Women in architecture

Women in architecture have been documented for many centuries, as professional (or amateur) practitioners, educators and clients. Since architecture became organized as a profession in 1857, the number of women in architecture has been low. At the end of the 19th century, starting in Finland, certain schools of architecture in Europe began to admit women to their programmes of study. In 1980 M. Rosaria Piomelli, born in Italy, became the first woman to hold a deanship of any school of architecture in the United States, as Dean of the City College of New York School of Architecture.[1] However, only in recent years have women begun to achieve wider recognition with several outstanding participants including two Pritzker prizewinners since the turn of the millennium. However, despite the fact that some 40% of architecture graduates in the western world are now women, not more than 12% are estimated to be practicing as licensed or registered architects.[2][3]

Early examples

Two European women stand out as early examples of women playing an important part in architecture, designing or defining the development of buildings under construction. In France, Katherine Briçonnet (ca. 1494–1526) was influential in designing the Château de Chenonceau in the Loire Valley, supervising the construction work between 1513 and 1521 and taking important architectural decisions while her husband was away fighting in the Italian wars.[4]

In Britain, there is evidence that Lady Elizabeth Wilbraham (1632–1705) studied the work of the Dutch architect Pieter Post as well as that of Palladio in Veneto, Italy, and the Stadtresidenz at Landshut, Germany.[5] She has been put forward as the architect of Wotton House in Buckinghamshire and of many other buildings. It has also been suggested that she tutored Sir Christopher Wren. Wilbraham had to use male architects to supervise the construction work.[6] There is now much research including that by John Millar [6]to show she may have designed up to 400 buildings including 18 London churches previously attributed to her pupil Sir Christopher Wren.

Towards the end of the 18th century, another Englishwoman, Mary Townley (1753–1839), tutored by the artist Sir Joshua Reynolds, designed several buildings in Ramsgate in south-eastern England including Townley House which is considered to be an architectural gem.[7] Sarah Losh (1785-1853) was an English woman and landowner of Wreay. She has been described as a lost Romantic genius, antiquarian, architect and visionary. Her main work is St Mary's Church (Wreay), Cumbria, but she also constructed various associated buildings and monuments.[8][9][10]

-

Katherine Briçonnet: Chenonceau tower (1521)

-

Wotton House, Buckinghamshire (1714), possibly designed by Elizabeth Wilbraham

-

Mary Townley: Townley House, Ramsgate (1780)

-

Sarah Losh: St Mary's Church, Wreay (1842)

Modern pioneers

Yet another Englishwoman, Sophy Gray (1814–1871), wife of Robert Gray who became bishop of Cape Town in 1847, proved to be a competent assistant, not only helping her husband with his administrative and social obligations but above all by designing at least 35 of the South African Anglican churches completed between 1848 and 1880, all in the Gothic Revival style in which she showed strong interest.[11]

The daughter of a French-Canadian carriage maker, Mother Joseph Pariseau (1823–1902) was not just one of the very earliest female architects in North America but a pioneer in the architecture of the north-western United States. In 1856, together with four sisters from Montreal, she moved to Vancouver, Washington where she designed eleven hospitals, seven academies, five schools for Native American children, and two orphanages in an area encompassing today's Washington State, northern Oregon, Idaho, and Montana.[12]

Louise Blanchard Bethune (1856–1913) from Waterloo, New York, was the first American woman known to have worked as a professional architect. In 1876, she took a job working as a draftsman in the office of Richard A. Waite and F.W. Caulkings in Buffalo, New York where she worked for five years, demonstrating she could hold her own in what was a masculine profession. In 1881, she opened an independent office partnered with her husband Robert Bethune in Buffalo, earning herself the title as the nation's first professional woman architect.[13] She was named the first female associate of the American Institute of Architects (A.I.A.) in 1888 and in 1889, she became its first female fellow.[14][15]

Another early practicing architect in the United States was Emily Williams (1869–1942) from northern California. In 1901, together with her friend Lillian Palmer, she moved to San Francisco where she studied drafting at the California High School of Mechanical Arts. Encouraged by Palmer, she went on to build a number of cottages and houses in the area, including a family home on 1037 Broadway in San Francisco, now a listed building.[16]

Theodate Pope Riddle (1868–1946) grew up in a well-to-do background in Farmington, Connecticut, where she hired faculty members to tutor her in architecture. Her early designs, such as that for Hill-Stead (1901), were translated into working drawings by the firm of McKim, Mead and White, providing her with an apprenticeship in architecture. She was the first woman to become a licensed architect in both New York and Connecticut and in 1926 was appointed to the AIA College of Fellows.[17]

A notable pioneer of the early days was Josephine Wright Chapman (1867–1943). Chapman received no formal education in architecture but went on design a number of buildings before setting up her own firm. The architect of Tuckerman Hall in Worcester, Massachusetts, she is considered to be one of America's earliest and most successful female architects.[18]

Romanian architect Virginia Andreescu Haret (1894–1962), first woman to graduate with a degree in architecture in 1919 and first woman as Romanian Architectural Inspector General. She continued her studies in Italy. She worked at the Technical Service of the Ministry of Education, for which reason she did numerous and important projects [19] for schools, in Bucharest (Şincai and Cantemir Lyceum) as well as in the country (Bârlad, Focşani). Side by side with buildings of large dimensions, she also designed houses for one or two persons. The mobility did not stop at the studies in Italy, she was present also at numerous congresses of architecture in Rome, Paris, Moscow, Bruxelles ...

