Volodymyr Antonovych

| Volodymyr Antonovych Володимир Боніфатійович Антонович Włodzimierz Antonowicz | |

|---|---|

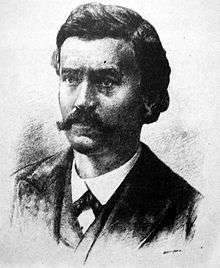

T. Meyerhoffer. Portrait of V. Antonovych, late 19th century. | |

| Born |

January 30, 1834 Makhnovka, Berdichev uyezd, Kiev Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died |

March 21, 1908 (aged 74) Kiev, Russian Empire |

| Resting place | Baikove Cemetery, Kiev |

| Occupation | archeologist, paleographer, historian, ethnographer, and civil activist |

| Language | Russian, Ukrainian, Polish |

| Nationality | Ukrainian |

| Alma mater | Kiev University |

| Notable works | Archives of South-Western Russia (8 volumes) |

| Spouse | Kateryna Melnyk-Antonovych |

| Children | Dmytro Antonovych |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

Volodymyr Antonovych (Ukrainian: Володи́мир Боніфа́тійович Антоно́вич; Polish: Włodzimierz Antonowicz; Влади́мир Бонифа́тьевич Антоно́вич; January 30, 1834, – March 21, 1908, Kiev) was a prominent Ukrainian historian and one of the leaders of the Ukrainian national awakening in the Russian Empire. As a historian, Antonovych, who was longtime Professor of History at the University of Kiev, represented a populist approach to Ukrainian history.

This approach, which earlier had been exemplified by another historian, Mykola Kostomarov (Nikolay Kostomarov), took the side of the common people in the recurrent conflicts between the state and the people which had characterized Ukrainian history over the centuries. Kostomarov, Antonovych, and other populist historians thought the spirit of the nation was embedded in the Ukrainian folk, and saw the various states which had ruled Ukraine as exterior and foreign to this folk.

Nevertheless, he was considered one of the most prominent specialists on pre-history of western Russia.[1]

Biography

He was born January 18, 1834 in the village of Makhnivka (Makhnovka), Vinnytsia Oblast, then in the Imperial Russian Kiev Guberniya. His parents were two local teachers of Polish humble gentry ancestry, though Antonovych later claimed the direct predecessor of his family was a member of the mighty Lubomirski family.[2] He himself on various occasions claimed his father was either Bolesław Antonowicz or a Hungarian wanderer named János Diday.[3] He grew up in his mother's house in Makhnivka, and in early youth moved to Odessa. Little is known of this period in his life.[4]

In 1830 he graduated from the II School for Boys in Odessa and joined the Kiev University.[5][6] Initially he studied medicine, but following the death of his mother he moved to the faculty of history and philology. During his studies he joined the circles of Polish democratically-minded students and took part in the preparations for what became the January Uprising under the auspice of the London-based Polish Democratic Society.[7]

In 1857 he co-founded[8] the Związek Trojnicki ("Triple Society", named after three parts of Poland taken by Russia in 18th century: Volhynia, Podolia and the Kiev area). The society was aimed at promoting the liquidation of serfdom and winning the peasants for the case of Polish independence. At the same time it prepared the members for their role in the planned all-national uprising.[9] As such, Antonowicz became one of the prominent examples of the "peasant-lovers" (Polish: chłopomani, Ukrainian: khlopomany), a loose group of young artists and political thinkers fascinated with the peasantry as the "core of the nation" and stressing the need to win the peasants for the cause.

However, when the January Uprising finally started, the society divided.[10] Antonowicz, highly critical of the szlachta, decided to "go with the people", and left its ranks, instead forming a "Ruthenian" (Ukrainian) society called Kiev Hromada.[11][12] The conflict between Antonowicz and his university colleagues was further aggravated by the conflict over the Polish language. While most democratic societies decided to appeal to the tsar and ask for the Polish language to be promoted to the status of the language of instruction, Antonowicz ultimately opposed those plans.[4][13] This conflict further strengthened Antonowicz's pro-Ukrainian stance on one side, and the animosity between him and his colleagues on the other, to the extent he was considered a "renegade" by some.[14] About that time he also changed his name to its Ruthenized form and converted to Orthodox faith, common among the peasants living around Kiev, as opposed to Catholicism confessed by the higher strata of local society.[4]

