Urse d'Abetot

| Urse d'Abetot | |

|---|---|

The Château de Tancarville in Normandy. Urse was a tenant of the lords of Tancarville. | |

| Sheriff of Worcestershire | |

|

In office c. 1069 – 1108 | |

| Preceded by | Cyneweard of Laughern[1] |

| Succeeded by | Roger d'Abetot |

| Royal constable | |

|

In office after 1087 – 1108 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

c. 1040 Normandy |

| Died | 1108 |

| Spouse(s) | Alice |

| Children | Roger d'Abetot, Emmeline |

Urse d'Abetot (sometimes Urse of Abetot,[2] Urse de Abetot,[3] Urse d'Abitot[4] or Urse of Abitôt[5]) (c. 1040 – 1108) was a Norman as well as a medieval Sheriff of Worcestershire and royal official under Kings William I, William II and Henry I. He was a native of Normandy and moved to England shortly after the Norman Conquest of England, and was appointed sheriff in about 1069. Little is known of his family in Normandy, who were not prominent. Although Urse's lord in Normandy was present at the Battle of Hastings, there is no evidence that Urse took part in the invasion of England in 1066.

Urse built a castle in the town of Worcester, which encroached on the cathedral cemetery there, earning him a curse from the Archbishop of York. Urse helped to put down a rebellion against King William I in 1075, and quarrelled with the Church in his county over the jurisdiction of the sheriffs. He continued in the service of William's sons after the king's death, and was appointed constable under William II and marshal under Henry I. Urse was known for his acquisitiveness, and during William II's reign was considered second only to Ranulf Flambard, another royal official, in his rapacity. Urse's son succeeded him as sheriff but was subsequently exiled, thus forfeiting the office. Through his daughter, Urse is an ancestor of the Beauchamp family, who eventually became Earls of Warwick.

Background

Norman Conquest of England

On 5 January 1066 Edward the Confessor, King of England, died. Edward's lack of children meant there was no clear legitimate successor, leading eventually to a succession dispute. Some medieval writers state that shortly before Edward's death he named his brother-in-law, Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, as his heir. Others claim that Edward had promised the throne to his cousin, William, Duke of Normandy, a powerful autonomous ruler in northern France. Harold, the most powerful English noble, took the initiative and was crowned king on 6 January. William, lacking Harold's proximity to the centres of English royal government, gathered troops and prepared an invasion fleet. He invaded England in October, and subsequently defeated and killed Harold at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066. William was crowned on Christmas Day at Westminster, becoming William I.[6]

Between his coronation and 1071, William consolidated his hold over England, defeating a number of rebellions that arose particularly in the north and west of the country. Immediately after Hastings, only those English noblemen who fought in the battle lost their lands,[7] which were distributed to Normans and others from the continent who had supported William's invasion.[8] The rebellions of the years 1068 to 1071 led to fresh confiscations of English land, again distributed to William's continental followers.[9] By 1086, when William ordered the compilation of Domesday Book to record landholders in England, most of the native English nobility had been replaced by Norman and other continental nobles.[10]

Sources

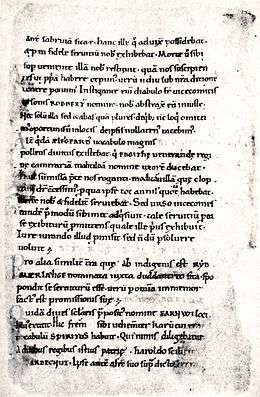

The main sources for Urse's life are English documents such as charters and writs which mention his activities.[11] Often these are contained in collections of such documents, known as cartularies, which were assembled by monasteries and cathedral chapters to document their landholdings. Cartularies frequently contain documents from landholders surrounding a monastery,[12] which is the case with many of the documents mentioning Urse.[13] Other sources of information on Urse are Domesday Book, which mentions his landholdings in 1086, and a number of chronicles, including William of Malmesbury's Gesta pontificum Anglorum, Florence of Worcester's Chronicon ex chronicis, and Hemming's Cartulary, a mixed chronicle and cartulary from Worcester Cathedral.[11] There are also mentions of Urse in Norman sources, such as charters for Saint-Georges de Boscherville Abbey.[13]