A highly influential player was Mary Colter (1869–1958). After studying at the California School of Design in San Francisco, she was employed by the Fred Harvey Company, first for interior design but soon to take on ambitious architectural projects, including landmark hotels and Rustic lodges in the Southwest, several in Grand Canyon National Park. She often used Native American motifs (and artisans) while blending the regional Spanish Colonial Revival Style and Pueblo Revival Style,[20] but she also was fluent in Art Deco and even Streamline Moderne.

-

Sophy Gray: St Mark's Cathedral, George, South Africa (1849)

-

Mother Joseph Pariseau: Providence Academy, Vancouver, Washington (1873)

-

Josephine Wright Chapman, Tuckerman Hall, Worcester, Massachusetts (1902)

-

Mary Colter: La Posada Hotel, Winslow, Arizona (1930)

First academic qualifications

Finland

Finland is the country in which women were first permitted to undertake architectural studies and receive academic qualifications[21] even if they were initially given the status of special students. The earliest record belongs to Signe Hornborg (1862–1916) who attended the Helsinki Polytechnic Institute from the spring of 1888, graduating as an architect in 1890 "by special permission". She does not, however, appear to have acted as an independent architect.[22] Other graduates in architecture at the Polytechnic Institute in the 1880s include Inez Holming, Signe Lager Borg, Bertha Stollenwald, Stina Östman and Wivi Lönn.[23] Lönn (1872–1966), who attended the institute from 1893 to 1896, has the honour of being the first woman to work independently as an architect in Finland. On graduating, she immediately established her own architectural firm. Together with Armas Lindgren she designed the New Student House in Helsinki (1910) and the Estonia Theatre in Tallinn (1913) before designing a wide variety of buildings herself. One of her last was the Sodankylä Geophysical Observatory, completed in 1956.[24] Hilda Hongell (1867–1952), from Finland's Åland Islands, became a special student at Helsinki Industrial School in 1891 at a time when only men could attend the institution. Following excellent results, she was accepted as a regular student the following year, and began her career in architecture in 1894. She went on to design 98 buildings in the Mariehamn district of the Åland Islands, mostly town houses and farm houses in the ornamental Swiss style. Like Wivi Lönn, she is sometimes referred to as the first female architect in Finland.[25]

-

Hilda Hongell: Wooden villa in Mariehamn, Finland (1987)

Other early graduates

Fay Kellogg (1871–1918) learnt her architectural skills with a German tutor who taught her drafting, at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, and by working with Marcel de Monclos in his Paris atelier. She had hoped to study at the École des Beaux-Arts but as a woman was refused admission. As a result of her efforts, however, the institution later opened its doors to women wishing to study architecture. On her return to the United States, Kellogg helped design the Hall of Records in Lower Manhattan before opening a studio of her own. She went on to design hundreds of buildings in the New York area, encouraging the New York Times to describe her as "one of the most successful woman architects in America".[26] Julia Morgan (1872–1957) was more successful as she was the first woman to receive a degree in architecture from the École des Beaux-Arts. She was initially refused admission as a woman in 1896 but reapplied and was successfully admitted in 1898. After graduating in 1901, she returned to California where she had a prolific and innovative career, blazing new paths professionally, stylistically, structurally, and aeshetically, setting high standards of excellence in the profession. Completing over 700 projects, she is especially known for her work for women's organizations and key clients, including Hearst Castle in San Simeon, considered to be one of her masterpieces.[27] She was the first woman architect licensed in California. Mary Rockwell Hook (1877–1978) from Kansas also traveled to study architecture at the École des Beaux-Arts where she suffered from discrimination against women after sitting for examinations. She was not successful in gaining admittance, and returned to America in 1906, where she did practice architecture. She designed the Pine Mountain Settlement School in Kentucky as well as a number of buildings in Kansas City where she was the first architect to incorporate the natural terrain into her designs and the first to use cast-in-place concrete walls.[28]

Florence Mary Taylor (1879–1969) emigrated at an early age from England to Australia with her parents. She enrolled in night classes at the Sydney Technical College where she became the first woman to complete final year studies in architecture in 1904.[29] She went on to work in the busy office of John Burcham Clamp, where she became chief draftsperson.[30] In 1907, with Clamp's support, she applied to become the first female member of the Institute of Architects of New South Wales but faced considerable opposition, only being invited to join in 1920.[31]

Isabel Roberts (1871–1955), born in Missouri, studied architecture in New York City at the Masqueray-Chambers Atelier, established by Emmanuel Louis Masqueray along the lines of the French École des Beaux-Arts. It was the first studio in the United States specifically established to teach the practice of architecture.[32] Convinced of the abilities of women as architects. Masqueray was keen to include them among his students. Roberts became a member of Frank Lloyd Wright's design team before partnering with Ida Annah Ryan (1873–1950), in Orlando, Florida. Ryan was the first woman to earn a master's degree in architecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology[33] although Sophia Hayden Bennett (1868–1953) had graduated in architecture there in 1890.[34]

-

Julia Morgan: Hearst Castle, San Simeon, California (1919–1947)

Esther Marjorie Hill was the first woman to graduate from a Canadian architecture school, in 1920.

