Vinclozolin

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

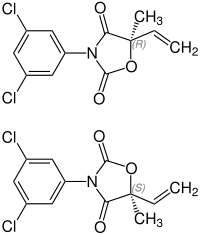

| IUPAC name

(RS)-3-(3,5-Dichlorophenyl)-5-methyl- 5-vinyloxazolidine-2,4-dione | |

| Other names

Vinclozoline | |

| Identifiers | |

| 50471-44-8 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:9986 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL513221 |

| ChemSpider | 36278 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.051.437 |

| KEGG | C10981 |

| PubChem | 39676 |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C12H9Cl2NO3 | |

| Molar mass | 286.11 g·mol−1 |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Vinclozolin (trade names Ronilan, Curalan, Vorlan, Touche) is a common dicarboximide fungicide used to control diseases, such as blights, rots and molds in vineyards, and on fruits and vegetables such as raspberries, lettuce, kiwi, snap beans, and onions. It is also used on turf on golf courses.[1] Two common fungi that vinclozolin is used to protect crops against are Botrytis cinerea and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum.[2] First registered in 1981, vinclozolin is widely used but its overall application has declined. As a pesticide, vinclozolin is regulated by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA). In addition to these restrictions within the United States, as of 2006 the use of this pesticide was banned in several countries, including Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden.[3] It has gone through a series of tests and regulations in order to evaluate the risks and hazards to the environment and animals. Among the research, a main finding is that vinclozolin has been shown to be an endocrine disruptor with antiandrogenic effects.[4]

Use in the United States

Vinclozolin is manufactured by the chemical company BASF and has been registered for use in the United States since 1981. The following is a compilation of data indicating the national use of vinclozolin per crop (lbs AI/yr) in 1987: apricots, 124; cherries, 3,301; green beans, 13,437; lettuce, 24,779; nectarines, 1,449; onions, 829; peaches, 15,203; plums, 163; raspberries, 3,247; and strawberries, 41,006.[5] In 1997, two applications totaling 285 pounds each, were applied to kiwifruit in California to prevent the gray mold and soft rot caused by Botrytis cinerea.[6] In general, the United States has seen an overall decline in the national use of vinclozolin. In 1992, a total of approximately 135,000 pounds were used. However, in 1997 this number dropped to 122,000 and in 2002 it was down to 55,000 pounds.[7]

Preparation and application

The following chemical reactions are used to make vinclozolin:[8] One method combines methyl vinyl ketone, sodium cyanide, 3,5-dichloroaniline, and phosgene. This process involves formation of the cyanohydrin, followed by hydrolysis of the nitrile.[5] Vinclozolin is also prepared by the reaction of 3,5-dichlorophenyl isocyanate with an alkyl ester of 2-hydroxy-2-vinylpropionic acid. Ring closure is achieved at elevated temperature.[5]

Vinclozolin is then formulated into a dry flowable or extruded granular. It can be applied by through the air (aerial), through irrigation systems (chemigation), or by ground equipment. Vinclozolin is also applied to some plants, such as decorative flowers, as a dip treatment where the plant is dipped into the fungicide solution and then dried. It is also common to spray a vinclozolin solution using thermal foggers in greenhouses.[1]

History of regulations in the US

All pesticides sold or distributed in the United States must be registered by U.S. EPA. Pesticides that were first registered before November 1, 1984, were reregistered so that they can be retested using the now more advanced methods. Because vinclozolin was released in 1981, it has gone through both preliminary and a subsequent reregistration.[1] Below is a list of the history of regulations for vinclozolin:

- A Data Call-In (DCI), requiring data on product and residue chemistry, toxicity, environmental fate, and ecological effects, have been requested in 1991, 1995 and 1996.[1]

- Agricultural Data Call-In (AGDCI), to estimate what happens to workers after they apply the fungicide, was issued in 1995.[1]

- In April 1997, BASF proposed a new use for vinclozolin and thus all risks were reevaluated under the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA).[1]

- In June 1998 the EPA put a new safety factor on vinclozolin. BASF voluntarily cancelled vinclozolin use on some fruits and turf.[1]