Family and early life

Urse came from an undistinguished family,[14] and made his way on military reputation.[15] He was probably born in about 1040, but the exact date is unknown.[11] He was from St Jean d'Abbetot in Normandy, where his family had lands,[13] and where he himself was a tenant of the lords of Tancarville.[16] Other tenants of the Tancarville lords included Robert d'Abetot and his wife Lesza, who held lands close to St Jean d'Abbetot in the early 12th century; despite the name, it is not certain that Robert d'Abetot was related to Urse.[17] Urse had a brother usually called Robert Despenser,[11] sometimes known as Robert fitz Thurstin,[18] who also became a royal official.[11] The historian Emma Mason suggested that Urse may have been a nickname rather than a forename, perhaps given on account of his tenacious temperament.[19][lower-alpha 1] Urse's usual last name derives from his ancestral village in Normandy. His brother's usual last name of Despenser derives from his office, that of dispenser, in the royal household.[11]

Ralph, the Lord of Tancarville during the reign of King William I of England and Urse's overlord in Normandy, fought at the Battle of Hastings, but there is no evidence that Urse himself was present.[16][lower-alpha 2] He is probably the same person as the "Urse d'Abetot" who was a witness to a charter of William before the invasion of England. The historian Lewis Loyd refers to Urse as "in origin a man of no importance who made his way as a soldier of fortune".[3]

Service to William I

.png)

Sheriff of Worcester

Urse arrived in England after Hastings, but it is unknown if his brother Robert arrived with him or separately.[17] Urse was appointed Sheriff of Worcestershire some time after the Norman Conquest of England,[11] probably in about 1069,[13] part of the wholesale replacement of English royal officials with Norman and other immigrants that took place in the early part of William's reign.[23] As sheriff, Urse was responsible for collecting taxes and forwarding them to the treasury, and was empowered to raise armies if rebellion or invasion threatened. The sheriff presided over the shire court, and was accountable for the shire's annual payments to the king.[24] During the reigns of William the Conqueror and his sons, the office of sheriff was a powerful one, as it did not share power with any other official in the shire, unless there was an earl in overall control.[25][26] Because of their control of the courts for the hundreds – which were subdivisions of the shire[27] – sheriffs had opportunities for patronage and also had a large say in who became members of the hundred and shire court juries.[26] The death of Edwin, Earl of Mercia, who held power in Worcestershire until his death in 1071 during a rebellion against William, allowed Urse to accumulate more authority in Worcestershire, as Edwin was the last Earl of Mercia.[1]

Urse also oversaw the construction of a new castle at the town of Worcester,[15] although nothing now remains of the castle.[28] Worcester Castle was in place by 1069, its outer bailey built on land that had previously been the cemetery for the monks of the Worcester cathedral chapter.[1] The motte of the castle overlooked the river, just south of the cathedral.[29] Although Urse had control of the castle after it was built, by 1088 he had lost it to the bishops of Worcester.[1]

In 1075, three earls rebelled, for reasons unknown,[30] and sought aid from the King of Denmark, Sweyn II Estridsson, who had a distant claim to the English throne.[31] Among the rebels was Roger de Breteuil, the Earl of Hereford, whose lands neighboured those of Urse. Along with Bishop Wulfstan of Worcester, Abbot Æthelwig of Evesham, and Walter de Lacy, Urse prevented de Breteuil from crossing the River Severn.[32] Urse's actions kept the rebels from seizing control of the Severn Valley[33] and joining up with the other English rebels, Waltheof, the Earl of Northumbria, and Ralph de Gael, the Earl of Norfolk.[31] Urse and the magnates fighting alongside him, in addition to their obvious desire to suppress rebellion, had an interest in defeating de Breteuil, as he was the most powerful lord in the area.[19] De Breteuil was caught, tried, and imprisoned for life,[34] increasing the power of his rivals.[19]