European developments

After Finland, several other European countries allowed women to study architecture. In Norway, the first female architect was Lilla Hansen (1872–1962) who studied at the Royal Drafting School (Den Kongelige Tegneskole) in Kristiania (1894) and served architectural apprenticeships in Brussels, Kristiania and Copenhagen. She established her own practice in 1912 and gained immediate success with Heftyeterrassen, a Neo-baroque residential complex in Oslo. She went on to design a number of large villas as well as student accommodation for women.[35]

The first woman to run an architecture practice in Germany was Emilie Winkelmann (1875−1951). She studied architecture as a guest student registered as Student Emil at the College of Technology in Hanover (1902–1908) but was refused a diploma as women were not entitled to the qualification until 1909. Working from her practice in Berlin where she employed a staff of 15, she completed some 30 villas before the outbreak of war. One of her most notable buildings is the Tribüne theatre in Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf, originally a girls school.[36]

In Serbia, Jelisaveta Načić (1878–1955) studied architecture at the University of Belgrade at a time when it was felt that women should not enter the profession. At the age of 22, she was the first woman to graduate from the Faculty of Engineering. As a woman, she was unable to obtain the ministerial post she sought but gained employment with the Municipality of Belgrade where she became chief architect. Among her notable achievements are the well-proportioned Kralj Petar I (King Peter I) elementary school (1906) and the Moravian-styled Alexander Nevsky Church (1929), both in Belgrade.[37] The first female architect in Serbia, she did much to inspire other women to enter the profession.[38]

Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky (1897–2000) was the first female architect in Austria and the first woman to graduate from Vienna's Kunstgewerbeschule, though she was admitted only after a letter of recommendation from an influential friend. A pioneer of social housing development in Vienna and Frankfurt, she combined design with functionality, especially in her Frankfurt Kitchen, the prototype of today's built-in kitchen.[39]

In Switzerland, Flora Steiger-Crawford (1899–1991) was the first woman to graduate in architecture from Zurich's Federal Institute of Technology in 1923. She established her own firm with her husband Rudolf Steiger in 1924.[40] Their first project, the Sandreuter House in Riehen (1924), is considered to be the first Modernist house in Switzerland. In 1938, she terminated her architectural activities in favour of sculpture.[41]

-

Lilla Hansen: Heftyeterrassen, Oslo (1929)

-

Emilie Winkelmann: Tribüne theatre, Berlin (1915)

-

Jelisaveta Načić: Alexander Nevsky Church, Belgrade (1929)

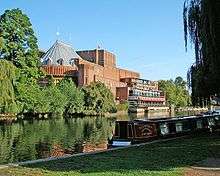

The first woman to be admitted to Britain's Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) was Ethel Charles (1871–1962) in 1898. She and her sister Bessie were both trained as architects under the partnership of Ernest George and Harold Peto. In 1893, they both attempted to continue their training by attending the Architectural Association School of Architecture but were refused entry. Ethel completed part of the course offered by the Bartlett School of Architecture, receiving distinctions. As a woman, though, she was unable to obtain large-scale commissions and was forced to concentrate on modest housing projects such as labourers' cottages.[42][43] Another early female architect in Britain was Edith Hughes (1888–1971), a Scot, who after attending lectures on art and architecture at the Sorbonne, studied at Gray's School of Art, Aberdeen, where she received a diploma in architecture in 1914. In addition to teaching at the Glasgow School of Art, she established her own practice in 1920, specializing in kitchen design.[44] The first women to design a major building in Britain was Elisabeth Scott (1898–1972) who was the architect behind the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre at Stratford-upon-Avon completed in 1932.[45]

-

Edith Hughes: Glasgow Mercat Cross (left) (1930)

Male and female professional partnerships

A number of the more important women architects in the first half of the 20th century partnered with men, often forming husband-and-wife practices.[46] Such partnerships began in the early years of women's involvement when some of the most successful male architects worked with women. Since the 1960s, which saw increased enrollment by women into schools of Architecture, male and female students have often met and later married; long hours working together and a shared passion have been described as "the perfect prescription for romance".[47] A good overview of this topic is also discussed in Ann Forsyth's "In Praise of Zaha" [48]

Male-female partnerships in architecture sometimes lead to misattribution of the work to the male partner, often because the male is better known. This can be seen as the result of an underlying discrimination or biased attitude. What has been described as the "tradition of misattribution" has remained a "secret" until recent years.[49]

Some particularly notable male-female partnerships in architecture include:

