet reached Puerto Rico, and a brief skirmish ensues. It is the last battle of the war in Puerto Rico.[130]

- August 14 - The last battle of the Spanish-American War occurs off Caibarién, Cuba, when the armed supply ship USS Mangrove fires on two Spanish Navy gunboats. The Spanish surrender, and explain that an armistice has been signed.[121]

September

- September 13 - The Spanish national legislature, the Cortes, approves the Protocol of Peace by a vote of 161 to 48. But many deputies abstain, indicating a deep feeling within the Cortes that the war should continue to be prosecuted.[131]

- September 15 - The Malolos Congress, the assembly of the revolutionary government of the Philippines, convenes in Malolos, Philippines. It ratifies Aguinaldo's declaration of independence, and begins drafting a constitution for an independent Republic of the Philippines.[132]

- September 26 - The War Department Investigating Commission (also known as the "Dodge Commission" after its chairman, Major General [ret.] Grenville M. Dodge) begins investigating the conduct of the U.S. Department of War during the Spanish–American conflict. Vivid testimony by Major General Nelson A. Miles on December 21 about chemically adulterated beef bought by the department to feed soldiers in the field (the "United States Army beef scandal") leads to public outrage. The final report, issued on February 9, 1899, exonerates the War Department but subtly implies that Secretary of War Alger was an inefficient if not incompetent manager.[133] Alger denies the implication, but on July 19, 1899, he resigns (effective August 1).[134]

October

- October 1 - The Paris Peace Conference begins in Paris, France. U.S. President McKinley instructs the American chief delegate, William R. Day, to seek U.S. possession of Guam, Puerto Rico, and the island of Luzon (not the entire Philippines).[135]

- October 24 - U.S. President McKinley has a dream in which he claims God told him that the United States should seize the entire Philippines: "nothing left for us to do but to take them all, to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and Christianize them."[136]

- October 26 - U.S. President McKinley instructs the American delegation at the Paris Peace Conference to seek possession of the entire Philippines:[135] "The cession must be of the whole archipelago or none. ...latter is wholly inadmissible, and the former must therefore be required".[137]

November

- November 29 - The Malolos Congress ratifies the Malolos Constitution, a major step toward establishing the Philippines as an independent state.[138]

December

- December 10 - The Treaty of Paris is signed in Paris. Spain cedes Guam and Puerto Rico to the United States. Spain turns administration of Cuba over to the United States. The United States agrees to pay Spain $20 million in return for American possession of the Philippines.[135]

- December 21 - U.S. President McKinley issues the Proclamation of Benevolent Assimilation in which he declares the U.S. should annex the Philippines "with all possible dispatch" (e.g., by use of military force if necessary).[139]

1899

- January 21 - The Malolos Congress adjourns.[132]

- January 23 - The Philippine Republic, created by the Malolos Congress, comes into existence. Its capital is at Malolos and Emilio Aguinaldo is the first president.[139]

- February 4 - The Philippine–American War breaks out when U.S. soldiers fire on four Filipino soldiers who enter the "American Zone" in Manila. This ignites the Battle of Manila, and is the first military engagement of the second Philippine war for independence.[139]

- February 6 - The United States Senate ratifies the Treaty of Paris by a close vote of 57 to 27. (A two-thirds majority, or 56 votes, was needed to ratify.)[135] An amendment requiring the United States to give the Philippines its independence fails after Vice President Garret Hobart casts the deciding vote against it. The Senate might have declined to ratify the treaty, but the outbreak of hostilities in Manila turns the tide of feeling in the treaty's favor.[139]

- March 19 - Exercising her right to "fulfil the crown's constitutional obligations and serve the national interest" by peacefully resolving political tension, Maria Cristina, Queen Regent of Spain, signs the Treaty of Paris personally. The Cortes was deeply divided over the terms of the treaty, and deadlocked over its ratification. With ratification in jeopardy, the Queen Regent dissolved the Cortes and exercised her imperial privilege — ratifying the treaty herself.[140]

See also

- Battles of the Spanish–American War

- Commonwealth of the Philippines

- Ostend Manifesto

- Panama Canal Zone

- Spain–United States relations

- 1897-99 Imperial German plans to attack the United States and then capture Puerto Rico and Cuba

References

- 1 2 Unrecognized as participants by the primary belligerents.

