Virginia v. West Virginia

| Virginia v. West Virginia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Decided March 6, 1871 | |||||||

| Full case name | State of Virginia v. State of West Virginia | ||||||

| Citations |

20 L. Ed. 67; 11 Wall. 39 | ||||||

| Holding | |||||||

| Where a governor has discretion in the conduct of the election, the legislature is bound by his action and cannot undo the results based on fraud. | |||||||

| Court membership | |||||||

| |||||||

| Case opinions | |||||||

| Majority | Miller, joined by Chase, Nelson, Swayne, Strong, Bradley | ||||||

| Dissent | Davis, joined by Clifford, Field | ||||||

Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39 (1871), is a 6-to-3 ruling by the Supreme Court of the United States which held that where a governor has discretion in the conduct of the election, the legislature is bound by his action and cannot undo the results based on fraud. The Court implicitly affirmed that the breakaway Virginia counties had received the necessary consent of both the State of Virginia and the United States Congress to become a separate state, and explicitly held that the counties of Berkeley and Jefferson were part of the new state of West Virginia.

Background

At the beginning of the American Civil War, Virginia seceded from the United States in 1861.[1] But many of the northwestern counties of Virginia were decidedly pro-union.[2][3] At a convention duly called by the governor and authorized by the legislature, delegates voted on April 17, 1861, to approve Virginia's secession from the United States.[4] Although the resolution required approval from voters (at an election scheduled for May 23, 1861), Virginia's governor entered into a treaty of alliance with the Confederate States of America on April 24, elected delegates to the Confederate Congress on April 29, and formally entered the Confederacy on May 7.[4] For President Lincoln, these actions proved that rebels had taken over the state and turned the machinery of the state toward insurrection. These individuals had not acted with popular support, and thus Lincoln felt justified later in recognizing the Reorganized Government.[5]

Unionist sentiment was so high in the northwestern counties that civil government began to disintegrate, and the Wheeling Intelligencer newspaper called for a convention of delegates to meet in the city of Wheeling to consider secession from the commonwealth of Virginia.[6] Delegates duly assembled, and at the First Wheeling Convention (also known as the May Convention), held May 13 to 15, the delegates voted to hold off on secession from Virginia until Virginia formally seceded from the United States.[7][8] Concerned that the irregular nature of the First Wheeling Convention might not democratically represent the will of the people, elections were scheduled for June 4 to formally elect delegates to a second convention, if necessary.[7][8] Virginians voted to approve secession on May 23. On June 4, elections were held and delegates to a Second Wheeling Convention elected. These elections were irregular as well: Some were held under military pressure, some counties sent no delegates, some delegates never appeared, and voter turnout varied significantly.[9][10] On June 19, the Second Wheeling Convention declared the offices of all government officials who had voted for secession vacant, and reconstituted the executive and legislative branches of the Virginia government from their own ranks.[3][11] The Second Wheeling Convention adjourned on June 25 with the intent of reconvening on August 6.[12]

The new Reorganized Governor, Francis Harrison Pierpont, asked President Abraham Lincoln for military assistance,[12][13] and Lincoln recognized the new government.[12][14] The region elected new U.S. Senators and its two existing Representatives took their old seats in the House, effectively giving Congressional recognition to the Reorganized Government as well.[3][12][15]

After reconvening on August 6, the Second Wheeling Convention again debated secession from Virginia. The delegates adopted a resolution authorizing the secession of 39 counties, with the counties of Berkeley, Greenbrier, Hampshire, Hardy, Jefferson, Morgan, and Pocahontas to be added if their voters approved, and authorizing any contiguous counties with these to join the new state if they so voted as well.[14][16] On October 24, 1861, voters in the 39 counties plus voters in Hampshire and Hardy counties voted to secede from the commonwealth of Virginia. In eleven counties voter participation was less than 20%, with counties like Raleigh and Braxton showing only 5% and 2% voter turnout.[17][18] The ballot also allowed voters to choose delegates to a constitutional convention, which met from November 26, 1861, to February 18, 1862.[19] The convention chose the name "West Virginia," but then engaged in lengthy and acrimonious debate over whether to extend the state's boundaries to other counties which had not voted to secede.[20] Added to the new state were McDowell, Mercer, and Monroe counties.[21] Berkeley, Frederick, Hampshire, Hardy, Jefferson, Morgan, and Pendleton counties were again offered the chance to join, which all but Frederick County did.[21] Eight counties, Greenbrier, Logan, McDowell, Mercer, Monroe, Pocahontas, Webster, and Wyoming, never participated in any of the polls initiated by the Wheeling government, although they were included in the new state.[22] A new constitution for West Virginia was adopted on February 18, 1862, which was approved by voters on April 4.[23]