- Aino Aalto (1894-1949) and Alvar Aalto - after qualifying as an architect in Finland in 1920, she married Alvar Aalto in 1923 and participated in the design of his earlier buildings, often contributing to the interiors as in the Villa Mairea (1937) in Noormarkku.[50]

- Reima and Raili Pietilä, another Finnish couple, worked closely together developing their early Modernistic style. Raili Pietilä (born 1926) found two the perfect number for a design team, explaining: "We often took our work with us: for a walk, in the kitchen, and in the evenings. And when doing competitions we used to take trips, like long train journeys, because we found that changing your environment affects your thinking."[51]

- In Denmark, Inger and Johannes Exner who married in 1952 formed a close, highly successful partnership, building or restoring churches, frequently exerting a functional as well as an aesthetic approach in their work.[52]

- French architect and designer Charlotte Perriand (1903–1999) established a partnership with an icon of modern architecture, Le Corbusier, contributing to the development of functional living spaces, especially by designing interiors and furniture for his buildings. She later recalled how Le Corbusier insisted on strict adherence to his demanding principles: "The smallest pencil stroke had to have a point, to fulfil a need, or respond to a gesture or posture, and to be achieved at mass-production prices." After collaborating with Le Corbusier for about ten years, Perriand left his studio in 1937 to concentrate on furniture design, often working with Jean Prouvé.[53] The Portuguese architect Maria José Marques da Silva (1914–1996) partnered with her husband David Moreira, completing a number of key buildings in the city of Porto.[54]

- In Germany, Elisabeth Böhm (born 1921) frequently worked with her husband, Gottfried Böhm, designing interiors for apartment buildings and other housing developments.[55]

- Margot Schürrmann (1924–1999) formed a lifelong partnership with her husband Joachim Schürmann. Their influence on German architecture was recognized by the Bund Deutscher Architeken who awarded them their Grand Prize 1998.[56]

- Maria Schwarz (born 1921) is remembered for her partnership with Rudolf Schwarz who assisted in reconstructing the city of Cologne, especially its churches, after the Second World War. After her husband's death in 1961, Maria continued to run the family firm, completing many of her husband's projects in the Cologne area.[55]

- Bernice Alexandra "Ray" Eames, furniture and interior designer, architect, artist, wife and partner of architect Charles Eames. Charles and Ray Eames designed the Eames House and other significant mid-20th century modern buildings. As well, the Eames' produced the influential Eames Lounge Chair and other modernist furniture.

- Elizabeth Close (1912–2011) had difficulty in finding employment after graduation until she followed fellow student William Close to Minneapolis. As husband and wife, they set up their own firm in 1938. In addition to designs of her own including many streamlined private homes, it was Elizabeth who ran the firm in her husband's absence during the Second World War and while he was busy constructing the University of Minnesota campus. The architectural historian Jane King Hession remarked: "By her example she inspired many women in architecture, myself included, but she didn't want to be known as a woman architect — just as an architect who happened to be a woman."[57]

- Marion Griffin (1871–1961) from Chicago, was the first employee hired by Frank Lloyd Wright.[58] Although Wright did not give her much recognition for her Prairie School designs, it now appears she not only contributed substantially to his studio's residential work but also did much to promote his ideas.[59] In 1911, Marion married Walter Burley Griffin, with whom she had worked in Wright's studio. Together they set up a highly successful partnership working first in the Chicago area on a variety of projects, then in Australia on the urban planning of Canberra, and finally in India until Griffin's death in 1937.[60] In her memoir, Mahony describes how she was indissolubly fused with her husband, emphasizing how together they championed various causes such as a library for the Indian city of Lucknow or Castlecrag, a community near Sydney that they designed.[61]

- Also in Australia, Mary Turner Shaw (1906-1990) had found it difficult to complete her architecture studies at the University of Melbourne, and instead became an architect via articled studentship. She worked for various architectural firms in Australia (1931-1936) and the UK (1937), and traveled Europe meeting many key Modernist architects. After working for others again in Australia (1938), she formed an architectural firm, Romberg & Shaw, with the Modernist architect Frederick Romberg. The firm operated from 1939 to 1942. During that period they produced "some of the most celebrated blocks of flats in Australia",[62] including the Yarrabee Flats, South Yarra, Victoria(1940) and the Newburn Flats, South Melbourne, Victoriain 1939. Shaw continued to practice architecture until her retirement in 1969.

