Wasif al-Turki

Wasif al-Turki (Arabic: وصيف التركي) (died October 29, 867) was a Turkish general in the service of the Abbasid Caliphate. He played a central role in the events that followed the assassination of al-Mutawakkil in 861, known as the Anarchy at Samarra. During this period he and his ally Bugha al-Sharabi were often in effective control of affairs in the capital,[1] and were responsible for the downfall of several caliphs and rival officials. After Wasif was killed in 867, his position was inherited by his son Salih.

Early life

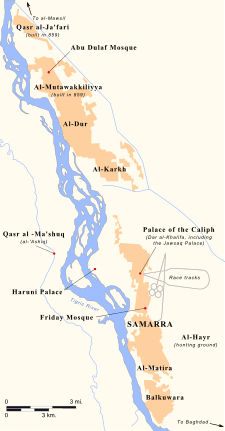

Wasif was originally a slave (ghulam) and was owned by the Nu'man family in Baghdad, where he worked as an armorer. At some point he was purchased by the future caliph al-Mu'tasim (r. 833–842), and he soon rose to prominence as a member of the Abbasids' new Turkish corps.[2] When al-Mu'tasim decided to move his capital to Samarra in 836, Wasif and his followers were settled in the new city, having received land allotments adjacent to al-Hayr.[3] In 838 Wasif participated in al-Mu'tasim's Amorium campaign, and is mentioned as commanding the caliph's advance guard as they passed through the Gates of Tarsus.[4] According to al-Ya'qubi, Wasif also served as al-Mu'tasim's chamberlain (hajib).[5]

During the caliphate of al-Wathiq (r. 842–847), Wasif was granted the Samarran cantonment of al-Matira, which had formerly been in the possession of the disgraced general al-Afshin.[6] In 846 he undertook an expedition to the areas of Isfahan, al-Jibal and Fars, where he attempted to stop a band of Kurds from infiltrating the region.[7]

After al-Wathiq died in 847, Wasif and other high-ranking officers and court officials met to choose his successor. The group eventually agreed to select al-Mutawakkil, and Wasif was among the first to render the oath of allegiance to the new caliph.[8] During al-Mutawakkil's reign (847–861), Wasif was appointed as chamberlain.[9] The caliph also entrusted Wasif's sister Su'ad with the guardianship of his son al-Mu'ayyad.[10]

Assassination of al-Mutawakkil, caliphate of al-Muntasir

Al-Mutawakkil was assassinated by members of his Turkish bodyguard in December 861. Wasif was not a member of the assassination team, but he was a central figure in the plot. Al-Tabari claims that the conspiracy was hatched after al-Mutawakkil ordered Wasif's estates in Isfahan and al-Jibal to be seized in favour of al-Fath ibn Khaqan, and that the caliph had been plotting to kill Wasif and Bugha al-Sharabi, forcing the conspirators to strike against him first. For his part, Wasif was aware of the plan and sent five of his sons, including Salih ibn Wasif, to assist the assassins.[11]

Al-Mutawakkil's death resulted in his eldest son al-Muntasir becoming caliph. During his short reign (861–862), Wasif and Bugha urged the caliph to cancel his father's succession arrangements and depose al-Muntasir's brothers al-Mu'tazz and al-Mu'ayyad from their position as his heirs. The Turks feared that if al-Mu'tazz became caliph, he would seek revenge for al-Mutawakkil's death and eliminate them. They eventually convinced al-Muntasir to force his brothers to abdicate, and instead declare his own son as his successor.[12]

In early 862 Wasif was appointed by the caliph to undertake a major campaign on the Byzantine frontier. The decision to select Wasif was allegedly the work of the vizier Ahmad ibn al-Khasib, a political rival who sought to remove the general from Samarra. Wasif seems to have had no objection to the assignment and led a large force to the frontier, where he captured a fortress from the Byzantines.[13]

