Trellis modulation

| Passband modulation |

|---|

| Analog modulation |

| Digital modulation |

| Spread spectrum |

| See also |

In telecommunication, trellis modulation (also known as trellis coded modulation, or simply TCM) is a modulation scheme that transmits information with high efficiency over band-limited channels such as telephone lines. Gottfried Ungerboeck invented trellis modulation while working for IBM in the 1970s, and first described it in a conference paper in 1976. It went largely unnoticed, however, until he published a new, detailed exposition in 1982 that achieved sudden and widespread recognition.

In the late 1980s, modems operating over plain old telephone service (POTS) typically achieved 9.6 kbit/s by employing four bits per symbol QAM modulation at 2,400 baud (symbols/second). This bit rate ceiling existed despite the best efforts of many researchers, and some engineers predicted that without a major upgrade of the public phone infrastructure, the maximum achievable rate for a POTS modem might be 14 kbit/s for two-way communication (3,429 baud × 4 bits/symbol, using QAM).

14 kbit/s is only 40% of the theoretical maximum bit rate predicted by Shannon's theorem for POTS lines (approximately 35 kbit/s).[1] Ungerboeck's theories demonstrated that there was considerable untapped potential in the system, and by applying the concept to new modem standards, speed rapidly increased to 14.4, 28.8 and ultimately 33.6 kbit/s.

A new modulation method

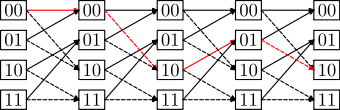

The name trellis derives from the fact that a state diagram of the technique closely resembles a trellis lattice. The scheme is basically a convolutional code of rates (r,r+1). Ungerboeck's unique contribution is to apply the parity check for each symbol, instead of the older technique of applying it to the bit stream then modulating the bits. He called the key idea mapping by set partitions. This idea groups symbols in a tree-like structure, then separates them into two limbs of equal size. At each "limb" of the tree, the symbols are further apart.

Though hard to visualize in multiple dimensions, a simple one-dimension example illustrates the basic procedure. Suppose the symbols are located at [1, 2, 3, 4, ...]. Place all odd symbols in one group, and all even symbols in the second group. (This is not quite accurate, because Ungerboeck was looking at the two dimensional problem, but the principle is the same.) Take every other symbol in each group and repeat the procedure for each tree limb. He next described a method of assigning the encoded bit stream onto the symbols in a very systematic procedure. Once this procedure was fully described, his next step was to program the algorithms into a computer and let the computer search for the best codes. The results were astonishing. Even the most simple code (4 state) produced error rates nearly one one-thousandth of an equivalent uncoded system. For two years Ungerboeck kept these results private and only conveyed them to close colleagues. Finally, in 1982, Ungerboeck published a paper describing the principles of trellis modulation.

A flurry of research activity ensued, and by 1990 the International Telecommunication Union had published modem standards for the first trellis-modulated modem at 14.4 kilobits/s (2,400 baud and 6 bits per symbol). Over the next several years further advances in encoding, plus a corresponding symbol rate increase from 2,400 to 3,429 baud, allowed modems to achieve rates up to 34.3 kilobits/s (limited by maximum power regulations to 33.8 kilobits/s). Today, the most common trellis-modulated V.34 modems use a 4-dimensional set partition—achieved by treating two two-dimensional symbols as a single lattice. This set uses 8, 16, or 32 state convolutional codes to squeeze the equivalent of 6 to 10 bits into each symbol the modem sends (for example, 2,400 baud × 8 bits/symbol = 19,200 bit/s).

Once manufacturers introduced modems with trellis modulation, transmission rates increased to the point where interactive transfer of multimedia over the telephone became feasible (a 200 kilobyte image and a 5 megabyte song could be downloaded in less than 1 minute and 30 minutes, respectively). Sharing a floppy disk via a BBS could be done in just a few minutes, instead of an hour. Thus Ungerboeck's invention played a key role in the Information Age.

See also

- Modems, for the history of various encoding modulations from 0.3 to 56 kbit/s

- Trellis diagram, in the article about convolutional codes

In popular culture

In the December 8, 1991 edition of the Dilbert comic strip, Scott Adams refers to the mere mentioning of trellis code modulation as a means for stopping a casual conversation cold.[2]

Relevant papers

- G. Ungerboeck, "Channel coding with multilevel/phase signals," IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory, vol. IT-28, pp. 55–67, 1982.

- G. Ungerboeck, "Trellis-coded modulation with redundant signal sets part I: introduction," IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 25-2, pp. 5–11, 1987.

References

- ↑ Forney, G. David; et al. (September 1984). "Efficient modulation for band-limited channels". IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications. 9: 632–647.

- ↑ "Dilbert Comic Strip".

External links

- TCM tutorial

- Oral-History:Gottfried Ungerboeck, Engineering and Technology History Wiki (IEEE Global History Network)