- Denise Scott Brown (born 1931) and Robert Venturi met at the University of Pennsylvania in 1960. Shortly after their marriage in 1967, Scott Brown joined his Philadelphia firm Venturi and Rauch, where she became principal in charge of planning in 1969. She has since played a major role at the firm (renamed Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates in 1989) leading civic planning projects and studies, and collaborating with Venturi on the firm's larger projects. She is however resentful of the fact that she is seldom credited for her work. For example, it was her husband who was awarded the Pritzker Prize in 1991 although she explains: "We both design every inch of a building together." In 1997 she speculated: "The question of being a woman will be in the air for ever in my case. If I had not married Bob, would I have gone further or not? Who can tell? But the same question holds for him. If he had not married me, would he have gone further?"[46] Denise Scott Brown also disclosed her feelings about this situation in a chapter of "Gender Space Architecture".[63]

- In the UK, architect Amanda Levete (born 1955) became a director of Future Systems with her husband Jan Kaplický. In 1999 they won the Royal Institute of British Architects' (RIBA) Stirling Prize for their Media Centre at Lords Cricket Ground.[64] Because Kaplický neither knew or cared about cricket, Levete chose to attend the meetings with the client. Levete is credited with the ability of making Future Systems' organic forms marketable.[65]

- Ivenue Love-Stanley and her husband William J. "Bill" Stanley III co-founded their architectural firm in 1983 after they had each (in different years) become the first African-Americans, first youngest male then first female, to be registered architects in the U.S. South. Love-Stanley is the business manager and principal in charge of production while her husband handles marketing and is in charge of design.[66]

Progress since 2000

Several women architects have had considerable success in recent years, gaining wide recognition for their achievements:

In 2004, the Iraqi-British architect Zaha Hadid became the first woman to be awarded the Pritzker Prize.[67] Among her many projects, special mention was made of the Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati and the BMW Central Building in Leipzig. When awarding the prize, the chairman of the jury, spoke of her "unswerving commitment to modernism" explaining how she had moved away from existing typology, from high-tech, shifting the geometry of buildings."[68] Since 2004, she has completed many other notable works including the Guangzhou Opera House in Guangzhou, China, and the London Aquatics Centre for the 2012 Summer Olympics.[69][70]

In 2010, another woman became a Pritzker Prize winner, Kazuyo Sejima from Japan, in partnership with Ryue Nishizawa. Lord Palumbo, the jury chairman, spoke of their architecture "that is simultaneously delicate and powerful, precise and fluid, ingenious but not overly or overtly clever; for the creation of buildings that successfully interact with their contexts and the activities they contain, creating a sense of fullness and experiential richness." Special consideration had been given to the Glass Center at the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio, and the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa in Ishikawa, Japan.[71]

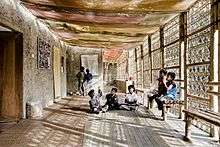

In 2007 Anna Heringer (born 1977, Germany) won the Aga Khan Award for Architecture for her METI Handmade School built with bamboo and other local materials in Rudrapur, Bangladesh. An example of sustainable architecture, the project was praised not only for its simple, humane approach and beauty but also for the level of cooperation achieved between architects, craftsmen, clients and users.[72] Several RIBA European Awards have been won in recent years by the Danish firm Lundgaard & Tranberg where Lene Tranberg (born 1956) has been a key architect. Projects have included the Royal Danish Playhouse (2008) and Tietgenkollegiet (2005).[73]

In 2010, Sheila Sri Prakash was the first Indian Architect invited to serve on the World Economic Forum's Design Innovation Council, where she created the Reciprocal Design Index as a design tool for Holistically Sustainable Development. She is the first woman in India to have established her in own firm. In 1992, she was a pioneer of environmentally sustainable architecture and had designed a home with recycled material[74]

In 2013, Women In Design, a student organization at the Harvard Graduate School of Design started a petition for the Pritzker Architecture Prize to recognize Denise Scott Brown who was not awarded in 1991, while her partner, Robert Venturi was.[75] Also in 2013 Julia Morgan became the first woman to receive the AIA Gold Medal, which she received posthumously.[76] In 2014 the Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre, designed by Zaha Hadid, won the Design Museum Design of the Year Award, making her the first woman to win the top prize in that competition.[67] In 2015 Hadid became the first woman to be awarded the RIBA Gold Medal in her own right.[67]

In 2014 Parlour: women, equity, architecture published the Parlour Guides to Equitable Practice, which provide a practical resource for moving toward a more equitable profession, with a focus on gender equity.[77]

-

Kazuyo Sejima: Christian Dior Omotesando Building, Tokyo (2003)

-

Anna Heringer: METI Handmade School, Bangladesh (2005)

-

Lene Tranberg: Tietgen Student Housing, Copenhagen (2006)

-

Jeanne Gang: Aqua, Chicago (2009)

Women's influence

Although until recently their contributions have been largely unnoticed, women have in fact exerted a fair amount of influence on architecture over the past century. It was Susan Lawrence Dana, heiress to a mining fortune, who in 1902 chose to have her house in Springfield, Illinois, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright, so ensuring his breakthrough. Women have also played a key role in historic preservation through organizations such as the Daughters of the American Revolution (1890).[78] In 1985, Bulgarian architect Milka Bliznakov founded the International Archive of Women in Architecture to expand the availability of research materials concerning women in architecture.[79] Recent studies also show that from the 1980s, women, as housewives and consumers, were instrumental in bringing new approaches to design, especially interiors, achieving a shift from architecture to space.[80]

A study on experience in Canada highlights the widespread contributions women have made in recent years, developing innovative approaches to practice and design. Women's significant and growing presence in the profession has attracted more attention than issues of marginalization.[81]