- On July 18, 2000 the EPA established that certain meat, bean and dairy products have a 3-year time-limited tolerances for vinclozolin and its metabolites. This led to a phase-out of most domestic food uses for vinclozolin. In September 2000, the EPA received objections to the issued tolerance for beans.[1]

- Other measures that BASF has taken to reduce risks: cancel use on decorative plants and set up new restrictions on turf which state that the application to turf restricted to golf courses and industrial sites.[1]

- BASF has proposed to immediately eliminate or phase-out uses such that only use on canola and turf will remain after 2004.[9]

Means of exposure

The U.S. EPA has examined dietary (food and water), non-dietary, and occupational exposure to vinclozolin or its metabolites. In general, fungicides have been shown to circulate through the water and air, and it possible for them to end up on untreated foods after application. Consumers alone cannot easily reduce their exposure because fungicides are not removed from produce that is washed with tap water.[10] A key example of exposure to vinclozolin is through wine grapes which is considered to account for about 2% of total vinclozolin exposure.[11] It has been determined that people may be exposed to residues of vinclozolin and its metabolites containing the 3,5-dichloroaniline moiety (3,5-DCA) through diet, and thus tolerance limits have been established for each crop.[1] Although vinclozolin is not registered for use by homeowners, it is still possible for people to come in to contact with the fungicide and its residues. For example, golfers playing on treated golf courses, and families playing on sod which has been previously treated may be at risk for exposure.[1] Occupationally, workers can be exposed to vinclozolin while doing activities such as loading and mixing.[1]

Environmental and health impacts

Antiandrogen

As part of the reregistration process, the U.S. EPA reviewed all toxicity studies on vinclozolin. The main effect induced by vinclozolin is related to its antiandrogenic activity and its ability to act as a competitive antagonist of the androgen receptor.[4] Vinclozolin can mimic male hormones, like testosterone, and bind to androgen receptors, while not necessarily activating those receptors properly. There is evidence that vinclozolin itself binds weakly to the androgen receptor but that at least two of its metabolites are responsible for much of the antiandrogenic activity.[9] When male rats were given low dose levels (>3 mg/kg/day) of vinclozolin, effects such as decreased prostate weight, weight reduction in sex organs, nipple development, and decreased ano-genital distance were noted. At higher dose levels, male sex organ weight decreased further, and sex organ malformations were seen, such as reduced penis size, the appearance of vaginal pouches and hypospadias.[9] In the rat model, it has been shown that the antiandorgenic effects of vinclozolin are most prominent during the developmental stages.[9] In utero, this sensitive period of fetal development occurs between gestation days 16-17.[12] Embryonic exposure to vinclozolin can influence sexual differentiation, gonadal formation, and reproductive functions.[13] In bird models, vinclozolin and its metabolites were shown in vitro and in vivo to inhibit androgen receptor binding and gene expression. Vinclozolin caused reduced egg laying, reduced fertility rate, and a reduction in successful hatches.[1] Androgens also play a role in puberty, and it has been shown an antiandrogen like vinclozolin can delay pubertal maturation.[12] Antiandrogenic toxins are also known to alter sexual differentiation and reproduction in the rabbit model. Male rabbits exposed to vinclozolin in utero or during infancy did not show a sexual interest in females or did not ejaculate.[12] Since the androgen receptor is widely conserved across species lines, antiandrogenic effects would be expected in humans.[9] In vertebrates, vinclozolin also acts as a neuroendocrine disruptor, affecting behaviors tied to locomotion, cognition, and anxiety.[14]

Progesterone and estrogen effects in rats

In rats, vinclozolin has been shown to affect other steroid hormone receptors, such as those of progesterone and estrogen. Just as with androgens, the timing of the exposure to vinclozolin determines the magnitude of the effects related to these hormones. In a study with rats, in vitro research showed the ability of two vinclozolin metabolites to bind to the progesterone receptor. However, the same study in vivo using adult male rats showed no effects.[15] When mice experienced vinclozolin exposure in utero, male offspring exhibited up-regulated estrogen receptor and up-regulated progesterone receptor. In females, vinclozolin down-regulated expression of estrogen receptors and up-regulated progesterone receptor expression. This result causes virilization and the feminization of males and masculinization of females.[15]

