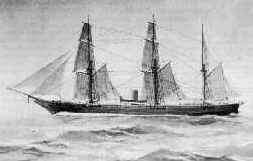

USS Wyoming (1859)

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | USS Wyoming |

| Laid down: | July 1858 |

| Launched: | 19 January 1859 |

| Commissioned: | October 1859 |

| Decommissioned: | 30 October 1882 |

| Fate: | Sold, 9 May 1892 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Screw sloop |

| Displacement: | 1,457 long tons (1,480 t) |

| Length: | 198 ft 6 in (60.50 m) |

| Beam: | 33 ft 2 in (10.11 m) |

| Draft: | 14 ft 10 in (4.52 m) |

| Propulsion: | Steam engine |

| Speed: | 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph) |

| Complement: | 198 officers and enlisted |

| Armament: |

|

The first USS Wyoming of the United States Navy was a wooden-hulled screw sloop that fought on the Union side during the American Civil War. Sent to the Pacific Ocean to search for the CSS Alabama, Wyoming eventually came upon the shores of Japan and engaged Japanese land and sea forces. On 16 July 1863, Wyoming won the first-ever United States naval victory over Japan in the Naval battle of Shimonoseki.

Service history

The ship was laid down at the Philadelphia Navy Yard in July 1858, launched on 19 January 1859, sponsored by Mary Florida Grice, and commissioned in October 1859, Commander John K. Mitchell in command. She was named for the Wyoming Valley in Pennsylvania, not the state of Wyoming which did not yet exist.

West Coast, 1859–1862

Wyoming soon sailed via Cape Horn for the Pacific and arrived off the coast of Nicaragua in April 1860. There, she relieved Levant and operated along the Pacific coast of the United States and Central America into the spring of 1861. During that time, she participated in the search for Levant when that warship disappeared in the late autumn of 1860.

The outbreak of the Civil War found Wyoming at San Francisco, California, preparing for another cruise. She was instructed to remain in the vicinity of the Golden Gate to protect mail steamers operating off the California coast, but CDR Mitchell — a naval officer of Southern origin and persuasion — defied his orders and took his ship to Panama instead.

Mitchell's flagrant disobedience cost him his command and also resulted in his dismissal from the service. As a result, Wyoming came under the temporary command of her executive officer, Lt. Francis K. Murray, on 4 July 1861. While returning to Monterey, California, Wyoming was plagued by mishaps. First, her bottom struck a coral head off La Paz, Baja California Sur, and was pulled free only after three days aground during which she lost her false keel. She then ran short of coal and arrived at Monterey with empty bunkers.

Wyoming subsequently shifted to San Francisco where, on 9 August, she received a new commanding officer, Commander David McDougal. The warship then proceeded to the coast of Lower California to protect American whaling interests against possible incursions by Confederate cruisers. After that service, she operated in South American waters into 1862.

Far East, 1862–1863

Following repairs at Mare Island, Wyoming received orders — dated 16 June 1862 — to proceed immediately to the Far East in search of "armed piratical cruisers fitted out by the rebels" and soon headed west, bound for the Orient.

Word of the Union ship's subsequent appearance in Far Eastern waters spread fast and far. In the Sunda Strait, off Java, Captain Raphael Semmes, the commanding officer of Confederate cruiser Alabama, learned from an English brig of Wyoming's arrival in the East Indies; and a Dutch trader later confirmed this report. On 26 October, Semmes wrote confidently in his journal that "Wyoming is a good match for this ship," and "I have resolved to give her battle. She is reported to be cruising under sail — probably with banked fires — and anchors, no doubt, under Krakatoa every night, and I hope to surprise her, the moon being near its full."

Although in their search for each other, Wyoming and Alabama unknowingly came close to each other, they never met; and it would be up to another Union warship, the sloop Kearsarge, to destroy the elusive Confederate raider. Yet, despite being unsuccessful in tracking down Confederate cruisers, Wyoming did render important service to uphold the honor of the American flag in the Far East the following year, 1863.

Ordered to Philadelphia that spring — after what had been a largely fruitless cruise — Wyoming was in the midst of preparations to leave the East Indies Station when an event occurred that changed her plans.

The Battle of the Straits of Shimonoseki, 1863

In May 1863, Wyoming was stationed at Yokohama as a show of force, standing by to protect American lives and property during an outbreak of anti-foreign agitation in Japan. Nevertheless, that agitation continued into the early summer months, as the sonnō jōi movement grew in strength with increasing resentment by the Japanese to the terms of the recent unequal treaties signed with the western powers. Emperor Kōmei issued a decree setting 25 June 1863 as the date for the expulsion of all aliens from Japan.

Although the Tokugawa shogunate was largely powerless to force compliance with this directive, the powerful pro-sonnō jōi daimyō of Chōshū Domain, the Mōri Takachika took the decree literally and decided to attack foreign ships passing through the Straits of Shimonoseki, which the domain regarded as part of its territory.

