William Jackson (Boston loyalist)

| William Jackson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

1731 Cornhill, Boston |

| Died |

1810 England |

| Occupation | Importer at a Boston general store, the Brazen Head |

| Parent(s) |

|

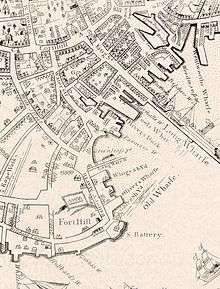

William Jackson (1731-1810)[1] was a Revolutionary era loyalist born in Boston. He inherited and then owned a general store called “The Brazen Head.” The store was located in Cornhill, an area in the center of Boston.[2] Because of his loyalty to the crown, Jackson made enemies with many patriotic Bostonians, and was the target of frequent intimidation by the Sons of Liberty.

Early life

Jackson was born in 1731. His mother, Mary, a widow, owned a general store located in Cornhill, MA in Boston named "The Brazen Head."[2] Jackson took after his mother; in 1758 the two were working side-by-side running the store.[2]

The Brazen Head

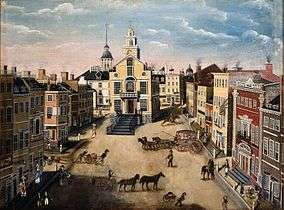

Originally owned by Mary Jackson, the Brazen Head was a general store located in Cornhill, an area in the heart of Boston. Located next to the Town House, otherwise known as the Old State House, the Brazen Head was most likely a well-known store. The Town House was an incredibly important building, and has been referred to as “The principle public building of the Provence [Massachusetts].”[3] According to History of the Old State House by George Moore, “Washington, Lafayette, Franklin, Jefferson” and others joined important Massachusetts residents in visiting the Town House.[3] It can be deduced, then, that the Brazen Head was an important and highly trafficked store due to its centrality within Boston and its location next to the Town House. A newspaper advertisement in a 1736 edition of the New England Weekly Journal also provided us with some insight on the Brazen Head’s surroundings. The advertisement stated, “Several sorts of glass bottles, as also goods velvet corks, to be sold by Mr. Belthazar Bayard, next door to Brazen Head in Cornhil, Boston.”[4] This indicates that the Brazen Head was not the only landmark in the area, and that Cornhill housed many different, important stores.

The Jacksons relied heavily on imported goods their entire lives, and before the non-importation agreement it seems like they were well respected in the Boston community. An advertisement in the Boston Gazette from 1759 stated, “Imported from London and Bristol, and sold by Mary Jackson and Son at the Brazen Head, Cornhill, Boston: Brass kettles, skillets, warming pans, iron pots and kettles, powder, [etc]… A wholesale customer may depend upon being well serv’d at a reasonable price.”[5] The Brazen Head clearly sold a diverse array of goods, and according to the ad, the Jacksons could be counted upon as trustworthy vendors.

The Great Boston Fire

The Brazen Head, and the entire city of Boston for that matter, suffered a major setback in 1760. “The Great Boston Fire” broke out on March 17 and 18.[6] It raged on for two days, destroyed 349 buildings and left over 1,000 people homeless.[6] According to a newspaper article in the Boston Evening Post, “[The fire] began about two o’clock in the morning, in the dwelling house of Mrs. Mary Jackson and Son, and the brazen head in Cornhill, but the accident which occasioned it is yet uncertain. The flames catch’d the houses adjoining in the front of the street, and burn four large buildings before a stop could be put to it there."[7] The fire was obviously devastating, but the Jacksons rebounded quickly. As seen in Jackson’s biography from the Massachusetts Historical Society, the shop was reopened in 1763, run now exclusively by William.[2]

Nonimportation agreement

In 1767, the merchants of Boston signed a nonimportation agreement in response to the Townshend Acts. The aim was to pressure Great Britain into withdrawing what they saw as punitive taxation legislation. Author Richard Archer described the committee that drew up this agreement, which included John Rowe, William Phillips, and John Hancock, as "a veritable who's who of Boston smugglers".[8] Most of the merchants did not expect the agreement to apply to existing stock, or that they could not sell British goods. They had just agreed not to import them. In April 1769 a committee was formed to enforce the nonimportation agreement.[9] This committee began to demand inspections of merchants' premises and forced them to put proscribed goods into storage.

Initially, the non-importation agreement created by Boston merchants was designed to have a definite time frame, specifically between January 1769 and December 1769.[10] The terms were agreed upon, and carried out rather successfully. Archer additionally wrote, “On May 2, after a report by the second committee, the body of merchants concluded that only six of the 211 signers of the Agreement had broken their word ‘through Inattention,’ by neglecting to countermand their orders placed in the fall.”[9] This can be seen through two different lenses; on one hand, the agreement was largely successful, but on the other hand, it showed that Jackson, while in the minority, was not the only one who continued to sell imported goods. In retrospect, it makes sense that Jackson imported British made goods. Larger businesses were able to continue profiting during this time period, but family owned stores such as the Brazen Head did not have the capital or domestic connections necessary to prosper without importing goods.[10] On top of this, it was agreed on that the period of nonimportation would continue past 1769 if necessary in an effort to strengthen the colonists’ stance against the British.[11]

Nonimportation was not exclusive to Boston, and those identified as importers were blacklisted all throughout New England. Jackson, for example, was listed in a newspaper located in New London, Connecticut in 1770. The newspaper printed a list of those who “audaciously” continued to import British goods, and singled out specific merchants as traitors to the revolutionary cause.[12] This shows the massive influence that the Sons of Liberty and the like had on the general population, and how much the organization’s propaganda affected the colonial population.