Transgenerational effects

In rats, vinclozolin has been demonstrated to have trangenerational effects, meaning that not only is the initial animal affected, but effects are also seen in subsequent generations. One study demonstrated that vinclozolin impaired male fertility not only in the first generation that was exposed in utero, but in males born for three generations and beyond.[16] Furthermore, when affected males with were mated with normal females, some of the offspring were sterile and some had reduced fertility. After three generations, male offspring continued to show low sperm count, prostate disease and high rates of testicular cell apoptosis.,[16][17] Other studies conducted experiments where rat embryos were exposed to vinclozolin during sex determination. F1 (first generation) vinclozolin treated males were bred with F1 vinclozolin treated females. This pattern continued for three generations. The initial F0 mother was the only subject that was directly exposed to doses of vinclozolin. F1-F4 generation males all showed an increase in the prevalence of tumors, prostate disease, kidney disease, test abnormalities and immune failures when compared to the control group. F1-F4 females also showed an increased incidence of tumors and kidney disease.[13] Furthermore, transgenerationally transmitted changes in mate preference and anxiety behavior have also been observed in rats following exposure to vinclozolin.[18] It has been reported that these transgenerational reports correlate with epigenetic changes, specifically, an alteration in DNA methylation in the male germ line.[18] However, these transgenerational changes have not been successfully reproduced by other laboratories [19]

Links to cancer

The U.S. EPA has classified vinclozolin as a possible human carcinogen. Vinclozolin induces an increase in leydig cell tumors in rats. The 3,5-DCA metabolite is thought to possess a mode of tumor induction based on its similarity to p-choroaniline.[9]

Environment

Laboratory test indicate that vinclozolin easily breaks down and dissipates in the environment with the help of microbes. Of its several metabolites 3,5-dichloroaniline resists further degradation.[9] In terrestrial field dissipation studies conducted in various states, vinclozolin dissipated with a half-life between 34 and 94 days. Half-lives including residues can reach up to 1,000 days. Residues may accumulate and be available for future crop uptake.[9]

Alternative fungicides

Since the phase-out of vinclozolin, farmers are faced with fewer options to control gray and white mold. The New York State Agricultural Experiment Station has carried out efficacy trials for gray and white mold. Research has showed potential alternatives to vinclozolin. Trifloxystrobin (Flint), iprodione (Rovral), and cyprodinil plus fludioxonil (Switch) control gray mold. Thiophanate-methyl (Topsin M) was as effective as vinclozolin in controlling white molds. Switch was the most promising alternative to vinclozolin for controlling both gray and white mold on pods and for increasing marketable yield.[20]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 "R.E.D Facts Vinclozolin" (PDF). EPA. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ↑ "Vinclozolin" (PDF). Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ↑ Boyd, David R. (October 2006). The Food We Eat: An International Comparison of Pesticide Regulations (PDF). Vancouver, BC, Canada: David Suzuki Foundation. p. 12. ISBN 0-9737599-9-2. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- 1 2 Hejmej, Anna; Kotula-Balak, Magorzata; Bilinsk, Barbara (2011). "Antiandrogenic and Estrogenic Compounds: Effect on Development and Function of Male Reproductive System". Steroids - Clinical Aspect. doi:10.5772/28538. ISBN 978-953-307-705-5.