- ↑ The United States was informally allied with Katipunan forces under Emilio Aguinaldo from the time of Aguinaldo's return to Manila on May 19, 1898, until those forces were absorbed into the dictatorial government proclaimed by Aguinaldo on May 24, 1898. These forces became part of the Revolutionary Government of the Philippines on June 12, 1898. The revolutionary government was informally allied with the United States until the end of the Spanish-American War.

- ↑ Dyal, p. 19.

- ↑ Dyal, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dyal, p. 20.

- 1 2 Dyal, p. 67.

- ↑ Trask, p. 371.

- 1 2 Salvadó, p. 19.

- ↑ Esdaile, p. 507-508; Hamilton, President McKinley, War and Empire: President Mckinley and the Coming of War, 1898, p. 105; "Spanish-American War and Filipino Insurrection", in The Concise Princeton Encyclopedia of American Political History, p. 523.

- ↑ Bining and Cochran, p. 503.

- ↑ Williams, p. 53.

- ↑ Jasper, Delgado, and Adams, p. 185; Cookman, p. 68; Kaplan, p. 125; Lordan, p. 14.

- ↑ Fuller, p. 7.

- ↑ Hendrickson, p. 131.

- ↑ Barnes, p. 336.

- ↑ Soltero, p. 22.

- ↑ Offner, p. 11.

- ↑ Dyal, p. 108.

- ↑ Rosa, Castro, and Blanco, p. 230.

- ↑ Herr, p. 119-120; Balfour p. 54-56.

- ↑ Pérez, p. 32-36.

- ↑ Abinales and Amoroso, p. 113.

- ↑ Hack and Rettig 2006, p. 172; "Historian Paul Kramer Revisits the Philippine–American War." The JHU Gazette. 35:29 (April 10, 2006), accessed 2013-07-18.

- 1 2 Guillermo, Emil. "A First Taste of Empire." Milwaukee Journal Sentinel February 8, 2004. Accessed 2013-07-18.

- ↑ Barnes, p. 214; Burdeos, p. 14.

- ↑ Cash, p. 202.

- ↑ Gonzalez, p. 74; Preston, p. 159.

- ↑ Zaloga, p. 10; Watson, p. 109; Jeffers, p. 100; Buhite, p. 42.

- ↑ Dominguez and Prevost, p. 25-26.

- ↑ Pérez, p. 30-32.

- ↑ Pérez, p. 7.

- ↑ LeFaber, p. 288.

- ↑ Hendrickson, p. 7.

- 1 2 3 Rockoff, p. 48.

- ↑ Offner, p. 12.

- ↑ Offner, p. 13.

- ↑ Peceny, p. 61.

- ↑ Curti, p. 199; "Cuba Relief Bill Passed." New York Times May 21, 1897; "Cuban Relief Plans." New York Times May 25, 1897.

- ↑ Rickover, p. 22.

- ↑ Zimmerman, p. 249.

- ↑ Nasaw, p. 130.

- ↑ Cummins, p. 190.

- ↑ "Spanish-American War", in Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy, p. 451.

- ↑ Offner, p. 116-119.

- ↑ Hall, "Manuel Macías y Casado", p. 358.

- ↑ Axelrod, p. 67-68.

- ↑ Accurate information for both the number of crew and dead are difficult vary widely.

- ↑ Marley, p. 598.

- ↑ Borneman, p. 1874.

- ↑ Trask, p. 68.

- ↑ "McKinley, William, and the Spanish-American War" in The War of 1898, and U.S. Interventions, 1898-1934: An Encyclopedia, p. 285.

- ↑ Maclay, p. 67. Accessed 2013-06-24.

- ↑ Hall, "Cape Tunas", p. 99.

- ↑ Dyal, p. 68-69.

- ↑ Marley, p. 908.

- ↑ Tucker, "William Thomas Sampson (1840-1902)", p. 1152.