Urse, along with his contemporaries, benefited from the increasing power wielded by the sheriffs. Although royal officials, including the sheriffs, had been appropriating ecclesiastical lands since the late 10th century, in the immediate years after the Norman Conquest churchmen complained about the increased amount of land seized by the sheriffs. Urse received his share of complaints, but he was part of a wider trend during the early years of William I's reign. The appropriation of land led to an increase in the recording of rights and possessions not only by clergy but also by laymen, culminating in the recording of all possessions and the rights held by the king over them in the Domesday Survey of 1086.[35] This behaviour was not limited to the sheriffs, as other nobles were also accused in contemporary chronicles of appropriating land from churches and from native Englishmen.[36]

Disputes with Wulfstan and Ealdred

During the reign of William I, Urse became involved in a dispute with Bishop Wulfstan over the rights of the sheriff in the lands of the diocese.[4] By the time of Domesday Book in 1086, Urse's powers as sheriff had been excluded from the Oswaldslaw, the area of Worcestershire controlled by the bishops of Worcester. Domesday Book records that the Oswaldslaw was regarded as an immunity, exempt from judicial actions by royal officials. Urse complained that this immunity reduced his income, but this did not affect the outcome of his dispute with Wulfstan, who prevailed. Although Wulfstan claimed that the immunity dated from before the Conquest, it actually owed its existence to the ability of the bishop to fill the shire court with his supporters, and thus influence the findings of the court.[37]

Urse was also involved in a dispute between Wulfstan and Evesham Abbey over lands in Worcestershire as, after the Conquest, Urse acquired the lands of Azur, a kinsman of an earlier Bishop of Worcester, Beorhtheah. Azur had originally leased the lands from the diocese, but after Urse confiscated the lands, the sheriff did not return the lands to the bishop, and instead kept them for himself.[38] The Worcester monk Hemming recorded the loss of the lands to Urse in Hemming's Cartulary, a cartulary written about 1095 recording lands and charters belonging to the diocese of Worcester.[39][40] Hemmings' Cartulary mentions not just Azur's lands, but others at Acton Beauchamp, Clopton, and Redmarley as taken from the diocese of Worcester by Urse.[39] After Abbot Æthelwig's death, Urse also acquired lands that Æthelwig had seized through less than legal means, when William I's half-brother Odo of Bayeux, the Bishop of Bayeux, presided at the lawsuit brought to determine the ownership of the lands. Odo gave a number of the disputed estates to Urse during the course of the lawsuit.[41]

The 12th-century chronicler William of Malmesbury records a story, in which shortly after Urse was appointed sheriff, he encroached on the cemetery of the cathedral chapter of Worcester Cathedral. Ealdred, the Archbishop of York, pronounced a rhyming curse on Urse, declaring "Thou are called Urse. May you have God's curse."[42][lower-alpha 3] Ealdred had been Bishop of Worcester before becoming archbishop, and still retained an interest in the diocese.[45] Gerald of Wales, a late 12th- and early 13th-century writer, wrote that Wulfstan uttered the curse after Urse had attempted to have Wulfstan deposed as bishop. Gerald goes on to relate that Wulfstan stated he would only relinquish his episcopal staff to the king who had granted it, William I's predecessor, Edward the Confessor. Gerard then reports that Wulfstan proceeded to work a miracle at Edward's tomb, a miracle so impressive that King William confirmed Wulfstan in his episcopate. Although Urse did not succeed in removing Wulfstan, and although there are certainly embellishments added in Gerald's story, it is clear that Urse and Wulfstan were the main powers in Worcestershire, and were thus great rivals.[46]

The Archbishop's curse had no discernible effect, either on Urse's career or the castle.[43] Other chroniclers record that Urse stole monastic lands, including some from Evesham Abbey. Urse gained a reputation for greed and avarice, especially with regard to church lands.[47] Great Malvern Priory, however, claimed him as a founder in a 14th-century document.[11]