Exhibitions presenting women's achievements in various fields provided early opportunities for women demonstrate their competence in designing pavilions. They included the 1893 exhibition in Chicago, where the women's pavilion was designed by Sophia Hayden, and two in 1914 in Germany: the Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne, whose Haus der Frau was designed by Lilly Reich, and the Burga Expo in Leipzig devoted to books and graphic art. Inspired by these successes, in 1928 Lux Guyer from Switzerland designed pavilions for SAFFA (Schweizerische Ausstellung für Frauenarbeit) a fair exhibiting the accomplishments of women first held in Bern. The second SAFFA, held in Zurich in 1958, was put together by a team of 28 female architects, establishing architecture as a profession open to women in Switzerland.[82]

Recent statistics

It is not easy to find reliable statistics on women's place in architecture across the world. Much of the information is dated and some is based on surveys inviting responses but with no guarantee of comprehensive coverage. As noted far above, in 2012 it was estimated that while about 40% of architecture graduates in the western world were women, only about 12% were estimated to be practicing as licensed or registered architects.[2]

- Europe

In 2010, a survey conducted by the Architects' Council of Europe in 33 countries, found that there were 524,000 architects, of whom 31% were women. However the proportions differed widely from country to country. The countries with the highest proportion of female architects were Greece (57%), Croatia (56%), Bulgaria (50%), Slovenia (50%) and Sweden (49%) while those with the lowest were Slovakia (15%), Austria (16%), the Netherlands (19%), Germany (21%) and Belgium (24%). Over 200,000 of Europe's architects are in Italy or Germany where the proportions of women are 30% and 21% respectively.[83]

- Australia

A study conducted in Australia in 2002 indicated that women comprise 43% of architecture students while their representation in the profession varied from 11.6% in Queensland to 18.2% in Victoria. More recent Australian data, collected and analyzed as part of the Equity and Diversity in the Australian Architecture Profession research project, shows that whatever measure used women continue to disappear from the profession.[84] Women have comprised over 40% of Australian architecture graduates for over two decades, but are only 20% of registered architects in Australia.[85][86][87][88]

- United Kingdom

A United Kingdom survey in 2000 stated that 13% of practising students were women although women comprised 38% of students and 22% of teaching staff.[89] Data from the Fees Bureau in November 2010 showed, however, that only 19% of professional architects were women, a drop of 5% since 2008.[90]

- United States

In the United States, the National Architectural Accrediting Board reported in 2009 that 41% of architecture graduates were women while the AIA National Associates Committee Report from 2004 gives the percentage of licensed female architects as 20%. In 2003, an AIA Women in Architecture study found that women accounted for 27% of staff in U.S. architecture firms.[91] The honorific FAIA was held by 174 women and 2,199 men, or roughly 8% in 2005.[92]

See also

References

- ↑ "rosaria_piomelli". Digital-archives.ccny.cuny.edu. 1937-10-24. Retrieved 2015-09-29.

- 1 2 Garry Stevens. "Women in Architecture". archsoc.com. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- ↑ Suzanne Stephens, "Not Only Zaha. What is it like to be a female architect with a solely owned firm in the U.S. today?", Architectural Record, December 2006. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ↑ M. E. Aubry-Vitet, "Chenonceau", in Revue des deux mondes, no 69 (1867), p.855. (French)

- ↑ John Millar The first woman architect, The Architects' Journal, 11 November 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- 1 2 Jay Merrick Elizabeth Wilbraham, the first lady of architecture, The Independent, 16 February 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ Paul Nettleingham, "Townley House in Ramsgate", Michaels Bookshop Ramsgate. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ St Mary's Church Wreay (Accessed Sept 2012)

- ↑ Uglow, Jenny (2012) The Pinecone, Faber and Faber

- ↑ Bullen, J. B. (2001) Sara Losh: Architect, Romantic, Mythologist The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 143, No. 1184, Nov., pp. 676-684

- ↑ "Gray, Sophia (Sophie) Wharton Myddleton", ArteFacts. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "Mother Joseph", Architect of the Capitol. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "Louise Blanchard Bethune (1856-1913)", Women in Architecture (University of Illinois). Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ Louise Blanchard Bethune (1856-1913, Women in Architecture (University of Illinois ). Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ Maureen Meister (4 November 2014). Arts and Crafts Architecture: History and Heritage in New England. University Press of New England. pp. 235–. ISBN 978-1-61168-664-7.

- ↑ Inge S. Horton, "Emily Williams: San Jose's First Woman Architect", Women Architects in Northern California, first published in Newsletter of PAC San Jose, Vol.17, No.4. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "Women in Architecture", ARVHA. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ "Josephine Wright Chapman and Tuckerman Hall", Tuckermanhall.org. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ "Review of European Studies; Vol. 5, No. 5; 2013 ISSN 1918-7173 E-ISSN 1918-7181 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education" Virginia Haret. published November 18, 2013.