- ↑ Tucker, "Expansion at Home and Abroad: Timeline", p. 1150, 1153.

- ↑ McCoy and De Jesus, p. 281.

- ↑ Hallett, p. 48.

- 1 2 LeFaber, p. 396.

- ↑ Offner, p. 159.

- ↑ Sweetman, p. 93.

- ↑ Alip, p. 131.

- ↑ Churchill, p. 197.

- ↑ MacCartney, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Trask, p. 57.

- ↑ "Blockades in the West Indies During the Spanish-Cuban/American War", in The War of 1898, and U.S. Interventions, 1898-1934: An Encyclopedia, p. 61.

- 1 2 Tucker, "Expansion at Home and Abroad: Timeline", p. 1154.

- ↑ McCallum, p. 306

- ↑ Lenz, p. 75.

- ↑ Pierpaoli, p. 384.

- ↑ "Chronology", in The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars, p. xxvii.

- ↑ Tucker, "Expansion at Home and Abroad: Timeline", p. 1157, 1159.

- ↑ Symonds, p. 143-149.

- ↑ Simmons, p. 69.

- ↑ Hamilton, President McKinley, War and Empire: President McKinley and America's "New Empire", p. 66.

- ↑ Tucker, "Expansion at Home and Abroad: Timeline", p. 1161.

- 1 2 Lansford, p. 46.

- ↑ Hendrickson, p. 104.

- ↑ Villafaña, p. 169.

- ↑ Drake, p. 364.

- ↑ Trask, p. 383-384.

- ↑ Trask, p. 116.

- ↑ Gentry, p. 24.

- 1 2 Barnes, p. xiv.

- ↑ Tucker, "Expansion at Home and Abroad: Timeline", p. 1163.

- 1 2 Hutton, p. 286-287.

- ↑ Trask, p. 132, 135-136.

- ↑ Hansen, p. 97.

- ↑ Trask, p. 140; Hansen, p. 98-100; Caporale, 13.

- ↑ Halili, p. 162.

- ↑ Garbade, p. 29; Jewell, p. 1895; Swaine, p. 653; Pratt, p. 117.

- ↑ Garbade, p. 42.

- ↑ The act also permitted the government to float up to $100 million in war bonds with a maturity of less than a year. This proves "a turning point" in the federal government's ability to create flexible financial instruments critical to maintaining the credit of the United States. See: Livingston, p.121.

- ↑ The estate tax was not the first estate tax enacted in the history of the United States, but its graduated nature made it the precursor to the modern federal estate tax. The 1898 estate tax was upheld by the Supreme Court of the United States in Knowlton v. Moore, 178 U.S. 41 (1900). See: Johnson and Eller, p. 69.

- ↑ Tucker, "Cámara y Libermoore, Manuel de la", p. 85.

- ↑ Trask, p. 209.

- ↑ Barnes, p. xv; Schoonover, p. 89.

- 1 2 Tucker, A Global Chronology of Conflict, p. 1506.

- 1 2 3 Sweetman, p. 98.

- ↑ Tucker, "Expansion at Home and Abroad: Timeline", p. 1169, 1171.

- 1 2 Tucker, "Expansion at Home and Abroad: Timeline", p. 1171.

- ↑ Richard H. Titherington, A History of the Spanish-American War of 1898, New York: D. Appleton and Company 1900, p. 149.

- ↑ Trask, p. 235.

- ↑ Mahon, p. 175-176; Trask, p. 235-236.

- ↑ Keenan and Tucker, p. 574; Trask, p. 237-246.

- ↑ Tucker, "Santiago de Cuba, Naval Battle of (July 3, 1898)", p. 404.

- 1 2 Marley, p. 602.

- ↑ Tucker, "Santiago de Cuba, Naval Battle of (July 3, 1898)", p. 405.

- ↑ Tucker, "Santiago de Cuba, Naval Battle of (July 3, 1898)", p. 406.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Marley, p. 603.

- ↑ Austin and Clubb, p. 76.

- ↑ Ryan, p. 280.

- ↑ Trask, p. 275-278.