Domesday lands

In 1086, the Domesday Survey documents that while the majority of Urse's lands were in Worcestershire, he also held land in Warwickshire, Herefordshire, and Gloucestershire. His lands in Warwickshire were held directly from the king, as a tenant-in-chief, while others were held as an under-tenant of others who had their lands directly from the king. Urse's lands in Herefordshire likewise were held as a mixture of tenant-in-chief and sub-tenant, as was also the case in Gloucester. Of the lands that Urse held in Worcestershire, he held them both directly from the king and from the Bishop of Worcester.[48] Domesday also records that the revenue that Urse was responsible for as sheriff was £128 and 4 shillings from Worcestershire. This was just the amount due for the royal estates in Worcester, as Urse was also responsible for payments of £23 and 5 shillings for the royal lands in the Borough of Worcester, £17 as profits on the shire and hundred courts with an additional £16 or a hunting hawk, specifically a "Norway hawk"; also due from the courts. Urse also had to pay the queen £5 plus £1 additional for a "sumpter horse". All of these payments were guaranteed by Urse, who had to make up any shortfall.[49]

Domesday makes it obvious that Urse was the most powerful layman in Worcester, and the only person who could contest his power in the county was the Bishop of Worcester. The power struggle continued into the 12th century, as Urse's descendants still contested the bishops. Only one other layman is recorded as having a castle in Worcestershire in Domesday, and he held much less land than Urse.[1]

Service to William II and Henry I

After the death of King William I of England, Urse continued to serve William's sons and successors, Kings William II Rufus and Henry I.[11] While William I granted the duchy of Normandy to his eldest son, Robert Curthose, England went to his second surviving son, William Rufus. Henry (later Henry I), the youngest son, was given a sum of money.[50] In 1088, shortly after William Rufus became king, Urse was present at the trial of William de St-Calais, Bishop of Durham,[51] and is mentioned in De Iniusta Vexacione Willelmi Episcopi Primi, a contemporary account of the trial.[52] During William I's reign, Urse had served the king mainly as a regional official, but during William II's reign Urse began to take a broader role in the kingdom as a whole.[41] Urse became a constable in the king's household for both William II[53] and Henry I,[54] and under William II, he ascended to the office of marshal.[55]

Urse was an assistant to William II's main minister, Ranulf Flambard,[56] and frequently served as a royal judge. The historian Emma Mason argues that Urse, along with Flambard, Robert Fitzhamon, Roger Bigod, Haimo the dapifer, or seneschal, and Eudo, another dapifer, were the first recognizable barons of the Exchequer.[51] During his absence from England, the king addressed a number of writs to Urse, along with Haimo, Eudo, and Robert Bloet, ordering them to enforce William's decisions in England. The historian Francis West, who studied the office of the justiciarship, asserts that Haimo, Eudo, and Urse, along with Flambard, could be considered the first English justiciars.[57]

Urse's estates grew under William II,[58] partly as a result of the inheritance of some of the lands of his brother, Robert Despenser,[59][lower-alpha 4] who died about 1097.[11] Later, Urse consolidated his holdings by exchanging some of Robert's lands in Lincolnshire with Robert de Lacy for lands closer to his base in Worcestershire.[41] Urse d'Abetot gained and passed to his heirs an estate that later became the Barony of Salwarpe, Worcestershire.[60]

William II died in a hunting accident on 2 August 1100. His younger brother Henry immediately rode to Winchester and had himself crowned king before his elder brother, Robert Curthose, could claim the throne.[61] Although Urse did not attest the charter Henry issued after he seized the throne, Urse was at court shortly afterwards.[62] When Robert Curthose invaded England in 1101 in an attempt to take the English throne, Urse supported Henry.[63] Urse was present at the court held at Winchester on 2 August 1101, when a peace treaty was ratified between the brothers.[64] During Henry's reign, the king regranted Urse's lands to him, with some of them now granted as a tenant-in-chief when previously Urse had held those lands as an under-tenant, and not directly from the king.[65] Urse's lands at Salwarpe were previously held by Roger of Montgomery, but were granted to Urse as a direct tenant of the king when Roger's son, Robert of Belesme, was outlawed in 1102.[66] Urse continued to attest many of Henry's charters until 1108,[67] although he did not use the title of "constable" in those charters.[68]