- ↑ A. J. Hewat, "Mary Colter: Architect of the Southwest", The Wilson Quarterly. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ Päivi Nikkanen-Kalt, "Female architects in Finland", ARVHA. Retrieved 23 April 2012

- ↑ Karl Heinz Hoffmann and Anika Hakl, "Frauen und Häuser", Hamburgisches Architekturarchiv der Hamburgischen Architektenkammer. (German) Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ "Perustaminen: Nainen arkkitehtina", Architecta. (Finnish) Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ "Lönn, Wivi (1872 - 1966)", Biografiakeskus. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ "Hilda Hongell", Mariehamns stad. (Swedish) Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "Woman Invades Field of Modern Architecture", The New York Times, November 17, 1907. Retrieved 17 April 2012

- ↑ "Julia Morgan, Early Architect, 1872-1957", California State Capitol Museum. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ "Mary Rockwell Hook", International Archive of Women in Architecture. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ Willis, Julie and Bronwyn Hanna, Women Architects in Australia 1900-1960, Royal Australian Institute of Architects, 2000

- ↑ Hanna, Bronwyn Hanna "Absence and Presence, A Historiography of Early Women Architects in New South Wales", PhD, University of New South Wales, 1999. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ Ludlow, Christa (1990). "Taylor, Florence Mary (1879 - 1969)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. Retrieved 2007-09-07.

- ↑ "Noted Architect Dead. E. L. Masqueray Was Chief of Design of St. Louis Exposition", New York Times, May 27, 1917. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ Joy Wallace Dickinson, "Roberts brought Wright style to region's landmark buildings", Orlando Sentinel, September 11, 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ "Sophia Hayden Bennett", Mit.edu. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ "Lilla Hansen", Store Norske Leksikon. (Norwegian) Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ "Emilie Winkelmann, Architektin", Lexikon: Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf von A bis Z, Berlin.de. (German) Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ "Alexander Nevsky Church in Belgrade", Nothing Against Serbia. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ "One su bile prve: Jelisaveta Načić, prva žena u državnoj službi Srbije", Kulturni centar Beograda. (Serbian). Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ "Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, Biographie", k-faktor.com. (German) Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- ↑ "Rudolf Steiger", Sammlungen Aarchive, Zürcher Hochschule der Künste

- ↑ "Steiger-Crawford, Flora", Dictionnaire historique de la Suisse. (French) Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ Sumita Sinha, "Diversity in Architectural Education: Teaching and learning in the context of Diversity", Women in Architecture. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ Lynne Walker, "Golden Age or False Dawn? Women Architects in the Early 20th century", English-heritage.org. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ "Edith Mary Wardlaw Burnet Hughes (née Burnet)", Dictionary of Scottish Architects. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ Richardson, Albert (22 April 1932; quoted in Walker (1999: 257)). "Shakespeare Memorial Theatre". The Builder. 142: 718. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - 1 2 Kathryn H. Anthony, "Designing for Diversity: Gender, Race, and Ethnicity in the Architectural Profession", University of Illinois Press (2001), p. 56 et seq., ISBN 0-252-02641-1 (online here ).

- ↑ Anthony, p. 56.

- ↑ "In Praise of Zaha - FORSYTH - 2006 - Journal of Architectural Education - Wiley Online Library". Onlinelibrary.wiley.com. 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2015-09-24.

- ↑ Anthony, p. 56-57.

- ↑ "Internet exhibition on Alvar Aaltos Villa Mairea", Alvar Aalto. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ David Sokol, "Breaking the Modernist Mold: Raili Pietilä reflects on a life of design with her husband, Reima, and the new exhibition that examines the Pietilä legacy", Metropolismag.com, 24 April 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "Inger Exner", Dansk Kvindebiografisk Leksikon. (Danish) Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ "Charlotte Perriand, Architect + Furniture Designer (1903-1999)", Design Museum. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "Maria José Marques da Silva", University of Porto Famous Alumni. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- 1 2 "Die Frau an seiner Seite. Verleihung der AIV-Ehrenplaketten in Köln", Baunetz. (German) Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "Großer BDA-Preis", BDA. (German) Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "Then and Now: 'Old Gray Heads,' part two -- Elizabeth Close", University of Minnesota Press. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ Paul Kruty, Walter Burley Griffin, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- ↑ Lynn Becker, "Frank Lloyd Wright's Right-Hand Woman", Repeat. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "Beyond architecture: Marion Mahony and Walter Burley Griffin", Power House Museum. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ Fred A. Bernstein, "Rediscovering a Heroine of Chicago Architecture", New York Times, January 1, 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ Willis, J. 2012 "Shaw, Mary Turner" in P.Goad and J.Willis "The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture, Cambridge University Press, New York, p.624

- ↑ Rendell, Jane; Penner, Barbara; Borden, Iain (2000-01-01). Gender space architecture an interdisciplinary introduction. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 229, 263. ISBN 9780203449127.

- ↑ Stuart Jeffries, "The Saturday interview: architect Amanda Levete", The Guardian (London), April 9, 2011. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ Grice, E. "My greatest regret is that I didn't make peace with him in life", The Daily Telegraph, 11 March 2009. Retrieved 2012-04-23.