- ↑ Dunlap, p. 754.

- ↑ Marley, p. 603-604.

- ↑ Sweetman, p. 99.

- 1 2 Marley, p. 604.

- ↑ Sweetman, p. 99-100.

- 1 2 3 4 Fernandez, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Sweetman, p. 100.

- 1 2 Baralt, p. 113.

- ↑ Trask, p. 412.

- ↑ Tucker, "Arroyo, Puerto Rico" p. 24.

- ↑ Lindaman and Ward, p. 115.

- ↑ Wintermute, p. 558.

- 1 2 3 4 Tucker, "Expansion at Home and Abroad: Timeline", p. 1176.

- ↑ Tucker, "Expansion at Home and Abroad: Timeline", p. 1177.

- ↑ "MacArthur, Arthur", in The War of 1898, and U.S. Interventions, 1898-1934: An Encyclopedia, p. 275.

- ↑ Tucker, "Expansion at Home and Abroad: Timeline", p. 1176-1177.

- ↑ Trask, p. 611.

- 1 2 Pollard, p. 364.

- ↑ Smith, "War Department Investigating Commission", p. 582-584.

- ↑ Schulp, p. 239.

- 1 2 3 4 Rowe, p. 624.

- ↑ Jones, p. 284.

- ↑ Ellipsis in original. Hamilton, President McKinley, War and Empire: President McKinley and America's "New Empire", p. 78.

- ↑ Pollard, p. 365.

- 1 2 3 4 Nickeson, p. 491.

- ↑ Smith, The Spanish-American War: Conflict in the Caribbean and the Pacific, 1895-1902, p. 207.

Bibliography

- Alip, Eufronio Melo (1949). Political and Cultural History of the Philippines: Since the British Occupation. Manila: Alip & Brion Publications.

- Austin, Erik W.; Clubb, Jerome M. (1986). Political Facts of the United States Since 1789. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231060943.

- Axelrod, Alex (2008). Profiles in Folly: History's Worst Decisions and Why They Went Wrong. New York: Sterling Publishing Company. ISBN 9781402747687.

- Balfour, Sebastian (1997). The End of the Spanish Empire, 1898-1923. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198205074.

- Baralt, Guillermo A. (1999). Buena Vista: Life and Work on a Puerto Rican Hacienda, 1833-1904. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807824740.

- Barnes, Mark (2010). The Spanish-American War and Philippine Insurrection, 1898–1902: An Annotated Bibliography. Florence, Ky.: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415999571.

- Bining, Arthur Cecil; Cochran, Thomas C. (1964). The Rise of American Economic Life. New York: Scribner.

- Beede, Benjamin R., ed. (1994). "Blockades in the West Indies During the Spanish-Cuban/American War". The War of 1898, and U.S. Interventions, 1898-1934: An Encyclopedia. Florence, Ky.: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780824056247.

- Borneman, Walter B. (2012). The Admirals: Nimitz, Halsey, Leahy, and King—The Five-Star Admirals Who Won the War at Sea. New York: Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 9780316097840.

- Buhite, Russell D. (2008). Douglas MacArthur: Statecraft and Stagecraft in America's East Asian Policy. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9780742544253.

- Burdeos, Ray L. (2008). Filipinos in the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard During the Vietnam War. Bloomington, Ind.: AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781434361424.

- Cash, Dane J. (2007). "William Howard Taft". In Hodge, Carl Cavanagh; Cathal J., Nolan. U.S. Presidents and Foreign Policy: From 1789 to the Present. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851097906.

- Caporale, Louis G. (2003). U.S. Marine Corps Tactical Force Development: Provisional Landing Parties to Corps Level From the American Revolution Through Vietnam. Bennington, Vt.: Merriam Press. ISBN 9781576382042.

- Tucker, Spencer, ed. (2009). "Chronology". The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099511.

- Churchill, Barnardita Reyes (1994). "Garcia, Pantaleon P.". In Beede, Benjamin R. The War of 1898, and U.S. Interventions, 1898-1934: An Encyclopedia. Florence, Ky.: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780824056247.