Sometime between May and July 1108, Henry addressed a writ to Urse and the Bishop of Worcester from Reading. The royal document commanded the sheriff not summon the shire and hundred courts to locations different than customary nor that he summon them on dates other than those normal for such courts. From this, the historian Judith Green speculates that Urse had been summoning these courts at unusual times and then fining those who did not attend. The king specifically commanded that this procedure stop and then went on to detail the various courts which would hear what types of cases and the type of procedure that could be used in what type of case.[69]

Death and legacy

Urse died some time in 1108. Little is known of his wife, Alice, whose death is unrecorded.[lower-alpha 5] Urse was succeeded as sheriff by his son Roger d'Abetot, who was exiled in about 1110 and forfeited the office of sheriff. Roger's successor, Osbert d'Abetot, was probably Urse's brother. Urse also had a daughter, probably named Emmeline, who married Walter de Beauchamp. Walter succeeded to Urse's lands after Roger's exile.[11] A charter for Saint-Georges de Boscherville Abbey may indicate that Urse had a second son, named Robert.[13] Urse may also have had another daughter, who married Robert Marmion, as some of Urse's estates went to Marmion's family and others to the Beauchamps.[11][lower-alpha 6]

Urse earned a reputation for extortion and financial exactions. During the reign of William II, he was considered second only to the king's minister Ranulf Flambard in his rapacity.[70] The first mention of his exactions is in Hemming's Cartulary. Further details were given by the medieval chroniclers William of Malmesbury and Gerald of Wales, both of whom relate Ealdred's curse.[40] His exactions were also mentioned in Domesday Book, where an entry in the survey for Gloucestershire noted that his oppression prevented the inhabitants of Sodbury so much that they were unable to pay their customary rents.[71] He intimidated the monks of the Worcester cathedral chapter into granting him a lease of two of their estates, Greenhill and Eastbury.[72] Urse was one of a new breed of royal official, one who was not opposed to royal power but rather welcomed it, as it helped his own position.[19][33]

Through his daughter, he is an ancestor of the Beauchamp family of Elmley in Worcestershire, a scion of which, William de Beauchamp, became Earl of Warwick.[73] It is likely that the Beauchamp family's symbol, a bear, derives from their relationship to Urse.[40]

Notes

- ↑ This would have been a play on the meaning of the Latin word ursa, which is "bear".[11]

- ↑ Although many Victorian works claimed that Urse was at Hastings, due to his being listed on the Battle Abbey Roll as well as an inscribed plaque in a church at Dives,[20][21] this information is of a late date and current historical research has ruled out many of the names formerly listed as being with William the Conqueror at Hastings.[22]

- ↑ William of Malmesbury recorded the curse in Latin, but David Bates translates it this way. Other, more archaizing translations include "Hattest thu Urs? Have thu Godes kurs."[43] and "Hattest ðu Urs, haue ðu Godes kurs".[44]

- ↑ These, unlike Urse's lands, were not concentrated around Worcestershire, and stretched from Worcestershire to the North Sea.[17]

- ↑ Alice at one point is styled vicecomitissa, the feminine form of vicecomes, the Latin word for the English office of sheriff as well as the more hereditary Norman office of viscount; Mason argues therefore that this style indicates Urse envisaged his position as sheriff as something more akin to a Norman viscount than traditional Anglo-Saxon sheriff.[19]

- ↑ Or the Marmion connection may have been from a daughter of Robert Despenser, instead.[17]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 Williams "Introduction" Digital Domesday "Norman Settlement" section

- ↑ Barlow William Rufus p. 72

- 1 2 Loyd Origins of Some Anglo-Norman Families pp. 1–2

- 1 2 Brooks "Introduction" St Wulfstan and His World p. 3

- ↑ Hollister "Henry I and the Anglo-Norman Magnates" Proceedings of the Battle Conference II p. 95