Governor Pierpont recalled the Reorganized state legislature, which voted on May 13 to approve the secession (and to include Berkeley, Frederick, and Jefferson counties if they approved the new West Virginia constitution as well).[23][24] After much debate over whether Virginia had truly given its consent to the formation of the new state,[25][26] the United States Congress adopted a statehood bill on July 14, 1862, which contained the proviso that all blacks in the new state under the age of 21 on July 4, 1863, be freed.[27][28] President Lincoln was unsure of the bill's constitutionality, but, pressed by Northern senators, he signed the legislation on December 31, 1862.[29][30] Luckily, the West Virginia constitutional convention had not adjourned sine die, and was called back into session on February 12, 1863.[31] The convention amended the state's constitution on February 17 to include the congressionally required slave freedom provision, and adjourned sine die on February 20.[32] The state's voters ratified the slave freedom amendment on March 26, 1863.[32] On April 20, President Lincoln announced that West Virginia would become a state in 60 days.[32]

But Berkeley, Frederick, and Jefferson counties never held votes on secession or the new West Virginia state constitution, as they were under the military control of the Confederacy at the time.[33] On January 31, 1863, the Reorganized legislature of Virginia passed legislation authorizing the Reorganized governor to hold elections in Berkeley County on whether to join West Virginia or not.[34] The Reorganized legislature similarly approved on February 4, 1863, an election for Jefferson County (among others).[35] These elections were held, voters approved secession, and Berkeley and Jefferson Counties were admitted to West Virginia.[36]

However, on December 5, 1865, the Virginia Assembly in Richmond passed legislation repealing all the acts of the Reorganized government regarding secession of the 39 counties and the admission of Berkeley and Jefferson counties to the state of West Virginia.[37]

On March 10, 1866, Congress passed a resolution acknowledging the transfer of the two counties to West Virginia from Virginia.[38]

Virginia sued, arguing that no action had taken place under the act of May 13, 1862, requiring elections, and that the elections which occurred in 1863 were fraudulent and irregular. West Virginia filed a demurrer which alleged that the Supreme Court lacked jurisdiction over the case because it was of a purely political nature.

Decision

Majority holding

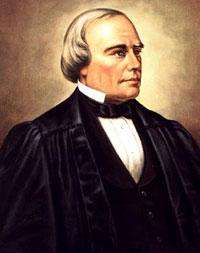

Associate Justice Samuel Freeman Miller wrote the decision for the majority, joined by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase and Associate Justices Samuel Nelson, Noah Haynes Swayne, William Strong, and Joseph P. Bradley.

Justice Miller first disposed of the demurrer. He concluded that the demurrer could not be granted "without reversing the settled course of decision in this court and overturning the principles on which several well-considered cases have been decided."[39] He noted that the court had asserted its jurisdiction in several cases before, including The State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations v. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 37 U.S. 657 (1838); State of Missouri v. State of Iowa, 48 U.S. 660 (1849); Florida v. Georgia, 58 U.S. 478 (1854); and State of Alabama v. State of Georgia, 64 U.S. 505 (1860).[40]

Justice Miller then posed three questions for the Court to answer: :"1. Did the State of Virginia ever give a consent to this proposition which became obligatory on her? 2. Did the Congress give such consent as rendered the agreement valid? 3. If both these are answered affirmatively, it may be necessary to inquire whether the circumstances alleged in this bill, authorized Virginia to withdraw her consent, and justify us in setting aside the contract, and restoring the two counties to that State."[41] Justice Miller then reviewed the various acts taken to reorganize the government of Virginia in 1861, and the various acts which the Reorganized Government and the United States took to create the state of West Virginia and extend its jurisdiction over the counties in question.[42] In answering the first question, Miller wrote, "Now, we have here, on two different occasions, the emphatic legislative proposition of Virginia that these counties might become part of West Virginia; and we have the constitution of West Virginia agreeing to accept them and providing for their place in the new-born State."[43] There was no question, in the mind of the majority, that Virginia had given its consent. Although the elections had been postponed due to a "hostile" environment, the majority concluded that the Reorganized Government of Virginia had acted in "good faith" to carry out its electoral duties in the two counties.[44]