- Cookman, Claude Hubert (2009). American Photojournalism: Motivations and Meanings. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 9780810123588.

- Cummins, Joseph (2009). The War Chronicles, From Flintlocks to Machine Guns: A Global Reference of All the Major Modern Conflicts. Beverly, Mass.: Fair Winds Press. ISBN 9781592333059.

- Curti, Merle (1988). American Philanthropy Abroad. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Books. ISBN 088738711X.

- Dominguez, Esteban Morales; Prevost, Gary (2008). United States-Cuban Relations: A Critical History. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books. ISBN 9781461634638.

- Drake, Frederick C. (1994). "Naval Operations in the Puerto Rico Campaign (1898)". In Beede, Benjamin R. The War of 1898, and U.S. Interventions, 1898-1934: An Encyclopedia. Florence, Ky.: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780824056247.

- Dunlap, Annette B. (2012). "William McKinley". In Manweller, Matthew. Chronology of the U.S. Presidency. Volume 3: William McKinley Through John F. Kennedy. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598846454.

- Dyal, Donald H., ed. (1996). Historical Dictionary of the Spanish American War. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9781429472845.

- Esdaile, Charles (2003). The Peninsular War: A New History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403962317.

- Fernandez, Ronald (1996). The Disenchanted Island: Puerto Rico and the United States in the Twentieth Century. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. ISBN 9780275952266.

- Fuller, A. James (2007). "Introduction: Perspectives on American Power and Empire". In Sondhaus, Lawrence; Fuller, A. James. America, War and Power: Defining the State, 1775-2005. Florence, Ky.: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415772143.

- Garbade, Kenneth D. (2012). Birth of a Market: The U.S. Treasury Securities Market From the Great War to the Great Depression. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262016377.

- Gentry, John A. (2012). How Wars Are Won and Lost: Vulnerability and Military Power. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Praeger Security International. ISBN 9780313395826.

- Gonzalez, Vernadette Vicuña (2010). "Touring Military Masculinities: U.S.-Philippines Circuits of Sacrifice and Gratitude in Corregidor and Bataan". In Shigematsu, Setsu; Camacho, Keith L. Militarized Currents: Toward a Decolonized Future in Asia and the Pacific. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816665051.

- Hack, Karl; Rettig, Tobias (2006). Colonial Armies in Southeast Asia. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780203414668.

- Halili, Maria Christine N. (2004). Philippine History. Manila: Rex Book Store. ISBN 9789712339349.

- Hall, Michael R. (2009). "Cape Tunas". In Tucker, Spencer. The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099511.

- Hall, Michael R. (2009). "Manuel Macías y Casado". In Tucker, Spencer. The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099511.

- Hallett, Brien (2012). Declaring War: Congress, the President, and What the Constitution Does Not Say. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107026926.

- Hamilton, Richard F. (2006). President McKinley, War and Empire. Vol. 1, President McKinley and the Coming of War, 1898. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9780765803290.

- Hamilton, Richard F. (2008). President McKinley, War and Empire. Volume 2: President McKinley and America's "New Empire". New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412809627.

- Hansen, Jonathan M. (2011). Guantánamo: An American History. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 9780809053414.

- Hendrickson, Kenneth Elton (2003). The Spanish-American War. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313316623.

- Herr, Richard (1971). An Historical Essay on Modern Spain. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520025349.

- Hutton, Paul Andrew (2011). "TR Takes Charge". In Hutton, Paul Andrew. Western Heritage: A Selection of Wrangler Award-Winning Articles. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806189710.

- Jasper, Joy Waldron; Delgado, James P.; Adams, Jim (2001). The USS Arizona: The Ship, the Men, the Pearl Harbor Attack, and the Symbol That Aroused America. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312993511.

- Jeffers, H. Paul (2003). The USS Arizona: The Ship, the Men, the Pearl Harbor Attack, and the Symbol That Aroused America. New York: Citadel Press. ISBN 9780806524764.

- Jewell, Elizabeth (2005). U.S. Presidents Factbook. New York: Random House Reference. ISBN 9780375722882.