- ↑ Huscroft Ruling England pp. 9–19

- ↑ Stafford Unification and Conquest pp. 101–103

- ↑ Williams English and the Norman Conquest pp. 10–11

- ↑ Huscroft Ruling England pp. 57–61

- ↑ Huscroft Ruling England p. 81

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Round and Mason "Abetot, Urse d'" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ↑ Coredon Dictionary of Medieval Terms and Phrases p. 61

- 1 2 3 4 5 Keats-Rohan Domesday People p. 439

- ↑ Barlow William Rufus pp. 188–189

- 1 2 Barlow William Rufus p. 152

- 1 2 Green Aristocracy p. 33

- 1 2 3 4 Mason "Magnates, Curiales and the Wheel of Fortune" Proceedings of the Battle Conference II p. 135

- ↑ Barlow William Rufus p. 141

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mason "Magnates, Curiales and the Wheel of Fortune" Proceedings of the Battle Conference II p. 137

- ↑ Appleton "Who Was Urso d'Abitot?" Miscellanea Genealogica Et Heraldica: Fourth Series

- ↑ Burke The Roll of Battle Abbey p. 4

- ↑ Lewis "Companions of the Conqueror" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ↑ Thomas Norman Conquest p. 60

- ↑ Huscroft Ruling England p. 89

- ↑ Saul Companion to Medieval England pp. 274–275

- 1 2 Mason "Administration and Government" Companion to the Anglo-Norman World p. 153

- ↑ Coredon Dictionary of Medieval Terms and Phrase p. 159

- ↑ Pettifer English Castles p. 280

- ↑ Holt "Worcester in the Time of Wulfstan" St Wulfstan and His World pp. 132–133

- ↑ Huscroft Ruling England p. 62

- 1 2 Douglas William the Conqueror pp. 231–232

- ↑ Williams English and the Norman Conquest p. 60 footnote 67

- 1 2 Prestwich "Military Household" English Historical Review p. 22

- ↑ Bates William the Conqueror pp. 180–181

- ↑ Stafford Unification and Conquest p. 107

- ↑ Fleming Kings & Lords p. 192

- ↑ Williams "Cunning of the Dove" St Wulfstan and His World p. 37

- ↑ Williams "Cunning of the Dove" St Wulfstan and His World pp. 33–35

- 1 2 Dyer "Bishop Wulfstan and His Estates" St Wulfstan and His World pp. 148–149

- 1 2 3 Mason "Legends of the Beauchamps' Ancestors" Journal of Medieval History pp. 34–35

- 1 2 3 Mason "Magnates, Curiales and the Wheel of Fortune" Proceedings of the Battle Conference II p. 136

- ↑ Quoted in Bates William the Conqueror p. 153

- 1 2 Brooks "Introduction" St Wulfstan and His World p. 15

- ↑ Wormald "Oswaldslow" St Oswald of Worcester p. 125

- ↑ Mason "St Oswald and St Wulfstan" St Oswald of Worcester pp. 279–281

- ↑ Mason "Magnates, Curiales and the Wheel of Fortune" Proceedings of the Battle Conference II pp. 136–137

- ↑ Chibnall Anglo-Norman England p. 32

- ↑ Alecto Historical Editions Digital Domesday

- ↑ Williams "Introduction" Digital Domesday "Shire Officials" section

- ↑ Huscroft Ruling England p. 64

- 1 2 Mason William II p. 75

- ↑ Offler "Tractate" English Historical Review p. 337

- ↑ Barlow William Rufus p. 95

- ↑ Green Government p. 35

- ↑ Barlow William Rufus p. 202

- ↑ Hollister Henry I pp. 363–364

- ↑ West Justiciarship pp. 11–13

- ↑ Hollister Henry I p. 171

- ↑ White "King Stephen's Earldoms" Transactions p. 71 and footnote 1

- ↑ Mooers "Familial Clout" Albion p. 274

- ↑ Huscroft Ruling England p. 68

- ↑ Green Government p. 169 footnote 137

- ↑ Hollister Henry I p. 133

- ↑ Hollister "Anglo-Norman Civil War" English Historical Review p. 329

- ↑ Newman Anglo-Norman Nobility p. 117

- ↑ Sanders English Baronies pp. 75–76

- ↑ Newman Anglo-Norman Nobility pp. 183–184

- ↑ Cronne and Johnson "Introduction" Regesta Regum Anglo-Normannorum p. xvi

- ↑ Green Henry I pp. 115–116

- ↑ Southern "Ranulf Flambard" Transactions of the Royal Historical Society pp. 110–111