Disorder in Samarra, outbreak of civil war

While on campaign at the frontier, Wasif learned of the death of al-Muntasir in June 862, and that a cabal of Turkish officers, including Bugha, had selected al-Musta'in (r. 862–866) to succeed him. Being unable to play any role in the selection process, Wasif decided to continue with the expedition for a time, but by the next year he had returned to Samarra.[14]

During the first year of al-Musta'in's reign, the administration was dominated by his vizier Utamish. When the latter attempted to exclude Wasif and Bugha from power, however, the two officers retaliated by inciting the army against him. This strategy eventually succeeded and Utamish was killed by the mawlas in June 863. Following his death, Wasif and Bugha each received new powers; Wasif was made governor of al-Ahwaz and Bugha was appointed over Palestine.[15] Wasif subsequently also became al-Musta'in's administrative assistant, while his secretary became vizier.[16]

In early 865, Wasif and Bugha ordered the killing of Baghir al-Turki, an officer who had been plotting against them. Baghir, however, was popular with the Turkish soldiers, and a riot broke out when news of his fate became known. Seeing that they were unable to regain control, Wasif, Bugha and al-Musta'in departed from Samarra and made their way to Baghdad, where they were welcomed by its governor Muhammad ibn 'Abdallah ibn Tahir. The Turkish soldiers, seeing that the caliph had abandoned them, decided to depose al-Musta'in and swear allegiance to al-Mu'tazz instead, and an army was dispatched to attack Baghdad.[17]

Over the course of the next year, central Iraq was the site of fighting between the Samarran Turks and forces loyal to al-Musta'in. Wasif and Bugha stayed by the caliph and participated in battles to defend Baghdad, although overall command of al-Musta'in's war effort was in the hands of Muhammad ibn 'Abdallah.[18] By the end of 865, however, hopes for an al-Musta'in victory had diminished, and Wasif, Bugha and Muhammad decided to force the caliph to surrender and abdicate, which he did in January 866. They also negotiated with al-Mu'tazz's forces to bring an end to the war. As part of the agreement, Wasif and Bugha were promised new positions; Wasif was to be appointed over al-Jibal and Bugha was to become governor of the Hijaz.[19]

Under al-Mu'tazz

Following the victory of al-Mu'tazz, Wasif and Bugha initially remained in Baghdad. The new caliph, however, initially took a hostile attitude toward the two officers, and ordered Muhammad to drop their names, together with those they had registered, from the diwans. When Wasif and Bugha discovered in April 866 that one of Muhammad's deputies had been contracted to kill them, they went on the defensive, gathering their troops, purchasing weapons and distributing funds in their neighborhoods.

Wasif and Bugha then called on their allies to pressure al-Mu'tazz to restore them to favor. Wasif bribed al-Mu'ayyad to speak positively to the caliph about him, while Abu Ahmad ibn al-Mutawakkil spoke on Bugha's behalf. The Turkish soldiers also favored allowing them to return to Samarra. In October 866 they received an invitation from the caliph to come to the capital, and they accordingly set out for the city. In the following month, al-Mu'tazz restored them to the positions that they had held prior to their departure to Baghdad.[20]

After their return to Samarra, Wasif and Bugha resumed their administrative duties. Wasif ordered the repair of the Mecca Road and put Abu al-Saj Dewdad in charge of the project. He also appointed the Dulafid 'Abd al-'Aziz ibn Abu Dulaf as his deputy governor in al-Jibal, and sent him cloaks signifying his appointment.[21]

Death

On October 29, 867, the Turkish soldiers, together with the Ushrusaniyya and Faraghina regiments, rioted, demanding four months of their allotments. Bugha, Wasif and Sima al-Sharabi went out with a hundred of their followers and attempted to defuse the situation. Wasif told the rioters that there was no money to pay them, at which point Bugha and Sima decided to depart. The rioters then attacked Wasif, slashing and stabbing him. He was then taken to a nearby residence, but the soldiers dragged him out and struck him with axes until they broke both his arms and decapitated him, and his head was placed on top of a stick.[22]