- Johnson, Barry W.; Eller, Martha Britton (1998). "Federal Taxation of Inheritance and Wealth Transfers". In Miller, Robert K.; McNamee, Stephen J. Inheritance and Wealth in America. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 9781489919335.

- Jones, Howard (2009). Crucible of Power: A History of American Foreign Relations to 1913. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9780742564534.

- Kaplan, Amy (2002). The Anarchy of Empire in the Making of U.S. Culture. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674009134.

- Keenan, Jerry; Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). "San Juan Heights, Battle Of". In Tucker, Spencer. The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099511.

- Lansford, Tom (2005). Theodore Roosevelt in Perspective. New York: Novinka Books. ISBN 9781594546563.

- LeFaber, Walter (1998). The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860-1898. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801485954.

- Lenz, Lawrence (2008). Power and Policy: America's First Steps to Superpower, 1889-1922. New York: Algora Publishers. ISBN 9780875866635.

- Lindaman, Dana; Ward, Kyle Roy (2006). History Lessons: How Textbooks From Around the World Portray U.S. History. New York: New Press. ISBN 9781595580825.

- Livingston, James (1989). Origins of the Federal Reserve System: Money, Class, and Corporate Capitalism, 1890-1913. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801496813.

- Lordan, Edward J. (2010). The Case for Combat: How Presidents Persuade Americans to Go to War. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Praeger. ISBN 9780313380785.

- Beede, Benjamin R., ed. (1994). "MacArthur, Arthur". The War of 1898, and U.S. Interventions, 1898-1934: An Encyclopedia. Florence, Ky.: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780824056247.

- MacCartney, Paul T. (2006). Power and Progress: American National Identity, the War of 1898, and the Rise of American Imperialism. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 9780807131145.

- Maclay, Edgar Stanton (1902). A History of the United States Navy From 1775 to 1902. New York: D. Appleton and Co.

- Mahon, John K. (1994). "El Caney, Cuba, Battle of". In Beede, Benjamin R. The War of 1898, and U.S. Interventions, 1898-1934: An Encyclopedia. Florence, Ky.: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780824056247.

- Marley, David (2008). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the Western Hemisphere, 1492 to the Present. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598841008.

- McCallum, Jack (2008). Military Medicine: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851096930.

- McCoy, Alfred; De Jesus, Ed C. (1982). Philippine Social History: Global Trade and Local Transformations. Quezon City, Manila: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 9789710200061.

- Beede, Benjamin R., ed. (1994). "McKinley, William and the Spanish-American War". The War of 1898, and U.S. Interventions, 1898-1934: An Encyclopedia. Florence, Ky.: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780824056247.

- Nasaw, David (2000). The Chief: The Life of William Randolph Hearst. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 9780395827598.

- Nickeson, Dawn Ottevaere (2009). "Philippine Islands, U.S. Acquisition of". In Tucker, Spencer. The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099511.

- Offner, John L. (1992). An Unwanted War: The Diplomacy of the United States and Spain Over Cuba, 1895-1898. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781469620596.

- Peceny, Mark (1999). Democracy at the Point of Bayonets. State College, Pa.: Penn State Press. ISBN 9780271018829.

- Pérez, Louis A. (1998). Cuba Between Empires: 1878-1902. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822956877.

- Pierpaoli, Paul G., Jr. (2009). "Matanzas, Cuba". In Tucker, Spencer. The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099511.

- Pollard, Vincent Kelly (2009). "Malolos Constitution". In Tucker, Spencer. The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099511.

- Pratt, Walter F. (1999). The Supreme Court Under Edward Douglass White, 1910-1921. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 9781570033094.

- Preston, Peter Wallace (2010). National Pasts in Europe and East Asia. New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415561136.

- Rickover, Hyman G. (1995). How the Battleship Maine Was Destroyed. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781557507174.

- Rockoff, Hugh (2012). America's Economic Way of War: War and the U.S. Economy From the Spanish-American War to the First Gulf War. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521859400.