In regard to the second question, Miller pondered the nature of Congressional consent. Congress could not be expected to explicitly give its consent to every single aspect of the proposed state constitution, Miller argued.[45] And clearly Congress had intensively considered the proposed state constitution (which contained provisions for accession of the two counties in question), because Congress seriously considered the slavery question regarding the admission of the new state and required changes in the proposed constitution before statehood could be granted.[46] This debate could only lead the Court to a single conclusion, Miller stated: "It is, therefore, an inference clear and satisfactory that Congress by that statute, intended to consent to the admission of the State with the contingent boundaries provided for in its constitution and in the statute of Virginia, which prayed for its admission on those terms, and that in so doing it necessarily consented to the agreement of those States on that subject. There was then a valid agreement between the two States consented to by Congress, which agreement made the accession of these counties dependent on the result of a popular vote in favor of that proposition."[47]

Miller now considered the third question. The majority held that although the language of the two statutes of January 31, 1863, and February 4, 1863, were different, they had the same legal intent and force.[48] Virginia showed "good faith" in holding the elections, Miller asserted.[48] That the Reorganized Virginia legislature did not require vote totals to be reported to it and delegated the transmission of the vote totals to West Virginia was not at issue, Miller said. It gave the Reorganized Governor discretion as to when and where to hold the votes, under what condition the votes should be held, and to certify the votes. The legislature acted within its power to delegate these duties to the Reorganized Governor, "and his decision [was] conclusive as to the result."[49] Were these votes fair and regular? The Virginia Assembly, Miller noted, made only "indefinite and vague" allegations about vote fraud, and unspecified charges that somehow Governor Pierpont must have been "misled and deceived" by others into believing the voting was fair and regular.[49] Miller pointedly observed that not a single person was charged with fraud, no specific act of fraud was stated, and no legal wrongs asserted.[49] The Virginia Assembly also did not claim that the state of West Virginia interfered in the elections.[49] Absent such allegations, Virginia's accusations cannot be sustained, Miller concluded. But even if this aspect of Virginia's argument was ignored, Miller wrote, the Reorganized legislature had delegated all its power to certify to the election to Governor Pierpont, and he had certified it. That alone laid to rest Virginia's allegations.[50] "[She] must be bound by what she had done. She can have no right, years after all this has been settled, to come into a court of chancery to charge that her own conduct has been a wrong and a fraud; that her own subordinate agents have misled her governor, and that her solemn act transferring these counties shall be set aside, against the will of the State of West Virginia, and without consulting the wishes of the people of those counties."[51]

Dissent

Associate Justice David Davis wrote a dissent, joined by Associate Justices Nathan Clifford and Stephen Johnson Field.

Davis concluded that Congress never gave its consent to the transfer of Berkeley and Jefferson counties to West Virginia.[51] By the time Congress did so (on March 10, 1866), the legislature of Virginia had already withdrawn its consent to the transfer of the two counties.[51]

Davis disagreed with the majority's view that Congress had consented to the transfer of the two counties when it debated the proposed West Virginia constitution. There was nothing in the debates to ever suggest that, he wrote.[52] What Congress agreed to was that the two counties should be offered the chance to join West Virginia by the time of the new state's admission to union with the United States.[52] These conditions had not been met by the time of admission, and thus no transfer could be constitutionally made.[52] Congress had not agreed to additional legislative acts of transfer, and thus they could not be made without Virginia's assent (which was now withdrawn).[52]

Assessment

When Virginia v. West Virginia first came to the Supreme Court in 1867, there were only eight Justices on the bench due to the death of Justice James Moore Wayne on July 5, 1867. The Court would not have nine Justices again until the resignation of Justice Robert Cooper Grier on January 31, 1870, and the confirmation of Justices William Strong (February) and Joseph P. Bradley (March) in 1870. During this three-year period, the Supreme Court was divided 4-to-4 as to whether it had jurisdiction over the case.[53][54] Chief Justice Chase delayed taking up the case until a majority emerged in favor of affirming the Court's original jurisdiction rather than seek a ruling on the issue.[53] The acceptance of original jurisdiction in this matter is now considered one of the most significant jurisdictional cases in the Court's history.[55]

It is noteworthy that former Associate Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis argued the case on behalf of Virginia before the Court.[55] He lost. Curtis, as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, had dissented from the holding in Dred Scott v. Sandford.