- 1 2 3 Vinclozolin from PubChem

- ↑ "Crop Profile for Kiwi in California" (PDF). UC Davis. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ↑ "Pesticide Use in U.S. Crop Production: 2002 Fungicides and Herbicides" (PDF). Crop Life Foundation. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ↑ Franz Müller, Peter Ackermann and Paul Margot "Fungicides, Agricultural, 2. Individual Fungicides" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.o12_o06

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Reregistration Eligibility Decision: Vinclozolin" (PDF). EPA. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ↑ Colbert, Nathan K.W.; Pelletier, Nicole C.; Cote, Joyce M.; Concannon, John B.; Jurdak, Nicole A.; Minott, Sara B.; Markowski, Vincent P. (2005). "Perinatal Exposure to Low Levels of the Environmental Antiandrogen Vinclozolin Alters Sex-Differentiated Social Play and Sexual Behaviors in the Rat". Environmental Health Perspectives. 113 (6): 700–7. doi:10.1289/ehp.7509. PMC 1257594

. PMID 15929892.

. PMID 15929892. - ↑ Environmental Protection Agency (26 March 2003). "Vinclozolin; Notice of Filing a Pesticide Petition To Establish a Tolerance for a Certain Pesticide Chemical in or on Food". Federal Register: 14628–14635. Retrieved 8 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 Gray, L. E.; Ostby, J; Furr, J; Wolf, C. J.; Lambright, C; Parks, L; Veeramachaneni, D. N.; Wilson, V; Price, M; Hotchkiss, A; Orlando, E; Guillette, L (2001). "Effects of environmental antiandrogens on reproductive development in experimental animals". Human Reproduction Update. 7 (3): 248–64. doi:10.1093/humupd/7.3.248. PMID 11392371.

- 1 2 Anway, Matthew D.; Leathers, Charles; Skinner, Michael K. (2006). "Endocrine Disruptor Vinclozolin Induced Epigenetic Transgenerational Adult-Onset Disease". Endocrinology. 147 (12): 5515. doi:10.1210/en.2006-0640. PMID 16973726.

- ↑ León-Olea, Martha; Martyniuk, Christopher J.; Orlando, Edward F.; Ottinger, Mary Ann; Rosenfeld, Cheryl S.; Wolstenholme, Jennifer T.; Trudeau, Vance L. (1 July 2014). "Current concepts in neuroendocrine disruption". General and Comparative Endocrinology. 203: 158–173. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.02.005. PMC 4133337

. PMID 24530523. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

. PMID 24530523. Retrieved 6 February 2015. - 1 2 Buckley, Jill; Willingham, Emily; Agras, Koray; Baskin, Laurence (2006). "Embryonic exposure to the fungicide vinclozolin causes virilization of females and alteration of progesterone receptor expression in vivo: an experimental study in mice". Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source. 5: 4. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-5-4. PMC 1403752

. PMID 16504050.

. PMID 16504050. - 1 2 Gilbert, Scott; Epel, David (2009). Ecological Developmental Biology [Integrating Epigenetics, Medicine, and Evolution]. MA: Sinauer Associates. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-87893-299-3.

- ↑ Skinner, Michael K.; Anway, Matthew D. (2007). "Epigenetic Transgenerational Actions of Vinclozolin on the Development of Disease and Cancer". Critical Reviews in Oncogenesis. 13 (1): 75–82. doi:10.1615/CritRevOncog.v13.i1.30. PMID 17956218.

- 1 2 Gaetano, Carlo; Guerrero-Bosagna, Carlos; Settles, Matthew; Lucker, Ben; Skinner, Michael K. (2010). "Epigenetic Transgenerational Actions of Vinclozolin on Promoter Regions of the Sperm Epigenome". PLoS ONE. 5 (9): e13100. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0013100. PMC 2948035

. PMID 20927350.

. PMID 20927350. - ↑ Schneider, Steffen; Marxfeld, Heike; Gröters, Sibylle; Buesen, Roland; van Ravenzwaay, Bennard (2013). "Vinclozolin—No transgenerational inheritance of anti-androgenic effects after maternal exposure during organogenesis via the intraperitoneal route". Reproductive Toxicology. 37: 6–14. doi:10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.12.003. PMID 23313085.

- ↑ "Alternatives to Vinclozolin (Ronilan) for Controlling Gray and White Mold on Snap Bean Pods in New York" (PDF). Plant Management Network. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

External links

- BBC article on Vinclozolin in rats

- Vinclozolin in the Pesticide Properties DataBase (PPDB)