By 1863 the Hromada solidified into a small, yet influential student society. It differed from other patriotic societies at the Kiev University in that it stressed the need of Ukrainian national revival as a separate process, while other similar groups saw it as a part of a wider process, in which the basic aim was the restoration of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The Hromada started cautious Ukrainian cultural and educational work under the autocratic Russian Imperial regime. Antonovych, now a prominent member of the Ukrainian national movement, criticized the largely Polonized nobility and gentry of right-bank Ukraine for what he saw as betrayal of the true national cause and exploiting the peasantry. Antonovych, who himself was of Polish-speaking nobility from the right-bank, and had probably been influenced by boyhood reading of the pro-Cossack novels of the Polish emigre from right-bank Ukraine, Michał Czajkowski, clearly went over to the Ukrainians at this time.

In the meantime, Antonovych graduated from the university (in 1860) and started his career as a teacher. Initially he taught Latin at the 1st Kiev Gymnasium, but the following year he started teaching History of Russia in the Kiev cadet corps.

Throughout his career, the imperial censors and oppressive political atmosphere prevented Antonovych from openly expressing his political views which tended to be egalitarian and somewhat anarchistic. In addition to being a populist, he was a pioneer of positivist methodology in history, the founder of the so-called "Kiev Documentalist School" of Ukrainian historians, and mentor of the most famous of these, Mykhailo Hrushevsky.

In 1897 together with the Ukrainian nobleman Oleksandr Konysky organized the All-Ukrainian Public Organization.

Family

Volodymyr Antonovych is the father of the former Ukrainian minister Dmytro Antonovych and the grandfather of Maryna Rudnytska, the Canadian professor in the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Maryna Rudnytska was the wife of Jaroslav Rudnyckyj.

His wife was Kateryna Mykolaivna Antonovych-Melnyk (Dec. 2, 1859 – Jan. 12, 1942) who was a Ukrainian historian and archeologist from the city of Khorol (today – Poltava Oblast). In 1880s she participated in the archeological excavations near Shumsk (today – Ternopil Oblast) and in 1885 visited Ternopil during her travel around the region. Since 1919 Kateryna worked in the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

Notes and references

- In-line:

- ↑ Andrzej Chodubski (February 1994). "Mitrofan Downar-Zapolski (1867-1934) — wybitny badacz historii i kultury Białorusi" (pdf). Беларускі Гістарычны Зборнік - Białoruskie Zeszyty Historyczne (in Polish). 2 (2): 117.

- ↑ Franciszek Gawroński (1912). Włodzimierz Antonowicz : zarys jego działalności społeczno-politycznej i historycznej (in Polish). Lwów: Gebethner i Ska. pp. 11–12.

- ↑ One of Antonovych's letters supports the earlier version, while his memoirs support the latter. See: Gawroński, op.cit., pp. 14-18

- 1 2 3 Gawroński, op.cit., p.22

- ↑ Gawroński, op.cit., p.23

- ↑ Born and raised as a Catholic, during his studies at the Kiev University he converted to the Orthodox faith; see: Gawroński, p.22,

- ↑ Gawroński, op.cit., pp.54-56

- ↑ Together with Leon Głowacki, Włodzimierz Milowicz, Władysław Henszel, Stefan Bobrowski and others

- ↑ Jan Tabiś (1974). Polacy na Uniwersytecie Kijowskim, 1834-1863 (in Polish). Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Literackie. pp. 90–121.

- ↑ Paweł Jasienica (1992). Dwie drogi: o powstaniu styczniowym (in Polish). Warsaw: Czytelnik. pp. 124, 172–177. ISBN 8307022991.

- ↑ Initially Antonowicz's Hromada was composed mostly of Poles, much like other student societies named after various regions of former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, as there were barely any Ukrainians at the university at the time; see for instance Jan Tabiś, op.cit.

- ↑ Andrzej Walicki (January 2003). "Ideologia narodowa powstania styczniowego (2)". Przegląd (in Polish) (4/2003).

- ↑ Franciszek Rawita-Gawroński (1902). "Włodzimierz Antonowicz". Rok 1863 na Rusi (in Polish). Lwów: H. Altenberg. pp. 143–153.

- ↑ Franciszek Rawita-Gawroński, op.cit., p.142