Many in Congress questioned both the legality of the Reorganized Virginia government and the constitutionality of the creation of West Virginia.[25][26] Many scholars since have questioned the democratic nature of the Second Wheeling Convention, the legal and moral legitimacy of the Reorganized Government, and the constitutionality of the creation of West Virginia.[56] But most lengthy scholarly treatments of the issue assert the legality of the Reorganized government. In Luther v. Borden, 48 U.S. 1 (1849), the Supreme Court held that only the federal government could determine what constituted a "republican form of government" in a state (as provided for in the Guarantee Clause of Article Four of the United States Constitution).[57] Virginia was not alone in having two governments—one unionist, one rebel—with the union government recognized by the United States.[58] The Supreme Court had held in Luther v. Borden, "Under this article of the Constitution it rests with Congress to decide what government is the established one in a State."[59] As both the President and Congress had recognized the Reorganized Government, this provision was met and the entire process was legal.[14][60] There were precedents for such action as well. As one legal scholar has noted, Michigan was admitted to the union after irregular elections for three unauthorized constitutional conventions led to a request for statehood that Congress (eventually) granted in 1837.[61] Kansas, too, went through a highly irregular statehood process marked by violence, mass meetings masquerading as legislative assemblies, and allegations of vote fraud, but it was also admitted to the union.[61] One widely cited legal analysis concludes that "the process of West Virginia statehood was hyper-legal".[62] Indeed, to deny the legality of the Reorganized Government creates significant problems, two legal scholars have argued: "[It] follows, we submit, that 'Virginia' validly consented to the creation of West Virginia with its borders. Indeed, one can deny this conclusion only if one denies one of Lincoln's twin premises: the unlawfulness of secession; or the power of the national government, under the Guarantee Clause, to recognize alternative State governments created by loyal citizens in resistance to insurrectionary regimes that have taken over the usual governing machinery of their States."[63]

Although the U.S. Supreme Court never ruled on the constitutionality of the state's creation, decisions such as those in Virginia v. West Virginia led to a de facto recognition of the state which is now considered unassailable.[32][64][65] West Virginia's first constitution explicitly agreed to pay a portion of Virginia's debt in helping build roads, canals, railroads, and other public improvements in the new state. But these debts were never paid, and Virginia sued to recover them. In the case, Virginia v. West Virginia, 220 U.S. 1 (1911), the state of Virginia admitted in its briefings the legality of the secession of West Virginia.[66][67] A second constitutional question arises as to whether the Constitution permits states to be carved out of existing states, whether consent is given or not. Article IV, Section 3, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution says:

States may be admitted by the Congress into this Union; but no new State shall be formed or erected within the Jurisdiction of any other State; nor any State be formed by the Junction of two or more States, or Parts of States, without the Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned as well as of the Congress.[68]

Should the phrase between the first and second semicolons be read as absolutely barring the creation of a state within the jurisdiction of an existing state, or should it be read in conjunction with the following clause (which permits such creation with the consent of the existing state)? If the former interpretation is adopted, then not only West Virginia but the states of Kentucky, Maine, and possibly Vermont were also created unconstitutionally.[69]

Virginia v. West Virginia was also one of the first cases to establish the principle that Congress may give implied consent, and that such consent may be inferred from the context in which action was taken. It was not the first time the Court had so ruled (it had done so in Poole v. Fleeger, 36 U.S. 185, (1837) and Green v. Biddle, 21 U.S. 1 (1823)).[70] But the statement in Virginia v. West Virginia is the one most cited by the court in its subsequent rulings in Virginia v. Tennessee, 148 U.S. 503 (1893); Wharton v. Wise, 153 U.S. 155 (1894); Arizona v. California, 292 U.S. 341 (1934); James v. Dravo Contracting Co., 302 U.S. 134 (1937); and De Veau v. Braisted, 363 U.S. 144 (1960).[71]

References

- ↑ As one historian has noted: "[Southern soldiers] entered military service to defend rights that the Constitution bequeathed to them, the very same basis upon which their home states of Virginia and Alabama seceded from the Union: They acted to protect the institution of slavery. The Army of Northern Virginia fought for many reasons, but the events that led to its formation clarified the key factor of the Civil War: It was fought over slavery." Glatthaar, 2009, p. 10. James M. McPherson agrees: "The claim that [Lincoln's] call for troops was the cause of the upper South's decision to secede is misleading. ... Scores of [pro-secession] demonstrations took place from April 12 to 14, before Lincoln issued his call for troops. Many conditional unionists were swept along by this powerful tide of southern nationalism; others were cowed into silence." McPherson, 1988, p. 278. (emphasis in original) See also Freehling, 2007, p. 511-513, 526 (discussing pro-secession majority in the Virginia secession convention prior to U.S. President Abraham Lincoln's call for troops).