Following Wasif's death, al-Mu'tazz entrusted Bugha with Wasif's duties.[23] Wasif's son Salih also became an influential figure in Samarra until he was killed in 870.[24]

Notes

- ↑ Sourdel 1960, p. 1351

- ↑ Al-Ya'qubi 1892, p. 256; Gordon 2001, pp. 17, 23, 33, 60

- ↑ Al-Ya'qubi 1892, p. 258

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 33: p. 99

- ↑ Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 584

- ↑ Al-Ya'qubi 1892, p. 264-65; Gordon 2001, p. 86

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 34: pp. 37-38; Gordon 2001, p. 107

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 34: pp. 61-64; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 591; Gordon 2001, p. 80

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 34: p. 82; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 602; Gordon 2001, p. 84

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 35: p. 123; Gordon 2001, p. 107

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 34: pp. 171-180; Gordon 2001, pp. 89-90

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 34: pp. 210 ff.

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 34: pp. 204-09; v. 35: pp. 7-8; Al-Mas'udi 1873, p. 300; Gordon 2001, pp. 91, 130-31

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 35: pp. 7-8, 11

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 35: pp. 12-13; Gordon 2001, p. 95

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 35: p. 25; Sourdel 1959, pp. 293-94

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 35: pp. 28 ff.; Al-Mas'udi 1873, pp. 324-25; 363-65; Gordon 2001, pp. 95-96

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 35: pp. 34, 45, 46, 62, 67, 78, 92, 95-96; Sourdel 1959, p. 294; Gordon 2001, pp. 96-97, sees the war as a "humbling experience" for Wasif and Bugha; cut off from their sources of power in Samarra, they were relegated to becoming virtual onlookers for the duration of the conflict

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 35: pp. 96 ff., 105-08; Gordon 2001, p. 97

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 35: pp. 122-24; Al-Mas'udi 1873, p. 394; Gordon 2001, p. 97

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 35: pp. 143-44

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 35: p. 146; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, p. 614 (who adds that the rioters were from the neighborhood of al-Karkh); Al-Mas'udi 1873, pp. 384 (where the date of death is listed as November 3, 867), 396; Gordon 2001, p. 97

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 35: p. 146

- ↑ Al-Tabari 1985–2007, v. 35: pp. 152, 154, 161-63; v. 36: pp. 7-8, 10-11, 26-27, 68 ff.; Al-Ya'qubi 1883, pp. 614-17; Gordon 2001, pp. 97-98

References

- Gordon, Matthew S. (2001). The Breaking of a Thousand Swords: A History of the Turkish Military of Samarra (A.H. 200-275/815-889 C.E.). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-4795-2.

- Al-Mas'udi, Ali ibn al-Husain (1873). Les Prairies D'Or, Tome Septieme. Ed. and Trans. Charles Barbier de Meynard and Abel Pavet de Courteille. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.

- Sourdel, D. (1960). "Bugha al-Sharabi". The Encyclopedia of Islam, Volume I (New ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-08114-3.

- Sourdel, Dominique (1959). Le Vizirat Abbaside de 749 à 936 (132 à 224 de l'Hégire) Vol. I. Damascus: Institut Français de Damas.

- Al-Tabari, Abu Ja'far Muhammad ibn Jarir (1985–2007). Ehsan Yar-Shater, ed. The History of Al-Ṭabarī. 40 vols. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Al-Ya'qubi, Ahmad ibn Abu Ya'qub (1883). Houtsma, M. Th., ed. Historiae, Vol. 2. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Al-Ya'qubi, Ahmad ibn Abu Ya'qub (1892). de Goeje, M. J., ed. Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum, Pars Septima: Kitab al-A'lak an-Nafisa VII, Auctore Abu Ali Ahmad ibn Omar Ibn Rosteh, et Kitab al-Boldan, Auctore Ahmad ibn Abi Jakub ibn Wadhih al-Katib al-Jakubi. Leiden: E. J. Brill.