- Rosa, Albert; Castro, Jorge; Blanco, Florentino (2006). "Otherness in Historically Situated Self-Experiences: A Case-Study on How Historical Events Affect the Architecture of the Self". In Simão, Lívia Mathias; Valsiner, Jaan. Otherness in Questions: Labyrinths of the Self. Greenwich, Conn.: Information Age Publishing. ISBN 9781593112325.

- Rowe, Joseph M., Jr. (1991). "Treaty of Paris of 1898". In Olson, James Stuart; Shadle, Robert. Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism. New York: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313262579.

- Ryan, Dan (2010). Admiral's Son, General's Daughter. Bloomington, Ind.: AuthorHouse. ISBN 9781452031279.

- Salvadó, Francisco J. Romero (1999). Twentieth-Century Spain: Politics and Society in Spain, 1898-1998. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 9780312216269.

- Schoonover, Thomas David (2003). Uncle Sam's War of 1898 and the Origins of Globalization. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813122823.

- Schulp, Leonard (2010). "Garrett Augustus Hobart". In Purcell, L. Edward. Vice Presidents: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 9781438130712.

- Simmons, Edwin H. (2003). The United States Marines: A History. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781591147909.

- Smith, Joseph (1995). The Spanish-American War: Conflict in the Caribbean and the Pacific, 1895-1902. New York: Longman. ISBN 9780582043008.

- Smith, Joseph (1994). "War Department Investigating Commission". In Beede, Benjamin R. The War of 1898, and U.S. Interventions, 1898-1934: An Encyclopedia. Florence, Ky.: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780824056247.

- Soltero, Carlos R. (2006). Latinos and American Law: Landmark Supreme Court Cases. Austin, Tex.: University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292713109.

- Hastedt, Glenn, ed. (2004). "Spanish-American War". Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy. New York: Facts On File. ISBN 9780816046423.

- Kazin, Michael; Edwards, Rebecca; Rothman, Adam, eds. (2011). "Spanish-American War and Filipino Insurrection". The Concise Princeton Encyclopedia of American Political History. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691152073.

- Swaine, Robert T. (2007). The Cravath Firm and Its Predecessors, 1819-1947. Clark, N.J.: Lawbook Exchange. ISBN 9781584777137.

- Sweetman, Jack (2002). American Naval History: An Illustrated Chronology of the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, 1775–Present. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781557508676.

- Symonds, Craig L. (2005). Decision at Sea: Five Naval Battles That Shaped American History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195171457.

- Trask, David F. (1996). The War With Spain in 1898. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803294295.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). "Arroyo, Puerto Rico". In Tucker, Spencer. The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099511.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). "Augustín y Dávila, Basilio". In Tucker, Spencer. U.S. Leadership in Wartime: Clashes, Controversy, and Compromise. Volume 1. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598841725.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). "Cámara y Libermoore, Manuel de la". In Tucker, Spencer. The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099511.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2013). "Expansion at Home and Abroad: Timeline". In Tucker, Spencer. Almanac of American Military History. Volume 2. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598845303.

- Tucker, Spencer, ed. (2010). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. Volume V: 1861-1918. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851096671.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2009). "Santiago de Cuba, Naval Battle of (July 3, 1898)". In Tucker, Spencer. U.S. Leadership in Wartime: Clashes, Controversy, and Compromise. Volume 1. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598841725.

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2013). "William Thomas Sampson (1840-1902)". In Tucker, Spencer. Almanac of American Military History. Volume 2. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598845303.

- Villafaña, Frank (2012). Expansionism: Its Effects on Cuba's Independence. New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9781412846561.

- Watson, Cynthia (2008). U.S. National Security: A Reference Handbook. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781598840414.

- Williams, Scott Allen (2009). Corpus Christi. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738558530.

- Wintermute, Bob A. (2009). "Round-Robin Letter". In Tucker, Spencer. The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851099511.

- Zaloga, Steve (2011). Dwight Eisenhower Leadership, Strategy, Conflict. Oxford, U.K.: Osprey. ISBN 9781849083591.

- Zimmerman, Warren (2004). First Great Triumph: How Five Americans Made Their Country a World Power. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 9780374179397.