- ↑ Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 112.

- 1 2 3 McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, 1988, p. 298.

- 1 2 Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 116.

- ↑ Kesavan & Paulsen 2002, pp. 311–312.

- ↑ Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 117-118.

- 1 2 Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 118-120.

- 1 2 Randall, Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln, 1951, p. 438-439.

- ↑ Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 121.

- ↑ Randall, Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln, 1951, p. 441.

- ↑ Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 121-122; Randall, Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln, 1951, p. 443-444.

- 1 2 3 4 Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 122.

- ↑ Kesavan & Paulsen 2002, p. 312.

- 1 2 3 Kesavan & Paulsen 2002, p. 300.

- ↑ Randall, Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln, 1951, p. 453.

- ↑ Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 123.

- ↑ Curry, Richard O., A House Divided, Statehood Politics & The Copperhead Movement in West Virginia, Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, 1964, pgs. 149-151

- ↑ Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 140; McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, 1988, p. 298-299; Randall, Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln, 1951, p. 451-452.

- ↑ Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 140-141.

- ↑ Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 141-143.

- 1 2 Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 143.

- ↑ Curry, Richard O., A House Divided, Statehood Politics & The Copperhead Movement in West Virginia, Univ. of Pittsburgh Press, 1964, pgs. 149-151

- 1 2 Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 146.

- ↑ Randall, Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln, 1951, p. 452.

- 1 2 Davis and Robertson, Virginia at War, Kentucky, 2005, p. 151.

- 1 2 Kesavan & Paulsen 2002, pp. 314–319.

- ↑ Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 147; McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, 1988, p. 303-304; Randall, Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln, 1951, p. 460-461

- ↑ Kesavan & Paulsen 2002, p. 319.

- ↑ Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 149-150

- ↑ Kesavan & Paulsen 2002, pp. 319–325.

- ↑ Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 112, 150.

- 1 2 3 4 Rice and Brown, West Virginia: A History, 1993, p. 151.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 42.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 44-45.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 46.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 47-48.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 48.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 49.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 53.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 54-55.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 56.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 56-58.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 58-59.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 59.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 59-60.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 60.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 60-61.

- 1 2 Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 61.

- 1 2 3 4 Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 62.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 62-63.

- 1 2 3 Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 63.

- 1 2 3 4 Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39, 64.

- 1 2 Fairman, Reconstruction and Reunion, 1864-88, 1987, p. 625; Egger, "Court of Appeals Review of Agency Action: The Problem of En Banc Ties," Yale Law Journal, November 1990, p. 475.

- ↑ Reynolds L. and Young, "Equal Divisions in the Supreme Court: History, Problems, and Proposals," North Carolina Law Review, October 1983, p. 44.

- 1 2 Fenn, "Supreme Court Justices: Arguing Before the Court After Resigning from the Bench," Georgetown Law Journal, July 1996, p. 2478.

- ↑ McGregor, The Disruption of Virginia, 1922, p. 206-223; Randall, Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln, 1951, p. 437-444, 453; Cohen, The Civil War in West Virginia: A Pictorial History, 1996, p. 7; Hoar, Constitutional Conventions: Their Nature, Powers, and Limitations, 1987, p. 22-24; Ebenroth and Kemner, "The Enduring Political Nature of Questions of State Succession and Secession and the Quest for Objective Standards," University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Economic Law, Fall 1996, p. 786; Donald, Lincoln, 1996, p. 300-301.

- ↑ Kesavan & Paulsen 2002, p. 310.

- ↑ McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, 1988, p. 291-297.

- ↑ Luther v. Borden, 48 U.S. 1, 42.

- ↑ Lesser, Rebels at the Gate: Lee and McClellan on the Front Line of a Nation Divided, 2004, p. 78.

- 1 2 Jameson, The Constitutional Convention: Its History, Powers, and Modes of Proceeding, 1867, p. 186-207.