- ↑ Roffe Decoding Domesday p. 69 footnote 34

- ↑ Fleming Kings & Lords pp. 202–203

- ↑ Mason "Legends of the Beauchamps' Ancestors" Journal of Medieval History p. 25

References

- Alecto Historical Editions, ed. (2003). The Digital Domesday: Silver Edition (digital CD-ROM). Editions Alecto (Domesday), Ltd. ISBN 1-871118-26-3.

- Appleton, Lewis (2001). "Who was Urso D'Abitot?". In Bannerman, W. Bruce. Miscellanea Genealogica Et Heraldica: Fourth Series (Reprint of a 1906–1914 journal series ed.). Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1-4021-9406-4.

- Barlow, Frank (1983). William Rufus. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-04936-5.

- Bates, David (2001). William the Conqueror. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1980-3.

- Brooks, Nicholas (2005). "Introduction". In Brooks, Nicholas; Barrow, Julia. St. Wulfstan and His World. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. pp. 1–21. ISBN 0-7546-0802-6.

- Burke, John Bernard (1848). The Roll of Battle Abbey, Annotated. London: Edward Churton. OCLC 187033245.

- Chibnall, Marjorie (1986). Anglo-Norman England 1066–1166. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0-631-15439-6.

- Coredon, Christopher (2007). A Dictionary of Medieval Terms & Phrases (Reprint ed.). Woodbridge, UK: D. S. Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84384-138-8.

- Cronne, H. A. & Johnson, Charles (1956). "Introduction". In Cronne, H. A. & Johnson, Charles. Regesta Regum Anglo-Normannorum 1066–1154. Volume II: Regesta Henriici Primi 1100–1135. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. pp. ix–xlvi. OCLC 634967597.

- Dyer, Christopher (2005). "Bishop Wulfstan and His Estates". In Brooks, Nicholas; Barrow, Julia. St. Wulfstan and His World. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. pp. 137–149. ISBN 0-7546-0802-6.

- Fleming, Robin (2004). Kings & Lords in Conquest England (Reprint ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52694-9.

- Green, Judith A. (1997). The Aristocracy of Norman England. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52465-2.

- Green, Judith A. (1986). The Government of England Under Henry I. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37586-X.

- Green, Judith A. (2006). Henry I: King of England and Duke of Normandy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-74452-2.

- Hollister, C. Warren (April 1973). "The Anglo-Norman Civil War: 1101". The English Historical Review. 88 (347): 315–334. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXXVIII.CCCXLVII.315. JSTOR 564288.

- Hollister, C. Warren (2001). Frost, Amanda Clark, ed. Henry I. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08858-2.

- Hollister, C. W. (1980). "Henry I and the Anglo-Norman Magnates". In Brown, R. Allen. Proceedings of the Battle Conference on Anglo-Norman Studies II. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 93–107. ISBN 0-85115-126-4.

- Holt, Richard (2005). "The City of Worcester in the Time of Wulfstan". In Brooks, Nicholas; Barrow, Julia. St. Wulfstan and His World. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. pp. 123–135. ISBN 0-7546-0802-6.

- Huscroft, Richard (2005). Ruling England 1042–1217. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0-582-84882-2.

- Keats-Rohan, Katharine S. B. (1999). Domesday People: A Prosopography of Persons Occurring in English Documents, 1066–1166: Domesday Book. Ipswich, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-722-X.

- Lewis, C. P. (February 2009). "Companions of the Conqueror (act. 1066–1071)" ((subscription or UK public library membership required)). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online Edition. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- Loyd, Lewis Christopher (1975) [1951]. The Origins of Some Anglo-Norman Families (Reprint ed.). Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8063-0649-1.