- ↑ "Architecture graduates Bill Stanley and Ivenue Love-Stanley are building marriage and monuments together". First Impressions. Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine. Retrieved 26 December 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Dame Zaha Hadid awarded the Riba Gold Medal for architecture - BBC News". Bbc.com. Retrieved 2015-09-24.

- ↑ "Announcement: Zaha Hadid Becomes the First Woman to Receive the Pritzker Architecture Prize", The Pritzker Architecture Prize. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ Jonathan Glancey and Dan Chung, "Zaha Hadid's Guangzhou Opera House – in pictures", The Guardian, 1 March 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ "London Aquatics Centre", Zha Hadid Architects. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ "Announcement: Architectural Partners in Japan Become the 2010 Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureates", The Pritzker Architecture Prize. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ↑ "Nine projects receive 2007 Aga Khan Award for Architecture", Aga Khan Development Network. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ↑ "Lene Tranberg", KVINFO. (Danish) Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ↑ "Recycled Materials in a Designer Home". Inside Outside. 10 June 1992.

- ↑ "Partner Without the Prize". The New York Times. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ↑ Wendy Moonan: "AIA Awards 2014 Gold Medal to Julia Morgan", in the Architectural Record, 16 December 2013

- ↑ "Parlour Guides to Equitable Practice - Parlour". archiparlour.org. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- ↑ Kathryn H. Anthony in Helen Tierney (ed.), Women's Studies Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999, pp. 104–108. Online here . ISBN 9780313296208.

- ↑ Sokolina, Anna (Summer 2011). "In Memoriam: Milka Bliznakov, 1927–2010". Slavic Review. 70 (2): 498–499.

- ↑ Brenda Martin, Penny Sparke: Women's Places: Architecture and Design 1860–1960. Routledge, 2003. pp. xiv–xv. ISBN 9780415284493

- ↑ Annmarie Adams, Peta Tancred. Designing Women: Gender and the Architectural Profession, University of Toronto Press, 2000,, pp. 3–5. ISBN 9780802082190.

- ↑ Évelyne Lang, "Les Premières Femmes Architectes de Suisse", École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne. (French) Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ↑ "The Architectural Profession in Europe 2010", Architects' Council of Europe. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ↑ "Research - Parlour". archiparlour.org. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- ↑ Matthewson, Gill; Clark, Justine. "The 'half-life' of women architects - Parlour". archiparlour.org. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- ↑ Matthewson, Gill. "Updating the numbers, part 1: at school - Parlour". archiparlour.org. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- ↑ Matthewson, Gill. "Updating the numbers, part 2: at work - Parlour". archiparlour.org. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- ↑ Matthewson, Gill. "Updating the numbers, part 3: Institute membership - Parlour". archiparlour.org. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- ↑ Karen Burns, "Women in architecture", ArchitectureAU. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ↑ Chrissi McCarthy, "Alarm as number of women architects falls for first time in nearly a decade", Constructing Equality, 11 November 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ↑ Alexis Gregory, "Calling All Women: Finding the Forgotten Architect", AIArchitect, November 12, 2009. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ↑ Kaplan, Victoria (2006). Structural inequality : black architects in the United States. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 26. ISBN 0742545830.

Further reading

- Adams, Annmarie; Tancred, Peta . Designing Women: Gender and the Architectural Profession. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0802044174

- Allaback, Sarah. The First American Women Architects. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0252033216

- Anscombe, Isabelle, A Woman's Touch: Women in Design from 1860 to the Present Day, Penguin, New York, 1985. ISBN 0-670-77825-7.

- Anthony, Kathryn H. Designing for Diversity: Gender, Race, and Ethnicity in the Architectural Profession, University of Illinois Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0252026416.

- Berkeley, Ellen Perry; McQuaid, Matilda (eds.): Architecture: A Place for Women, Washington D.C., 1989. ISBN 9780874742312.

- Durning, Louise, and Richard Wrigley, eds. Gender and Architecture. Chichester: Wiley, 2000. ISBN 0471985325.

- Griffin, Marion Mahoney, The Magic of America: Electronic Edition, Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, 2007.

- Lewis, Anna M., Women of Steel and Stone: 22 Inspirational Architects, Engineers, and Landscape Designers. Chicago Review Press, 2014. ISBN 978-1613745083.

- Lorenz, Clare.Women in Architecture: A Contemporary Perspective. New York: Rizzoli, 1990. ISBN 978-0847812776

- Martin, Brenda; Sparke, Penny: Women's Places: Architecture and Design 1860–1960. Routledge, 2003. ISBN 9780415284493

- Pollock, Griselda, Generations and Geographies in the Visual Arts, Routledge, London, 1996. ISBN 0-415-14128-1

- Tierney, Helen (ed.), Women's Studies Encyclopedia, Vol. 1, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999, pp. 104–108. Online here . ISBN 9780313296208.

- Torre, Susanna (ed.), Women in American Architecture: A Historic and Contemporary Perspective, A Publication and Exhibition Organized by the Architectural League of New York, New York, 1977

- Weisman, Leslie Kanes. Discrimination by Design. A Feminist Critique of the Man-Made Environment, University of Illinois Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0252063992