- ↑ Kesavan & Paulsen 2002, p. 302.

- ↑ Kesavan & Paulsen 2002, pp. 312–313.

- ↑ Barnes, "Towards Equal Footing: Responding to the Perceived Constitutional, Legal and Practical Impediments to Statehood for the District of Columbia," University of the District of Columbia Law Review, Spring 2010, p. 18 n.138

- ↑ Kesavan & Paulsen 2002, p. 395.

- ↑ Virginia v. West Virginia, 220 U.S. 1, 24-25.

- ↑ Ebenroth and Kemner, "The Enduring Political Nature of Questions of State Succession and Secession and the Quest for Objective Standards," University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Economic Law, Fall 1996, p. 786-787.

- ↑ U.S. Constitution, Art. IV, Sec. 3, cl. 1.

- ↑ Kesavan & Paulsen 2002, p. 332.

- ↑ Greve, "Compacts, Cartels, and Congressional Consent," Missouri Law Review, Spring 2003, p. 287, n.6.

- ↑ Kogan, "Symposium: The Extra-WTO Precautionary Principle: One European 'Fashion' Export the United States Can Do Without," Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review, Spring 2008, p. 525; "Note: To Form a More Perfect Union?: Federalism and Informal Interstate Cooperation," Harvard Law Review, February 1989, p. 844.

Bibliography

- Barnes, Johnny. "Towards Equal Footing: Responding to the Perceived Constitutional, Legal and Practical Impediments to Statehood for the District of Columbia." University of the District of Columbia Law Review. 13:1 (Spring 2010).

- Cohen, Stan. The Civil War in West Virginia: A Pictorial History. Charleston, W. Va.: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., 1996.

- Curry, Richard O. A House Divided, Statehood Politics & the Copperhead Movement in West Virginia, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1964.

- Davis, William C. and Robertson, James I. Virginia at War. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky, 2005.

- Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln. Paperback ed. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.

- Ebenroth, Carsten Thomas and Kemner, Matthew James. "The Enduring Political Nature of Questions of State Succession and Secession and the Quest for Objective Standards." University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Economic Law. 17:753 (Fall 1996).

- Egger, Daniel. "Court of Appeals Review of Agency Action: The Problem of En Banc Ties." Yale Law Journal. 100:471 (November 1990).

- Fairman, Charles. Reconstruction and Reunion, 1864-88. 2d ed. New York: MacMillan, 1987.

- Fenn, Charles T. "Supreme Court Justices: Arguing Before the Court After Resigning from the Bench." Georgetown Law Journal. 84:2473 (July 1996).

- Freehling, William W. The Road to Disunion: Secessionists Triumphant, 1854-1861. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Glatthaar, Joseph T. General Lee's Army: From Victory to Collapse. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2009.

- Greve, Michael S. "Compacts, Cartels, and Congressional Consent." Missouri Law Review. 68:285 (Spring 2003).

- Hoar, Roger Sherman. Constitutional Conventions: Their Nature, Powers, and Limitations. Littleton, Colo.: F.B. Rothman, 1987.

- Jameson, John Alexander. The Constitutional Convention: Its History, Powers, and Modes of Proceeding. New York: C. Scribner and Co., 1867.

- Kesavan, Vasan; Paulsen, Michael Stokes (2002). "Is West Virginia Unconstitutional?". California Law Review. 90 (2): 291–400.

- Kogan, Lawrence A. "Symposium: The Extra-WTO Precautionary Principle: One European "Fashion" Export the United States Can Do Without." Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review. 17:491 (Spring 2008).

- Lesser, W. Hunter. Rebels at the Gate: Lee and McClellan on the Front Line of a Nation Divided. Naperville, Ill.: Sourcebooks, 2004.

- McGregor, James C. The Disruption of Virginia. New York: MacMillan Co., 1922.

- McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

- "Note: To Form a More Perfect Union?: Federalism and Informal Interstate Cooperation." Harvard Law Review. 102:842 (February 1989).

- Randall, James G. Constitutional Problems Under Lincoln. Rev. ed. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1951.

- Reynolds, William L. and Young, Gordon G. "Equal Divisions in the Supreme Court: History, Problems, and Proposals." North Carolina Law Review. 62:29 (October 1983).

- Rice, Otis K. and Brown, Stephen Wayne. West Virginia: A History. Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky, 1993.