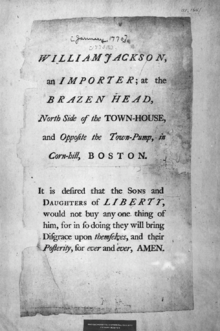

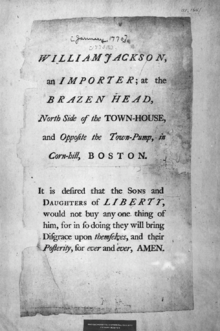

Broadside

Despite the clear economic strain that nonimportation was putting on Boston businesses, the Sons of Liberty wasted no time in shaming those who continued to import and sell British goods. After the May 2nd meeting cited earlier, the Sons of Liberty began publishing the names of storeowners who did not comply with the Non-Importation Agreement in Boston newspapers.[9] This gave not only the importers a bad name, but also the consumers who continued to buy goods from the blacklisted stores.

In the case of Jackson, the Sons of Liberty went even farther in their attack on the Brazen Head. They wrote and printed a broadside (a large, poster sized notice) condemning Jackson and the Brazen Head. It used passionate and charged language in its attempt to portray Jackson as a traitor. The broadside read, “WILLIAM JACKSON, an IMPORTER; at the BRAZEN HEAD, North Side of the TOWN-HOUSE, and Opposite the Town-Pump, [in] Corn-hill, BOSTON. It is desired that the SONS and DAUGHTERS of LIBERTY, would not buy any one thing of him, for in so doing they will bring disgrace upon themselves, and their Posterity, for ever and ever, AMEN.”

The broadside also inspired violence amongst protesters. In late 1769 or early 1770, the approximate time frame when the broadside was first posted, an angry mob surrounded the Brazen Head and other Boston stores whose owners failed to comply with nonimportation.[2] The mob created effigies in addition to the broadsides, and even attempted (but failed) to intentionally burn down Jackson’s store.[2] The intimidation and harassment Jackson was subject to by colonial patriots is an example of how brutally Loyalists in Boston were treated in the pre-revolutionary era. Boston, the epicenter of pre-war patriotism, proved to be a hostile environment for anyone who remained loyal to the crown.

Later life

After the Revolutionary War began, Jackson’s public profile significantly decreased. The damage caused by the Sons of Liberty had been severe, and as revolutionary sentiments got stronger, the contempt directed at Jackson only intensified. In 1776, Jackson and other Loyalist merchants fled Boston with a good portion of the British military in hopes of reaching England, but American privateers intercepted the small fleet before reaching its destination.[13] J.L. Bell, author of the brief article, "Escaping Tories: Captured at Sea," stated, “According to the 8 April Boston Gazette, William Jackson was the new owner of the ship Manly (the captain of American privateering fleet) had captured, a prize estimated to be worth £35,000 with the goods aboard."[13] Colonial authorities subsequently threw Jackson in jail, and the following year he was banished from Boston.[2]

Jackson had paid a dear price for loyalty; patriots used him as a symbol of a traitor, and destroyed his economic and personal lives. Not much is documented following his capture and arrest in 1776 as Jackson slowly faded out of Boston society. In 1777 he was put on trial for "attempting to profit from the distress caused by the Revolution" and exiled from Boston.[1] It is known that Jackson received little compensation or pension from the British in return for his unwavering support at the end of the war. Shortly after he was banished from Boston, Jackson ended up moving to England, where he died in 1810.[2]

References

- 1 2 Curwen, p. 696

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Sons and Daughters of Liberty Unite to Boycott William Jackson".

- 1 2 History of the Old State House. p. 4.

- ↑ "Advertisements". New England Weekly Journal. 1736.

- ↑ "Advertisements". Boston Gazette. 1759.

- 1 2 "Boston Fire". Elizabeth Murray Project.

- ↑ "Boston Fire". Boston Evening Post.

- ↑ Archer, p. 77

- 1 2 3 Archer, p. 146

- 1 2 Archer, p. 145

- ↑ Archer, p. 149

- ↑ New London Gazette, 1770

- 1 2 "Escaping Tories: Captured at Sea". Boston 1775.

Bibliography

- "Advertisements," Boston Gazette and Country Journal (Boston, MA), May 28, 1759. Retrieved from NewsBank InfoWeb

- Archer, Richard. As If an Enemys Country The British Occupation of Boston and the Origins of Revolution. New York, US: Oxford University Press, 2010. Accessed November 5, 2016. ProQuest ebrary.

- Bell, J. L. "Escaping Tories: Captured at Sea," Boston, 1775 (Blog). April 7, 2008.

- Boston Evening-Post, 24 March 1760, "Boston Fire," Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

- Cleary, Patricia and Elizabeth Murray. "Boston Fire," Elizabeth Murray Project. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2000.

- Curwen, Samuel. The Journal of Samuel Curwen, Loyalist, volume 1. Edited by Andrew Oliver. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972 OCLC 702323235.

- Green, T. and S. Kneeland. “Advertisements,” New England Weekly Journal (Boston, MA), Sept 7, 1736. Retrieved from NewsBank InfoWeb

- Moore, George. Notes on the History of The Old State House. Boston: Cupples, Upham & Co., 1886.

- New London Gazette (New London, CT), August 24, 1770. Retrieved from NewsBank InfoWeb

- "Sons and Daughters of Liberty Unite to Boycott William Jackson," Massachusetts Historical Society, August 2008. Accessed 15 November 2016.

- Sons Of Liberty. William Jackson, an importer; at the Brazen Head, North side of the Town-House, and opposite the Town-Pump, in Corn-Hill, Boston. It is desired that the sons and daughters of liberty, would not buy any one thing of him, for in so doing the will. Boston, 1770. Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. (Accessed November 15, 2016.)