At one o'clock on morning of 26 June, two armed vessels of Chōshū Domain attacked the American merchantman Pembroke, bound for Nagasaki and Shanghai, as she lay anchored in the Strait of Shimonoseki. Pembroke suffered no casualties; got underway; and moved out of danger, escaping via Bungo Strait and continuing her voyage for Shanghai, post-haste, without making her scheduled stop at Nagasaki.

Word of the incident did not reach Yokohama from Japanese sources until 10 July. That evening, mail from Shanghai brought "authentic information" confirming the Japanese report. The United States Minister in Japan, Robert H. Pruyn, sent for the Minister of Foreign Affairs for the Japanese government and informed him — in the presence of Comdr. McDougal — of the gravity of the situation, stressing that an insult to the American flag was a serious matter. After being told by Pruyn that the United States government would demand satisfaction and expect a statement from the Japanese concerning the offense, the Japanese diplomat begged that the Americans do nothing until his government at Edo took action.

After the Japanese left, McDougal told Pruyn that he had decided to proceed instantly to the Shimonoseki Strait to seize and, if necessary, to destroy, the offending vessels. The two men agreed that lack of punitive action would encourage further anti-foreign incidents.

Accordingly, Wyoming prepared for sea. At 4:45 a.m. on 13 July, CDR McDougal called all hands; and the sloop got underway 15 minutes later, bound for the strait. After a two-day voyage, Wyoming arrived off the island of Himeshima on the evening of 15 July and anchored off the south side of that island.

At five o'clock the following morning, Wyoming weighed anchor and steamed toward the Strait of Shimonoseki. She went to general quarters at nine, loaded her pivot guns with shell, and cleared for action. The warship entered the strait at 10:45 and beat to quarters. Soon, three signal guns boomed from the landward, alerting the Chōshū coastal artillery batteries and warships of Wyoming's arrival.

At about 11:15, after being fired upon from the shore batteries, Wyoming hoisted her colors and replied with her 11-inch pivot guns. Momentarily ignoring the batteries, McDougal ordered Wyoming to continue steaming toward a bark, a steamer, and a brig at anchor off the town of Shimonoseki. Meanwhile, four shore batteries took the warship under fire. Wyoming answered the Japanese cannon "as fast as the guns could be brought to bear" while shells from the shore guns passed through her rigging.

Wyoming then passed between the brig and the bark on the starboard hand and the steamer on the port, steaming within a pistol shot's range. One shot from either the bark or brig struck near Wyoming's forward broadside gun, killing two men and wounding four. Elsewhere on the ship, a Marine was struck dead by a piece of shrapnel.

Wyoming, in hostile territory, then grounded in uncharted waters shortly after she had made one run past the forts. The Japanese steamer, in the meantime, had slipped her cable and headed directly for Wyoming — possibly to attempt a boarding. The American man-of-war, however, managed to work free of the mud and then unleashed her 11-inch Dahlgren guns on the enemy ship, hulling and damaging her severely. Two well-directed shots exploded her boilers and, as she began to sink, her crew abandoned the ship.

Wyoming then passed the bark and the brig, firing into them steadily and methodically. Some shells were "overs" and landed in the town ashore, setting it on fire. As Comdr. McDougal wrote in his report to Gideon Welles on 23 July, "the punishment inflicted (upon the daimyo) and in store for him will, I trust, teach him a lesson that will not soon be forgotten."

After having been in combat for a little over an hour, Wyoming returned to Yokohama. She had been hulled 11 times, with considerable damage to her smokestack and rigging. Her casualties had been comparatively light: four men killed and seven wounded — one of whom later died. Significantly, Wyoming had been the first foreign warship to take offensive action to uphold treaty rights in Japan.

Hunting the raiders, 1863–1864

However, the ship's projected return to Philadelphia did not materialize due to the supposed continued presence of Alabama in Far Eastern waters. She repaired her damages, resumed the search and sailed to the Dutch East Indies. She subsequently voyaged to Christmas Island, examining it to determine whether or not it was used as a supply base for "the use of rebel cruisers." Finding the island uninhabited and the report of its use as a supply base unfounded, Wyoming returned to Anjer, Java, where McDougal found out, to his surprise, that Alabama had passed the Sunda Strait on 10 November — only a day after Wyoming had sailed for Christmas Island. At noon that day, Alabama and Wyoming had been only 25 miles apart.

Writing from Batavia on 22 November, McDougal later reported that Wyoming had scoured the waters of the East Indies, visiting "every place in this neighborhood where she (Alabama) would likely lay in case she intended to remain in this region." Although acknowledging that the condition of Wyoming's boilers prevented a heavy pressure of steam from being carried, McDougal promised to make every effort in his power to find and capture Alabama.

Wyoming then cruised to Singapore in search of the Confederate raider, but found nothing, and continued on to the Dutch settlement of Rhio, near Sunda Strait. She subsequently sailed north, putting into Cavite, Luzon, in the Philippine Islands, on Christmas Eve. There, through the courtesy of the Spanish Navy, Wyoming underwent much-needed boiler repairs and coaled. She then sailed for Hong Kong and Whampoa, China.