- Mason, Emma (2002). "Administration and Government". In Harper-Bill, Christopher; van Houts, Elizabeth. A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell. pp. 135–164. ISBN 978-1-84383-341-3.

- Mason, Emma (1984). "Legends of the Beauchamps' Ancestors: The Use of Baronial Propaganda in Medieval England". Journal of Medieval History. 10: 25–40. doi:10.1016/0304-4181(84)90023-X.

- Mason, Emma (1980). "Magnates, Curiale and the Wheel of Fortune: 1066–1154". In Brown, R. Allen. Proceedings of the Battle Conference on Anglo-Norman Studies II. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 118–140. ISBN 0-85115-126-4.

- Mason, Emma (1996). "St Oswald and St Wulfstan". In Brooks, Nicholas; Cubitt, Catherine. St Oswald of Worcester: Life and Influence. London: Leicester University Press. pp. 269–284. ISBN 0-7185-0003-2.

- Mason, Emma (2005). William II: Rufus, the Red King. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-3528-0.

- Mooers, Stephanie L. (Winter 1982). "Familial Clout and Financial Gain in Henry I's Later Reign". Albion. 14 (3 & 4): 268–291. doi:10.2307/4048517. JSTOR 4048517.

- Newman, Charlotte A. (1988). The Anglo-Norman Nobility in the Reign of Henry I: The Second Generation. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-8138-1.

- Offler, H. S. (July 1951). "The Tractate de Iniusta Vexacione Willelmi Episcopi Primi". The English Historical Review. 66 (260): 321–341. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXVI.CCLX.321. JSTOR 555778.

- Pettifer, Adrian (1995). English Castles: A Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell. ISBN 0-85115-782-3.

- Prestwich, J. O. (January 1981). "The Military Household of the Norman Kings". The English Historical Review. 96 (378): 1–35. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCVI.CCCLXXVIII.1. JSTOR 568383.

- Roffe, David (2007). Decoding Domesday. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-307-9.

- Round, John H. (2004). "Abetot, Urse d' (c.1040–1108)" ((subscription or UK public library membership required)). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Mason, Emma (revised). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 3 February 2009.

- Sanders, I. J. (1960). English Baronies: A Study of Their Origin and Descent 1086–1327. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. OCLC 931660.

- Saul, Nigel (2000). A Companion to Medieval England 1066–1485. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-2969-8.

- Southern, R. W. (1933). "Ranulf Flambard and Early Anglo-Norman Administration". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society: Fourth Series. 16: 95–128. doi:10.2307/3678666. JSTOR 3678666.

- Stafford, Pauline (1989). Unification and Conquest: A Political and Social History of England in the Tenth and Eleventh Centuries. London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 0-7131-6532-4.

- Thomas, Hugh M. (2007). The Norman Conquest: England after William the Conqueror. Critical Issues in History. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-7425-3840-0.

- West, Francis (1966). The Justiciarship in England 1066–1232. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 953249.

- White, Geoffrey H. (1930). "King Stephen's Earldoms". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society: Fourth Series. 13: 51–82. doi:10.2307/3678488. JSTOR 3678488.

- Williams, Ann (2005). "The Cunning of the Dove: Wulfstan and the Politics of Accommodation". In Brooks, Nicholas; Barrow, Julia. St. Wulfstan and His World. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. pp. 23–38. ISBN 0-7546-0802-6.

- Williams, Ann (2000). The English and the Norman Conquest. Ipswich, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 0-85115-708-4.

- Williams, Ann (2003). "An Introduction to the Worcestershire Domesday". In Alecto Historical Editions. The Digital Domesday: Silver Edition. Editions Alecto (Domesday), Ltd. ISBN 1-871118-26-3.

- Wormald, Patrick (1996). "Oswaldslow: An Immunity?". In Brooks, Nicholas; Cubitt, Catherine. St Oswald of Worcester: Life and Influence. London: Leicester University Press. pp. 117–128. ISBN 0-7185-0003-2.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Beauchamp cartulary – catalogue entry from the British Library for the manuscript of the Beauchamp cartulary, which contains some information on Urse