Wyoming continued her search for the elusive Alabama into February 1864. She sailed to Foochow, China, to protect American interests and proceeded thence, via Hong Kong, to the East Indies. When the sloop-of-war reached Batavia, however, CDR McDougal found that there was now no alternative but to return to the United States for repairs, because the ship's boilers were in such poor condition. Accordingly, Wyoming began her long-delayed return voyage to the United States, via Anjer, the Cape of Good Hope, St. Helena, and St. Thomas. After a voyage of almost three months, she arrived at the Philadelphia Navy Yard on 13 July 1864; having completed a circumnavigation of the globe begun when she left that port following her commissioning.

The presence of CSS Florida off the East Coast, however, meant another change in plans for the weary Wyoming. Commodore Cornelius Stribling, Commandant of the Philadelphia Navy Yard, ordered the newly arrived screw sloop to sea to search for Florida. "It is with regret that I send you on this service," Stribling wrote McDougal, "After so long a cruise, and one in which you have rendered such important service, yourself, officers and crew, were entitled to a respite from active service; but the great importance of capturing the rebel privateer will, I hope, be an incentive to all under your command cheerfully to perform this service."

Although Wyoming required extensive repairs, she nevertheless sailed. As events proved, however, Wyoming's machinery — so long from repairs in an American Navy Yard — proved unequal to the strain. For five days, the ship attempted to carry out the orders given her — contending with fresh northeast winds and a head sea — but returned to Philadelphia on 19 July, due to a leaky boiler. She was decommissioned on 23 July for a complete overhaul.

East Indies Station, 1865–1868

Recommissioned on 11 April 1865, Comdr. John P. Bankhead in command, Wyoming proceeded to the East Indies Station, via Cape Horn, and reached Singapore on 25 September 1865, in time to participate in the search for CSS Shenandoah, a Confederate raider which remained at sea for one month after the end of the Civil War. Following service on the East Indies Station into 1866, the screw sloop-of-war was made part of the Asiatic Squadron with that unit's establishment in 1867.

Sailing from Yokohama on 28 April 1867, Wyoming headed for the island of Formosa (Taiwan). On 13 June, she participated in a punitive expedition against Formosan natives who had murdered the crew of the American merchant bark Rover that had been wrecked off the coast of Formosa a short time before. During that action, she sent a landing party ashore in company with one from the sloop Hartford.

Subsequently returning to the United States having performed her last service in the Far East, Wyoming was decommissioned on 10 February 1868 and placed "in ordinary" at Boston, Massachusetts. After extensive repairs at Portsmouth Navy Yard, during 1870 and into 1871, Wyoming was recommissioned on 14 November 1871, Comdr. John L. Davis in command.

North Atlantic Station, 1872–1878

From 1872 to 1874, Wyoming operated on the North Atlantic Station. Her ports of call included Havana, Cuba; Key West, Florida.; Aspinwall, Panama; Santiago, Cuba; Kingston, Jamaica; San Juan, Puerto Rico; Key West; Hampton Roads, Va.; and New Bedford, Mass. After that tour of duty, cruising and "showing the flag" in the West Indies and Gulf of Mexico, Wyoming was decommissioned at the Washington Navy Yard on 30 April 1874 and remained laid up there for the next two years.

In 1876, the Wyoming was depolyed to the Potomac river in order to defend Washington DC at rumors of an invasion by Southern separatists after the controversial election between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel J. Tilden.

The veteran screw sloop-of-war became the receiving ship at Washington in 1877 and apparently served in that capacity into early the following year. Recommissioned on 20 November 1877, Wyoming left Washington, loaded articles for the Paris Exposition, and departed the East Coast of the United States on 6 April 1878, bound for France. After discharging the cargo at Le Havre, France, the ship visited Rouen, France, and Southampton, England, before she departed the latter port on 25 June and headed for the United States. She reached Norfolk on 22 August, shifted to Washington in mid-September, and to New York in early November, before she sailed on 26 November for the European Station.

European Station, 1878–1881

Wyoming reached Villefranche, France, near the port of Nice, on Christmas Eve 1878 and remained there into 1879 before getting underway for Smyrna on 24 January 1879. Wyoming remained in the Mediterranean into November 1880, touching at many of the more famous ports in that historic body of water — and in the Black Sea — before heading home late in 1880.

Wyoming returned to the United States in early 1881, arriving at Hampton Roads on 21 May. She sailed for Beaufort, S.C., on 15 June and thence proceeded to Annapolis, Md.

Naval Academy, 1882–1892

Decommissioned on 30 October 1882 and turned over to the Superintendent of the Naval Academy, Wyoming spent the next decade employed as a practice ship for midshipmen. Later taken to Norfolk, Va., she was sold at the port on 9 May 1892 to E. J. Butler, of Arlington, Massachusetts.

See also

- List of sloops of war of the United States Navy

- Confederate States Navy

- Union Navy

- Bibliography of early American naval history

References

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.